Digital Access Across Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Theoretical and Empirical Study of Social Media As a Crisis Communication Channel in the Aftermath of the BP Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Ill

A Theoretical and Empirical Study of Social Media as a Crisis Communication Channel in the Aftermath of the BP Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill ill By Kylie Ann Dowthwaite Date: 15 April 2011 University: Copenhagen Business School Masters: Cand.merc. MCM External Councilor: Nicolaj Hoejer Nielsen No. of pages: 81 STU: 184.127 Kylie Ann Dowthwaite | April 2011 Acknowledgement Several people have contributed to this research throughout the study period and thereby helped me to carry out this work. First of all I would like to thank my supervisor Nicolaj Hoejer Nielsen for his comments and support throughout my master thesis. I would also like to thank all the key informants and survey respondents for their cooperation and contribution to the work. Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to my fiancée, family and friends for their support and encouragement through the whole study period. Kylie Ann Dowthwaite Kylie Ann Dowthwaite | April 2011 Executive Summary On the 20th of April 2010 the largest oil spill in the history of the US occurred and BP was the main responsible party. This lead to a massive crisis communication effort, where multiple organisations were involved and social media was utilized on a scale never seen before in BP. Within classical crisis communication the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT), by Coombs, states that an appropriate response strategy has to be chosen depending on the crisis responsibility of the organisation. In the field of crisis communication for social media the theoretical framework is sporadic and very operational with Gonzalez-Herrero & Smith and Conway et al. -

OIG 13-A-08 Independent Evaluation of NRC's Use and Security of Social

EVALUATION REPORT Independent Evaluation of NRC’s Use and Security of Social Media OIG-13-A-08 January 23, 2013 All publicly available OIG reports (including this report) are accessible through NRC’s Web site at: http:/www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/insp-gen/ UNITED STATES NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20555-0001 OFFICE OF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL January 23, 2013 MEMORANDUM TO: R. William Borchardt Executive Director for Operations FROM: Stephen D. Dingbaum /RA/ Assistant Inspector General for Audits SUBJECT: INDEPENDENT EVALUATION OF NRC’S USE AND SECURITY OF SOCIAL MEDIA (OIG-13-A-08) Attached is the Office of the Inspector General’s (OIG) independent evaluation report titled, Independent Evaluation of NRC’s Use and Security of Social Media (OIG-13-A-08). The report presents the results of the subject evaluation. Agency comments provided during a December 7, 2012, exit conference have been incorporated, as appropriate, into this report. Please provide information on actions taken or planned on the recommendations within 30 days of the date of this memorandum. Actions taken or planned are subject to OIG followup as stated in Management Directive 6.1. We appreciate the cooperation extended to us by members of your staff during the evaluation. If you have any questions or comments about our report, please contact me at 415-5915 or Beth Serepca, Team Leader, at 415-5911. Attachment: As stated CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... IV AGENCY COMMENTS ..................................................................................... VIII CHAPTER 1: SOCIAL MEDIA MEASUREMENT .................................................. 1 NRC Narrowly Defines Social Media Success .................................................. 1 NRC Has made Progress Against All its Social Media Objectives ................... -

Indigenous Connections and Social Media: Māori Involvement in the Events at Standing Rock

Indigenous Connections and Social Media: Māori Involvement in the Events at Standing Rock India Fremaux A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Communication Studies (MCS) 2019 School of Communication Studies, Faculty of Design and Creative Technologies Abstract The whirlwind development of digital ICTs has had significant implications for Indigenous peoples and their movements towards social and political change. Digital ICTs facilitate global Indigenous connections, assist the rapid diffusion of information and present a decentralised outlet for Indigenous perspectives. However, for Indigenous groups, issues of access, cultural appropriation and misrepresentation remain. With the aid of digital ICTs, the Standing Rock movement successfully united Indigenous cultures across the world. This research focuses on Māori in Aotearoa (New Zealand) who expressed passionate support on social media and even travelled thousands of kilometres to stand in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux. The aim of this study is to determine the interest and involvement of Māori in these events via the qualitative analysis of two data sets drawn from participants; in-depth interviews and personal social media posts. Each participant was chosen for their vociferous support of the Standing Rock movement and their identification as Māori. The findings revealed that while participant interest stemmed from a number of areas, particularly pertaining to Indigenous affinity and kinship, it was social media that initiated and sustained that interest. These results indicate that there are deep connections between Māori and the Standing Rock Sioux and the role of social media in facilitating and maintaining those connections was complex. -

Final Thesis

University of Huddersfield Repository Penni, Janice The Online Evolution of Social Media: An Extensive Exploration of a Technological Phenomenomen and its Extended Use in Various Activities Original Citation Penni, Janice (2015) The Online Evolution of Social Media: An Extensive Exploration of a Technological Phenomenomen and its Extended Use in Various Activities. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/28332/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE ONLINE EVOLUTION OF SOCIAL MEDIA: AN EXTENSIVE EXPLORATION OF A TECHNOLOGICAL PHENOMENOMEN AND ITS EXTENDED USE IN VARIOUS ACTIVITIES By Janice F.Y. Penni A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER by Research In THE SCHOOL OF COMPUTING AND ENGINEERING STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF HUDDERSFIELD April 2015 © Janice Penni, 2015 Abstract The rise and popularity of Social media technologies has created an interactive and communicative global phenomenon that has enabled billions of users to connect to other individuals to not just Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn; but also with media sharing platforms such as Instagram and Pinterest. -

Enhancing Current Feedback Processes Through Social Media

Enhancing Current Feedback Processes through Social Media Monitoring An exploratory study of Social Media and Social Media monitoring practices within an MNC looking to combine new practices with traditional customer-centric processes. Author(s): Fredrik Bergstrand, Tutor: Professor Hans Jansson Growth Through Innovation and International Marketing Subject: Business Administration Emily A. Finlaw, Level and semester: Master's level, Spring 2011 Growth Through Innovation and International Marketing Growth Through Innovation and International Marketing Master Thesis, 2011 ENHANCING CURRENT FEEDBACK PROCESSES THROUGH SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING An exploratory study of Social Media and Social Media monitoring practices within an MNC looking to combine new practices with traditional customer- centric processes. Fredrik Bergstrand & Emily A. Finlaw “Today, everything is about Social Media” – Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein “Just as the eyes are the windows to the soul, business intelligence is a window to the dynamics of a business” – Cindi Howson “[Social Media monitoring] is not a car - but it is a vehicle for acquiring and sharing knowledge” – definition from Lexalytics, sited from Mike Marshall “Your most unhappy customers are your greatest source of learning.” – Bill Gates “Knowledge is not good if you don´t apply it” – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Acknowledgements It is our pleasure to thank all those who made contributions to this thesis over the past few months and throughout this learning journey. We would first like to thank Volvo Construction Equipment Region International for making this thesis possible. Thank you to Lars-Gunnar Larsson and Hanna Bragberg for creating a cutting-edge topic which has manifested into the inspiration for this thesis. -

Social Media Marketing in the Fashion Industry: a Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda

Social Media Marketing in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Science and Engineering 2020 Nishtha Kochhar 10081036 Department of Materials School of Natural Sciences Faculty of Science and Engineering 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 9 1.1 RESEARCH RATIONALE ............................................................................................................... 13 1.2 RESEARCH PURPOSE AND AIM .................................................................................................... 14 1.3 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................... 15 1.4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 15 CHAPTER 2 BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ........................................................................... 17 2.1 SOCIAL MEDIA AND FASHION ..................................................................................................... 17 2.2 CHAPTER SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 23 CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................... 24 3.1 -

Anxiety: an Epidemic Through the Lens of Social Media Holly M

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Anxiety: An Epidemic Through the Lens of Social Media Holly M. Wright Honors College, Pace Univeristy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Community Psychology Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Holly M., "Anxiety: An Epidemic Through the Lens of Social Media" (2018). Honors College Theses. 188. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/188 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anxiety: An Epidemic Through the Lens of Social Media by Holly M Wright BA Directing, International Performance Ensemble Mentored by Ion Cosmin Chivu An Undergraduate Thesis Presented to the Pforzheimer Honors College and Faculty of the School of Performing Arts Pace University New York City In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts, Directing, IPE with Honors Presented April 26th, 2018 Graduation: May 22nd, 2018 Wright 1 Abstract: Anxiety: An Epidemic was originally inspired by the mental health crisis in my hometown, Palo Alto, California, and evolved to specifically focus on social media-related anxiety. I examined the question: How has social media evolved over the last decade and what effect does the proliferation of social media have on the young adult population? I hypothesized that social media would have a predominately negative effect, especially on young women, and set out to create a theatrical piece inspired by my research. -

Instagram Porn Tags

Instagram porn tags Continue Period Time Key Development in Instagram 2010-2012 Instagram launches on the iPhone and grows to 13 employees and up to 30 million users (closing at $50 million under the $500 million estimate). It was acquired by Facebook in 2012. 2013-2016 Instagram introduces features such as videos, direct messages and advertising, and is growing to more than 400 million users. Instagram launched insta-stories in August 2016, with Live Stories later added in November 2016. Year month and date Event Type Details 2009 October 21 Product Kevin Systrom begins work on a project named Burbn. March 5, 2010 Systrom Funding closes the US$500,000 seed funding round with Baseline Ventures and Andreessen Horowitz while working on Burbn. 2010 May 19 Mike Krieger's team joins the Burbn 2010 project on October 6 The Instagram Product launches (from Systrom and Krieger) in the hope of making it easier to communicate through images. It nabs 100K users in one week. On December 12, 2010, Growth Instagram reached 1 million users. 2011 January Instagram product adds hashtags to help users discover both photos and each other. Instagram encourages users to make tags both specific and relevant, rather than tagging generic words like photos, highlighting photos and engaging like-minded people on Instagram. On February 2, 2011, Instagram's funding raised $7 million in Series A funding from a variety of investors, including Benchmark Capital, Jack Dorsey, Chris Sacca (via capital fund), and Adam D'Angelo. The deal values Instagram at about $25 million. Instagram's June 2011 growth affects 5 million monthly active users. -

Social Media and Digital Technology

Social Media and Digital Technology Part 1 - Social Media & Social Part 2 - How “Big Data” will Networking change your life • Learn the history of social • What is “Big Data” and who media and look at some of is collecting it? How will it the more familiar names be used for marketing? We such as Facebook and will look at advances in Twitter and how they are digital technology hardware used. We will discuss the and what might lie ahead. good, the bad and the ugly We will also explore how or social media and digital technology is used in consider some points to everyday life. ponder. Social Media and Digital Technology Part 3 - Social Media and Part 4 - Learning for life Journalism through MOOCs • From courtrooms to • MOOCs (“massively open communities to staffing, online classes” – Take a tour social media are changing of freely available online the way we get news – and courses and tutorials. challenging traditional Discuss implications of notions of what “news” is. accessibility as well as the cost and quality of higher education. We will explore some online education possibilities. Social Media and Digital Technology Part 5 - New media, privacy & Part 6 - Harnessing the the First Amendment wisdom of crowds online • New media make new law – • Crowds can be stupid and or at least, pose new brutal, but under the right questions for old law. How circumstances, crowd has the concept of “privacy” collaboration can lead to changed? How do we do stunningly good results. For jury selection? What kinds example, we will talk about of information do we trust – Wikipedia, discuss its flaws or do not trust? and give you a chance to actually make some changes to the entries. -

Standard Issue

Networking Knowledge_________ Volume 13 Issue 2 December 2020 Standard Issue Edited by Bissie Anderson Photo by Kyndall Ramirez on Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/@kyndallramirez Networking Knowledge 13 (2) Standard Issue (December 2020) Editorial Introduction BISSIE ANDERSON, University of Stirling This standard issue features six contributions from postgraduate and early career scholars working at the intersections of media, communications, education, sociology, and technoculture. In spite of the numerous challenges faced in 2020 due to the COVID-19 global pandemic and its knock-on effect on universities around the world, we are delighted to be closing the difficult year with the publication of this collection of articles. This is a reason for celebration – celebration of the authors whose work is featured herein, of cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary connections that allow us to engage in academic dialogue across borders, of our resilience as a global collective of researchers, and our ongoing commitment to knowledge exchange. The articles in this standard issue differ in their objects of inquiry – from sound in digital games, social networking sites, and digital technology in education, to broadcast journalism and romantic comedies, but they broadly converge around a common focus on temporality and time. Between them, the articles present a good mix of empirical work and significant conceptual development, moving forward theoretical debates in the fields of media and communications. Concepts are either developed, through in-depth engagement with the extant literature (Amaral 2020; Martins and Piaia 2020), or tested through empirical studies using a variety of methods – from surveys (De Andrade and Calixto 2020) to digital ethnography (Polivanov and Santos 2020) to participant observation and interviews (Gomes, Vizeu, and De Oliveira 2020). -

The Role of Social Media in Intercultural Adaptation: a Review of the Literature

English Language Teaching; Vol. 11, No. 12; 2018 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Role of Social Media in Intercultural Adaptation: A Review of the Literature Basim Alamri1 1 English Language Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Basim Alamri, English Language Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Received: September 17, 2018 Accepted: November 10, 2018 Online Published: November 14, 2018 doi: 10.5539/elt.v11n12p77 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n12p77 Abstract As international students, sojourners, and immigrants arrive at host cultures, they usually employ certain means and strategies to adjust to the traditions and norms in these cultures. The present article provides a review of the literature about the impact that social networking sites (SNSs), as one of these strategies, have on the process of intercultural adaptation. The article also points out the definitions and several types of SNSs and a number of common models of intercultural adaptation. The literature shows that SNSs have been used for several purposes during the intercultural adaptation process such as: (1) to remain in contact with their family members and friends in their home countries, (2) to obtain social capital, and (3) to socially adjust in educational settings. The pedagogical implications derived from the literature are manifested in threefold: connections and relationships, community, and acculturation. Keywords: intercultural adaptation, adjustment, social networking sites (SNSs), social media 1. Introduction Newcomers to foreign cultures have implemented various technologies to help them in the cultural adaptation and acculturation process. In recent years, the most common and useful techniques utilized by the newcomers is social media, which plays a pivotal role in connecting people around the globe together in order to share and exchange knowledge and cultural traditions. -

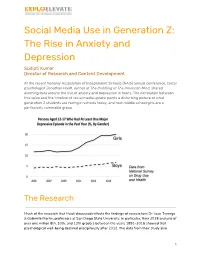

Social Media Use in Generation Z: the Rise in Anxiety and Depression Sudipti Kumar Director of Research and Content Development

Social Media Use in Generation Z: The Rise in Anxiety and Depression Sudipti Kumar Director of Research and Content Development At the recent National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) annual conference, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of The American Mind, shared alarming data around the rise of anxiety and depression in teens. The correlation between this spike and the timeline of social media uptake paints a disturbing picture of what generation Z students are facing in schools today, and how middle school girls are a particularly vulnerable group. The Research Much of the research that Haidt discussed reflects the findings of researchers Dr. Jean Twenge & Gabrielle Martin, professors at San Diego State University. In particular, their 2018 analysis of over one million 8th, 10th, and 12th graders between the years 1991–2016 showed that psychological well-being declined precipitously after 2012. Th e data from their study also 1 found that teens who spent more time on electronic communication and less time on non-screen activities had lower overall psychological well-being.1 Mean happiness, 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, Monitoring the Future Source: Jean Twenge Another paper just released in February 2020 by the same authors in the Journal of Adolescence studied more than 200,000 young people from the US and the UK. In this data set, they compared heavy users of digital media (five or more hours a day) versus light users (one hour or less a day). Heavy data users were 48-171% more likely to be unhappy or have suicide risk factors such as depression or suicidal ideation.2 The study also found, as Haidt mentioned in his talk, that girls were more likely to spend their online time on social media sites and boys were most likely to spend it on gaming devices, thus compounding the issue for young girls versus boys.