Analyzing the Perception of Support Services in Higher Education on the Academic Persistence of Black Male Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHORF HYPOTHESIS Temima Geula Fruchter

LINGUISTIC RELATIVITY AND UNIVERSALISM: A JUDEO-PHILOSOPHICAL RE-EVALUATION OF THE SAPIR- WHORF HYPOTHESIS Temima Geula Fruchter 2018 0 LINGUISTIC RELATIVITY AND UNIVERSALISM: A JUDEO-PHILOSOPHICAL RE-EVALUATION OF THE SAPIR-WHORF HYPOTHESIS By Temima Geula Fruchter 2012196057 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy in the Faculty of the Humanities at the University of the Free State June 2018 Promoter: Professor Pieter Duvenage 1 Contents Dedication ................................................................................................................................. 6 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Declaration ................................................................................................................................ 9 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 10 Notes ........................................................................................................................................ 12 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 15 How this Project Was Born ................................................................................................. 15 The Purpose of this Project ................................................................................................. -

Patriot Press April May 2019

@LibertyPublicat @libertyhspublications www.pinterest.com/tyearbook April/May 2019 Patriot Press News Team Volume 25: Issue 5 Liberty High School Talon Yearbook and Patriot Press Newspaper 6300 Independence Avenue, Bealeton, Virginia 22712 The Quinceañera Endures as a Meaningful Rite of Passage her brothers, sisters, cousins,and by Melissa Reyes that the Quinceañera is officially all the special people in her life ~Staff Reporter a young woman and that the doll and the people who she wants is officially her last toy. Another to share her special day with. very special ceremony is the coro- “I didn’t have have a nation. It’s when the Quinceañera Court of Honor because I just is given a crown and officially wanted a small party with just declared a princess to everybody my family. I wanted to be able that is present. The shoe ceremo- to talk to everyone in my family ny is where the Quinceañera’s and not just focus on dances,” father presents her with a pair said sophomore Katie Castro. of heels, officially meaning “I chose my Court with she is not a little girl anymore. family and friends I am close with,” The dances are a very said senior Wendy Velasquez. important part of Quinceañeras. “I was surprised I got They are not a requirement for picked to be a Chambelan of every party but they do make Elizabeth Padilla-Delgado poses for Honor because I wasn’t His- the night more fun and special. a fabulous photo session before panic,” said junior Khai Pham. There are many dances that a her Quinceañera. -

Baby Dedication Preparation Packet

BABY DEDICATION PREPARATION PACKET TABLE OF CONTENTS BABY DEDICATION 4 WHAT IS INFANT BAPTISM? 4 WHAT IS A BABY DEDICATION? 4 ARE BABY DEDICATIONS BIBLICAL? 5 WHAT HAPPENS DURING A BABY DEDICATION? 5 HOW DOES A PARENT SCHEDULE A BABY DEDICATION? 6 BABY DEDICATION CEREMONY 7 PRECEDENT OF PURPOSE OF DEDICATION 7 COVENANT OF PARENTS 7 THE ACT OF DEDICATION 8 APPLICATION TO ADULTS 8 PRESENTATION OF CERTIFICATE AND GIFTS 8 BABY DEDICATION INFORMATION FORM 9 ADOPTED JULY 31, 2019 BABY DEDICATION 2 Dear Friend: Your family is about to take one of the most important steps in your child’s life and we here at Bethel Church rejoice and celebrate with you. The materials enclosed in this packet will help you in preparation for this next step in your child’s spiritual journey. It is important that you to make full use of the information provided and jot down any questions you may wish to ask. This packet serves as a way for you to become acquainted with our theology about infant baptism and to provide some basic instructions about the baby dedication process. Please complete the "Baby Dedication Information Form” and return it to the Church Office. This provides us with information for a Dedication Certificate that we will mail to you. Please note dedications are not a sacrament of the church and may be done privately apart from the congregation on a Saturday afternoon or at other times in the family home. Parents may also schedule the dedication during the Sunday morning worship services. We look forward to hearing from you soon. -

The Circulation of Popular Dance on Youtube

Social Texts, Social Audiences, Social Worlds: The Circulation of Popular Dance on YouTube Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alexandra Harlig Graduate Program in Dance The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Harmony Bench, Advisor Katherine Borland Karen Eliot Ryan Skinner Copyrighted by Alexandra Harlig 2019 2 Abstract Since its premiere, YouTube has rapidly emerged as the most important venue shaping popular dance practitioners and consumers, introducing paradigm shifts in the ways dances are learned, practiced, and shared. YouTube is a technological platform, an economic system, and a means of social affiliation and expression. In this dissertation, I contribute to ongoing debates on the social, political, and economic effects of technological change by focusing on the bodily and emotional labor performed and archived on the site in videos, comments sections, and advertisements. In particular I look at comments and fan video as social paratexts which shape dance reception and production through policing genre, citationality, and legitimacy; position studio dance class videos as an Internet screendance genre which entextualizes the pedagogical context through creative documentation; and analyze the use of dance in online advertisements to promote identity-based consumption. Taken together, these inquiries show that YouTube perpetuates and reshapes established modes and genres of production, distribution, and consumption. These phenomena require an analysis that accounts for their multivalence and the ways the texts circulating on YouTube subvert existing categories, binaries, and hierarchies. A cyclical exchange—between perpetuation and innovation, subculture and pop culture, amateur and professional, the subversive and the neoliberal—is what defines YouTube and the investigation I undertake in this dissertation. -

Out with the Old, in with the New Congratulations Semesters Are a Thing of the Past at Milton High Do You Like the Trimester Schedule? School

What’s Inside? Sports Tech & Entertainment People Community Red Hawk gymnasts See who is Check-in with former Learn how to have are anxious for interested in the MHS Social Studies a COVID-friendly another successful new iPhone 12 teacher, Mr. Crofts Thanksgiving p. 11 season p. 4 p. 7 p. 2 Finding the Dancing Turkeys Throughout this edition there are 10 hidden dancing turkeys. Find them all! Milton High School Milton, WI Vol. 36, Issue 2 We’re online! November 2020 Donald Trumped? Joseph Biden has been pronounced the winner of the 2020 election along An electronic version with his running mate, Vice-President elect Kamala Harris. of MHS Today can be found on the school After one of the most As of November 11, Biden sits with the Trump administration, trying to issues in the US, including de- influential elections 279 electoral college votes, according say that voters were held to different bates over topics like education webpage under in the country’s his- to NBC. He is also sitting just above standards based on how they voted funding, COVID-19 response, tory, Joseph Biden has 77 million individual votes, mak- and to get the state’s votes invalidated. “News and been named the future ing him the candidate with the most “I think that he (Trump) is going immigration, healthcare, taxes, Announcements” Madison President of the United individual votes in the history of US to do a great job of making people and several other social and Manor States. The former vice- history. North Carolina, Georgia, and angry,” said Renee Steive, a MHS civil rights issues. -

Abingtonian – December2018

Abington Senior High School, Abington, PA, 19001 December 2018 Groundbreaking News By Joey Nolan On November 2nd, Abington Senior High School held a groundbreaking ceremony for the start of construction of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Center for Science and Technology. Th e event was held where the entrance to the new building will be, along Ghost Road. Th e renovations will cost just over $104 million, with $25 million coming from a donation by Abington alumnus, Steven A Schwarzman. I attended this ceremony, and I can honestly say it went off without a hitch. Abington’s student body president, Josiah Campbell, delivered an excellent speech on behalf of the students, followed by some words from former superintendent, Dr. Amy Sichel, who was proud to have her fi nal act in her position be to initiate this construction, before passing her position along to Dr. Fecher. Th e opening is anticipated to be in the fall of 2020, with a projected completion date in 2022. Th e construction will usher in not only the new science wing, but more art and general classroom space, as well as an auxiliary gymnasium, a career center, a new cafeteria, and of course, what we are all looking most forward to, air conditioning. Th is will be the fi rst major renovation on the building in nearly two decades. Th is addition also comes with the migration of the freshme n in to the newly named Abington High School, and the 6th graders in to the Junior High School. Th e construction and reconfi gured grade spans pave the way for a reimagined curriculum at Abington, implementing innovative programming focused on the skills needed to compete in the evolving workforce and preparing students to face the nation’s fastest-growing industries and jobs of the future. -

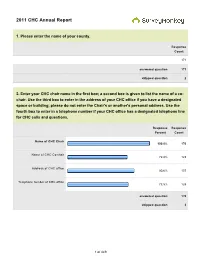

2011 CHC Annual Report

2011 CHC Annual Report 1. Please enter the name of your county. Response Count 171 answered question 171 skipped question 2 2. Enter your CHC chair name in the first box; a second box is given to list the name of a co- chair. Use the third box to enter in the address of your CHC office if you have a designated space or building; please do not enter the Chair's or another's personal address. Use the fourth box to enter in a telephone number if your CHC office has a designated telephone line for CHC calls and questions. Response Response Percent Count Name of CHC Chair 100.0% 170 Name of CHC Co-chair 72.4% 123 Address of CHC office 80.6% 137 Telephone number of CHC office 73.5% 125 answered question 170 skipped question 3 1 of 449 3. Enter the name of the person entering in report information. Response Count 171 answered question 171 skipped question 2 4. Please provide the name and email address for the individual who can be contacted to answer questions about this report. If the individual does not use email, please provide a valid telephone number. Response Count 171 answered question 171 skipped question 2 5. How many individuals are currently appointed to your CHC? Please enter numbers for your answer; do not use symbols or text. Response Response Response Average Total Count # of CHC appointees 21.12 3,591 170 answered question 170 skipped question 3 2 of 449 6. How many volunteer hours were contributed to CHC meeting, projects, and programs in 2011? Please enter numbers for your answer; do not use symbols or text. -

All Lil Wayne Album Download Zip Lil Wayne & DJ Drama – Dedication 4

all lil wayne album download zip Lil Wayne & DJ Drama – Dedication 4. Dedication 4 is an official mixtape by Lil Wayne hosted by DJ Drama, which was released in 2012. There are a total of 15 tracks on the tape and the majority of the songs is Weezy rapping over different music artists’ instrumentals. You can read the lyrics here and view the tracklist plus grab the download link below: 1. So Dedicated featuring Birdman 2. Same Damn Tune 3. Cashed Out 4. No Worries featuring Detail 5. Mercy featuring Nicki Minaj 6. Burn 7. Amen featuring Boo 8. Get Smoked featuring Lil Mouse 9. My Homies Still (Remix) featuring Jae Millz, Gudda Gudda, and Young Jeezy 10. Green Ranger featuring J. Cole 11. I Don’t Like 12. No Lie 13. Magic featuring Flow 14. Wish You Would 15. A Dedication. Share and Enjoy: Social Networks. Subscribe Now. Enter your e-mail address above to get Lil Wayne updates sent to you via e-mail. LIL WAYNE - FUNERAL Download. Lil Wayne has been battling a lot of leaks lately including the tracklist of his upcoming album, Funeral. The release date for Lil Wayne's Funeral album is here. On Thursday (Jan. 23), Weezy announced that his new project will drop next Friday (Jan. 31). He used his Twitter account to make the announcement, which includes a link to the shop where you can buy the new project. This announcement comes nearly four years after he first teased the project during his appearance on The Nine Club podcast in 2016. -

Lil Wayne Dedication 6 Free Mp3 Download Lil Wayne & DJ Drama – Dedication 4

lil wayne dedication 6 free mp3 download Lil Wayne & DJ Drama – Dedication 4. Dedication 4 is an official mixtape by Lil Wayne hosted by DJ Drama, which was released in 2012. There are a total of 15 tracks on the tape and the majority of the songs is Weezy rapping over different music artists’ instrumentals. You can read the lyrics here and view the tracklist plus grab the download link below: 1. So Dedicated featuring Birdman 2. Same Damn Tune 3. Cashed Out 4. No Worries featuring Detail 5. Mercy featuring Nicki Minaj 6. Burn 7. Amen featuring Boo 8. Get Smoked featuring Lil Mouse 9. My Homies Still (Remix) featuring Jae Millz, Gudda Gudda, and Young Jeezy 10. Green Ranger featuring J. Cole 11. I Don’t Like 12. No Lie 13. Magic featuring Flow 14. Wish You Would 15. A Dedication. Share and Enjoy: Social Networks. Subscribe Now. Enter your e-mail address above to get Lil Wayne updates sent to you via e-mail. Lil Wayne & DJ Drama – Dedication. Dedication is an official mixtape by Lil Wayne hosted by DJ Drama, which was released in 2005. There are a total of 29 tracks on the tape and it is the first mixtape in the Dedication trilogy. You can view the tracklist and download link below: 1. Dedication 2. Intro 3. Motivation 4. Over Here featuring Boo 5. Wayne Convos 6. U Gon’ Love Me 7. Down And Out 8. Wayne Explains His Deal 9. Like Dat 10. Nah This Ain’t The Remix 11. Bass Beat featuring Currency 12. -

JSEL Volume 12, Issue 2

Volume 12, Number 2 Spring 2021 Contents ARTICLES Chopped & Screwed: Hip Hop from Cultural Expression to a Means of Criminal Enforcement Taifha Natalee Alexander............................................ 211 It’s Worth a Shot: Can Sports Combat Racism in the United States? David A. Grenardo ................................................ 237 A Defense of Public Financing in a Time of Economic Hardship, Social Unrest, and Athlete Advocacy Ryan Gribbin-Burket ............................................... 319 #IAMAROBOT: Is it Time for the Federal Trade Commission to Rethink its Approach to Virtual Influencers in Sports, Entertainment, and the Broader Market? Jim Masteralexis, Steve McKelvey, and Keevan Statz ...................... 353 Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law Student Journals Office, Harvard Law School 1541 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-3146; [email protected] www.harvardjsel.com U.S. ISSN 2153-1323 The Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law is published semiannually by Harvard Law School students. Submissions: The Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law welcomes articles from professors, practitioners, and students of the sports and entertainment industries, as well as other related disciplines. Submissions should not exceed 25,000 words, including footnotes. All manuscripts should be submitted in English with both text and footnotes typed and double-spaced. Footnotes must conform with The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (21st ed.), and authors should be prepared to supply any cited sources upon request. All manu- scripts submitted become the property of the JSEL and will not be returned to the author. The JSEL strongly prefers electronic submissions through the Scholastica online submission system. Submissions may also be sent via email to [email protected] or in hard copy to the address above. -

Publications Excluded Thru 06-30-19

Arizona DOC PUBLICATIONS EXCLUDED THRU 06-30-19 Publication Title Publisher Publicati Publication Publicatio Publicatio Publication Complex Complex OPR OPR on Type Date n Volume n Number ISBN Dispositio Dispositi Disposition Disposition n on Date Date ^^CONEJO - CITY OF LOS ANGELES SL CD 2007 2 804227190625 Excluded 3/19/2019 Excluded 6/27/2019 ENTERTAINM ENT ^^CONEJO - Written in Blood The Prime CD 2012 885767407978 Excluded 3/19/2019 Excluded 6/27/2019 Suspect ^^Field & Stream Magazine june july 2019 124 2 Excluded 6/3/2019 Excluded 6/26/2019 ^^WHITETAIL JOURNAL Magazine MAY/JUNE 2019 28 3 Excluded 5/25/2019 Excluded 6/26/2019 ^^Crazy Crow Magazine 2019 36 Excluded 6/4/2019 Excluded 6/25/2019 ^^Outdoor Life Magazine summer 2019 226 3 Excluded 6/10/2019 Excluded 6/25/2019 ^^LIL BABY & GUNNA / DRIP HARDER QUALITY CD 2018 602577209598 Excluded 2/6/2019 Excluded 6/25/2019 CONTROL MUSIC THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF SKULLS 2014 978-0-7624-5463-1 Excluded 11/17/2017 Excluded 6/25/2019 ^^WHAT TO EXPECT WHEN YOU'RE ANDREWS Book 2012 5th Edition 9780761187486 / Excluded 6/3/2019 Excluded 6/21/2019 EXPECTING MCMEEL 9781449418465 ^^2 chainz - rap or go to the league 2019 602577497391 Excluded 4/8/2019 Excluded 6/21/2019 ^^I DECLARE WAR - I DECLARE WAR ARTERY CD 2011 793018313827 Excluded 6/4/2019 Excluded 6/21/2019 RECORDINGS ^^JUICE WRLD / DEATH RACE FOR LOVE GRADE A CD 2019 6025774480379 Excluded 4/5/2019 Excluded 6/20/2019 PRODUCTION S ^^SKI MASK THE SLUMP GOD - STOKELEY CD 2019 602577361739 Excluded 5/3/2019 Excluded 6/20/2019 ^^HEAVY METAL Magazine -

Dedication 6 Album Download Zip Lil Wayne & Young Money – Young Money the Mixtape Vol

dedication 6 album download zip Lil Wayne & Young Money – Young Money The Mixtape Vol. 1. Young Money The Mixtape Volume 1 is a two-disc official mixtape by Lil Wayne and his Young Money crew, which was released in 2005. There are a total of 28 tracks on the tape (14 on CD1 and 14 on CD2) . You can view the tracklist and download link below: DISC 1 1. Dis Is How We Do with Boo, Mack Maine and Currency 2. Lean Back with Currency 3. Ashanti Remix – Currency 4. Rep Yo Hood with Mack Maine 5. Politician with Currency 6. We Pimpin’, Y’all Simpin’ with Boo, Currency and Mack Maine 7. Fetish with Currency, Mack Maine and Boo 8. You’re Gonna Love Me 9. Breathe – Currency 10. No Problems with Currency, Mack Maine and Boo 11. Smoke, Drank with Mack Maine and Boo 12. Bone Mix with Currency, Boo and Mack Maine 13. Two Words with Dizzy 14. New York with Currency, Boo and Mack Maine DISC 2 1. Mr. Biggs 2. Young Money with Currency, Boo and Mack Maine 3. Slim Thug with Currency and Mack Maine 4. My City – Mack Maine 5. Knuck If You Buck Freestyle with Mack Maine and Currency 6. Hold U Down – Currency, Boo and Mack Maine 7. Pop That Thang with Boo, Currency and Mack Maine 8. Why U Lookin’ At Me – Currency 9. Drop It Like Its Hot 10. Mama Gave Me 11. Killa Cam Freestyle 12. Rest In Peace 13. I Call It Whateva 14. 2Pac Dedication. The password for the .rar file is: www.lilwaynehq.com | More info on extracting .rar files can be found on the mixtape page Share and Enjoy: Social Networks.