Hispanic Influences in the Northern Rockies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ravalli County 4-H Horse Project Guidelines

4-H PLEDGE I Pledge my HEAD to clearer thinking, My HEART to greater loyalty, My HANDS to larger service, And my HEALTH to better living, RAVALLI COUNTY 4-H For my club, my community, my country and my world. HORSE PROJECT GUIDELINES 2017-2018 The guidelines may be amended by the Ravalli County 4-H Horse Committee each year between October 1st and January 30th. No changes will be made from February 1st through September 30th. If any member or leader wants to request an exception to any rule in the guidelines, they must request a hearing with the Ravalli County 4-H Horse Committee. Updated December 2017 Table of Contents RAVALLI COUNTY 4-H HORSE COMMITTEE CONSTITUTION ............................................................................................................................. 3 ARTICLE I - Name ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 ARTICLE II - Purpose ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 ARTICLE III - Membership ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ARTICLE IV - Meetings .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

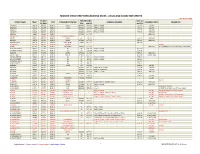

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

The Morgan's Role out West

THE MORGAN’S ROLE OUT WEST CELEBRATED AT VAQUERO HERITAGE DAYS 2012 By Brenda L. Tippin Stories of cowboys and the old west have always captivated Americans with their romance. The California vaquero was, in fact, America’s first cowboy and the Morgan horse was the first American breed regularly used by many of these early vaqueros. Renewed interest in the vaquero style of horsemanship in recent years has opened up huge new markets for breeders, trainers, and artisans, and the Morgan horse is stepping up to take his rightful place as an important part of California Vaquero Heritage. THE MORGAN CONNECTION and is becoming more widely recognized as what is known as the The Justin Morgan horse shared similar origins with the horses of “baroque” style horse, along with such breeds as the Andalusian, the Spanish conquistadors, who were the forefathers of the vaquero Lippizan, and Kiger Mustangs, which are all favored as being most traditions. The Conquistador horses, brought in by the Moors, like the horse of the Conquistadors. These breeds have the powerful, carried the blood of the ancient Barb, Arab, and Oriental horses— deep rounded body type; graceful arched necks set upright, coming the same predominant lines which may be found in the pedigree out of the top of the shoulder; and heavy manes and tails similar of Justin Morgan in Volume I of the Morgan Register. In recent to the European paintings of the Baroque period, which resemble years, the old style foundation Morgan has gained in popularity today’s original type Morgans to a remarkable degree. -

GRUNDY COUNTY 2019 All American Fair

GRUNDY COUNTY 2019 All American Fair Sponsored by the Grundy County Agricultural Society Recipient Grundy County Fair website: www.grundycountyfair.com Grundy County Fair 4-H & FFA Entries: http://grundy.fairentry.com Grundy County Fair Open Class Entries: http://grundyopen.fairentry.com Association of Fairs 2014 Blue Ribbon Fair Award Grundy County Fairgrounds Grundy Center, Iowa The Fairgrounds are on the south edge of town. Enter the Fairgrounds on 4th Street or 1st Street. 21→ 1 15 16 3 2 5 19 18 14 20 4 6 13 5 7 8 12 9 11 10 Parking is allowed on the grass area along the fence line, to the North of the main fairground road and on the south side of the fairgrounds Buildings 11. Wheelock Building 1. Building #1 12. Beef Barn 2. Shelter 13. Bucket Calf Barn 3. Upper Bathrooms 14. Alumni Building 4. Swine Barn 15. Exhibit Building & Bathrooms 5. Sheep Barn 16. Shelter 6. Upper Show Arena & 4-H Office 17. Open Class 7. Dairy Barn 18. Gazebo 8. Poultry Barn 19. Grandstands 9. Rabbit Barn 20. Band & Beer Garden 10. Horse Arena 21. New Campgrounds TABLE OF CONTENTS: FAIR SCHEDULE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…. 4 FAIR OFFICIALS………………………………………………………………………..……………………………………………..………. 7 GENERAL INFORMATION Alcohol Policy …………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………… 9 Lost & Found ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 9 Complaint Procedure………………………………………………………………………………………….………………. 9 Grundy County 4H & FFA Show Premiums………………………………………………………………………….. 9 Camping & Overnight Information…………………………………………………………………………..……….. -

Stories of Words: Spanish

Stories of Words: Spanish By: Elfrieda H. Hiebert & Wendy Svec Stories of Words: Spanish, Second Edition © 2018 TextProject, Inc. Some rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-937889-23-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. “TextProject” and the TextProject logo are trademarks of TextProject, Inc. Cover photo ©2016 istockphoto.com/valentinrussanov. All rights reserved. Used under license. 2 Contents Learning About Words ...............................4 Chapter 1: Everyday Sayings .....................5 Chapter 2: ¡Buen Apetito! ...........................8 Chapter 3: Cockroaches to Cowboys ......12 Chapter 4: ¡Vámonos! ...............................15 Chapter 5: It’s Raining Gatos & Perros!....18 Our Changing Language ..........................21 Glossary ...................................................22 Think About It ...........................................23 3 Learning About Words Hola! Welcome to America, where you can see and hear the Spanish language all around you. Look at street signs or on menus. You will probably see Spanish words or names. Listen to the radio or television. It is likely you will hear Spanish being spoken. Since Spanish-speaking people first arrived in North America in the 16th century, the Spanish language has been part of American culture. Some people are being raised in Spanish-speaking homes and communities. Other people are taking classes to learn to speak and read Spanish. As a result, Spanish has become the second most spoken language in the United States. Every day, millions of Americans are speaking Spanish. -

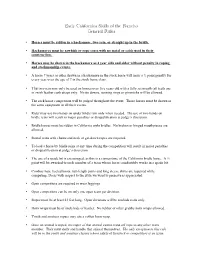

Early Californios Skills of the Rancho General Rules

Early Californios Skills of the Rancho General Rules • Horses must be ridden in a hackamore, two-rein, or straight up in the bridle. • Hackamores must be rawhide or rope cores with no metal or cable used in their construction. • Horses may be shown in the hackamore as 4 year olds and older without penalty in roping and stockmanship events. • A horse 7 years or older shown in a hackamore in the stock horse will incur a ½ point penalty for every year over the age of 7 in the stock horse class. • The two-rein may only be used on horses over five years old with a fully set mouth (all teeth are in) with leather curb straps only. No tie downs, running rings or gimmicks will be allowed. • The sock horse competition will be judged throughout the event. Those horses must be shown in the same equipment in all their events. • Rider may use two hands on under bridle rein only when needed. The use of two hands on bridle reins will result in major penalties or disqualification at judge’s discretion. • Bridle horses must be ridden in Californio style bridles. No broken or hinged mouthpieces are allowed. • Romal reins with chains and neck or get-down ropes are required. • To lead a horse by bridle reins at any time during the competition will result in major penalties or disqualification at judge’s discretion. • The use of a spade bit is encouraged, as this is a cornerstone of the Californio bridle horse. A ½ point will be awarded to each member of a team whose horse comfortably works in a spade bit. -

CALAFIA Home Page

Spanish and Mexican California Collections at Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley Alviso Family Papers: Documentos para la historia de California BANC SS C-B 66 Archivo del Obispado de Monterey y Los Angeles BANC MSS C-C 6 Archivos de las Misiones BANC MSS C-C 4, BANC MSS C-C 5 Argüello (José D.) Documents BANC MSS C-A 308 Bancroft Reference Notes BANC MSS 97/31 c Bancroft Reference Notes for California BANC MSS B-C 12 Bowman, J.N., Papers Regarding California History, undated BANC MSS C-R 18 Castro (Manuel de Jesús) Papers BANC MSS C-B 483 Colegio de San Fernando: concerning missions in Alta and Baja California BANC MSS M-M 1847 Documentos de la Comisión Confidencial [Vega, Plácido] BANC MSS M-M 325-339 Documentos para la historia de California BANC MSS C-B 98 Documentos para la historia de California, 1749-1850 [Carillo, Domingo A.I.] BANC MSS C-B 72 Documentos para la historia de California, 1799-1845 [Carillo, José] BANC MSS C-B 73 Documentos para la historia de California, 1801-1851 [Carillo, Pedro C.] BANC MSS C-B 74 Documentos para la Historia de California, 1802-1847 [Olvera, Agustín] BANC MSS C-B 87 Documentos para la historia de California, 1821-1872 [Coronel, Antonio F.] BANC MSS C-B 75 Documentos para la historia de California, 1827-1858 [Fitch, Henry D.] BANC MSS C-B 55 Documentos para la historia de California, 1827-1873 [Avila, Miguel] BANC MSS C-B 67 Documentos para la historia de California, 1828-1875 [Castro, Manuel de Jesús] BANC MSS C-B 51- 52 Documentos para la historia de California, 1846-1847, and especially concerning the Battle of San Pascual: 1846-1876 BANC MSS C-B 79 Documentos para la historia de California, 1878 [Del Valle, Ignacio] BANC MSS C-B 99 Documentos para la historia de California [Bonilla, José M.] BANC MSS C-B 71 Documentos para la historia de California: colección del Sr. -

Rulebook21.Pdf

APPALOOSA A HORSE FOR ALL REASONS 2 0 2 Share your reasons with us at [email protected] 1 RIDE WITH US into the NEW DECADE ApHC DIRECTORY The Appaloosa Horse Club is on Pacific Time, three hours behind New York, two hours behind Texas, one hour behind Colorado, in the same time zone as California. Business hours are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday. Administration Member Services Executive Secretary— Membership information ext. 500 Lynette Thompson ext. 249 [email protected] [email protected] Administrative Assistant— Museum [email protected] www. appaloosamuseum.org [email protected] Director— Crystal White ext. 279 Accounting [email protected] Treasurer— Keith Ranisate ext. 234 Racing Coordinator— Keri Minden-LeForce ext. 248 Appaloosa Journal [email protected] [email protected] Editor— Registration Dana Russell ext. 237 General information ext. 300 [email protected] Registry Services— Advertising Director— [email protected] Hannah Cassara ext. 256 [email protected] Performance General Information ext. 400 Art/Production Director— Barbara Lawrie Performance Department Supervisor— [email protected] Keri Minden-LeForce ext. 248 [email protected] Graphic Designer & Circulation Manager— Judge Coordinator and Show Secretary— Jonathan Gradin ext. 258 Debra Schnitzmeier ext. 244 (circulation & subscriptions, address [email protected] changes, missing & damaged issues, Appaloosa Journal Online) [email protected] [email protected] Show Results/Show Approvals— [email protected] Deb Swenson ext. 265 [email protected] Information Technnology ACAAP— Information Technology Supervisor— Amber Alsterlund ext. 264 Dave O’ Keefe ext. 251 [email protected] [email protected] Trail & Distance Coordinator— [email protected] ext. 221 Marketing Marketing/Public Relations Director— Youth Programs Hannah Cassara ext. -

Read Book Through England on a Side-Saddle Ebook, Epub

THROUGH ENGLAND ON A SIDE-SADDLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Celia Fiennes | 96 pages | 02 Apr 2009 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141191072 | English | London, United Kingdom Sidesaddle - Wikipedia Ninth century depictions show a small footrest, or planchette added to the pillion. In Europe , the sidesaddle developed in part because of cultural norms which considered it unbecoming for a woman to straddle a horse while riding. This was initially conceived as a way to protect the hymen of aristocratic girls, and thus the appearance of their being virgins. However, women did ride horses and needed to be able to control their own horses, so there was a need for a saddle designed to allow control of the horse and modesty for the rider. The earliest functional "sidesaddle" was credited to Anne of Bohemia — The design made it difficult for a woman to both stay on and use the reins to control the horse, so the animal was usually led by another rider, sitting astride. The insecure design of the early sidesaddle also contributed to the popularity of the Palfrey , a smaller horse with smooth ambling gaits, as a suitable mount for women. A more practical design, developed in the 16th century, has been attributed to Catherine de' Medici. In her design, the rider sat facing forward, hooking her right leg around the pommel of the saddle with a horn added to the near side of the saddle to secure the rider's right knee. The footrest was replaced with a "slipper stirrup ", a leather-covered stirrup iron into which the rider's left foot was placed. -

JOE BARKSHIRE ESTATE AUCTION Sante Fe Morris Morris 16.5” 15.5” 15.5” 13” 13” 12” Saturday, October 29Th, 2016 9:00 A.M

James Morris Longhorn omas JOE BARKSHIRE ESTATE AUCTION Sante Fe Morris Morris 16.5” 15.5” 15.5” 13” 13” 12” Saturday, October 29th, 2016 9:00 A.M. • Family Living Center • Mt Expo Park 400 3rd Street North • Great Falls, MT Simco Longhorn Buck Steiner Blue River Morris Morris 15” 15.5” 14.5” 15.5” 15” 12” Kelly Longhorn, 79” Crockett Renalde Brass Sleigh Bells Longhorn, 42” Buermann Spanish Style Mexican Buermann Kelly Don Ricardo Horsehair Lap Robe Ft. Shaw Mailboxes Rawhide Reins Rawhide Romal Sliester US Calvary W. T. Gilmer Silver Mtd. Spur Straps Ario Invoice Morris Saddlery, 12”, junior barrel saddle, stamped & carved, Rancho Grande Magdalena & Son, 13.5”, watusi swells, ta- Rawhide reins with romal, Santa Inez type, excellent! SADDLES rawhide horn, padded green seat, rhinestone silver con- pederos COWBOY COLLECTIBLES Rawhide roping reins with romal, four strand braid chos, brand new Rex Newell, Coleman, TX, 13”, bear trap Mexican silver /copper inlaid curb bit in braided leather Morris Saddlery, Caballo, NM, 15”, association, at plate dou- Morris Saddlery, 16”, roping saddle, 15.5”, double rig S.D. Myres, El Paso, 14”, stock saddle, double rig Vintage U.S. postal mail boxes, from Ft. Shaw, MT Post Oce, headstall and silver mtd bit ble rig, rough out, rawhide bound cantle & horn, brand new Morris Saddlery, 16”, Roping saddle, 15.5”, double rig Sante Fe, 13.5” barrel saddle, rawhide horn 3 sections, 33”w, 25”w & 7”w, all 47”h x 11”d, all metal Buermann silver mtd spade bit w/ braided leather headstall & reins Morris Saddlery, 13”, -

March, 1947 No

The State Historical Societt of Colorado Libra~ THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published bi-monthly by The State Historical Society of Colorado Vol. XXIV Denver, Colorado, March, 1947 No. 2 Quarrying the Granite for the State Capitol \V ALLACE l\fooRE AND Lors BoRLAKo ·::, B,rom the face of a granite cliff at Aberdeen. six miles from <l unnison, Colorado, on South Beaver Creek, the gleaming {!t·a:· stoll e which forms the walls of the state capitol in De11Yer \ms r1 uarriecl. The ledges have the appearance of being barely chipped and are said to contain sufficient granite" to build New York Cit:·." A plan to use sandstone for the capitol had been cliseussecl. hut \nlS put aside, and on April l , 1889, GoYernor .Joh ~\. Coope1· appointed a capitol commission to select material: Charles -1 . Hughes, Denver ; Otto Mears, Silverton; ex-GoYernm· .J ohu h Routt, Denver; Benjamin F. ('1·owell, Colorado 8pring1'. \\·ith 11 onald \V. Campbell as secretary. Forthwith, the owners of qmn-- 1·ies throughout the state were notified through their local papers to send samples if they so desired, and to make estimate of cost. Investigation of the South BeaYer granite had been made b:· I•, . G. Zugelder of Gunnison in March, 1888, and the first sample 1rns carried ou1 on snowshoes and sent to Denver for a test. Loca ti on was made April 16, 1889, by F. G. Zugelcler. h F. Zngelder. W. H. Walter, and T. TJ. Walter. [n 1880. as rarl:' as February 8. William Geddes of the firm of <le clcles & Seerie. -

The Kumeyaay: Native San Diegans N 1542, Spanish Conquistador Juan

Queen Califia Voyage to California J?8==<I>IL99#9<KF8CM8I<QD@:?<CC<>@C:?I@JK U-T n 1542, Spanish conquistador The original DETAIL ABOVE Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sailed up ‘California Dream’ The word “California” existed the uncharted coast of present-day in fiction before it was ever on California in search of treasure a map. A novel published DETAIL BELOW around 1500 had “an island aInd passage to the Atlantic. The journey called California, very near to A mural at the yielded neither and Cabrillo died along the region of the Terrestrial Mark Hopkins Hotel Paradise.” In the story, the in San Francisco the way. It was 50 years after Christopher island was populated by “black depicts Queen Amazons” who rode gri"ns Calafia and her Columbus landed in North America and and used gold armor and Amazons greeting was Spain’s final push to find wealth on weapons; they were ruled by visitors in the beautiful queen Calafia. California. the scale of the Aztecs and Incas. The story is in line with other Amazon myths: California is a wealthy, hard-to-reach paradise filled with free, warrior women. Cabrillo — and other mariners for the next two centuries — missed San Francisco Bay. Fog and high cli!s obscure the harbor’s entrance. 7 The fleet IMAGES COURTESY turns south INTERCONTINENTAL a second 4 Two Channel Brief stop preludes wide settlement MARK HOPKINS time to Islands were named Though Cabrillo’s visit was relatively non-violent, it preceded later return home. after the two larger settlement that would kill or displace most of the native Californians.