Creating Sound Pedagogy and Safe Spaces for Transgender Singers in the Horc Al Rehearsal Gerald Dorsey Gurss University of South Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soundtrack Walt Disney

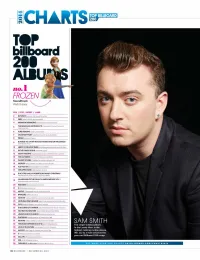

TOP BILLBOARD CHARTS200 TOP billboard 2011 ALB no.1 FROZEN Soundtrack Walt Disney POS / TITLE / ARTIST / LABEL 2 BEYONCEBeyonce Parkwood/Columbia 3 1989 TaylorSwilt Big Machine/BMW 4 MIDNIGHT MEMORIES OneOgrecuon SYCO/Columbia THE MARSHALL MAINERS LP 2 Emlnem Web/Shady/Aftermath/ Interscope/IGA 6 PURE HEROINE Lade Lava/Republic 7 CRASH MY PARTY Luke Bryan Capitol Nashville/UMGN 8 PRISM KutyPenyCapitol BLAME IT ALL ON MY ROOTS: FIVE DECADES OF INFLUENCES 9 Garth Brooks Pearl 10 HERE'S TOTHE GOODDMES RaidaGeogiaLine Republic Nastwille/BMLG 11 IN THE LONELY HOUR Sam Smith Capitol 12 NIGHT VISIONS imaginegragons KIDinaKORNER/interscope/IGA 13 THE OUTSIDERS Eric Church EMI Nashville/UPAGN 14 GHOST STORIES ColciplayParlophone/Atlantic/AG 15 NOW 50 Various Artists Sony Music/Universal/UMe 16 JUST AS I AM BrantleyGilben Valory/BMLG 17 WItAPPED IN RED KellyClarkson 19/RCA 18 DUCK THE HALLS:A ROBERTSON FAMILY CHRISIMAS TheRobertsons 4 Beards/EMI Nashville/UMGN GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: AWESOME MIX VOL.1 19 Soundtrack Marvel/Hollywood 20 PARTNERS Barbra Streisand Columbia 21 X EdSheeran Atlantic/AG 22 NATIVE OneRepublic Mosley/Interscope/IGA 23 BANGERZ MileyCyrus RCA 24 NOW 48Various Artists Sony Music/Universal/UMe 25 NOTHING WAS THE SAME Drake Young money/cash Money/Republic 26 GIRL Pharr,. amother/Columbia 27 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 5Seconds MummerHey Or Hi/Capitol 28 OLD BOOTS, NEW DIRT lasonAldean Broken Bow/BBMG 29 UNORTHODOX JUKEBOX Bruno Mars Atlantic/AG 30 PLATINUM Miranda Lambert RCA Nashville/SMN 31 NOW 49 VariousArtists Sony Music/Universal/UMe SAM SMITH 32 THE 20/20 EXPERIENa (2 OF 2) Justin Timberlake RCA The singer's debut album, 33 LOVE IN THE FUTURE lohnLegend G.O.O.D./Columbia In the Lonely Hour, is the 34 ARTPOPLadyGaga Streamline/Interscope/IGA highest-ranking rookie release 35 V Maroon5222/Interscope/IGA (No. -

183 Anti-Valentine's Day Songs (2015)

183 Anti-Valentine's Day Songs (2015) 4:24 Time Artist Album Theme Knowing Me Knowing You 4:02 Abba Gold Break up Lay All Your Love On Me 5:00 Abba Gold cautionary tale S.O.S. 3:23 Abba Gold heartbreak Winner Takes it All 4:55 Abba Gold Break up Someone Like You 4:45 Adele 21 Lost Love Turning Tables 4:08 Adele 21 broken heart Rolling in the Deep 3:54 Adlele 21 broken heart All Out Of Love 4:01 Air Supply Ulitimate Air Supply Lonely You Oughta Know 4:09 Alanis Morissette Jagged Little Pill broken heart Another heart calls 4:07 All American Rejects When the World Comes Down jerk Fallin' Apart 3:26 All American Rejects When the World Comes Down broken heart Gives You Hell 3:33 All American Rejects When the World Comes Down moving on Toxic Valentine 2:52 All Time Low Jennifer's Body broken heart I'm Outta Love 4:02 Anastacia Single giving up Complicated 4:05 Avril Lavigne Let Go heartbreak Good Lovin' Gone Bad 3:36 Bad Company Straight Shooter cautionary tale Able to Love (Sfaction Mix) 3:27 Benny Benassi & The Biz No Matter What You Do / Able to Love moving on Single Ladies (Put a Ring On It) 3:13 Beyonce I Am Sasha Fierce empowered The Best Thing I Never Had 4:14 Beyonce 4 moving on Love Burns 2:25 Black Rebel Motorcycle Club B.R.M.C. cautionary tale I'm Sorry, Baby But You Can't Stand In My Light Anymore 3:11 Bob Mould Life & Times moving on I Don't Wish You Were Dead Anymore 2:45 Bowling for Soup Sorry for Partyin' broken heart Love Drunk 3:47 Boys Like Girls Love Drunk cautionary tale Stronger 3:24 Britney Spears Opps!.. -

Treble Voices in Choral Music

loft is shown by the absence of the con• gregation: Bach and Maria Barbara were Treble Voices In Choral Music: only practicing and church was not even in session! WOMEN, MEN, BOYS, OR CASTRATI? There were certain places where wo• men were allowed to perform reltgious TIMOTHY MOUNT in a "Gloria" and "Credo" by Guillaume music: these were the convents, cloisters, Legrant in 1426. Giant choir books, large and religious schools for girls. Nuns were 2147 South Mallul, #5 enough for an entire chorus to see, were permitted to sing choral music (obvious• Anaheim, California 92802 first made in Italy in the middle and the ly, for high voices only) among them• second half of the 15th century. In selves and even for invited audiences. England, choral music began about 1430 This practice was established in the with the English polyphonic carol. Middle Ages when the music was limited Born in Princeton, New Jersey, Timo• to plainsong. Later, however, polyphonic thy Mount recently received his MA in Polyphonic choral music took its works were also performed. __ On his musi• choral conducting at California State cue from and developed out of the cal tour of Italy in 1770 Burney describes University, Fullerton, where he was a stu• Gregorian unison chorus; this ex• several conservatorios or music schools dent of Howard Swan. Undergraduate plains why the first choral music in Venice for girls. These schools must work was at the University of Michigan. occurs in the church and why secular not be confused with the vocational con• compositions are slow in taking up He has sung professionally with the opera servatories of today. -

The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians

The New GROVE Dictionary of Music and Musicians EDITED BY Stanley Sadie 12 Meares - M utis London, 1980 376 Moda Harold Powers Mode (from Lat. modus: 'measure', 'standard'; 'manner', 'way'). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term 'mode' has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and in this century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain pheno mena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see SOUND, §5. I. The term. II. Medieval modal theory. III. Modal theo ries and polyphonic music. IV. Modal scales and folk song melodies. V. Mode as a musicological concept. I. The term I. Mensural notation. 2. Interval. 3. Scale or melody type. I. MENSURAL NOTATION. In this context the term 'mode' has two applications. First, it refers in general to the proportional durational relationship between brevis and /onga: the modus is perfectus (sometimes major) when the relationship is 3: l, imperfectus (sometimes minor) when it is 2 : I. (The attributives major and minor are more properly used with modus to distinguish the rela tion of /onga to maxima from the relation of brevis to longa, respectively.) In the earliest stages of mensural notation, the so called Franconian notation, 'modus' designated one of five to seven fixed arrangements of longs and breves in particular rhythms, called by scholars rhythmic modes. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

The Ithacan, 1984-04-19

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1983-84 The thI acan: 1980/81 to 1989/90 4-19-1984 The thI acan, 1984-04-19 The thI acan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1983-84 Recommended Citation The thI acan, "The thI acan, 1984-04-19" (1984). The Ithacan, 1983-84. 22. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1983-84/22 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1980/81 to 1989/90 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1983-84 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. THE ITHACAN,·,,- 'Y',.o The Student Newspaper for Ithaca College ·, ;,,;i_\ ~ ,~ ~ ~, ' . ,;"y April 19, 1984 ..1\ · · · c\,,, Volume 15 Issue 11 ·:...,.., \ ,./ Ithaca College will''<>- increase• your tu1t1on• • by 8.5 percent rate Ithaca. NY--lthaca College tui principal rea~ons for the in tion will incwase S5:l6 10 crease c1rc acl<litional funds w S6.5(i2 for the 1984-85 quired for ..,,uctcnt financial aid. academic y!'ar. Coll1·g1· of fc1culty and staff salarws and ficials announcccl toclay, lwndits. ancl 1lw high co~, ot Standarcl room ancl hoard .,,,11e-of-1lw-,ir1 instrunional and student insurance will Ill· <·quipmenl cre,N· SWJ resulting 111 charges In spi11· ot IIH·s<· pressuws. of S2.992. rhe total 1984-85 sn1- 1.1ppinrn11 sc1ys lh,11 "llllaca·s den1 llill of S9.S54 rcprc-s1·n1s 1u11ion r1·m,1in~ qu11c an 8.58 pt•rc·<'nl lrl(TeclS(' 0\ er wasonablc. -

We Are Proud to Offer to You the Largest Catalog of Vocal Music in The

Dear Reader: We are proud to offer to you the largest catalog of vocal music in the world. It includes several thousand publications: classical,musical theatre, popular music, jazz,instructional publications, books,videos and DVDs. We feel sure that anyone who sings,no matter what the style of music, will find plenty of interesting and intriguing choices. Hal Leonard is distributor of several important publishers. The following have publications in the vocal catalog: Applause Books Associated Music Publishers Berklee Press Publications Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company Cherry Lane Music Company Creative Concepts DSCH Editions Durand E.B. Marks Music Editions Max Eschig Ricordi Editions Salabert G. Schirmer Sikorski Please take note on the contents page of some special features of the catalog: • Recent Vocal Publications – complete list of all titles released in 2001 and 2002, conveniently categorized for easy access • Index of Publications with Companion CDs – our ever expanding list of titles with recorded accompaniments • Copyright Guidelines for Music Teachers – get the facts about the laws in place that impact your life as a teacher and musician. We encourage you to visit our website: www.halleonard.com. From the main page,you can navigate to several other areas,including the Vocal page, which has updates about vocal publications. Searches for publications by title or composer are possible at the website. Complete table of contents can be found for many publications on the website. You may order any of the publications in this catalog from any music retailer. Our aim is always to serve the singers and teachers of the world in the very best way possible. -

Warren G, G-Spot (Feat

Warren G, G-Spot (feat. El DeBarge, Val Young) [Warren G] I'm the illest, what? I'm the illest, Warren G, uh yeah I'm the illest, the illest you've ever seen Haha check this shit out do' Peep game, look, hmm She used to tell me that she loved me all the time I turned to her, and say that I'm infatuated, concentrated on cuttin it up Body bustin out your blouse, don't button it up Me and you could make a getaway, up in the cut I'm just a squirrel in your world, bustin a nut Slide in the passenger side and creep to the tilt And maybe you could get a chance to sleep on my silk because you come with, that A-1 shit The kind I wouldn't mind havin a 20-year run with I'm done with these games, played by these dames I could exit the drama the same way that I came Cos I gotta put it down for my sons so you, skanless scuds gets none of my funds Cos I can't be in love with my pockets on fee Get the money, the power and the rest come for free, you know [Chorus: El DeBarge, (Val Young)] I let you hang (I let you hang around) so you could see (so that you, could see) You tried to switch (Understand, tryin to switch) the fool out of me (and make a fool, of me) I meant (So I guess I'll have to let you be) Baby (Baby baby baby baby you know) [repeat] [Warren G] Now baby, look at the time We gotta do what we gotta do The club's about to close, don't you wanna ride in a Rolls, Royce? Make it real moist Take the Rolls to the jet, take the jet to my yacht Letcha kick it for a week in my Carribbean spot Coconut milk bath (bath), private beach, first class (class) -

Sew What? Inc. Provided Stage Drapery for Grammy Winner Sam Smith’S in the Lonely Hour Tour LOS ANGELES AREA STAGE DRAPERY MANUFACTURER, SEW WHAT? INC

Sew What? Inc. Provided Stage Drapery for Grammy Winner Sam Smith’s In the Lonely Hour Tour LOS ANGELES AREA STAGE DRAPERY MANUFACTURER, SEW WHAT? INC. RECENTLY COMPLETED WORK WITH GRAMMY WINNER SAM Rancho Dominguez, CA SMITH AND HIS TEAM ON STAGE DRAPERY FOR February 18, 2015 SMITH’S SET IN THE LONELY HOUR TOUR. It has been a meteoric rise to the top for British singer and four Grammy winner, Sam Smith. The pop singer began his first arena headlining tour in North America in 2014. By year’s end, Smith found himself nominated for six coveted Grammy Awards, including Best New Artist, Record of the Year, Song of the Year and Best Pop Vocal Album. He ended up taking home all four of the mentioned Grammys. So few would disagree that British singer and songwriter Sam Smith is the current number one tour this season. Los Angeles area stage drapery manufacturer, Sew What? Inc. is also happy to have a small part in it, having recently worked with Smith’s team on their stage drapery used already for his In the Lonely Hour North American tour. In addition, Sew What? Inc. has something of a reputation as well. Megan Duckett, principal at Sew What? reported, "Sew What? was first contacted by Creative Director, Will Potts, as we have a good reputation in the industry and most designers are aware of who we are. " The drapery manufacturer worked on a stage set that was an original design by Will Potts. "Sew What have serviced my design very well, and even performed a top quality and efficient service extending overseas for pre production which was in the UK. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Research 5-8-2021 The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera Samuel Sherman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/honors Recommended Citation Sherman, Samuel, "The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 47. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/honors/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Northern Colorado Greeley, Colorado The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for Graduation with Honors Distinction and the Degree of Bachelor of Music Samuel W. Sherman School of Music May 2021 Signature Page The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera PREPARED BY: Samuel Sherman APPROVED BY THESIS ADVISOR: _ Brian Luedloff HONORS DEPT LIAISON:_ Dr. Michael Oravitz HONORS DIRECTIOR: Loree Crow RECEIVED BY THE UNIVERSTIY THESIS/CAPSONTE PROJECT COMMITTEE ON: May 8th, 2021 1 Abstract Opera, as an art form and historical vocal practice, continues to be a field where self-expression and the representation of the human experience can be portrayed. However, in contrast to the current societal expansion of diversity and inclusion movements, vocal range classifications within vocal music and its use in opera are arguably exclusive in nature. -

Jay Graydon Discography (Valid July 10, 2008)

Jay Graydon Discography (valid July 10, 2008) Jay Graydon Discography - A (After The Love Has Gone) Adeline 2008 RCI Music Pro ??? Songwriter SHE'S SINGIN' HIS SONG (I Can Wait Forever) Producer 1984 258 720 Air Supply GHOSTBUSTERS (Original Movie Soundtrack) Arista Songwriter 1990 8246 Engineer (I Can Wait Forever) Producer 2005 Collectables 8436 Air Supply GHOSTBUSTERS (Original Movie Soundtrack - Reissue) Songwriter 2006 Arista/Legacy 75985 Engineer (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply DEFINITIVE COLLECTION 1999 ARISTA 14611 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply ULTIMATE COLLECTION: MILLENNIUM [IMPORT] 2002 Korea? ??? Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) BMG Entertainment 97903 Producer Air Supply FOREVER LOVE 2003 BMG Entertainment, Argentina 74321979032 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) FOREVER LOVE - 36 GREATEST Producer Air Supply HITS 1980 - 2001 2003 BMG Victor BVCM-37408 Import (2 CDs) Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply PLATINUM & GOLD COLLECTION 2004 BMG Heritage 59262 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply LOVE SONGS 2005 Arista 66934 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply 2006 Sony Bmg Music, UK 82876756722 COLLECTIONS Songwriter Air Supply (I Can Wait Forever) 2006 Arista 75985 Producer GHOSTBUSTERS - (bonus track) remastered UPC: 828767598529 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply 2007 ??? ??? GRANDI SUCCESSI (2 CD) Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) ULTIMATE COLLECTION Producer Air Supply 2007 Sony/Bmg Import ??? [IMPORT] [EXPLICIT LYRICS] [ENHANCED] Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply ??? ??? ??? BELOVED Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply CF TOP 20 VOL.3 ??? ??? ??? Songwriter (Compilation by various artists) (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply COLLECTIONS TO EVELYN VOL.