The Last Flight of Beaufort L.9808, Which Crashed Near R.A.F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanctuary Magazine Which Exemplary Sustainability Work Carried Westdown Camp Historic Environments, Access, Planning and Defence

THE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE SUSTAINABILITY MAGAZINE Number 43 • 2014 THE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE SUSTAINABILITY MAGAZINE OF DEFENCE SUSTAINABILITY THE MINISTRY MOD celebrates thirty years of conserving owls and raptors on Salisbury Plain Climate change adaptation Number 43 • 2014 and resilience on the MOD estate Spend 2 Save switch on the success CONTACTS Foreword by Jonathan Slater Director General Head Office and Defence Infrastructure SD Energy, Utilities & Editor Commissioning Services Organisation Sustainability Team Iain Perkins DIO manages the MOD’s property The SD EUS team is responsible for Energy Hannah Mintram It has been another successful year infrastructure and ensures strategic Management, Energy Delivery and Payment, for the Sanctuary Awards with judges management of the Defence estate as a along with Water and Waste Policy whole, optimising investment and Implementation and Data across the MOD Designed by having to choose between some very providing the best support possible to estate both in the UK and Overseas. Aspire Defence Services Ltd impressive entries. I am delighted to the military. Multi Media Centre see that the Silver Otter trophy has Energy Management Team Secretariat maintains the long-term strategy Tel: 0121 311 2017 been awarded to the Owl and Raptor for the estate and develops policy on estate Editorial Board Nest Box Project on Salisbury Plain. management issues. It is the policy lead for Energy Delivery and Payment Team Julia Powell (Chair) This project has been running for sustainable estate. Tel: 0121 311 3854 Richard Brooks more than three decades and is still Water and Waste Policy Implementation thriving thanks to the huge Operational Development and Data Team Editorial Contact dedication of its team of volunteers. -

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

Military Aircraft Crash Sites in South-West Wales

MILITARY AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES IN SOUTH-WEST WALES Aircraft crashed on Borth beach, shown on RAF aerial photograph 1940 Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For Cadw DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO. 2012/5 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO. 105344 DAT 115C Mawrth 2013 March 2013 MILITARY AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES IN SOUTH- WEST WALES Gan / By Felicity Sage, Marion Page & Alice Pyper Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Gwefan: www.archaeolegdyfed.org.uk Website: www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. 1198990) and a Registered Charity (No. 504616) CADEIRYDD CHAIRMAN: Prof. B C Burnham. CYFARWYDDWR DIRECTOR: K MURPHY BA MIFA SUMMARY Discussions amongst the 20th century military structures working group identified a lack of information on military aircraft crash sites in Wales, and various threats had been identified to what is a vulnerable and significant body of evidence which affect all parts of Wales. -

Editor Dino Carrara Visited RAF Leuchars to Hear How the RAF's Most Recent Front-Line Squadron to Be Equipped with the T

1(FIGHTER) SQUADRON’S NEW ERA Editor Dino Carrara visited RAF Leuchars to hear how the RAF’s most recent front-line squadron Above: The Officer Commanding 1(F) to be equipped Squadron, Wg Cdr Mark Flewin. RAF/MOD Crown Copyright 2012 - SAC Helen Rimmer with the Typhoon Left: RAF Leuchars’ two Typhoon units, 1(F) and 6 Squadrons, share the QRA has achieved a commitment at the base. Sometimes they also come together for deployments, such as the joint detachment to Exercise lot in a short Red Flag. These two Typhoons, one from each squadron, are shown over the space of time. HAS site used by 1(F) Sqn at Leuchars. Geoffrey Lee/Planefocus n September 15, 2012 the RAF’s 1(Fighter) Squadron re- from the facilities and ramp of the co-located unit. Then on January 7, However, it wasn’t long before the squadron was expanding its horizons Programme [TLP, run by ten NATO air forces and held at Albacete Air formed flying the Eurofighter Typhoon at RAF Leuchars in 2013 it moved to the hardened aircraft shelter (HAS) complex on the and taking part in an Advanced Tactical Leadership Course (ATLC) in Base in Spain] because of the number of assets that are available in Fife during the base’s airshow. The squadron’s last mount south-east corner of the airfield, previously used by the Tornado F3s November 2012 at Al Dhafra Air Base in the United Arab Emirates, whilst theatre and the diversity of air assets involved. Having a lot of aircraft in Owas the Harrier GR9 with which it flew its final sortie from of 111(F) Sqn. -

The Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force in Anti-Submarine Warfare Policy, 1918-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE ROYAL NAVY AND THE ROYAL AIR FORCE IN ANTI-SUBMARINE WARFARE POLICY, 1918-1945. By JAMES NEATE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the roles played by the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force in the formulation of Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) policy from 1918 to 1945. Its focus is on policy relating to the use of air power, specifically fixed-wing shore-based aircraft, against submarines. After a period of neglect between the Wars, airborne ASW would be pragmatically prioritised during the Second World War, only to return to a lower priority as the debates which had stymied its earlier development continued. Although the intense rivalry between the RAF and RN was the principal influence on ASW policy, other factors besides Service culture also had significant impacts. -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

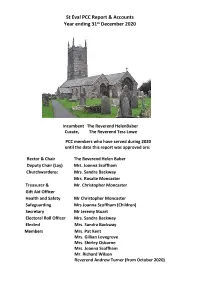

St Eval PCC Report & Accounts Year Ending 31St December 2020

St Eval PCC Report & Accounts Year ending 31st December 2020 Incumbent The Reverend HelenBaber Curate, The Reverend Tess Lowe PCC members who have served during 2020 until the date this report was approved are: Rector & Chair The Reverend Helen Baber Deputy Chair (Lay) Mrs. Joanna Scoffham Churchwardens: Mrs. Sandra Backway Mrs. Rosalie Moncaster Treasurer & Mr. Christopher Moncaster Gift Aid Officer Health and Safety Mr Christopher Moncaster Safeguarding Mrs Joanna Scoffham (Children) Secretary Mr Jeremy Stuart Electoral Roll Officer Mrs. Sandra Backway Elected Mrs. Sandra Backway Members Mrs. Pat Kent Mrs. Gillian Lovegrove Mrs. Shirley Osborne Mrs. Joanna Scoffham Mr. Richard Wilson Reverend Andrew Turner (from October 2020) The method of appointment of PCC members is set out in the Church Representation Rules. All church Attendees are encouraged to register on the Electoral Roll and stand for election to the PCC. The PCC met twice during the year. St. Eval PCC has the responsibility of co-operating with the incumbent in promoting the whole mission of the church, pastoral, evangelistic, social and ecumenical in the ecclesiastical parish. It also has maintenance responsibilities for the church, churchyard, church room, toilet block and grounds. The Parochial Church Council (PCC) is a charity excepted from registration with the Charity Commission. The church is part of the Diocese of Truro within the Church of England and is one of the four churches in the Lann Pydar Benefice. The other Parishes are St. Columb Major, St. Ervan and St. Mawgan-in-Pydar. The Parish Office, which is shared with the other 3 churches within the benefice, has now been relocated to the Rectory in St Columb Major. -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

Cliffs of Dover Blenheim

BRISTOL BLENHEIM IV GUIDE BY CHUCK 1 (Unit) SPITFIRE HURRICANE BLENHEIM TIGER MOTH BF.109 BF.110 JU-87B-2 JU-88 HE-111 G.50 BR.20M Mk Ia 100 oct Mk IA Rotol 100oct Mk IV DH.82 E-4 C-7 STUKA A-1 H-2 SERIE II TEMPERATURES Water Rad Min Deg C 60 60 - - 40 60 38 40 38 - - Max 115 115 100 90 95 90 95 Oil Rad (OUTBOUND) Min Deg C 40 40 40 - 40 40 30 40 35 50 50 Max 95 95 85 105 85 95 80 95 90 90 Cylinder Head Temp Min Deg C - - 100 - - - - - - 140 140 Max 235 240 240 ENGINE SETTINGS Takeoff RPM RPM 3000 3000 2600 FINE 2350 2400 2400 2300 2400 2400 2520 2200 Takeoff Manifold Pressure UK: PSI +6 +6 +9 BCO ON See 1.3 1.3 1.35 1.35 1.35 890 820 BCO ON GER: ATA ITA: mm HG RPM Gauge • BLABLALBLABClimb RPM RPM 2700 2700 2400 COARSE 2100 2300 2300 2300 2300 2300 2400 2100 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX Climb Manifold Pressure UK: PSI +6 +6 +5 See 1.23 1.2 1.15 1.15 1.15 700 740 GER: ATA ITA: mm HG RPM Gauge Normal Operation/Cruise RPM 2700 2600 2400 COARSE 2000 2200 2200 2200 2100 2200 2100 2100 RPM Normal Operation/Cruise UK: PSI +3 +4 +3.5 See 1.15 1.15 1.1 1.1 1.10 590 670 GER: ATA Manifold Pressure ITA: mm HG RPM Gauge Combat RPM RPM 2800 2800 2400 COARSE 2100 2400 2400 2300 2300 2300 2400 2100 Combat Manifold Pressure UK: PSI +6 +6 +5 See 1.3 1.3 1.15 1.15 1.15 700 740 GER: ATA ITA: mm HG RPM Gauge 5 min MAX 5 min MAX Emergency Power/ Boost RPM 2850 2850 2600 COARSE 2350 2500 2400 2300 2400 2400 2520 2200 RPM @ km 5 min MAX 5 min MAX 5 min MAX 1 min MAX 5 min MAX 1 min MAX 1 min MAX 1 min MAX 3 min -

Song of the Beauforts

Song of the Beauforts Song of the Beauforts No 100 SQUADRON RAAF AND BEAUFORT BOMBER OPERATIONS SECOND EDITION Colin M. King Air Power Development Centre © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Approval has been received from the owners where appropriate for their material to be reproduced in this work. Copyright for all photographs and illustrations is held by the individuals or organisations as identified in the List of Illustrations. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release, distribution unlimited. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. First published 2004 Second edition 2008 Published by the Air Power Development Centre National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: King, Colin M. Title: Song of the Beauforts : No 100 Squadron RAAF and the Beaufort bomber operations / author, Colin M. King. Edition: 2nd ed. Publisher: Tuggeranong, A.C.T. : Air Power Development Centre, 2007. ISBN: 9781920800246 (pbk.) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Beaufort (Bomber)--History. Bombers--Australia--History World War, 1939-1945--Aerial operations, Australian--History.