Character and Opinion in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopian Promise

Unit 3 UTOPIAN PROMISE Puritan and Quaker Utopian Visions 1620–1750 Authors and Works spiritual decline while at the same time reaffirming the community’s identity and promise? Featured in the Video: I How did the Puritans use typology to under- John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity” (ser- stand and justify their experiences in the world? mon) and The Journal of John Winthrop (journal) I How did the image of America as a “vast and Mary Rowlandson, A Narrative of the Captivity and unpeopled country” shape European immigrants’ Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (captivity attitudes and ideals? How did they deal with the fact narrative) that millions of Native Americans already inhabited William Penn, “Letter to the Lenni Lenapi Chiefs” the land that they had come over to claim? (letter) I How did the Puritans’ sense that they were liv- ing in the “end time” impact their culture? Why is Discussed in This Unit: apocalyptic imagery so prevalent in Puritan iconog- William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (history) raphy and literature? Thomas Morton, New English Canaan (satire) I What is plain style? What values and beliefs Anne Bradstreet, poems influenced the development of this mode of expres- Edward Taylor, poems sion? Sarah Kemble Knight, The Private Journal of a I Why has the jeremiad remained a central com- Journey from Boston to New York (travel narra- ponent of the rhetoric of American public life? tive) I How do Puritan and Quaker texts work to form John Woolman, The Journal of John Woolman (jour- enduring myths about America’s -

February 7, 2021

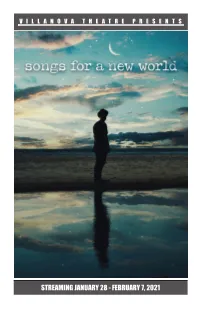

VILLANOVA THEATRE PRESENTS STREAMING JANUARY 28 - FEBRUARY 7, 2021 About Villanova University Since 1842, Villanova University’s Augustinian Catholic intellectual tradition has been the cornerstone of an academic community in which students learn to think critically, act compassionately and succeed while serving others. There are more than 10,000 undergraduate, graduate and law students in the University’s six colleges – the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Villanova School of Business, the College of Engineering, the M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, the College of Professional Studies and the Villanova University School of Law. As students grow intellectually, Villanova prepares them to become ethical leaders who create positive change everywhere life takes them. In Gratitude The faculty, staff and students of Villanova Theatre extend sincere gratitude to those generous benefactors who have established endowed funds in support of our efforts: Marianne M. and Charles P. Connolly Jr. ’70 Dorothy Ann and Bernard A. Coyne, Ph.D. ̓55 Patricia M. ’78 and Joseph C. Franzetti ’78 The Donald R. Kurz Family Peter J. Lavezzoli ’60 Patricia A. Maskinas Msgr. Joseph F. X. McCahon ’65 Mary Anne C. Morgan ̓70 and Family & Friends of Brian G. Morgan ̓67, ̓70 Anthony T. Ponturo ’74 Eric J. Schaeffer and Susan Trimble Schaeffer ’78 The Thomas and Tracey Gravina Foundation For information about how you can support the Theatre Department, please contact Heather Potts-Brown, Director of Annual Giving, at (610) 519-4583. gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our many patrons & subscribers. We wish to offer special thanks to our donors. 20-21 Benefactors A Running Friend William R. -

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

Rev 21: 10, and in the Spirit the Angel Carried Me Away to a Great, High Mountain and Showed Me the Holy City Jerusalem Coming Down out of Heaven from God

June 28, 2020 Rev. Jane Florence Title: Living a Dream or a Nightmare Text: Revelation 21 News flash: the world didn't end on Dec. 21, 2012. You've probably already figured that out for yourself. Maybe you remember all the warnings leading up to the end of 2012- the prophets and websites announced the end of the world. For years leading up to 2012, we were warned of an ancient Maya prophecy predicting the end of the world as their calendar signaled, or the end of the world due to a mysterious planet on a collision course with Earth for 2012 , or a reverse in Earth's rotation would cause all polarity on the planet to reverse. In spite of our best scientists, even NASA, telling people all these perditions lacked any scientific data, people still waited for the end of the world as we know it on Dec12, 2012. Okay, so it didn’t happen. Maybe those harbingers got the date reversed, was it a pre- apocalyptic dyslexia? Maybe it wasn’t 2012, but 2021! in which case our experience in 2020 might make sense. If we look back at ancient texts, people have been envisioning dramatic earth changes for ages. In John’s vision of Revelation, he too sees the end of the world- as we know it, but he does not see the destruction of the earth as modern predictions maintain. Listen with me to the 21st chapter in the Book of Revelation , the last book in the Christian scriptures: Rev 21: 10, And in the spirit the angel carried me away to a great, high mountain and showed me the holy city Jerusalem coming down out of heaven from God. -

From Columbus to Acosta: Science

FromColumbus to Acosta: Science, Geography,and the New World KarlW. Butzer Departmentof Geography,University of Texasat Austin,Austin, TX 78712, FAX 512/471-5049 Abstract.What is called the Age of Discovery peoples probably put observers with rural evokes imagesof voyages,nautical skills, and backgroundson an equal footingwith those maps. Yet the Europeanencounter with the steeped in traditionalacademic curricula.Last Americasalso led to an intellectualconfronta- butnot least,the essaypoints up the enormity tionwith the naturalhistory and ethnography of the primarydocumentation, compiled by of a "new" world.Contrary to the prevailing these Spanishcontributors during the century view of intellectualstasis, this confrontation after1492, most of it awaitinggeographical re- provokednovel methods of empiricaldescrip- appraisal. tion, organization,analysis, and synthesisas KeyWords: Acosta,Columbus, ethnography, geo- Medievaldeductivism and Classicalontogen- graphicalplanning, gridiron towns, historyof sci- ies proved to be inadequate. This essay ence, landforms,L6pez de Velasco, naturalhistory, demonstrateshow the agentsof thatencoun- New World landscapes, Oviedo, relaciones ter-sailors, soldiers, governmentofficials, geograficas,Renaissance, Sahagun, Spanish geogra- and missionaries-madesense of these new phy. landsand peoples; ithighlights seven method- ological spheres, by examiningthe work of The worldis so vastand beautiful,and containsso exemplaryindividuals who illustratethe di- manythings, each differentfrom the other. verse backgrounds,abilities, -

George Santayana: a Critical Anomaly Carol Ann Erickson University of Nebraska at Omaha

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 2-1966 George Santayana: A critical anomaly Carol Ann Erickson University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Erickson, Carol Ann, "George Santayana: A critical anomaly" (1966). Student Work. 55. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/55 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE 1SANT.A.YANA, CRITICAL ANOMALY A Thesis J 4;) Presented to the Department o.f English and the Fa~ulty or the Oollege of Graduate Studies :University of Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degre& Master of Arts by -Carol A. Erickson February 1966 UM I Number: EP72700 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material ~ad to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ' UMf. UMI EP72700 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 13'1·6 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 - 1346 Accepted for the faculty of the College of Graduate Studies of the University of Omaha, 1n_part1al fulfillment of.the requirements for the degree Master of Arts. -

Report on Civil Rights Congress As a Communist Front Organization

X Union Calendar No. 575 80th Congress, 1st Session House Report No. 1115 REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS AS A COMMUNIST FRONT ORGANIZATION INVESTIGATION OF UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES IN THE UNITED STATES COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ^ EIGHTIETH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Public Law 601 (Section 121, Subsection Q (2)) Printed for the use of the Committee on Un-American Activities SEPTEMBER 2, 1947 'VU November 17, 1947.— Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1947 ^4-,JH COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES J. PARNELL THOMAS, New Jersey, Chairman KARL E. MUNDT, South Dakota JOHN S. WOOD, Georgia JOHN Mcdowell, Pennsylvania JOHN E. RANKIN, Mississippi RICHARD M. NIXON, California J. HARDIN PETERSON, Florida RICHARD B. VAIL, Illinois HERBERT C. BONNER, North Carolina Robert E. Stripling, Chief Inrestigator Benjamin MAi^Dt^L. Director of Research Union Calendar No. 575 SOth Conokess ) HOUSE OF KEriiEfcJENTATIVES j Report 1st Session f I1 No. 1115 REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS AS A COMMUNIST FRONT ORGANIZATION November 17, 1917. —Committed to the Committee on the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. Thomas of New Jersey, from the Committee on Un-American Activities, submitted the following REPORT REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS 205 EAST FORTY-SECOND STREET, NEW YORK 17, N. T. Murray Hill 4-6640 February 15. 1947 HoNOR.\RY Co-chairmen Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Dr. Harry F. Ward Chairman of the board: Executive director: George Marshall Milton Kaufman Trea-surcr: Field director: Raymond C. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Theology of Supernatural

religions Article Theology of Supernatural Pavel Nosachev School of Philosophy and Cultural Studies, HSE University, 101000 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: The main research issues of the article are the determination of the genesis of theology created in Supernatural and the understanding of ways in which this show transforms a traditional Christian theological narrative. The methodological framework of the article, on the one hand, is the theory of the occulture (C. Partridge), and on the other, the narrative theory proposed in U. Eco’s semiotic model. C. Partridge successfully described modern religious popular culture as a coexistence of abstract Eastern good (the idea of the transcendent Absolute, self-spirituality) and Western personified evil. The ideal confirmation of this thesis is Supernatural, since it was the bricolage game with images of Christian evil that became the cornerstone of its popularity. In the 15 seasons of its existence, Supernatural, conceived as a story of two evil-hunting brothers wrapped in a collection of urban legends, has turned into a global panorama of world demonology while touching on the nature of evil, the world order, theodicy, the image of God, etc. In fact, this show creates a new demonology, angelology, and eschatology. The article states that the narrative topics of Supernatural are based on two themes, i.e., the theology of the spiritual war of the third wave of charismatic Protestantism and the occult outlooks derived from Emmanuel Swedenborg’s system. The main topic of this article is the role of monotheistic mythology in Supernatural. -

Justus Buchler Biography

Justus Buchler Biography Table of Contents BookRags Biography....................................................................................................1 Justus Buchler.......................................................................................................1 Copyright Information..........................................................................................1 Justus Buchler Biography............................................................................................2 Works....................................................................................................................2 Further Reading....................................................................................................5 Dictionary of Literary Biography Biography.......................................................8 i BookRags Biography Justus Buchler For the online version of BookRags' Justus Buchler Biography, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/biography/justus−buchler−dlb/ Copyright Information Kathleen A. Wallace, Hofstra University.. Dictionary of Literary Biography. ©2005−2006 Thomson Gale, a part of the Thomson Corporation. All rights reserved. (c)2000−2006 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BookRags Biography 1 Justus Buchler Biography Name: Justus Buchler Birth Date: March 27, 1914 Death March 19, 1991 Date: Nationality: American Gender: Male Works WRITINGS BY THE AUTHOR:BOOKS • Charles Peirce's Empiricism (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1939; New York: -

The Letters of George Santayana Book Two, 1910—1920

The Letters of George Santayana Book Two, 1910—1920 To Josephine Preston Peabody Marks [1910 or 1911] • Cambridge, Massachusetts (MS: Houghton) COLONIAL CLUB CAMBRIDGE Dear Mrs Marks1 Do you believe in this “Poetry Society”? Poetry = solitude, Society = prose, witness my friend Mr. Reginald Robbins!2 I may still go to the dinner, if it comes during the holidays. In that case, I shall hope to see you there. Yours sincerely GSantayana 1Josephine Preston Peabody (1874–1922) was a poet and dramatist whose plays kept alive the tradition of poetic drama in America. Her play, The Piper, was produced in 1909. She was married to Lionel Simeon Marks, a Harvard mechanical engineering professor. 2Reginald Chauncey Robbins (1871–1955) was a writer who took his A.B. from Harvard in 1892 and then did graduate work there. To William Bayard Cutting Sr. [January 1910] • [Cambridge, Massachusetts] (MS: Unknown) His intellectual life was, without question, the most intense, many-sided and sane that I have ever known in any young man,1 and his talk, when he was in college, brought out whatever corresponding vivacity there was in me in those days, before the routine of teaching had had time to dull it as much as it has now … I always felt I got more from him than I had to give, not only in enthu- siasm—which goes without saying—but also in a sort of multitudinousness and quickness of ideas. [Unsigned] 1William Bayard Cutting Jr. (1878–1910) was a member of the Harvard class of 1900. He served as secretary of the vice consul in the American consulate in Milan (1908–9) and Secretary of the American Legation, Tangier, Morocco (1909). -

The American Philosophical Association EASTERN DIVISION ONE HUNDRED TENTH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM

The American Philosophical Association EASTERN DIVISION ONE HUNDRED TENTH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM BALTIMORE MARRIOTT WATERFRONT BALTIMORE, MARYLAND DECEMBER 27 – 30, 2013 Important Notices for Meeting Attendees SESSION LOCATIONS Please note: the locations of all individual sessions will be included in the paper program that you will receive when you pick up your registration materials at the meeting. To save on printing costs, the program will be available only online prior to the meeting; with the exception of plenary sessions, the online version does not include session locations. In addition, locations for sessions on the first evening (December 27) will be posted in the registration area. IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT REGISTRATION Please note: it costs $40 less to register in advance than to register at the meeting. The advance registration rates are the same as last year, but the additional cost of registering at the meeting has increased. Online advance registration at www.apaonline.org is available until December 26. 1 Friday Evening, December 27: 6:30–9:30 p.m. FRIDAY, DECEMBER 27 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEETING 1:00–6:00 p.m. REGISTRATION 3:00–10:00 p.m., registration desk (third floor) PLACEMENT INFORMATION Interviewers and candidates: 3:00–10:00 p.m., Dover A and B (third floor) Interview tables: Harborside Ballroom, Salons A, B, and C (fourth floor) FRIDAY EVENING, 6:30–9:30 P.M. MAIN PROGRAM SESSIONS I-A. Symposium: Ancient and Medieval Philosophy of Language THIS SESSION HAS BEEN CANCELLED. I-B. Symposium: German Idealism: Recent Revivals and Contemporary Relevance Chair: Jamie Lindsay (City University of New York–Graduate Center) Speakers: Robert Brandom (University of Pittsburgh) Axel Honneth (Columbia University) Commentator: Sally Sedgwick (University of Illinois–Chicago) I-C.