Transformation of the Column Order in the Baroque Architecture in St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

The Architectural Style of Bay Pines VAMC

The Architectural Style of Bay Pines VAMC Lauren Webb July 2011 The architectural style of the original buildings at Bay Pines VA Medical Center is most often described as “Mediterranean Revival,” “Neo-Baroque,” or—somewhat rarely—“Churrigueresque.” However, with the shortage of similar buildings in the surrounding area and the chronological distance between the facility’s 1933 construction and Baroque’s popularity in the 17th and 18th centuries, it is often wondered how such a style came to be chosen for Bay Pines. This paper is an attempt to first, briefly explain the Baroque and Churrigueresque styles in Spain and Spanish America, second, outline the renewal of Spanish-inspired architecture in North American during the early 20th century, and finally, indicate some of the characteristics in the original buildings which mark Bay Pines as a Spanish Baroque- inspired building. The Spanish Baroque and Churrigueresque The Baroque style can be succinctly defined as “a style of artistic expression prevalent especially in the 17th century that is marked by use of complex forms, bold ornamentation, and the juxtaposition of contrasting elements.” But the beauty of these contrasting elements can be traced over centuries, particularly for the Spanish Baroque, through the evolution of design and the input of various cultures living in and interacting with Spain over that time. Much of the ornamentation of the Spanish Baroque can be traced as far back as the twelfth century, when Moorish and Arabesque design dominated the architectural scene, often referred to as the Mudéjar style. During the time of relative peace between Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Spain— the Convivencia—these Arabic designs were incorporated into synagogues and cathedrals, along with mosques. -

The Two-Piece Corinthian Capital and the Working Practice of Greek and Roman Masons

The two-piece Corinthian capital and the working practice of Greek and Roman masons Seth G. Bernard This paper is a first attempt to understand a particular feature of the Corinthian order: the fashioning of a single capital out of two separate blocks of stone (fig. 1).1 This is a detail of a detail, a single element of one of the most richly decorated of all Classical architec- tural orders. Indeed, the Corinthian order and the capitals in particular have been a mod- ern topic of interest since Palladio, which is to say, for a very long time. Already prior to the Second World War, Luigi Crema (1938) sug- gested the utility of the creation of a scholarly corpus of capitals in the Greco-Roman Mediter- ranean, and especially since the 1970s, the out- flow of scholarly articles and monographs on the subject has continued without pause. The basis for the majority of this work has beenformal criteria: discussion of the Corinthian capital has restedabove all onstyle and carving technique, on the mathematical proportional relationships of the capital’s design, and on analysis of the various carved components. Much of this work carries on the tradition of the Italian art critic Giovanni Morelli whereby a class of object may be reduced to an aggregation of details and elements of Fig. 1: A two-piece Corinthian capital. which, once collected and sorted, can help to de- Flavian period repairs to structures related to termine workshop attributions, regional varia- it on the west side of the Forum in Rome, tions,and ultimatelychronological progressions.2 second half of the first century CE (photo by author). -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

Hellenistic Greek Temples and Sanctuaries

Hellenistic Greek Temples and Sanctuaries Late 4th centuries – 1st centuries BC Other Themes: - Corinthian Order - Dramatic Interiors - Didactic tradition The «Corinthian Order» The «Normalkapitelle» is just the standardization Epidauros’ Capital (prevalent in Roman times) whose origins lays in (The cauliculus is still not the Epudaros’ tholos. However during the present but volutes and Hellenistic period there were multiple versions of helixes are in the right the Corinthian capital. position) Bassae 1830 drawing So-Called Today the capital is “Normal Corinthian Capital», no preserved compared to Basse «Evolution» (???) of the Corinthian capital Choragic Monument of Lysikrates in Athens Late 4th Century BC First istance of Corinthian order used outside. Athens, Agora Temple of Olympian Zeus. FIRST PHASE. An earlier temple had stood there, constructed by the tyrant Peisistratus around 550 BC. The building was demolished after the death of Peisistratos and the construction of a colossal new Temple of Olympian Zeus was begun around 520 BC by his sons, Hippias and Hipparchos. The work was abandoned when the tyranny was overthrown and Hippias was expelled in 510 BC. Only the platform and some elements of the columns had been completed by this point, and the temple remained in this state for 336 years. The work was abandoned when the tyranny was overthrown and Hippias was expelled in 510 BC. Only the platform and some elements of the columns had been completed by this point, and the temple remained in this state for 336 years. SECOND PHASE (HELLENISTIC). It was not until 174 BC that the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who presented himself as the earthly embodiment of Zeus, revived the project and placed the Roman architect Decimus Cossutius in charge. -

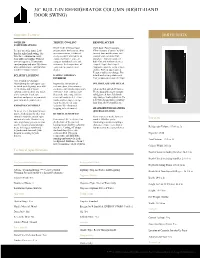

30” Built-In Refrigerator Column (Right-Hand Door Swing)

30” BUILT-IN REFRIGERATOR COLUMN (RIGHT-HAND DOOR SWING) Signature Features JBRFR30IGX OVER 250 TRINITY COOLING REMOTE ACCESS CONFIGURATIONS Revel in the trinity of food Open door. Power outages. Freezer or refrigerator. Left- preservation: three zones, three Filter changes. Connect to WiFi hand or right-hand swing. One, precision sensors, calibrated for real-time notifications and two, three columns in a row. every second. Fortified by an control your columns from Four different widths. With 12 exposed air tower, you can anywhere. Tap and swipe on one-unit options, 75 two-unit conquer humidity levels and both iOS and Android devices. combinations and over 250 three- customize the temperature of <sup>1</sup><br><sup>1 unit combinations, configuration each zone to your deepest Appliance must be set to remote is where bespoke begins. desires. enable. WiFi & app required. Features subject to change. For ECLIPTIC LIGHTING DARING OBSIDIAN details and privacy statement, INTERIOR visit jennair.com/connect.</sup> Live beyond the shadow. Abandoning the dark spots cast Inspired by the beauty of SOLID GLASS AND METAL by dated puck lighting, over 650 volcanic glass, this industry- LEDs frame and fill your exclusive dark finish erupts with All-metal bin and shelf frames. column, coming alive at a touch reflective, high-contrast style. Thick, naturally odor-resistant of the controls. Each zone Reject the unfeeling, lifeless solid glass. A forcefield at the awakens and pulses as you mold vessel of harsh steel. Let fine edge that prevents spillovers. To your column to your desires. foods and beverages emerge hell with cheap plastic in luxury from the interior of your door bins, shelves and liners. -

Baroque & Modern Expression

HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURAL THEORY, 48-311, Fall 2016 Prof. Gutschow, Week #4 Week #4: BAROQUE & MODERN EXPRESSION Tu./Th. Sept. 20/22 Required Readings for all Students: * H.F. Mallgrave, Architectural Theory: Vol.1: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 1870 (2006), pp.48-55, 57-117, 223-248. Focus especially on readings #29,31,32,34,35,37,39,40,92,94,99,100. Questions to think about: In your reading of the many excerpts associated with the Baroque, attempt to get an overview of how the Baroque period and mood is different than the Renaissance. What was the “battle of the ancients & moderns,” and who were the main players? How does the architectural theory conversation in France compare to that in England? What is “Palladianism,” and how does it relate to the “Baroque”? How does garden design start to skew the theoretical trajectory in England? What is “the picturesque”? * Perrault, C. Ordonnance for the Five Kinds of Columns after the Method of the Ancients = Ordonnances des Cinq Espèces de Colonne, intro. A. Pérez-Gómez (1683, 1993) pp.47-63, 65-66, 94-95, 153-154, skim155-175 Questions to think about: What are “Postive” and “Arbitrary” beauty? Which does Perrault favor? Why? What is Perrault’s attitude towards the “ancients”? How do Perrault’s Baroque ideas challenge Vitruvius and Renaissance architectural theory? Assigned/Other Readings: Questions to think about for all readings: What attributes does each author give to the Baroque, as opposed to the Renaissance? What theory does the author propose for why the Baroque evolved out of the Renaissance? How are the theoretical books and works of the Baroque different than the “treatises” of the Renaissance? Wölfflin, Heinrich. -

Architecture (ARCH) 1

Architecture (ARCH) 1 their architectural use. ARCH 504 Materials and Building Construction ARCHITECTURE (ARCH) II (3) This first-year graduate seminar course will continue to present students with information on fundamental and advanced building ARCH 501: Analysis of Architectural Precedents: Ancient Industrial materials and systems and on construction technologies associated with Revolution their architectural use. Students will also consider the advancements in architectural materials and technologies. It is the second part of 3 Credits a two-semester sequence preceded by ARCH 503. Recurrent course Analysis of architectural precendents from antiquity to the turn of the themes include 1) architecture as a product of culture (wisdom, abilities, twentieth century through methodologies emphasizing research and aspirations), 2) architecture as a product of place (materials, tools, critical inquiry. The 20th century Italian architectural historian and topography, climate), the relationship between architectural appearance theorist Manfredo Tafuri argued that architecture was intrinsically presented and the mode of construction employed, 3) materials and forward-looking and utopian: "project" in both the sense of "a design making as an expression of an idea and 4) the relationship of a building project" and a leap into the future, like "projectile" or "projection." However, whole to a detail. This course is motivated by these concerns: a firm he also argued that architectural history, understood deeply and critically, belief that architects -

The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance

•••••••• ••• •• • .. • ••••---• • • - • • ••••••• •• ••••••••• • •• ••• ••• •• • •••• .... ••• .. .. • .. •• • • .. ••••••••••••••• .. eo__,_.. _ ••,., .... • • •••••• ..... •••••• .. ••••• •-.• . PETER MlJRRAY . 0 • •-•• • • • •• • • • • • •• 0 ., • • • ...... ... • • , .,.._, • • , - _,._•- •• • •OH • • • u • o H ·o ,o ,.,,,. • . , ........,__ I- .,- --, - Bo&ton Public ~ BoeMft; MA 02111 The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance ... ... .. \ .- "' ~ - .· .., , #!ft . l . ,."- , .• ~ I' .; ... ..__ \ ... : ,. , ' l '~,, , . \ f I • ' L , , I ,, ~ ', • • L • '. • , I - I 11 •. -... \' I • ' j I • , • t l ' ·n I ' ' . • • \• \\i• _I >-. ' • - - . -, - •• ·- .J .. '- - ... ¥4 "- '"' I Pcrc1·'· , . The co11I 1~, bv, Glacou10 t l t.:• lla l'on.1 ,111d 1 ll01nc\ S t 1, XX \)O l)on1c111c. o Ponrnna. • The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance New Revised Edition Peter Murray 202 illustrations Schocken Books · New York • For M.D. H~ Teacher and Prie11d For the seamd edillo11 .I ltrwe f(!U,riucu cerurir, passtJgts-,wwbly thOS<' on St Ptter's awl 011 Pnlladfo~ clmrdses---mul I lr,rvl' takeu rhe t>pportrmil)' to itJcorporate m'1U)1 corrt·ctfons suggeSLed to nu.• byfriet1ds mu! re11iewers. T'he publishers lwvc allowed mr to ddd several nt•w illusrra,fons, and I slumld like 10 rltank .1\ Ir A,firlwd I Vlu,.e/trJOr h,'s /Jelp wft/J rhe~e. 711f 1,pporrrm,ty /t,,s 11/so bee,r ft1ke,; Jo rrv,se rhe Biblfogmpl,y. Fc>r t/Jis third edUfor, many r,l(lre s1m1II cluu~J!eS lwvi: been m"de a,,_d the Biblio,~raphy has (IJICt more hN!tl extet1si11ely revised dtul brought up to date berause there has l,een mt e,wrmc>uJ incretlJl' ;,, i111eres1 in lt.1lim, ,1rrhi1ea1JrP sittr<• 1963,. wlte-,r 11,is book was firs, publi$hed. It sh<>uld be 110/NI that I haw consistc11tl)' used t/1cj<>rm, 1./251JO and 1./25-30 to 111e,w,.firs1, 'at some poiHI betwt.·en 1-125 nnd 1430', .md, .stamd, 'begi,miug ilJ 1425 and rnding in 14.10'. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents Eight Elements of Home Office Design 11 Home Office Furniture Ideas 15 - 57 Drawer Systems & Hinges 58 - 59 Folding & Sliding Door Systems 60 - 61 Further Products 62 - 63 www.hettich.com 3 How will we work in the future? This is an exciting question what we are working on intensively. The fact is that not only megatrends, but also extraordinary events such as a pandemic are changing the world and influencing us in all areas of life. In the long term, the way we live, act and furnish ourselves will change. The megatrend Work Evolution is being felt much more intensively and quickly. www.hettich.com 5 Work Evolution Goodbye performance society. Artificial intelligence based on innovative machines will relieve us of a lot of work in the future and even do better than we do. But what do we do then? That’s a good question, because it puts us right in the middle of a fundamental change in the world of work. The creative economy is on the advance and with it the potential development of each individual. Instead of a meritocracy, the focus is shifting to an orientation towards the strengths and abilities of the individual. New fields of work require a new, flexible working environment and the work-life balance is becoming more important. www.hettich.com 7 Visualizing a Scenario Imagine, your office chair is your couch and your commute is the length of your hallway. Your snack drawer is your entire pantry. Do you think it’s a dream? No! Since work-from-home is very a reality these days due to the pandemic crisis 2020.