Romance of Aerophilately, Pt. 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Late Material Agenda Supplement for Licensing Sub-Committee, 28/06

LICENSING SUB-COMMITTEE 28 JUNE 2016 LATE MATERIAL Double Tree by Hilton, 1 Skerne Road, Kingston upon Thames KT2 5FL - Appendix A The following material has been received since the publication of the agenda for this meeting: Submission from applicant Positioning Document from applicant Dispersal Policy from applicant Conditions agreed with RBK Trading Standards IN THE MATTER OF: A PROPOSED HOTEL DOUBLE TREE BY HILTON AT 1 SKERNE ROAD, KINGSTON UPON THAMES HEARING: 28TH JUNE 2016 SUBMISSION ON BEHALF OF REQ OPCO (KINGSTON) LTD APPLICANT WRITTEN SUBMISSION ON BEHALF OF THE APPLICANT 1. This is an application for the grant of a Premises Licence pursuant to Section 17 of the Licensing Act 2003 for a new Hotel to be known as Double Tree by Hilton and it is proposed to have 146 guest bedrooms. Planning Permission was granted in 2008 for the Hotel including “conference banqueting and meeting rooms” as part of a major redevelopment of the area. 2. The proposed site is to operate as a full service Hotel managed by Interstate Hotels and Resorts Europe (the largest hotel management globally managing over 500 hotels and resorts). It is proposed that the Hotel will form part of the world wide Hilton organisation. Hilton is one of the largest Hotel operators in the world. There are currently 450 Double Tree by Hilton Hotels. There are approximately 30 Hotels across England, Wales and Scotland. At the present time, the closest Doubletree by Hiltons geographically to Kingston upon Thames are in Chelsea and Heathrow Airport. The development therefore proposes the introduction of this major and internationally known Hotel brand to Kingston upon Thames. -

A.H.S.A. Newsletter

A.H.S.A. NEWSLETTER Published by the Aviation Historical Society of Australia Inc. A0033653P, ARBN 092-671-773 Volume 27 Number 1, March 2011 Print Post approved 318780/00033 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ahsa.org.au Editor: NEIL FOLLETT EDITORIAL. We ask all our members who take advantage of the In this issue of the newsletter we have devoted three direct deposit method of payment to ensure that they pages to the unveiling of a plaque to Gertrude McKen¬ include their name with any direct debits made. We zie. This was an AHSA initiative and was cost neutral, have had a couple of occasions where those details due to generous donations from The City of Kingston, were not given which made it difficult to determine who the Victorian Division of the Australian Womens Pilot s had paid. Association, the McKenzie family, AHSA members and past students of the McKenzie Flying School. Commemoratin Pioneer Aviators. From our Darwin correspondent: Mike Flanagan This is the type of project the AHSA should be involved in to further its aims of recording and preserving Austral¬ In November 2006 three new thoroughfares were gazet¬ ia s rich aviation history. ted in the Northern Territory. In all our capital cities there were early airfields where All were in the Darwin Airport area and all three com¬ our pioneer pilots operated from. How many of these are memorated the names of pioneer aviators’. marked? Probably none. They are: Collopy Road, Neale Street and Osgood Drive. Melbourne for example had five: South Melbourne, Port Being honoured are: Melbourne, Glenroy, Glenhuntly and Coode Island. -

Sopwith Aviation Company – the First World War Comes to an End

SOPWITH AVIATION COMPANY – THE FIRST WORLD WAR COMES TO AN END The 1918 Sopwith Snipe was the successor to the Camel with a more powerful Bentley rotary engine. It was the RAF’s front line fighter until 1926 The Sopwith Camel had its shortcomings, including poor upward view for the pilot. In 1917 Herbert Smith designed its successor with the pilot's eye-line level with the top wing giving uninterrupted forward and upward views. Sopwith leased a large new National Aircraft Factory in North Kingston to build huge numbers of Snipe. The Snipe was very successful in France for the last few months of the war. Over 2,000 Snipe were built and after the war they served in the Home Defence role and overseas, remaining in RAF service until 1926. The 1918 Sopwith Salamander TF 2 was an armoured ground attack fighter developed from the Snipe Hundreds of these aircraft were being built alongside the Snipe in Kingston when the war ended earlier than predicted and all un-started orders were cancelled. A few Salamanders did reach France before the armistice. The 1918 high performance Sopwith Dragon was a Snipe with the promising ABC Dragonfly radial engine which proved to be very unreliable The Sopwith T1 Cuckoo torpedo bomber, just too late for the war, was retained post-war as the only RAF torpedo aeroplane which could operate from aircraft carriers Sopwith developed the Cuckoo from their B1 Bomber to meet an Admiralty requirement to attack the German fleet in its home anchorages. All but the prototype were built by sub-contractors, Sopwith being too busy satisfying the huge demand for its fighters. -

Pdf 363.29 KB

August News Letter 2013 I do apologies for our news letter in the normal format being two issues behind. Museum Australia Victoria Awards As announced at the last meeting we received a message from Museum Australia Victoria, “I am delighted to be able to announce that the Box Cottage Museum has been short-listed for one of the new cataloguing prizes to be announced at this year’s Victorian Museum Awards. There will be two prizes announced for VC cataloguers – one for the highest amount of items catalogued by organisations with paid staff, and the other for the highest amount of items catalogued by organisations with volunteer staff.” This meant that the Society was top 5 out of 150 finish in the MAV Awards for small Museums, when ask by the compare of the event for volunteers to hold up their hands, the weren’t many hand up. We did feel lonely, However we had an interesting night and the Winner was in the “Volunteer Run Organisations Category”: is Greensborough & District Historical Society. Congratulations Joan and Carol for the nomination and for all their hard work. Mentone Park Primary by Joan Moore Bill and I went to Mentone Park Primary School Grade 3 & 4 , Monday 12th, to talk about Life in Moorabbin's early years. Students were interested to see pictures of the olden days and try out the butter turn and the stereo scope viewer. August Open Day. Please all members remember our Open Day the 25th of August . With Dignitaries and a few visits expected we will help on the day. -

1 Harry George Hawker

Harry George Hawker (1889–1921) Harry George Hawker was a photographic pilot for Aerofilms Ltd who flew sorties for the company during the years 1919 to 1920. “Harry – the cheery little Australian who grinned a lot and flew like the devil” (Terry Gwynn-Jones, 1984:119). Harry was born on the 22 nd January 1889 in Melbourne Australia. His parents were George and Mary Ann Hawker. Harry attended school in Australia until the age of 12 at which point he became a trainee mechanic at the Hall & Warden bicycle depot in Melbourne in 1901. After four years of training at Hall & Warden he joined the Tarrant Motor and Engineering Co in 1905 as a qualified mechanic. During the following years Harry proved himself as a skilled mechanic and an entrepreneur, setting up his own car servicing workshop in 1907 (Sheehy, 1983). In 1911 Harry moved to England and, only a year after arriving, secured a job with the Sopwith Aviation Company as a mechanic (Gwynn-Jones, 1984:119). Soon after starting his job Harry began flying lessons under the tuition of Thomas Sopwith, the founder of the company and Harry’s new employer. It didn’t take long before Harry’s potential as a top class pilot was recognised especially when he flew solo after only four training lessons. Harry received his Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificate (no. 297) on the 17 th September 1912 (Great Britain, Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificates, 1910-1950). After gaining his certificate Harry tutored new recruits at the Sopwith School including Major H. M. -

PRESS RELEASE Catalina 100 Year Round

Monday 12 August 2013 IWM Duxford-based Catalina takes on a round-Britain challenge Commemorating a 100 year old flight in the aircraft’s own 70th birthday month On Wednesday 21 August, Catalina G-PBYA, operated by Plane Sailing Air Displays Limited and based at IWM Duxford, undertakes a remarkable aviation challenge. Honouring the daring flying expeditions of the pioneer aviators, the Catalina will undertake, in its centenary year, the 1913 Circuit of Britain flight, which was flown by pilot Harry Hawker and mechanic Harry Kauper, both Australians, in a Sopwith Waterplane. The Catalina celebrates its 70th birthday this month, making it the oldest UK-based airworthy amphibian. In 1913, the Circuit of Britain Race was the first major British competition for seaplanes. It was supported by Lord Northcliffe, the proprietor of the Daily Mail, who was a great fan of aviation races. Shell Aviation provided the lubricants for the original race and will be doing the same 100 years on. The route in 1913, as reported by Flight magazine, started and finished at Southampton Water, with eight control points en route. These were the Royal Temple Yacht Club in Ramsgate, the Naval Air Station in Yarmouth, the Grand Hotel in Scarborough, the Palace Hotel in Aberdeen, the Naval Air Station in Cromarty, the Great Western Hotel in Oban, the Royal St George Yacht Club in Kingstown, Dublin and the Royal Cornwall Yacht Club in Falmouth. While the airspace in 2013 is somewhat more restricted then 100 years ago, the crew of the Catalina intends to follow the 1913 route as closely as possible. -

Robbins & Porter Monoplane—Statement of Significance

The Robbins & Porter Monoplane of 1913 Statement of significance The Robbins & Porter Monoplane of 1913 Statement of significance Dirk HR Spennemann The aircraft built in the first half of 1913 by the Albury mechanics Azor Robbins and Alexander Porter is of high cultural significance as it was the first Australian-designed and Australian-built monoplane, fitted with the first Australian-built air-cooled aircraft engine, that actually became airborne and flew. The decade before the outbreak of World War I saw modern transportation systems, such as the motorcar and aircraft, being introduced to Australia, with flying in particular attracting the attention of the press of the day.[1] The motorcar business was thriving in metropolitan as well as country Victoria,[2] and fast cars and flying became the aspirations of many young and technically minded men. Among these were Azor Robbins[3] and Alexander Porter,[4] two Melbourne mechanics,[5] who in July 1911 decided to set up on their own, establishing a motor garage in Albury, NSW.[6] Of the two, Robbins was the businessman with a sharp engineering mind,[[8] while Porter was a motor enthusiast-cum-mechanic.[9] During the late nineteenth century people across the globe engaged in experiments to develop heavier-than-air flying machines. In Australia, trials by Lawrence Hargrave from 1885 onwards proved by 1893 that double box kites gave enough lift to provide a stable aerial platform. The first powered flight with a petrol engine was achieved in 1903 when the Wright brothers flew their design at Kitty Hawk.[25] Truly controlled powered flight occurred with Santos Dumont in 1906. -

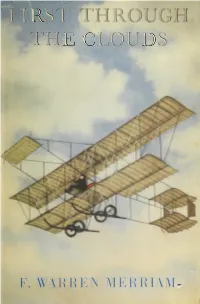

FIRST THROUGH the CLOUDS Frontispiece

**— k> V LOU F. WARREN MERRIAM PRICE 21$. NET S well as being the first man to fly his box-kite through the clouds Aof a misty summer morning and out into the sunshine above, Commander Warren Merriam was also well-known as one of the most successful of the early flying instructors. He it was who taught to fly many of the pilots of the first world war men who, twenty-five years later, had become senior officers of the R.A.F. One of them, Air Chief Marshal Sir Philipjoubert, bears flatter ing witness to Commander Merriam's qualities in the Foreword to this book. A. V. Roe, J. T. C.Moore-Brabazon, the Short Brothers, Geoffrey de Havilland, Colonel Cody, Claude Graham-White and T. O. M. Sopwith are others of the pioneers whom Commander Merriam knew in their early days and of whom he fascinatingly writes. Aviation was then still in a highly experimental stage and the revolutionary methods and early crashes of those days were the price which had to be paid for aerial supremacy in both world wars. Apart from its intrinsic interest, the story which Commander Merriam has to tell is of no little importance in the history of British aviation. Its fascina tion, and its vividness, is greatly in creased by the remarkable collection of fifty photographic illustrations of the early days of flying. A BATSFORD BOOK The jacket design is by MAURICE WILSON fttom % pitting ItBttattg of Ulallu Jialii. FIRST THROUGH THE CLOUDS Frontispiece The Author as a Flight-Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Air Service, Chingford, 1915 The Autobiography of a Box-Kite Pioneer By F. -

1T(U() ?I~ ... :• Titne to Sell???

May, 195Q 'Vol (JO, No. 8 I 9 5 9 s u p p L E M E N T • • • 1t(U() ?I~ ... :• Titne To Sell??? THEN CONSIDER AUCTION AS YOlJR METHOD IRWIN HEIMAN The benefit of more than 30 years experience 1n stamp dealing is yours - our clientele is world wide and actively in- terested in every field of collecting. ·Specialist-prepared auction catalogues will present your holdings in a manner to a s ~ure you t_he maximmn net result. An immediate, interest free, cash advnnce c:m be made on suitable properties. Our commission is 20 % of the gross realization; there is no other charge. Full settlement· is made within 30 days after sale. Early. Fall dates are availahle now. PRIVATE SALE: Some properties, because of their nature, are best sold privately. Our constant awareness of the Philatelic Market often enables u s to effect a sale within a few days of receipt. W c place many valuable properties each year in this manner. Serving American Philately Since 1926 IRR71N HEIMAN~ Inc. 2 WEST 46th STREET ~ NEW YORK 36, N.Y. THE AMERICAN AIR MAIL SOCIETY -.~IBPOST A Non•Profit Corporati.on Incorporated 1944 rJ.LD_-;f'OllBNAL Organized 1923 Under the Laws of Ohio Official Publ1cation of the PRESIDENT John J. Smith AMERICAN Am MAIL SOCIETY Ferndale & Emerson sts. Philadelphia 11, Pa. Volume 30 No. 8 Issue No. 349 SECRETARY-TREASURER Ruth T. Smith CONTENTS For May, 1959 Ferndale & Emerson Sta. Philadelphia 11, Pa. Articles VICE-PRESIDENTS Volume III of American Air Mail Bernard Davis Ca:talogue Now Available .............. -

Glenn Curtiss Born at Hammondsport NY, May 21, 1878

Glenn Curtiss Born at Hammondsport NY, May 21, 1878. Died 1930. The love of high speeds and mechanical devices led the gifted Glenn H. Curtiss of Hammondsport, New York, to become the first U.S. competitor in international air meets and a pioneer in the development of aircraft in the early 1900s. Curtiss began his high-speed career by racing and building bicycles. His next step was to buy and improve one-cylinder bicycle engines. Then, as motorcycles started being developed, he began building and racing them. By 1902, Curtiss was manufacturing customized motorcycles under the trade name Hercules. Curtiss entered his first motorcycle race in 1902 and although he did not win, his mechanical talents were recognized, and many motorcycle enthusiasts ordered his rugged, well performing machine. In 1903, Curtiss entered two races in two different cities on Memorial Day and won both. The two- cylinder engine that he used to power his cycles soon began to draw attention from motorcyclists and from early aircraft builders as well. Curtiss continued improving his engines and competing in races. In 1907 at Ormond Beach, Florida, he reached the record speed of 136 miles per hour (219 kilometres per hour) on his motorcycle powered by a 40-horsepower (30-kilowatt), V-8 engine. He began to be called "the fastest man alive." Thomas Baldwin, a balloonist, saw Curtiss race and recognized how good his engine was. He realized that the engine could work on an aircraft as well as on a motorcycle. He ordered one for his balloon from Curtiss, who delivered a modified motorcycle engine. -

Sopwith Aviation – the Founding Fathers

SOPWITH AVIATION – THE FOUNDING FATHERS Thomas Octave Murdoch Sopwith – Pioneer aviator, engineer, industrialist and businessman; founder of Sopwith Aviation, Hawker Aircraft, Hawker Siddeley Aviation and the Hawker Siddeley Group Thomas Octave Murdoch Sopwith was born in 1888 the son of a wealthy industrialist. Enthused by a passenger flight in 1910 he bought a Howard Wright monoplane and started teaching himself to fly at Brooklands. After a crash he bought a Howard Wright pusher biplane and on November 21st, 1910, with just nine flying hours, Sopwith gained Royal Aero Club Aviator’s Certificate No.31. In 1911 Sopwith entered many competitions in England, on the Continent and in the USA and was very successful. With his prize money he started the Sopwith School of Flying at Brooklands in February 1912. Fred Sigrist - TOM Sopwith’s engineer and works manager Fred Sigrist, Sopwith’s engineer from his luxury motor yacht ‘Neva’ and who accompanied Sopwith during his competition flying, was in charge of maintenance, overhaul and modification of the school aircraft. He later became Works Manager and had a genius for organising quantity production. During World War I he was responsible for the manufacture of thousands of Sopwith aircraft. The first Sopwith built aircraft was Sigrist’s 1912 ‘Hybrid’ Fred Sigrist built a two-seat tractor biplane for instructional use at the Sopwith School of Flying. With wings from their Wright biplane on his newly designed fuselage, it was known as the Hybrid. It was purchased for the Royal Navy which instantly made Sopwith approved military aircraft contractors. The money was used to purchase a Roller Skating Rink in Kingston upon Thames as the factory. -

TOUCHDOWN the OBAN AIRPORT Newsletter

TOUCHDOWN The OBAN AIRPORT Newsletter Issue 5 May-Jul 2013 Latest From OBAN AIRPORT FEATURES Latest From Oban Airport Following on from the last issue we have a bumper newsletter for you this time. Some of the comments I have received about issue 4 have INSIDE THIS ISSUE been very good indeed and in particular, the article about Coll’s five Historic Airport Visitor airports. I have also been quite busy with a Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) audit, three annual exercises (Colonsay, Coll and Oban) and not to Glenforsa Isle Of Mull mention another appearance on TV’s Reporting Scotland. The Oban Times have also reported on the scheduled service and were given Annual Emergency information regarding statistics obtained from the airline and the airport. Exercises Island Crews Fire Training As stated above, with the help of one of my colleagues, we have been preparing to carry out the annual exercise at Oban Airport which went Summer Timetable ’live’ at 10:30 on the 27th April. It involved a few local emergency Colonsay Abandoned services and others in a bid to provide an accurate simulation of an Village accident at the airport. During the period of the exercise, Oban Airport was closed for about 2 hours to all but emergency helicopters. We would Airlines of the Past - Logo like to apologise for any inconvenience this caused and we had the Quiz airport fully open by 13:00 closely followed by a real-time minor emergency. These exercises are conducted and reported back to the Customer Feedback 2013 CAA as part of our Licence conditions.