When Computers Became of Interest in Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faktaboks DASK OG REGNECENTRALEN I 50'Erne Var England Og USA for Alvor Begyndt at Eksperimentere Med Elektroniske Datamaskiner

PROSAbladet nr. 11 2002 Tekst og foto: Claus Thorhauge Danmarks første systemprogrammør Igennem et langt liv har Jørn Jensen været lykkelig begravet i maskinkode. Allerede inden Danmarks første computer, Dask, var færdigbygget havde den nybagte programmør udviklet og testet de første dele til operativsystemet. Eller kontrolprogrammer, som det hed dengang i 50'erne. Men han var også den første operatør på en dansk computer, ligesom han var ankermanden bag de første Algolcompilere. Og måske den sidste, der i bund og grund kan overskue, hvad der sker inde i en computer. Der er nogen hjemme – i enhver forstand. Det kan godt være, at det kniber med at huske detaljerne for den 77–årige Jørn Jensen, men ellers fejler hverken hovedet under det viltre kridhvide hår eller humøret noget. Selv siger han, at han aldrig har følt et egentligt arbejdspres. – Hele mit arbejdsliv har bestået i leg. Jeg føler mig lykkelig, fordi jeg har lavet noget, jeg synes er sjovt, forklarer Danmarks første nørd. Allerede inden Danmarks første computer, Dask, blev indviet i 1958, havde folkene bag fået øje på Jørn Jensens særlige talent for at programmere – eller kode, som det hed dengang. Dengang hed det heller ikke en computer, men en elektronisk datamaskine. Og Dask var den første, der blev konstrueret og bygget i Danmark. Baseret på radiorør og vandkøling direkte fra vandværket blev Dansk Aritmetisk Sekvens Kalkulator (Dask) installeret i en villa i Valby i slutningen af 50'erne. Monstret vejede tre–et–halvt ton, og gulvet i dagligstuen blev forstærket for at holde til den kraftige maskine, der kunne lægge to tal sammen med den imponerende hastighed af 56 mikrosekunder (1 AT = additionstid) og havde et RAM–lager på fem Kbyte. -

Volume 38, Number 09 (September 1920) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 9-1-1920 Volume 38, Number 09 (September 1920) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 38, Number 09 (September 1920)." , (1920). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/672 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE Presser’s Musical Magazine MUSIC COMPOSITION FOR WOMEN BY CARRE JACOBS-BOND ULTRA-MODERN MUSIC EXPLAINED BY PROFESSOR CHARLES QUEF KEYBOARD MASTERY BY CONSTANTIN STERNBERG WHY UNDERPAY THE MUSIC TEACHER? BY CHARLES E. WATT HOW HAYDN SUCCEEDED BY COMMENDATORE E. di PIRANI $2.00 A YEAR THE EjTUDE SEPTEMBER 1920 Page 577 This TRADE MARK 'Represenhs Lhe BEST Lhere is in Beautiful Balladv Smil/nThittOUGH ( Sacred - Secular ) Solos - Duets - Quartete r%gj THEY SONGS G;i? C / I* *V>* ' CAN AND MORE 5°*G „ / ARE I/S , BE OtWllTTltBOYQfMlNf S«S£„. &-*£? AT T: °A iJjev*. ri»e* '**». /PLAYED CONG «««** ON A>f 9 ■0 2-4, , PIANO Evening Brings Rest DjARD/ ' G^f„ And you /or ORGAN *e ' 50 Wes Tb*^tefi each like *5'”' / IDEAL FOR THIS IT I^^SSCE?* 'the HOME ACTUAL SIZE / 6 by 9 Inches CONCERT MAUMUSUNfUWaS-fiOOON'OHl SENT /and CHURCH on requeshy IF YOU LOVE A GOOD enclosej BALLAD 5 cents i H°WONETm in stan ( SACRED or SECULAR) . -

2006: Celebrating 75 Years of AI-History and Outlook: the Next 25

2006: Celebrating 75 years of AI - History and Outlook: the Next 25 Years∗ J¨urgen Schmidhuber TU Munich, Boltzmannstr. 3, 85748 Garching bei M¨unchen, Germany & IDSIA, Galleria 2, 6928 Manno (Lugano), Switzerland [email protected] - http://www.idsia.ch/∼juergen Abstract When Kurt G¨odel layed the foundations of theoretical computer science in 1931, he also introduced essential concepts of the theory of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Although much of subsequent AI research has focused on heuristics, which still play a major role in many practical AI applications, in the new millennium AI theory has finally become a full-fledged formal science, with important optimality results for embodied agents living in unknown environments, obtained through a combination of theory `ala G¨odel and probability theory. Here we look back at important milestones of AI history, mention essential recent results, and speculate about what we may expect from the next 25 years, emphasizing the significance of the ongoing dramatic hardware speedups, and discussing G¨odel-inspired, self- referential, self-improving universal problem solvers. 1 Highlights of AI History—From Godel¨ to 2006 Godel¨ and Lilienfeld. In 1931, 75 years ago and just a few years after Julius Lilien- feld patented the transistor, Kurt G¨odel layed the foundations of theoretical computer science (CS) with his work on universal formal languages and the limits of proof and computation [5]. He constructed formal systems allowing for self-referential state- arXiv:0708.4311v1 [cs.AI] 31 Aug 2007 ments that talk about themselves, in particular, about whether they can be derived from a set of given axioms through a computational theorem proving procedure. -

Gramophone, Film, Typewriter

EDITORS Timothy Lenoir and Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht GRAMOPHONE, FILM, TYPEWRITER FRIEDRICH A. KITTLER Translated, with an Introduction, by GEOFFREY WINT HROP-YOUNG AND MICHAEL WUTZ STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS STANFORD, CALIFORNIA The publication of this work was assisted by a subsidy from Inter Nationes, Bonn Gramophone, Film, Typewriter was originally published in German in I986 as Grammophon Film Typewriter, © I986 Brinkmann & Bose, Berlin Stanford University Press Stanford, California © I999 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University Printed in the United States of America erp data appear at the end of the book TRANSLATORS' ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A translation by Dorothea von Mucke of Kittler's Introduction was first published in October 41 (1987): 101-18. The decision to produce our own version does not imply any criticism of the October translation (which was of great help to us) but merely reflects our decision to bring the Introduction in line with the bulk of the book to produce a stylisti cally coherent text. All translations of the primary texts interpolated by Kittler are our own, with the exception of the following: Rilke, "Primal Sound," has been reprinted from Rainer Maria Rilke, Selected Works, vol. I, Prose, trans. G. Craig Houston (New York: New Directions, 1961), 51-56. © 1961 by New Directions Publishing Corporation; used with permis sion. The translation of Heidegger's lecture on the typewriter originally appeared in Martin Heidegger, Parmenides, trans. Andre Schuwer and Richard Rojcewicz (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1992), 80-81, 85-8 6. We would like to acknowledge the help we have received from June K. -

Early Nordic Compilers and Autocodes Peter Sestoft

Early Nordic Compilers and Autocodes Peter Sestoft To cite this version: Peter Sestoft. Early Nordic Compilers and Autocodes. 4th History of Nordic Computing (HiNC4), Aug 2014, Copenhagen, Denmark. pp.350-366, 10.1007/978-3-319-17145-6_36. hal-01301428 HAL Id: hal-01301428 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01301428 Submitted on 12 Apr 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Early Nordic Compilers and Autocodes Version 2.1.0 of 2014-11-17 Peter Sestoft IT University of Copenhagen Rued Langgaards Vej 7, DK-2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark [email protected] Abstract. The early development of compilers for high-level program- ming languages, and of so-called autocoding systems, is well documented at the international level but not as regards the Nordic countries. The goal of this paper is to provide a survey of compiler and autocode development in the Nordic countries in the early years, roughly 1953 to 1965, and to relate it to international developments. We also touch on some of the historical societal context. 1 Introduction A compiler translates a high-level, programmer-friendly programming language into the machine code that computer hardware can execute. -

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in the Journal of Functional Programming

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in the Journal of Functional Programming Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 14 May 2021 Version 1.04 Title word cross-reference $37.99 [Rag13]. $60.00 [Mil13]. $70 [Gam09]. $AU [Tho04a]. λ [AMR09, BFG97, BS96, Cro99, CH94b, CD96, DM05, GK96, Gol00, HD97, Hue94, KR97, Kam05, ØP97]. λν [BBLRD96]. λse [Gui00]. ! [HL96]. Π [KN96, DG02, GK96, Jef01, RH03]. -calculi [Kam05]. -calculus [AMR09, Cro99, CD96, DG02, DM05, GK96, Gol00, Gui00, HD97, Hue94, KR97, ØP97, RH03, Jef01]. -conversion [KN96]. -cube [BFG97]. -RED [GK96]. //www.pragprog.com [Hag11]. 0 [Bha09, Boi03, Boi12, Bud08, Ceb11, Ceb12, Der04, Hut94, Jon92b, Kar03, Kel03, Klu01, McK99, Mit95, San06, Sim07, Tho02, Tho04b, Vil07, dP01, vS00]. 0-13-184854-2 [Fou96]. 0-13-288788-6 [Fou96]. 0-13-722075-8 [Fou96]. 1 2 0-19-511306-3 [Tho02]. 0-201-39820-6 [Klu01]. 0-201-59604-0 [Rus03]. 0-262-06217-8 [Tah03a]. 0-262-19455-4 [Kar03]. 0-262-22069-5 [Gam09]. 0-262-51087-1 [Woo01]. 0-333-99285-7 [Han04]. 0-387-95349-3 [Der04]. 0-387-95391-4 [Tho04b]. 0-471-93844-0 [Mit95]. 0-471-99886-9 [Kel03]. 0-521-39022-2 [Fou96]. 0-521-41497-0 [Jon92b]. 0-521-44189-7 [Hut94]. 0-521-45520-0 [Klo01]. 0-521-48089-2 [O'D01]. -

Flows and Human Interferences

Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000. 25:53–88 Copyright c 2000 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved PHOSPHORUS IN THE ENVIRONMENT: Natural Flows and Human Interferences Vaclav Smil Department of Geography, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N2 Canada; e-mail: [email protected] Key Words biogeochemical cycling, phosphates, fertilizers, eutrophication ■ Abstract Phosphorus has a number of indispensable biochemical roles, but it does not have a rapid global cycle akin to the circulations of C or N. Natural mobilization of the element, a part of the grand geotectonic denudation-uplift cycle, is slow, and low solubility of phosphates and their rapid transformation to insoluble forms make the element commonly the growth-limiting nutrient, particularly in aquatic ecosystems. Human activities have intensified releases of P.By the year 2000 the global mobilization of the nutrient has roughly tripled compared to its natural flows: Increased soil erosion and runoff from fields, recycling of crop residues and manures, discharges of urban and industrial wastes, and above all, applications of inorganic fertilizers (15 million tonnes P/year) are the major causes of this increase. Global food production is now highly dependent on the continuing use of phosphates, which account for 50–60% of all P supply; although crops use the nutrient with relatively high efficiency, lost P that reaches water is commonly the main cause of eutrophication. This undesirable process affects fresh and ocean waters in many parts of the world. More efficient fertilization can lower nonpoint P losses. Although P in sewage can be effectively controlled, such measures are often not taken, and elevated P is common in treated wastewater whose N was lowered by denitrification. -

Cosmograph? What's A

Volunteer Information Exchange Sharing what we know with those we know Volume 2 Number 16 November 23, 2012 CHM's New Blog Contribute To The VIE Recent CHM Blog Entries Thanks to Doris Duncan and Lyle Bickley for their Kirsten Tashev keeps us up-to-date on our new CHM articles this month. What an amazing set of people Blog. Recent Entries are: are our volunteers. • 10/19 - Alex Lux “Little Green Men,” I had an opportunity to visit the IBM archives in New http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/little-green- York last month. It was occasioned by by question, men/ “What is a cosmograph?” See the article on page 2. • 10/24 - Dag Spicer A special visitor to CHM There will be more on “What I did on my vacation” in and his work on Squee: the Robot Squirrel! future issues. http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/squee-the- So, if you do anything that relates to the CHM while robot-squirrel/ you are on vacation, please remember the VIE. We • 10/26 - Karen Kroslowitz, need your stories to make the VIE vibrant. http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/preservation- conservation-restoration-whats-the-difference/ Please share your knowledge with your colleagues. Contribute to the VIE. • 10/31 - Chris Garcia http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/the-haunted- Jim Strickland [email protected] house/ • 11/2 - William Harnack about his trip to Blizzard Entertainment for the new Make Software exhibit in development, The VIE Cumulative Index is stored at: http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/my-gamer- http://s3data.computerhistory.org.s3.amazo soul-wept-with-epic-joy/ naws.com/chmedu/VIE- • 11/4 Marc Weber on his amazing trip to Kenya to 000_Cumulative_Topic_Index.pdf conduct research for the upcoming Make Software: Change the World! exhibit, http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/the-other- internet-part-1-masai-mara/ • 11/15 Alex Lux i n honor of Guinness World Record Day Nov. -

A Domain Specific Language and a First Step Towards the Realization of Situ

Situf : A Domain Specific Language and A First Step Towards the Realization of Situ Framework by Hua Ming A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Computer Science Program of Study Committee: Carl K. Chang, Major Professor Johnny Wong Simanta Mitra Jin Tian Ting Zhang Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright c Hua Ming, 2012. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3539397 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3539397 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013 . Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ii DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my families and friends, both in Beijing China and in Iowa United States. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .................................... v LISTOFFIGURES................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................... viii ABSTRACT ........................................ ix CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION . ........................ 1 1.1 Review of Situ framework .............................. 1 1.2 Declarative situations ................................ 1 1.3 A functional paradigm ................................ 3 1.4 Situf -based Environment ............................... 5 1.5 A glance view of the Situf environment ...................... 5 1.5.1 A retargetable environment ........................ -

Academic Catalog 2006-2007 Table of Contents

University of South Carolina Upstate Academic Catalog 2006-2007 Upstate University of South Carolina Academic Catalog 2006-2007 Table of Contents Academic Calendars ..............................................................................................................................4 The University .......................................................................................................................................6 Greenville Campus ..............................................................................................................................13 Admissions ...........................................................................................................................................16 Financial Aid ........................................................................................................................................25 Fees and Expenses ...............................................................................................................................37 Student and Diversity Affairs ...............................................................................................................41 Academic Regulations .........................................................................................................................47 Academic Programs .............................................................................................................................61 Honors Program ...................................................................................................................................69 -

A History of Compilers

A history of compilers Peter Sestoft [email protected] DIKU, University of Copenhagen 2014-02-21 www.itu.dk 1 Outline • What is a compiler? • A history of the history of ... • Early autoprogramming systems • The FORTRAN I compiler • Some Algol compilers • Lexing and parsing • Code generation • Intermediate languages • Optimization • (Flow analysis) • (Type systems) • (Compiler generators) • Recommended reading and sources • The nuclear origins of objects and classes www.itu.dk 3 What is a compiler (today)? for (int i=0; i<n; i++) LBB0_1: movl -28(%rbp), %eax // i sum += sqrt(arr[i]); clang movl -4(%rbp), %ecx // n cmpl %ecx, %eax C language source program jge LBB0_4 // if i >= n, return movslq -28(%rbp), %rax // i movq -16(%rbp), %rcx // address of arr[0] movsd (%rcx,%rax,8), %xmm0 // arr[i] callq _sqrt // sqrt movsd -24(%rbp), %xmm1 // sum addsd %xmm0, %xmm1 // sum + ... movsd %xmm1, -24(%rbp) // sum = ... movl -28(%rbp), %eax // i addl $1, %eax // i + 1 movl %eax, -28(%rbp) // i = ... jmp LBB0_1 // loop again x86 machine code From Aho et al et Aho From 4 A compiler in context Source language Dev. environment • Syntax • Editors • Types, semantics • Syntax highlighting • Libraries • Debuggers • Linkers Focus Compiler Runtime support Intermediate lang. • Lexing, parsing • Memory management • Instructions • Checking, types • Libraries • Types, semantics • Optimization • Debuggers • Libraries • Code generation Hardware Operating system • Instruction set • Process management • Memory hierarchy • Kernel functions • Peripherals www.itu.dk 5 Conceptual phases of a compiler From Aho et al et Aho From 6 Why "compiler" not "translator"? • Hopper: A Programmer's Glossary, 1 May 1954: Jones:1954:ASurvey • Hopper's A-2 compiler collected & inlined subroutines – In modern terminology: macro expansion • Later use: "algebraic compiler" to mean translator 7 A history of the history of .. -

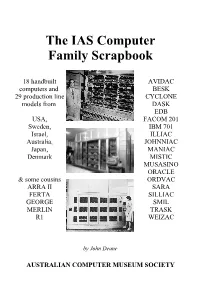

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook 18 handbuilt AVIDAC computers and BESK 29 production line CYCLONE models from DASK EDB USA, FACOM 201 Sweden, IBM 701 Israel, ILLIAC Australia, JOHNNIAC Japan, MANIAC Denmark MISTIC MUSASINO ORACLE & some cousins ORDVAC ARRA II SARA FERTA SILLIAC GEORGE SMIL MERLIN TRASK R1 WEIZAC by John Deane AUSTRALIAN COMPUTER MUSEUM SOCIETY The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook by John Deane Front cover: John von Neumann and the IAS Computer (Photo by Alan Richards, courtesy of the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study), Rand's JOHNNIAC (Rand Corp photo), University of Sydney's SILLIAC (photo courtesy of the University of Sydney Science Foundation for Physics). Back cover: Lawrence Von Tersch surrounded by parts of Michigan State University's MISTIC (photo courtesy of Michigan State University). The “IAS Family” is more formally known as Princeton Class machines (the Institute for Advanced Study is at Princeton, NJ, USA), and they were referred to as JONIACs by Klara von Neumann in her forward to her husband's book The Computer and the Brain. Photograph copyright generally belongs to the institution that built the machine. Text © 2003 John Deane [email protected] Published by the Australian Computer Museum Society Inc PO Box 847, Pennant Hills NSW 2120, Australia Acknowledgments My thanks to Simon Lavington & J.A.N. Lee for your encouragement. A great many people responded to my questions about their machines while I was working on a history of SILLIAC. I have been sent manuals, newsletters, web references, photos,