Owens Corning Records, 1938-Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aremco—High Temperature Solutions

High Temperature Solutions Since 1965, our success has been a result of this simple business strategy: • Understanding Customer Requirements. • Providing Outstanding Service and Support. • Producing High Quality Technical Materials and Equipment. • Solving Difficult Technical Problems. CONTENTS Technical Bulletin Page No. A1 Machinable & Dense Ceramics .......................................................... 2 A2 High Temperature Ceramic & Graphite Adhesives ....................... 6 A3 High Temperature Ceramic-Metallic Pastes .................................12 A4 High Temperature Potting & Casting Materials ...........................14 A5-S1 High Temperature Electrical Coatings & Sealants ......................18 A5-S2 High Temperature High Emissivity Coatings ................................20 A5-S3 High Temperature Thermal Spray Sealants ..................................22 A5-S4 High Temperature Coatings for Ceramics, Glass & Quartz ......24 A5-S5 High Temperature Refractory Coatings .........................................26 A6 High Temperature Protective Coatings ..........................................28 A7 High Performance Epoxies ................................................................34 A8 Electrically & Thermally Conductive Materials .............................36 A9 Mounting Adhesives & Accessories ................................................38 A10 High Temperature Tapes ...................................................................42 A11 High Temperature Inorganic Binders..............................................44 -

Leasing Brochure

ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES FRANKLIN PARK ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES FRANKLIN PARK MALL #COMETOGETHER FASHION FAMILY FUN FOOD FASHION FAMILY FUN FOOD Franklin Park Mall is a super-regional shopping center located in Toledo, Ohio offering the PROPERTY INFO area’s premier selection of shopping, dining and entertainment options. The 1.3 million sq. ft. center is positioned in a rapidly expanding retail corridor and features exceptional freeway access to Toledo’s interstates and the Ohio Turnpike. Franklin Park Mall is the BUILT 1971 only enclosed shopping center within a 50-mile radius and welcomes more than 6 million REDEVELOPED 2005 visitors per year from surrounding Northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan communities. TOTAL TENANTS 150+ The community destination is anchored by Dillard’s, Macy’s, JCPenney, Dick’s Sporting TOTAL CENTER GLA 1,300,000 SF Goods, a Cinemark 16 & XD theater and is home to 150+ local, regional and national DAILY VISITORS 16,400+ retailers. Visitors can enjoy the region’s only Dave & Buster’s, BJ’s Brewhouse and Apple Store as well as many first-to-market retailers including Altar’d State, Dry Goods and Box ANNUAL VISITORS 6+ MILLION Lunch. A bright and airy Food Court serving fast casual favorites such as Chick-Fil-A, PARKING SPACES 6,100 Steak Escape, Auntie Anne’s and Sbarro compliment an impressive lineup of full-service restaurants including Black Rock Bar & Grill, Bravo!, bd’s Mongolian Grill and Don Juan Mexican Restaurant. ANNUAL SALES As the fourth largest city in the state of Ohio, Toledo has the amenities of a lively metropolis and the charm of a small town. -

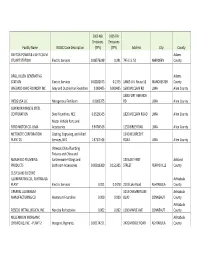

Facility Name NEISIC Code Description 2005 NEI Emissions

2005 NEI 2005 TRI Emissions Emissions Facility Name NEISIC Code Description (TPY) (TPY) Address City County DAYTON POWER & LIGHT CO JM Adams STUART STATION Electric Services 0.08576238 0.291 745 U.S. 52 ABERDEEN County DP&L, KILLEN GENERATING Adams STATION Electric Services 0.02182673 0.1375 14869 U.S. Route 52 MANCHESTER County WHEMCO‐OHIO FOUNDRY INC Gray and Ductile Iron Foundries 0.000405 0.000405 1600 MCCLAIN RD LIMA Allen County 1900 FORT AMANDA INEOS USA LLC Nitrogenous Fertilizers 0.0002375 RD LIMA Allen County SUPERIOR FORGE & STEEL CORPORATION Steel Foundries, NEC 6.0526E‐05 1820 MCCLAIN ROAD LIMA Allen County Motor Vehicle Parts and FORD MOTOR CO.‐LIMA Accessories 3.9474E‐06 1155 BIBLE ROAD LIMA Allen County METOKOTE CORPORATION Coating, Engraving, and Allied 1340 NEUBRECHT PLANT 25 Services, NEC 1.9737E‐06 ROAD LIMA Allen County Vitreous China Plumbing Fixtures and China and MANSFIELD PLUMBING Earthenware Fittings and 150 EAST FIRST Ashland PRODUCTS Bathroom Accessories 0.00019309 0.151905 STREET PERRYSVILLE County CLEVELAND ELECTRIC ILLUMINATING CO., ASHTABULA Ashtabula PLANT Electric Services 0.021 0.0178 2133 Lake Road ASHTABULA County GENERAL ALUMINUM 1043 CHAMBERLAIN Ashtabula MANUFACTURING CO Aluminum Foundries 0.009 0.009 BLVD CONNEAUT County Ashtabula FOSECO METALLURGICAL INC. Nonclay Refractories 0.002 0.002 1100 MAPLE AVE CONNEAUT County MILLENNIUM INORGANIC Ashtabula CHEMICALS, INC. ‐ PLANT 2 Inorganic Pigments 0.00174211 2426 MIDDLE ROAD ASHTABULA County 2005 NEI 2005 TRI Emissions Emissions Facility Name NEISIC Code Description (TPY) (TPY) Address City County Primary Production of Ashtabula ROCK CREEK ALUMINUM INC Aluminum 0.001 0.001 2639 E. -

Oppose the Proposed Terminatiion of Judgement in U.S. V. Association of Casualty and Surety Companies, Et

SOCIETY OF COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS Toll Free Phone (877) 841-0660 • Toll Free Fax 877-851-0660 Website: www.scrs.com • E-Mail: [email protected] • Mailing: P.O. Box 3037, Mechanicsville, VA 23116 Executive Officers: Brett Bailey (816) 741-6966 Chairman Missouri August 20, 2019 Bruce Halcro (406) 442-8611 U.S. Department of Justice Vice-Chairman Montana 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Amber Alley (415) 994-7913 Secretary California Washington, DC 20530-0001 Tim Ronak (949) 289-3357 Treasurer California RE: Oppose the proposed termination of judgement in U.S. v. Association of Paul Sgro (732) 222-3644 Casualty and Surety Companies, et al Director-at-Large New Jersey Kye Yeung (714) 957-1290 Immediate Past Chairman California Attorney General William Barr and the U.S. Department of Justice, National Directors: Michael Bradshaw (828) 569-1275 We write to you in opposition of the proposed termination of judgement in the U.S. v. North Carolina Association of Casualty and Surety Companies, et al, otherwise referred to as the 1963 Domenic Brusco (724) 931-3063 Pennsylvania Consent Decree. Trace Coccimiglio (801) 576-8585 Utah The Society of Collision Repair Specialists (SCRS) serves as a not-for-profit national Dave Gruskos (732) 747-1770 association representing the hardworking collision repair facilities and specialized New Jersey professionals who work to repair collision-damaged vehicles across the United States. Jeff Kallemeyn (630) 257-2277 Illinois Matthew McDonnell (406) 259-6328 There is nothing more paramount than protecting consumer safety and maintaining a fair Montana and competitive landscape that ensures consumers can count on their insurance contracts Robert Grieve (303) 761-9219 Colorado to fairly indemnify them for loss in the event of an unfortunate accident. -

In the Matter of Owens Corning

0610281 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS: Deborah Platt Majoras, Chairman Pamela Jones Harbour Jon Leibowitz William E. Kovacic J. Thomas Rosch ____________________________________ ) ) ) In the Matter of ) ) OWENS CORNING, ) Docket No. C- ) a corporation. ) ) ) ) ____________________________________) COMPLAINT Pursuant to the provisions of the Federal Trade Commission Act and of the Clayton Act, and by virtue of the authority vested by said Acts, the Federal Trade Commission (the “Commission”), having reason to believe that respondent Owens Corning (“Owens Corning”), a corporation, and Compagnie de Saint Gobain (“Saint Gobain”), a corporation, both subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission, have agreed to an acquisition by Owens Corning of certain fiberglass reinforcements and composite fabrics assets of Saint Gobain in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. § 18, and Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. § 45, and it appearing to the Commission that a proceeding in respect thereof would be in the public interest, hereby issues its Complaint, stating its charges as follows: I. RESPONDENT 1. Respondent Owens Corning is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of Delaware, with its principal place of business at One Owens Corning Parkway, Toledo, Ohio, 43659. Owens Corning is a global company engaged in a wide variety of businesses, including the development, manufacture, marketing, and sale of glass fiber reinforcements. 1 II. JURISDICTION 2. Owens Corning is, and at all times relevant herein has been, engaged in commerce as “commerce” is defined in Section 1 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. -

Fiber Optic Cable for VOICE and DATA TRANSMISSION Delivering Solutions Fiber Optic THAT KEEP YOU CONNECTED Cable Products QUALITY

Fiber Optic Cable FOR VOICE AND DATA TRANSMISSION Delivering Solutions Fiber Optic THAT KEEP YOU CONNECTED Cable Products QUALITY General Cable is committed to developing, producing, This catalog contains in-depth and marketing products that exceed performance, information on the General Cable quality, value and safety requirements of our line of fiber optic cable for voice, customers. General Cable’s goal and objectives video and data transmission. reflect this commitment, whether it’s through our focus on customer service, continuous improvement The product and technical and manufacturing excellence demonstrated by our sections feature the latest TL9000-registered business management system, information on fiber optic cable the independent third-party certification of our products, from applications and products, or the development of new and innovative construction to detailed technical products. Our aim is to deliver superior performance from all of General Cable’s processes and to strive for and specific data. world-class quality throughout our operations. Our products are readily available through our network of authorized stocking distributors and distribution centers. ® We are dedicated to customer TIA 568 C.3 service and satisfaction – so call our team of professionally trained sales personnel to meet your application needs. Fiber Optic Cable for the 21st Century CUSTOMER SERVICE All information in this catalog is presented solely as a guide to product selection and is believed to be reliable. All printing errors are subject to General Cable is dedicated to customer service correction in subsequent releases of this catalog. and satisfaction. Call our team of professionally Although General Cable has taken precautions to ensure the accuracy of the product specifications trained sales associates at at the time of publication, the specifications of all products contained herein are subject to change without notice. -

Through a Glass Darkly: the Case Against Pilkington Plc. Under the New U.S

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 16 Issue 2 Winter Winter 1996 Through a Glass Darkly: The aC se against Pilkington plc. under the New U.S. Department of Justice International Enforcement Policy Jeffrey N. Neuman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey N. Neuman, Through a Glass Darkly: The asC e against Pilkington plc. under the New U.S. Department of Justice International Enforcement Policy, 16 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 284 (1995-1996) This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Through a Glass Darkly: The Case Against Pilkington plc. under the New U.S. Department of Justice International Enforcement Policy Jeffrey N. Neuman Trade and commerce, if they were not made of India-rubber,would never manage to bounce over the obstacles which legislatorsare continually put- ting in their way... - Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience I. INTRODUCTION A complaint and consent decree filed on May 25, 1994 by the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice against Pilk- ington plc., a British fiat glass manufacturer, is yet another indication that tough Federal Government antitrust enforcement policy is back in vogue.' The Government's complaint alleged that Pilkington's 1 United States v. Pilkington plc, 6 Trade Reg. -

OWENS CORNING, SAINT-GOBAIN INTENTAN FUSIONAR SUS NEGOCIOS DE REFUERZOS Página 3 También En Este Número

Vol. I, Núm. 3 – 2006 OWENS CORNING, SAINT-GOBAIN INTENTAN FUSIONAR SUS NEGOCIOS DE REFUERZOS Página 3 También en este número: Un mensaje de Chuck Dana Presidente de Composite Solutions Business, Owens Corning Página 2 Tubos plásticos reforzados con fibra de vidrio: la aplicación inicial aún crece Los composites continúan combatiendo la corrosión en los yacimientos de petróleo Página 4 Combinación ganadora El valor y la innovación impulsan el crecimiento de los composites en Europa Página 6 Ecología Crece la responsabilidad en el área de los composites Página 8 El uso de estructuras y caños de composites está creciendo en las plataformas de petróleo con el fin de reducir el peso y resistir la corrosión. Página 4 UN MENSAJE DE CHUCK DANA PRESIDENTE DE COMPOSITE SOLUTIONS BUSINESS, OWENS CORNING Han pasado tantas cosas desde la última A principios de mayo, finalizamos nuestra compra del negocio edición de esta revista que no sé por de composites de Asahi Fiber Glass Co., Ltd. de Japón. La adición dónde empezar. Comencemos con las de capacidad de fabricación en esa región nos permite entregarle grandes noticias de que Owens Corning más valor a usted y a otros clientes de todo el mundo. Además, y Saint-Gobain se encuentran en los productos y la tecnología adquiridos allí servirán de respaldo negociaciones para fusionar el negocio a nuestro negocio porque nos permitirán crear una gama más Reinforcement Business de Owens Corning amplia de soluciones de composites en varios mercados. con el negocio de refuerzos y composites de Saint-Gobain. Esta fusión unirá a dos También a principios de mayo, Owens Corning anunció que pioneros de la industria que tienen amplia experiencia en la llegó a un acuerdo con sus acreedores clave en un Plan de innovación de productos y una larga tradición de enfoque reorganización que allana el camino para que la compañía en el cliente. -

Fluidized Bed Chemical Vapor Deposition of Zirconium Nitride Films

INL/JOU-17-42260-Revision-0 Fluidized Bed Chemical Vapor Deposition of Zirconium Nitride Films Dennis D. Keiser, Jr, Delia Perez-Nunez, Sean M. McDeavitt, Marie Y. Arrieta July 2017 The INL is a U.S. Department of Energy National Laboratory operated by Battelle Energy Alliance INL/JOU-17-42260-Revision-0 Fluidized Bed Chemical Vapor Deposition of Zirconium Nitride Films Dennis D. Keiser, Jr, Delia Perez-Nunez, Sean M. McDeavitt, Marie Y. Arrieta July 2017 Idaho National Laboratory Idaho Falls, Idaho 83415 http://www.inl.gov Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy Under DOE Idaho Operations Office Contract DE-AC07-05ID14517 Fluidized Bed Chemical Vapor Deposition of Zirconium Nitride Films a b c c Marie Y. Arrieta, Dennis D. Keiser Jr., Delia Perez-Nunez, * and Sean M. McDeavitt a Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 b Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, Idaho 83401 c Texas A&M University, Department of Nuclear Engineering, College Station, Texas 77840 Received November 11, 2016 Accepted for Publication May 23, 2017 Abstract — – A fluidized bed chemical vapor deposition (FB-CVD) process was designed and established in a two-part experiment to produce zirconium nitride barrier coatings on uranium-molybdenum particles for a reduced enrichment dispersion fuel concept. A hot-wall, inverted fluidized bed reaction vessel was developed for this process, and coatings were produced from thermal decomposition of the metallo-organic precursor tetrakis(dimethylamino)zirconium (TDMAZ) in high- purity argon gas. Experiments were executed at atmospheric pressure and low substrate temperatures (i.e., 500 to 550 K). Deposited coatings were characterized using scanning electron microscopy, energy dispersive spectroscopy, and wavelength dis-persive spectroscopy. -

Owens Corning I 2013 Fact Sheet

owenS Corning | 2013 faCt Sheet www.owenscorning.com Owens Corning’s three primary 2012 Sales: Employees: Countries: businesses: Composites, Roofing, and $5.2 Billion 15,000 27 Insulation, provide market, geographic, and customer diversity. The company operates in markets with attractive long- Company overview Owens Corning and its family of companies are a leading global term macro drivers, including global industrial producer of residential and commercial building materials, glass-fiber reinforcements, and production, material substitution, U.S. housing, engineered materials for composite systems. A Fortune® 500 company for 58 consecutive and energy efficiency. years, the company is committed to driving sustainability by delivering solutions, transforming markets, and enhancing lives. Celebrating its 75th anniversary in 2013, Owens Corning has U.S. & Canada New Residential Construction earned its reputation as a market-leading innovator of glass-fiber technology by consistently providing new solutions that deliver a strong combination of quality and value to its U.S. & Canada Residential Repair & Remodeling customers across the world. U.S. & Canada The company operates within two segments: Composite Solutions and Building Commercial & Industrial Materials. The Composites business manufactures products from glass-fiber reinforcements to meet diverse needs in a variety of high-performance composites markets. International Building Materials products – primarily roofing and insulation – are focused on making new and existing homes and buildings more energy efficient, comfortable, and attractive. CompoSiteS 3% Owens Corning reported sales of $5.2 billion in 2012 and employs approximately 15,000 people in 27 countries on five continents. Additional information is available at: 9% www.owenscorning.com. 26% SustainabiLity Owens Corning is committed to balancing economic growth with social 62% progress and environmental stewardship as it delivers sustainable solutions to its building materials and composites customers around the world. -

Acrylic Polymer Transparencies

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 4-1972 Acrylic Polymer Transparencies Inez Allen Kendrick Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Art Education Commons, Art Practice Commons, and the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kendrick, Inez Allen, "Acrylic Polymer Transparencies" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1554. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1553 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF T.HE THESIS OF Inez Allen Kendrick tor the Master ot Science in Teaching in Art presented April 26, 1972. TITLE: Acrylic Polymer Transparencies. APPROVED BY MEMBERS 01' 'lBE THESIS COMMITTEE: Richard J. ~asch, Chairman ~d B. Kimbrell Robert S. Morton Brief mentions by three writers on synthetic painting media first intrigued my interest in a' new technique of making transparent acrylic paintings on glass or plexiglas supports, some ot which were said to I I simulate stained-glass windows. In writing this paper on acrylic polymer'", transparencies, 'my problem was three-told: first. to determine whether any major recognized works of art have been produced by this, method; second, to experiment with the techni'que and materials in order to explore their possibilities for my own work; and third, to determine whether both materials and methods would be suitable for use in a classroom. -

6-Stained Glass in Lancaster

STAINED GLASS IN LANCASTER Lancaster Civic Society Leaflet 6 St Thomas, in Lancaster Priory by R.F. Ashmead of Abbott & Co (1966} The beauty of stained glass has been recognised since the Middle Ages and it is still popular. Lancaster had three notable stained-glass firms – Seward & Co, Shrigley & Hunt and Abbott & Co – which produced fine work from 1825 to 1996, relying on their artists and craftsmen. Their work The later nineteenth century was a good time for stained glass – new churches, hospitals, town halls, ocean liners, pubs and country houses – the firms’ work can be seen in all these. Shrigley and Hunt initially favoured a Pre-Raphaelite style, lighter in design and colour than its predecessors, strongly decorative, detailed, with realistic scenes and faces telling clear allegories and Biblical stories. Stronger colours were used in the 1880s. Their two main artists, Edward Holme Jewitt and Carl Almquist, had different styles, so widening the firm’s client base. They opened a studio in London to keep Almquist in the firm and to pick up on metropolitan shifts in taste. The firm also made decorative wall tiles. Abbott & Co followed these Late Victorian and Edwardian trends but also developed more modernist styles for interwar houses and in the 1960s. Both firms got contracts in association with the noted Lancaster architectural practice of Paley and Austin. Shrigley and Hunt used their London contacts to get work with Richard Norman Shaw and Alfred Waterhouse. Local magnates such as the Storeys and Williamsons of Lancaster and the brewing families of Boddington (Manchester) and Greenall (Warrington) also patronised them.