Mimicry, Biosemiotics, and the Animalhuman Binary in Thomas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karl Jordan: a Life in Systematics

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Kristin Renee Johnson for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of SciencePresented on July 21, 2003. Title: Karl Jordan: A Life in Systematics Abstract approved: Paul Lawrence Farber Karl Jordan (1861-1959) was an extraordinarily productive entomologist who influenced the development of systematics, entomology, and naturalists' theoretical framework as well as their practice. He has been a figure in existing accounts of the naturalist tradition between 1890 and 1940 that have defended the relative contribution of naturalists to the modem evolutionary synthesis. These accounts, while useful, have primarily examined the natural history of the period in view of how it led to developments in the 193 Os and 40s, removing pre-Synthesis naturalists like Jordan from their research programs, institutional contexts, and disciplinary homes, for the sake of synthesis narratives. This dissertation redresses this picture by examining a naturalist, who, although often cited as important in the synthesis, is more accurately viewed as a man working on the problems of an earlier period. This study examines the specific problems that concerned Jordan, as well as the dynamic institutional, international, theoretical and methodological context of entomology and natural history during his lifetime. It focuses upon how the context in which natural history has been done changed greatly during Jordan's life time, and discusses the role of these changes in both placing naturalists on the defensive among an array of new disciplines and attitudes in science, and providing them with new tools and justifications for doing natural history. One of the primary intents of this study is to demonstrate the many different motives and conditions through which naturalists came to and worked in natural history. -

OBITUARIES Sir Edward Poulton, F.R.S

No. 3870, jANUARY 1, 1944 NATURE 15 the University of Edinburgh, previously held by a tragic death, and his successor, F. Hasenohrl, was Black. To him we owe the discovery of the maximum killed in action on the Italian front in 1915. The density of water. The centenary of John Dalton falls chemists born in 1844 include Prof. J. Emerson on July 27 of this year, but any commemoration Reynolds (died 1920), who occupied for twenty-eight must inevitably be clouded over by the results of years the chair of chemistry in the University of the air raid of December 24, 1940, when the premises Dublin, and Ferdinand Hurter (died 1898), a native of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society of Schaffhausen, Switzerland, who came to England were completely destroyed. From 1817 until 1844 in 1867 and became principal chemist to the United DaJton was president of the Society, and within its Alkali Company. Among astronomers, Prof. W. R. walls he taught, lectured and experimented. The Brooks (died 1921) of the United States was famous Society had an unequalled collection of his apparatus, as a 'comet hunter'. Charles Trepied (died 1907) was but after digging among the ruins the only things for many years director of the Observatory at found were his gold watch, a spark eudiometer and Bouzariah, eleven kilometres from Algiers, while some charred remains of letters and note-books. A Annibale Ricco (died 1919), though he began life as month after Dalton passed away in Manchester, an engineer, for nineteen years directed the observa Francis Baily died in London, after a life devoted to tory of Catania and Etna, his special subject being astronomy and kindred subjects. -

Decontextualized Learning for Interpretable Hierarchical Representations of Visual Patterns

DECONTEXTUALIZED LEARNING FOR INTERPRETABLE HIERARCHICAL REPRESENTATIONS OF VISUAL PATTERNS ∗ R. Ian Etheredge1, 2, 3, , Manfred Schartl4, 5, 6, 7, and Alex Jordan1, 2, 3 1Department of Collective Behaviour, Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, Konstanz, Germany 2Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behaviour, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany 3Department of Biology, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany 4Centro de Investigaciones Científicas de las Huastecas Aguazarca, A.C., Calnali, Hidalgo, Mexico 5Developmental Biochemistry, Biocenter, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Bavaria, Germany 6Hagler Institute for Advanced Study, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA 7Xiphophorus Genetic Stock Center, Texas State University San Marcos, San Marcos, TX, USA September 22, 2020 SUMMARY Apart from discriminative models for classification and object detection tasks, the application of deep convolutional neural networks to basic research utilizing natural imaging data has been somewhat limited; particularly in cases where a set of interpretable features for downstream analysis is needed, a key requirement for many scientific investigations. We present an algorithm and training paradigm designed specifically to address this: decontextualized hierarchical representation learning (DHRL). By combining a generative model chaining procedure with a ladder network architecture and latent arXiv:2009.09893v1 [cs.CV] 31 Aug 2020 space regularization for inference, DHRL address the limitations of small datasets and encourages a disentangled set of hierarchically organized features. In addition to providing a tractable path for analyzing complex hierarchal patterns using variation inference, this approach is generative and can be directly combined with empirical and theoretical approaches. To highlight the extensibility and usefulness of DHRL, we demonstrate this method in application to a question from evolutionary biology. -

Orchiflora March 2014

Volume 4, Issue 6 Orchiflora March 2014 Announcements: Monthly General Meetings: 4th Wednes- day of each month (except July, August Speaker Series: & December) at Van Dusen Floral Hall March 26th, 2014: Calvin Wong: Cypripediums Doors Open 6:30pm, Meeting starts at April 23rd, 2014: Inge and Peter Poot: Stanhopeas and Coryanthes 7:30pm May 28th, 2014: Mario Ferussi: Masdevallias and Draculas Inside this issue: Culture class, held in the Cedar room, VanDusen Gardens from 6:30 to 8: 30 pm, all orchid related questions welcome Request for Orchids for Show! Pg 2 April 14, (Monday) 6:30 pm - 8:30 pm , Cedar Room, Van Dusen Gardens, 5251 Oak street: Forum on Paphiopedilums. Bring your expertise or your questions. We are open to any questions about any orchids, of course. Come Message From the President Pg 3 join this lively group and learn how to grow orchids. All levels of expertise welcome - we all began as beginners, at some time. May 12: Topic to be determined - give your suggestions! Show Schedule Pg 4 Upcoming shows: Members’ Showcase: Jim Poole Pg 5 Vancouver Orchid Society Show March 22-23, preview night Friday March 31, reserve your ticket ($12) by emailing [email protected] Monthly Show Table—26 Feb 2014 Pg 6 Central Vancouver Island Orchid Society Show, April 12-13, Nanaimo North Town Centre, 4750 Rutherford Road, Nanaimo, B.C. PNWJC Awards from 08 Feb 2014 Pg 9 Show Notes: We need your blooming orchids! February Meeting Minutes Pg 11 We will need your orchids for our VOS display. Grant Rampton will kindly coordinate our display, and it would be nice if he had an idea of how many plants are going to be available. -

Revista De Temas Nicaragüenses. Dedicada a La Investigación Sobre

No. 56 - Diciembre 2012 ISSN 2164-4268 TT E E M M A AS S NNI I C C A A R R A A G G Ü Ü E E N NS S E E S S una revista dedicada a documentar asuntos referentes a Nicaragua Contenido NUESTRA PORTADA.................................................................................................................................4 Homenaje al Dr. Salvador Mendieta Cascante .......................................................................................4 Flavio Rivera Montealegre..................................................................................................................4 Introducción a La enfermedad de Centroamérica.........................................................................................23 José Mejía Lacayo............................................................................................................................23 DEL ESCRITORIO DEL EDITOR......................................................................................................31 Nicaragua y la Ciencia en el Mundo.......................................................................................................31 ENSAYOS.......................................................................................................................................................34 Léxico Modernista en los Versos de Azul... (Octava Entrega)...........................................................34 Eduardo Zepeda-Henríquez.............................................................................................................34 -

Back Matter (PDF)

[ 229 • ] INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, S e r ie s B, FOR THE YEAR 1897 (YOL. 189). B. Bower (F. 0.). Studies in the Morphology of Spore-producing Members.— III. Marattiaceae, 35. C Cheirostrobus, a new Type of Fossil Cone (Scott), 1. E. Enamel, Tubular, in Marsupials and other Animals (Tomes), 107. F. Fossil Plants from Palaeozoic Rocks (Scott), 1, 83. L. Lycopodiaceae; Spencerites, a new Genus of Cones from Coal-measures (Scott), 83. 230 INDEX. M. Marattiaceae, Fossil and Recent, Comparison of Sori of (Bower), 3 Marsupials, Tubular Enamel a Class Character of (Tomes), 107. N. Naqada Race, Variation and Correlation of Skeleton in (Warren), 135 P. Pteridophyta: Cheirostrobus, a Fossil Cone, &c. (Scott), 1. S. Scott (D. H.). On the Structure and Affinities of Fossil Plants from the Palaeozoic Ro ks.—On Cheirostrobus, a new Type of Fossil Cone from the Lower Carboniferous Strata (Calciferous Sandstone Series), 1. Scott (D. H.). On the Structure and Affinities of Fossil Plants from the Palaeozoic Rocks.—II. On Spencerites, a new Genus of Lycopodiaceous Cones from the Coal-measures, founded on the Lepidodendron Spenceri of Williamson, 83. Skeleton, Human, Variation and Correlation of Parts of (Warren), 135. Sorus of JDancea, Kaulfxissia, M arattia, Angiopteris (Bower), 35. Spencerites insignis (Will.) and S. majusculus, n. sp., Lycopodiaceous Cones from Coal-measures (Scott), 83. Sphenophylleae, Affinities with Cheirostrobus, a Fossil Cone (Scott), 1. Spore-producing Members, Morphology of.—III. Marattiaceae (Bower), 35. Stereum lvirsutum, Biology of; destruction of Wood by (Ward), 123. T. Tomes (Charles S.). On the Development of Marsupial and other Tubular Enamels, with Notes upon the Development of Enamels in general, 107. -

Deceived by Orchids: Sex, Science, fiction and Darwin

BJHS 49(2): 205–229, June 2016. © British Society for the History of Science 2016 doi:10.1017/S0007087416000352 First published online 09 June 2016 Deceived by orchids: sex, science, fiction and Darwin JIM ENDERSBY* Abstract. Between 1916 and 1927, botanists in several countries independently resolved three problems that had mystified earlier naturalists – including Charles Darwin: how did the many species of orchid that did not produce nectar persuade insects to pollinate them? Why did some orchid flowers seem to mimic insects? And why should a native British orchid suffer ‘attacks’ from a bee? Half a century after Darwin’s death, these three mysteries were shown to be aspects of a phenomenon now known as pseudocopulation, whereby male insects are deceived into attempting to mate with the orchid’s flowers, which mimic female insects; the males then carry the flower’s pollen with them when they move on to try the next deceptive orchid. Early twentieth-century botanists were able to see what their predecessors had not because orchids (along with other plants) had undergone an imaginative re-creation: Darwin’s science was appropriated by popular interpreters of science, including the novelist Grant Allen; then H.G. Wells imagined orchids as killers (inspiring a number of imitators), to produce a genre of orchid stories that reflected significant cultural shifts, not least in the presentation of female sexuality. It was only after these changes that scientists were able to see plants as equipped with agency, actively able to pursue their own, cunning reproductive strategies – and to outwit animals in the process. -

The Biological Age of a Bloodstain Donor Author(S): Jack Ballantyne, Ph.D

The author(s) shown below used Federal funding provided by the U.S. Department of Justice to prepare the following resource: Document Title: The Biological Age of a Bloodstain Donor Author(s): Jack Ballantyne, Ph.D. Document Number: 251894 Date Received: July 2018 Award Number: 2009-DN-BX-K179 This resource has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. This resource is being made publically available through the Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. National Center for Forensic Science University of Central Florida P.O. Box 162367 · Orlando, FL 32826 Phone: 407.823.4041 Fax: 407.823.4042 Web site: http://www.ncfs.org/ Biological Evidence _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Biological Age of a Bloodstain Donor FINAL REPORT May 27, 2014 Department of Justice, National Institute of justice Award Number: 2009-DN-BX-K179 (1 October 2009 – 31 May 2014) _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Principal Investigator: Jack Ballantyne, PhD Professor Department of Chemistry Associate Director for Research National Center for Forensic Science P.O. Box 162367 Orlando, FL 32816-2366 Phone: (407) 823 4440 Fax: (407) 823 4042 e-mail: [email protected] 1 This resource was prepared by the author(s) using Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

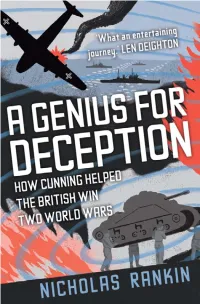

A Genius for Deception.Pdf

A Genius for Deception This page intentionally left blank A GENIUS FOR DECEPTION How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars nicholas rankin 1 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2008 by Nicholas Rankin First published in Great Britain as Churchill’s Wizards: The British Genius for Deception, 1914–1945 in 2008 by Faber and Faber, Ltd. First published in the United States in 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rankin, Nicholas, 1950– A genius for deception : how cunning helped the British win two world wars / Nicholas Rankin. p. cm. — (Churchill’s wizards) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-538704-9 1. Deception (Military science)—History—20th century. 2. World War, 1914–1918—Deception—Great Britain. 3. World War, 1939–1945—Deception—Great Britain. 4. Strategy—History—20th century. -

Extraocular Photoreception Mediates Adaptive Colour Change and 2 Background Choice Behaviour in Peppered Moth Caterpillars 3 Amy Eacock12†, Hannah M

1 1 Extraocular photoreception mediates adaptive colour change and 2 background choice behaviour in peppered moth caterpillars 3 Amy Eacock12†, Hannah M. Rowland2,3†, Arjen E. van’t Hof1, Carl J. Yung1, Nicola 4 Edmonds1 and Ilik J. Saccheri1* 5 1Institute of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, UK. 6 2Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, 07745 Jena, Germany. 7 3 Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge, CB2 3EJ, 8 UK. 9 †These authors contributed equally to this work. 10 *e-mail: [email protected] 11 Light sensing by tissues distinct from the eye occurs in diverse animal groups, enabling 12 circadian control and phototactic behaviour. Extraocular photoreceptors may also 13 facilitate rapid colour change in cephalopods and lizards, but little is known about the 14 sensory system that mediates slow colour change in arthropods. We previously reported 15 that slow colour change in twig-mimicking caterpillars of the peppered moth (Biston 16 betularia) is a response to achromatic and chromatic visual cues. Here we show that the 17 perception of these cues, and the resulting phenotypic responses, does not require ocular 18 vision. Caterpillars with completely obscured ocelli remained capable of enhancing their 19 crypsis by changing colour and choosing to rest on colour-matching twigs. A suite of 20 visual genes, expressed across the larval integument, likely plays a key role in the 21 mechanism. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that extraocular colour sensing 22 can mediate pigment-based colour change and behaviour in an arthropod. 23 Dermal photoreception, the ability to perceive photic information through the skin 24 independently of eyes, has evolved a number of times to serve a variety of functions 1-4. -

Geological Survey

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BULLETIN UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 3STo. 52 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1889 UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SUKVEY J. W. POWELL, DIRECTOE SUBAERIAL DECAY OF ROCKS OF THE RED COLOR OF BY WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1889 CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transmittal................ ..................................... 9 Introduction........ ............................... ~.... ................ 11 I. Subaerial decay of rocks .................................................... 12 Decay of the crystalline rocks of the Piedmont region.................... 12 Decay of the rocks of the Newark system................................ 15 Decay of the rocks of the southern Appalachians......................... 18 Decay of the rocks of the Great Appalachian Valley...................... 20 Absence of decayed rocks in the arid region of the Far West.............. 26 Subaerial decay in other countries ....................................... 28 Conditions favoring the decay of rocks............................ 1...... 30 Effects of geologically recent orographic movement on the distribution of residual deposits in the Appalachian region.......................... 34 The soluble portions of rocks............................................ 37 Characteristics of residual clays ......................................... 39 Economic products of residual clays ..................................... 43 II. Origin of the red color of certain formations ................................. 44 A hypothesis proposed ................................................. -

Introduction Adaptive Appearance in Nineteenth-Century Culture

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47759-8 — Mimicry and Display in Victorian Literary Culture Will Abberley Excerpt More Information Introduction Adaptive Appearance in Nineteenth-Century Culture Appearances matter. Thus contended the naturalist Henry Walter Bates in when he delivered a paper to the Linnean Society of London on curious patterns of resemblance among Amazonian flora and fauna. Bates had spent eleven years in the country studying animals (particularly insects) that took on the aspects of vegetation, terrain or other species. His interest in such resemblances ran against a growing tendency in science to disregard nature’s impressive qualities as superficial distractions. The emerging discourse of objectivity advocated mechanised methods of obser- vation supposedly purged of personal perceptions. The scalpel and micro- scope promised to pierce through illusions that tricked the casual eye. Yet, instead of expunging illusions from his evidence, Bates placed them centre- stage. ‘These imitative resemblances’, he wrote, ‘are full of interest, and fill us with the greater astonishment the closer we investigate them; for some show a minute and palpably intentional likeness which is perfectly stagger- ing’. Such appearances, Bates suggested, were not trivial but vital clues to evolutionary history. This point was demonstrated by the interspecies resemblances which Bates called mimicry. These resemblances seemed to occur when two species with common foes lived side by side and one possessed some defence such as a noxious taste. Bates argued that, as predators learned to avoid the defended species, they were also likely to avoid other creatures that resembled it. This dynamic created a selective pressure favouring the survival of individuals that imitated the model species to ever-greater degrees.