A Small Scottish Chest. Aidan Harrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha District Gazetteers Nabarangpur

ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR DR. TARADATT, IAS CHIEF EDITOR, GAZETTEERS & DIRECTOR GENERAL, TRAINING COORDINATION GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ii iii PREFACE The Gazetteer is an authoritative document that describes a District in all its hues–the economy, society, political and administrative setup, its history, geography, climate and natural phenomena, biodiversity and natural resource endowments. It highlights key developments over time in all such facets, whilst serving as a placeholder for the timelessness of its unique culture and ethos. It permits viewing a District beyond the prismatic image of a geographical or administrative unit, since the Gazetteer holistically captures its socio-cultural diversity, traditions, and practices, the creative contributions and industriousness of its people and luminaries, and builds on the economic, commercial and social interplay with the rest of the State and the country at large. The document which is a centrepiece of the District, is developed and brought out by the State administration with the cooperation and contributions of all concerned. Its purpose is to generate awareness, public consciousness, spirit of cooperation, pride in contribution to the development of a District, and to serve multifarious interests and address concerns of the people of a District and others in any way concerned. Historically, the ―Imperial Gazetteers‖ were prepared by Colonial administrators for the six Districts of the then Orissa, namely, Angul, Balasore, Cuttack, Koraput, Puri, and Sambalpur. After Independence, the Scheme for compilation of District Gazetteers devolved from the Central Sector to the State Sector in 1957. -

Thomas Silkstede's Renaissance-Styled Canopied Woodwork in the South Transept of Winchester Cathedral

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 58, 2003, 209-225 (Hampshire Studies 2003) THOMAS SILKSTEDE'S RENAISSANCE-STYLED CANOPIED WOODWORK IN THE SOUTH TRANSEPT OF WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL By NICHOLAS RIALL ABSTRACT presbytery screen, carved in a renaissance style, and the mortuary chests that are placed upon it. In Winchester Cathedral is justly famed for its collection of another context, and alone, Silkstede's work renaissance works. While Silkstede's woodwork has previ might have attracted greater attention. This has ously been described, such studies have not taken full been compounded by the nineteenth century account of the whole piece, nor has account been taken of thealteration s to the woodwork, which has led some important connection to the recently published renaissancecommentator s to suggest that much of the work frieze at St Cross. 'The two sets ofwoodwork should be seen here dates to that period, rather than the earlier in the context of artistic developments in France in the earlysixteent h century Jervis 1976, 9 and see Biddle sixteenth century rather than connected to terracotta tombs1993 in , 260-3, and Morris 2000, 179-211). a renaissance style in East Anglia. SILKSTEDE'S RENAISSANCE FRIEZE INTRODUCTION Arranged along the south wall and part of the Bishop Fox's pelican everywhere marks the archi west wall of the south transept in Winchester tectural development of Winchester Cathedral in Cathedral is a set of wooden canopied stalls with the early sixteenth-century with, occasionally, a ref benches. The back of this woodwork is mosdy erence to the prior who held office for most of Fox's panelled in linenfold arranged in three tiers episcopate - Thomas Silkstede (prior 1498-1524). -

The Deinstallation of a Period Room: What Goes in to Taking One Out

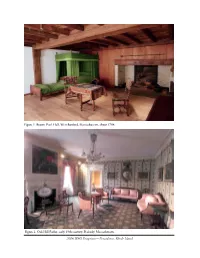

Figure 1. Brown Pearl Hall, West Boxford, Massachusetts, about 1704. Figure 2. Oak Hill Parlor, early 19th century, Peabody, Massachusetts. 2006 WAG Postprints—Providence, Rhode Island The Deinstallation of a Period Room: What Goes in to Taking One Out Gordon Hanlon, Furniture and Frame Conservation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Melissa H. Carr, Masterwork Conservation ABSTRACT Many American museums installed period rooms in the early twentieth century. Eighty years later, different environmental standards and museum expansions mean that some of those rooms need to be removed and either reinstalled or placed in storage. Over the past four years the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has deinstalled all of their European and American period rooms as part of a Master Plan to expand and reorganize the museum. The removal of the rooms was coordinated and supported by museum staff and performed by private contractors. The first part of this paper will discuss the background of the project and the particular issues of the museum to prepare for the deinstallation. The second part will provide an overview of the deinstallation of one specific, painted and fully-paneled room to illustrate the process. It will include comments on the planning, logistics, physical removal and documentation, as well as notes on its future reinstallation. Introduction he Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is in the process of implementing the first phase of a Master Plan which involves the demolition of the east wing of the museum and the building of a new American wing designed by the London-based architect Sir Norman Foster. This project required Tthat the museum’s eighteen period rooms (eleven American and seven European) and two large architec- tural doorways, on display in the east wing and a connector building, be deinstalled and stored during the construction phase. -

Wood Carving, the Presence of Which Is Due to the Fact That Hindu Pilgrims flock I N Great Numbers to Benares from Nepal and Ar E Great Supporters

L IS T OF PLA TES . haukat an r K war C d Jo i i . B kharch n h u a a d Jagmo an . Tti n Carv n and B rass Inla Saharan ur . i g y, p ar Old D r Sah an ur. oo , p ' D D eta l o f Sitfin Baithak and Sada Old o or Saharan ur . i , , , p n r fo r h D l xh Saharanpur Mi stri Carvi g a doo t e e hi Art E ib ition. a n a E n ca n N gi b o y rvi g . S h sham w d screen Farrukha a d . i oo , b ’ Mr H. l All . W ht rkmen aha a Ne son r s wo d. ig , b M2 01 1 8 D E CHA PT R I . THE arts of India are the illustration of the religious life of the Hindus , as that life was already organized in full perfection “ 9 0— 0 M . 0 . 0 3 0 v un der the Code of anu, B E ery detail of “ n a nd l Indian decoration has a religious meani g , the arts of India wil “ n never be rightly understood until these are brought to their study, ot “ li hi m a only the sensibi ty w ch can appreciate the at first sight, but , “ 1 familiar acquaintance with th e character and subjects of the religious a a n d r a poetry, nation l legends, mythological sc iptures that have alw ys i ” been the r inspiration and of which they are the perfected imagery . -

Mitteilungen Der Residenzen-Kommission Der

__________________________________________________ MITTEILUNGEN DER RESIDENZEN-KOMMISSION DER AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN ZU GÖTTINGEN JAHRGANG 10 (2000) NR. 1 MITTEILUNGEN DER RESIDENZEN-KOMMISSION DER AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN ZU GÖTTINGEN JAHRGANG 10 (2000) NR. 1 RESIDENZEN-KOMMISSION ARBEITSSTELLE KIEL ISSN 0941-0937 Herstellung: Vervielfältigungsstelle der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel Titelvignette: Ansicht der Klosteranlage Wienhausen bei Celle von Süden. Kupferstich Merian (1654) INHALT Vorwort ................................................................................................................................ 7 Erziehung und Bildung bei Hofe. 7. Symposium der Residenzen-Kommission in Celle..... 9 Aus der Arbeit der Kommission...........................................................................................13 Die Arbeit der anderen.........................................................................................................15 Politische und soziale Integration am Wiener Hof: Adelige Bestattung als Teil der höfischen Symbol- und Kommunikationsordnung (1620-1850) 1. Kommunikation und Symbole. Ein kulturwissenschaftlicher Horizont der Fragen und Begriffe, von Rudolf Schlögl, Konstanz...................................................15 2. Adelsintegration und Bestattungen, von Mark Hengerer, Konstanz...............................21 Places of Power: Royal Residences and Landscape in Medieval Iberia, von Rita Gomez, Lissabon ...............................................................................................36 -

Parkers Prairie Woodcarving Club JUNE NEWSLETTER

Parkers Prairie Woodcarving Club JUNE NEWSLETTER Marty Dolphen will be having a class on carving one of these Santa’s out of a bass- wood log. We will use a bench for carving. Don’t rush your wood carvings. Any mistake you make is potentially permanent. You’ll have to change up your plan to integrate mistakes into the finished product, and that could sacri- fice your original vision. To avoid this, it helps to lightly sketch out your cuts and carvings Contact for Newsletter & Dues with a pencil. Draw out lines to cut along, and shapes to carve out. It will help you be more precise, and prevent un-fixable mistakes. Roger Thalman 2100 White Oaks Circle N.E. Alexandria, Mn 56308 Email: [email protected] Cell: 320-491-2027 Club dues are due at the first of the year. Adult or Family membership is $15 and Junior membership is $5 Parkers Prairie Woodcarving JUNE NEWSLETTER Parkers Prairie Woodcarving JUNE NEWSLETTER The club is presently on Summer break. We will not be meeting as a Club until this fall. I will continue to send out a monthly Newsletter. In the mean time, keep your tools sharp and the chips flying. Aug 10, 11 & 12: Carv-Fest 2017 Faribault, Minnesota Alexandria Park .. Ice Arena 1816 NW 2nd Ave 60 plus 1-day workshops. Some of the instructors are Bob Lawrence, Alice Spadgenske, Don Fischer and many others. Meet new friends, learn from top instructors, buy top of the line art work and mix with who’s-who of Carving. -

Autocratie Ou Polyarchie ? La Lütte Pour Le Pouvoir Politique En Flandre

Autocratie ou polyarchie ? La lütte pour le pouvoir politique en Flandre de 1482 a 1492, d'apres des documents inedits par W. P. BLOCKMANS «II n'y a guere d'opoque, dans nos annales, plus confuse, plus mal oclaircie, que celle dont le point de dopart est la mort de Charles le Hardi, duc de Bourgogne, et qui finit ä l'avenement au trone de son petit-fils, l'archiduc Philippe le Beau» (i). Plus d'un siecle apres le moment oü Gachard 6crivit ces lignes dans l'introduction de son impressionnante odition de lettres concernant la pöriode envisagoe, nos connaissances ne se sont pas beaucoup otendues au-delä de ce que le grand archiviste en commu- niqua. Et pourtant, cette meme poriode nous semble cruciale dans l'histoire de notre pays, parce que les forces essentielles des gouvernants et des gouvern6s y atteignent un point culminant en un affrontement parfois violent Je tiens ä exprimer ici ma profonde gratitude envers Messieurs A. Verfaulst, M.-A. Arnould, J. Buntinx et ä M. et Mme R. Wellens- De Donder qui, par leurs nombreux conseils et par leurs remarques judicieuses, ont contribud d'une maniere substantielle ä l'elabo- ration de cette publication. (i) L.P. GACHARD, Lettres ineditcs de Maximilien, duc d'Autriche, roi des Romains et empereur, sur les affaires des Pays-Bas, de 1477 ä 1508, dans : Bulletin de la Commission royale d'Histoire, 2e Serie, II, 1851, pp. 263-452 et III, 1851, pp. 193-328, notamment p. 263. 258 W. P. BLOCKMANS et extremement long. L'issue de ce conflit, proparo par bien d'autres, determina les relations du pouvoir pendant plusieurs ddcennies. -

Airstep Advantage® • Airstep Evolution® Airstep Plus® • Armorcoretm Pro UR • Armorcoretm Pro

® Featuring AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring DREAMTM Economy Match: 27" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88080 Nap Time 88081 Free Fall 88082 Daybreak WONDERTM Economy Match: 6" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88050 Dandelion Puff 88054 Porpoise SAVORTM Economy Match: 54" L x 72" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88000 Clam Chowder 88001 Warm Croissant 88002 Cookies n’ Cream 88003 Pecan Pie 88004 Beluga Caviar 88005 Sushi 1 ® Featuring AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring PLAYTIMETM Economy Match: Random L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88010 Hop Scotch 88011 Swing Set 88013 Hide and Seek 88014 Board Game 88015 Tree House TM REMINISCE CURIOUSTM Economy Match: 9" L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets Economy Match: Random L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88060 First Snowfall 88061 Catching Fireflies 88062 Counting Stars 88041 Presents 88042 Magic Trick UNWINDTM Economy Match: 27" L x 13.09" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88030 Mountain Air 88031 Weekend in the 88032 Sunday Times 88033 Cup of Tea Country MYSTICTM Economy Match: 18" L x 16" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88070 Harp Strings 88071 Knight's Shadow 88072 Himalayan Trek 2 ® Featuring AirStep Evolution Sheet Flooring CASA NOVATM Economy Match: 27" L x 13.09" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72140 San Pedro Morning 72141 Desert View 72142 Cabana Gray 72143 La Paloma Shadows KALEIDOSCOPETM Economy Match: 18" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72150 Paris Rain 72151 Palisades Park 72152 Roxbury Caramel 72153 Fresco Urbain LIBERTY SQUARETM Economy Match: 18" L x 18" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72160 Blank Canvas 72161 Parkside Dunes -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

A Royal Crusade History: the Livre D'eracles and Edward IV's Exile In

A Royal Crusade History: The Livre d’Eracles and Edward IV’s Exile in Burgundy Erin K. Donovan The English King Edward IV (1442-83) had throughout his reign many political, familial, and cultural connections with the Flanders-based court of Burgundy, headed at the time by Duke Charles the Bold. In 1468, King Edward arranged for his sister Margaret of York to marry Duke Charles of Burgundy. The same year he was inducted into Charles’s powerful Burgundian chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece and reciprocally inducted Charles into the English Order of the Garter. In 1470, he was forced into exile for five months when the Earl of Warwick, Richard Neville, placed the former King Henry VI back on the throne. After first unsuccessfully trying to find shelter in Calais, Edward landed in Holland where he was hospitably taken in by Burgundian nobleman Louis de Gruuthuse (also known as Louis de Bruges) at his home in The Hague, and afterwards in Flanders at Louis’s home in Bruges.1 Between 1470 and 1471, Edward was witness to and inspired by the flourishing Flemish culture of art and fashion, including the manuscript illuminations that his host Louis was beginning voraciously to consume at the time. While Edward was in exile he was penniless, and thus unable to commission works of art. However, after his victorious return to the throne in 1471 he had the full resources of his realm at his command again, and over time I would like to extend my deep thanks to the many participants of the British Library’s Royal Manuscripts Conference, held 12-13 December 2011, who provided me with fruitful suggestions to extend my paper’s analysis. -

5. Wood Carving Tools

Session 4 [Wednesday 4th period 2.0 hours - Main Hall] Artistic aspects of wood use and design Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 1 Speakers Speaker: M P Ranjan Topic: Entrepreneur Development, Design and Innovation in Wood Products / Design Detailing in Wood: An Appreciation of Furniture Design by Gajanan Upadhaya Speaker: Jirawat Tangkijgamwong Topic: The Way of Wood: Finding Green Pieces in Thailand Speaker: Achmad Zainudin Topic: Jepara: Mirror of Indonesian Art Wood Speaker: Hakki Alma Topic: Wood Carving Art in Turkey Speaker: Lv Jiufang Topic: Wood Aesthetic Pattern Design and its Application Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 2 Entrepreneur Development, Design and Innovation in Wood Products / Design Detailing in Wood: An Appreciation of Furniture Design by Gajanan Upadhaya M P Ranjan1 1 Designer, National Institute of Design (retired), Ahmedabad, India ([email protected]) Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 3 Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 4 Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 5 Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 6 Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 7 Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 8 Proceedings of the -

Jean Froissart, Chroniques 1992-2013

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TORINO DIPARTIMENTO DI LINGUE E LETTERATURE STRANIERE E CULTURE MODERNE CORSO DI LAUREA IN SCIENZE DEL TURISMO A.A. 2013/2014 TESI DI LAUREA TRIENNALE _____________________________________________ CHRONIQUES DI JEAN FROISSART --- BIBLIOGRAFIA RECENTE _____________________________________________ Relatore Prof. Giovanni Matteo Roccati Candidato Loris Bergagna Matricola: 703780 2 SOMMARIO Premessa ……………………………………………………………………………….. p. 3 Classificazione della bibliografia ……………………………………………………... p. 6 Chroniques di Jean Froissart - Bibliografia recente (1992-2013) ………………… p. 9 Edizioni ………………………………………………………………………………….. p. 10 Studi sui testimoni (manoscritti, produzione libraria) ………………………………..p. 13 Traduzioni ………………………………………………………………………………. p. 15 Studi generali sulle Chroniques ………………………………………………………. p. 17 Diffusione e ricezione dell’opera ………………………………………………………p. 18 Scrittura …………………………………………………………………………………. p. 21 Tematiche generali …………………………………………………………………….. p. 23 Eventi ……………………………………………………………………………………. p. 32 Personaggi ……………………………………………………………………………… p. 36 Riferimenti geografici e all’ambiente naturale ………………………………………. p. 41 Rapporto con altri autori ………………………………………………………………. p. 45 Rapporto testo-immagine ………………………………………………………………p. 46 Conclusioni ………………………………………………………………………………p. 52 Indice bibliografico ………………………………………………………………………p. 53 3 PREMESSA Lo scopo della presente tesi di laurea è di fornire la bibliografia, analizzata metodicamente, concernente le Chroniques di Jean Froissart, uscita nel periodo compreso