JSEL Volume 12, Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NFL Draft 2019 Grades: Evaluating the Broncos and Every Other Team’S Picks by Ryan O’Halloran Denver Post April 29, 2019

NFL draft 2019 grades: Evaluating the Broncos and every other team’s picks By Ryan O’Halloran Denver Post April 29, 2019 A team-by-team recap of this weekend’s NFL draft: NFC Arizona Cardinals A — The Cardinals selected immediate starters/contributors with their first five picks: QB Kyler Murray, CB Byron Murphy, WR Andy Isabella, DE Zach Allen and WR Hakeem Butler. With play-caller/coach Kliff Kingsbury, the Cardinals may not be successful, but they’ll be interesting. Atlanta Falcons C-plus — The Falcons ignored cornerback until round 5 (Jordan Miller). First-rounders Chris Lindstrom (No. 14) and Kaleb McGary (No. 31 after a trade-up) will start at right guard and right tackle, respectively. Carolina Panthers B — Liked what the Panthers did early. DE Brian Burns will team with veteran Bruce Irvin to replace Julius Peppers. LT Greg Little will get a chance to beat out 2017 second-round pick Taylor Moton and QB Will Grier could stop the revolving back-up spot. Chicago Bears D — If you factor in the Khalil Mack trade (which costs them a first-round pick), the grade would be different. But the Bears had only five picks (one in the first 125). RB David Montgomery (round 3) will back up Mike Davis. Dallas Cowboys C — No first-round pick because of the Amari Cooper trade. The Cowboys had nine picks, but only two in the top 116. They chose two defensive ends (Joe Jackson and Jalen Jelks) and running backs (Tony Pollard and Mike Weber) apiece. Detroit Lions C-minus— Tough to be fired up about anything the Lions did after tight end T.J. -

Uradni List C 187 E Zvezek 51 Evropske Unije 24

ISSN 1725-5244 Uradni list C 187 E Zvezek 51 Evropske unije 24. julij 2008 Slovenska izdaja Informacije in objave Obvestilo št. Vsebina Stran IV Informacije INFORMACIJE INSTITUCIJ IN ORGANOV EVROPSKE UNIJE Evropski parlament ZASEDANJE 2007—2008 Seje: 3. september—6. september 2007 Ponedeljek, 3. september 2007 (2008/C 187 E/01) ZAPISNIK POTEK SEJE . 1 1. Nadaljevanje zasedanja . 1 2. Izjava predsednika . 1 3. Sprejetje zapisnika predhodne seje . 2 4. Predložitev dokumentov . 2 5. Sestava Parlamenta . 7 6. Sestava odborov in delegacij . 8 7. Podpis aktov, sprejetih v postopku soodločanja . 8 8. Predložitev skupnih stališč Sveta ............................................... 8 9. Posredovanje besedil sporazumov s strani Sveta . 8 10. Peticije . 9 11. Prerazporeditev sredstev . 14 12. Vprašanja za ustni odgovor in pisne izjave (predložitev).............................. 15 13. Nadaljnje obravnavanje stališč in resolucij Parlamenta . 16 14. Razpored dela . 16 15. Enominutni govori o zadevah političnega pomena . 16 SL (Nadaljevanje) Obvestilo št. Vsebina (nadaljevanje) Stran 16. Gozdni požari v Grčiji, njihove posledice in ugotovitve glede ukrepov za preprečevanje in opozarjanje (razprava) . 16 17. Boljša pravna ureditev – Boljša priprava zakonodaje 2005: načeli subsidiarnosti in sorazmernosti – Poenostavitev zakonodajnega okolja – Uporaba „mehkega prava“ (razprava) . 17 18. Poročilo o dejavnosti EURESa za obdobje 2004–2005: skupnemu evropskemu trgu dela naproti (razprava) . 18 19. Dnevni red naslednje seje . 19 20. Zaključekseje ............................................................ 19 SEZNAM NAVZOČIH .......................................................... 20 Torek, 4. september 2007 (2008/C 187 E/02) ZAPISNIK POTEK SEJE . 22 1. Otvoritev seje . 22 2. Razprava o primerih kršitev človekovih pravic, demokracije in načela pravne države (vloženi predlogi resolucij) . 22 3. Revizija enotnega trga (razprava) . 23 4. Statut družbe v zasebni lasti, pravo gospodarskih družb (razprava) . -

Meet Warner's Matt Signore Bandtwango Funds The

February 13, 2017, Issue 536 Meet Warner’s Matt Signore Named as incoming Warner Music Nashville COO as far back as July, Matt Signore brings 25 years of record busi- ness experience, a long history with WMN Chairman/CEO John Esposito and a few other Nashville connections to the role he started Jan. 1. CA: How did you end up in the music business? MS: I worked as a CPA in New York for a big accounting firm. Back in that day with those jobs, you hoped one of your clients would hire you. I had a friend who worked on the acquisition of Island Records by Polygram, went there and basically had a job for me. I was 26 years old, got a $3,000 raise and I could wear jeans to work. I came home and said, “I think I want to do this.” I wasn’t a musician and didn’t want to be in the music business, necessarily. But I went to work for Matt Signore Island and ultimately Island/Def Jam on the business side. How did you meet Espo? Exclusive Club: AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am tournament winner In 1994, he was the head of catalog sales at Polygram. He was Jordan Spieth (l) and partner Jake Owen celebrate a big the guy trying to get labels to clear things for catalog work, and my weekend on the links. In addition to the pair placing third in boss was a pain in the ass. His first memory of me was as the fi- the Pro-Am, Owen was honored with the Arnie Award, which nance guy at Island who helped him get stuff done. -

Debates ROSS WATTERS

Vol. 90 Issue 53 December 8, 2011 CSUF Parking Woes effect Fullerton Residents Spark of love Looking for something to do during the Watch the holiday break? Why not give back to the Daily Titan community. There are several volunteer opportunities within Orange County. News in 3 The OC Toy Collaborative is one. Get up- Scan to view ONLINE Scan to view EXCLUSIVES to-date dailytitan.com/ dailytitan.com/ coverage on sparkoflovef11 dtn312811 top campus news stories. dailytitan.com The Student Voice of California State University, Fullerton Renovating ROSS WATTERS {debates Daily Titan Heritage and culture–these are values the people on Fourth Street in Santa Ana pride themselves on. From restaurants, to shops, to art centers, to open marketplaces where different fruits and vegetables are sold, it is embedded with authentic Latino culture. However, many are looking to renovate this area and bring in new stores to pick up struggling businesses and “clean up the area.” Fourth Street in Santa Ana has been the hub of Latino business and culture for decades. Here most business signs are in Spanish. They sell authentic clothing, food and art that represent Latino culture. But with pressure from the economy to bring the imminent threat of “gentrification,” many long time Latino businesses are be- ing forced out. See GENT, page 2 WILLIAM CAMARGO / Daily Titan Canchola is driven to succeed Holidays welcome SUSANA COBO back NBA season Daily Titan PATRICK CORBET economics and labor law to a much Don’t smile. Daily Titan larger degree than your average Cal She laughs and questions, “How State Fullerton student. -

Download PDF Here

刀䔀倀伀刀吀 伀䘀 吀䠀䔀 䤀一吀䔀刀一䄀吀䤀伀一䄀䰀 䌀伀䴀䴀䤀匀匀䤀伀一 伀䘀 䤀一儀唀䤀刀夀 伀一 匀夀匀吀䔀䴀䤀䌀 刀䄀䌀䤀匀吀 倀伀䰀䤀䌀䔀 嘀䤀伀䰀䔀一䌀䔀 䄀䜀䄀䤀一匀吀 倀䔀伀倀䰀䔀 伀䘀 䄀䘀刀䤀䌀䄀一 䐀䔀匀䌀䔀一吀 䤀一 吀䠀䔀 唀一䤀吀䔀䐀 匀吀䄀吀䔀匀 䴀䄀刀䌀䠀 ㈀ ㈀ Photo details: Row 1, left to right: Aaron Campbell, Alberta Spruill, Andrew Kearse, Antonio Garcia Jr, Barry Gedeus, Botham Shem Jean, Breonna Taylor. Row 2, left to right: Casey Goodson, Clinton Allen, Damian Daniels, Daniel Prude, Darius Tarver, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray. Row 3, left to right, George Floyd, Henry Glover, Jacob Blake, Jason Harrison, Jayvis Benjamin, Jeffery Price, Jimmy Atchison, Jordan Baker. Row 4, left to right: Juan May, Kayla Moore, Linwood Lambert, Malcolm Ferguson, Manuel Elijah Ellis, Marquise Jones, Michael Brown, Momodou Lamin Sisay Row 5, left to right: Mubarak Soulemane, Nathaniel Pickett II, Ousmane Zongo, Patrick Dorismond, Patrick Warren, Sr, Ramarley Graham, Sean Bell Row 6, left to right: Shem Walker, Shereese Francis, Tamir Rice, Tarika Wilson, Tashii Farmer Brown, Tyrone West, Vincent Truitt Not pictured: Richie Lee Harbison REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SYSTEMIC RACIST POLICE VIOLENCE AGAINST PEOPLE OF AFRICAN DESCENT IN THE UNITED STATES MArcH 2021 REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SYSTEMIC RACIST POLICE VIOLENCE AGAINST PEOPLE OF AFRICAN DESCENT IN THE U.S. COMMISSIONERS Professor Sir Hilary Beckles, Barbados Professor Niloufer Bhagwat, India Mr. Xolani Maxwell Boqwana, South Africa Professor Mireille Fanon-Mendès France, France Dr. Arturo Fournier Facio, Costa Rica Judge Peter Herbert OBE, UK Ms. Hina Jilani, Pakistan Professor Rashida Manjoo, South Africa Professor Osamu Niikura, Japan Sir Clare K. Roberts, QC, Antigua and Barbuda Mr. Bert Samuels, Jamaica Mr. Hannibal Uwaifo, Nigeria RAPPORTEURS Professor Horace Campbell, United States Professor Marjorie Cohn, United States Ms. -

Edition 2017

YEAR-END EDITION 2017 HHHHH # OVERALL LABEL TOP 40 LABEL RHYTHM LABEL REPUBLIC RECORDS HHHHH 2017 2016 2015 2014 GLOBAL HEADQUARTERS REPUBLIC RECORDS 1755 BROADWAY, NEW YORK CITY 10019 REPUBLIC #1 FOR 4TH STRAIGHT YEAR Atlantic (#7 to #2), Interscope (#5 to #3), Capitol Doubles Share Republic continues its #1 run as the overall label leader in Mediabase chart share for a fourth consecutive year. The 2017 chart year is based on the time period from November 13, 2016 through November 11, 2017. In a very unique year, superstar artists began to collaborate with each other thus sharing chart spins and label share for individual songs. As a result, it brought some of 2017’s most notable hits including: • “Stay” by Zedd & Alessia Cara (Def Jam-Interscope) • “It Ain’t Me” by Kygo x Selena Gomez (Ultra/RCA-Interscope) • “Unforgettable” by French Montana f/Swae Lee (Eardrum/BB/Interscope-Epic) • “I Don’t Wanna Live Forever” by ZAYN & Taylor Swift (UStudios/BMR/RCA-Republic) • “Bad Things” by MGK x Camila Cabello (Bad Boy/Epic-Interscope) • “Let Me Love You” by DJ Snake f/Justin Bieber (Def Jam-Interscope) • “I’m The One” by DJ Khaled f/Justin Bieber, Quavo, Chance The Rapper & Lil Wayne (WTB/Def Jam-Epic) All of these songs were major hits and many crossed multiple formats in 2017. Of the 10 Mediabase formats that comprise overall rankings, Republic garnered the #1 spot at two formats: Top 40 and Rhythmic, was #2 at Hot AC, and #4 at AC. Republic had a total overall chart share of 15.6%, a 23.0% Top 40 chart share, and an 18.3% Rhythmic chart share. -

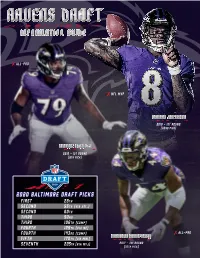

Information Guide

INFORMATION GUIDE 7 ALL-PRO 7 NFL MVP LAMAR JACKSON 2018 - 1ST ROUND (32ND PICK) RONNIE STANLEY 2016 - 1ST ROUND (6TH PICK) 2020 BALTIMORE DRAFT PICKS FIRST 28TH SECOND 55TH (VIA ATL.) SECOND 60TH THIRD 92ND THIRD 106TH (COMP) FOURTH 129TH (VIA NE) FOURTH 143RD (COMP) 7 ALL-PRO MARLON HUMPHREY FIFTH 170TH (VIA MIN.) SEVENTH 225TH (VIA NYJ) 2017 - 1ST ROUND (16TH PICK) 2020 RAVENS DRAFT GUIDE “[The Draft] is the lifeblood of this Ozzie Newsome organization, and we take it very Executive Vice President seriously. We try to make it a science, 25th Season w/ Ravens we really do. But in the end, it’s probably more of an art than a science. There’s a lot of nuance involved. It’s Joe Hortiz a big-picture thing. It’s a lot of bits and Director of Player Personnel pieces of information. It’s gut instinct. 23rd Season w/ Ravens It’s experience, which I think is really, really important.” Eric DeCosta George Kokinis Executive VP & General Manager Director of Player Personnel 25th Season w/ Ravens, 2nd as EVP/GM 24th Season w/ Ravens Pat Moriarty Brandon Berning Bobby Vega “Q” Attenoukon Sarah Mallepalle Sr. VP of Football Operations MW/SW Area Scout East Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Player Personnel Analyst Vincent Newsome David Blackburn Kevin Weidl Patrick McDonough Derrick Yam Sr. Player Personnel Exec. West Area Scout SE/SW Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Quantitative Analyst Nick Matteo Joey Cleary Corey Frazier Chas Stallard Director of Football Admin. Northeast Area Scout Pro Scout Player Personnel Assistant David McDonald Dwaune Jones Patrick Williams Jenn Werner Dir. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums God's Plan Look Alive the Greatest Showman OST Heartbreak on a Full Moon 1 Drake 21 Blocboy JB Feat

12 March 2018 CHART #2129 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums God's Plan Look Alive The Greatest Showman OST Heartbreak On A Full Moon 1 Drake 21 BlocBoy JB feat. Drake 1 The Greatest Showman Ensemble 21 Chris Brown Last week 1 / 7 weeks Platinum / CashMoney/Universal Last week 22 / 3 weeks OvoSound/Warner Last week 1 / 11 weeks Gold / Atlantic/Warner Last week 22 / 19 weeks RCA/SonyMusic Psycho Candy Paint Divide Doo-Wops And Hooligans 2 Post Malone feat. Ty Dolla $ign 22 Post Malone 2 Ed Sheeran 22 Bruno Mars Last week 2 / 2 weeks Republic/Universal Last week 20 / 16 weeks Platinum / Republic/Universal Last week 3 / 53 weeks Platinum x6 / Asylum/Warner Last week 26 / 135 weeks Platinum x6 / WEA/Warner All The Stars Havana Black Panther: The Album OST Hope World 3 Kendrick Lamar And SZA 23 Camila Cabello feat. Young Thug 3 Various 23 j-hope Last week 3 / 8 weeks Gold / TopDawg/Interscope/Univ... Last week 21 / 28 weeks Platinum x2 / Simco/SonyMusic Last week 2 / 4 weeks TopDawg/Interscope/Universal Last week - / 1 weeks BigHit/LoenEntertainment Mine Say Something 24K Magic Revival 4 Bazzi 24 Justin Timberlake And Chris Stapleto... 4 Bruno Mars 24 Eminem Last week 4 / 5 weeks Gold / ZZZEntertainment/Warner Last week 26 / 5 weeks RCA/SonyMusic Last week 5 / 68 weeks Platinum / Atlantic/Warner Last week 24 / 12 weeks Gold / Shady/Interscope/Universa... Love Lies Closer Six60 EP Day69 5 Khalid And Normani 25 Six60 5 Six60 25 6ix9ine Last week 8 / 3 weeks RCA/SonyMusic Last week 23 / 19 weeks Platinum / Massive/Universal Last week 4 / 16 weeks Gold / Massive/Universal Last week 15 / 2 weeks TenThousandProjects/Universal IDGAF Woke Up Late Stoney Melodrama 6 Dua Lipa 26 DRAX Project feat. -

I'm Gonna Keep Growin'

always bugged off of that like he always [imi tated] two people. I liked the way he freaked that. So on "Gimme The Loot" I really wanted to make people think that it was a different person [rhyming with me]. I just wanted to make a hot joint that sounded like two nig gas-a big nigga and a Iii ' nigga. And I know it worked because niggas asked me like, "Yo , who did you do 'Gimme The Loot' wit'?" So I be like, "Yeah, well, my job is done." I just got it from Slick though. And Redman did it too, but he didn't change his voice. What is the illest line that you ever heard? Damn ... I heard some crazy shit, dog. I would have to pick somethin' from my shit, though. 'Cause I know I done said some of the most illest rhymes, you know what I'm sayin'? But mad niggas said different shit, though. I like that shit [Keith] Murray said [on "Sychosymatic"]: "Yo E, this might be my last album son/'Cause niggas tryin' to play us like crumbs/Nobodys/ I'm a fuck around and murder everybody." I love that line. There's shit that G Rap done said. And Meth [on "Protect Ya Neck"]: "The smoke from the lyrical blunt make me ugh." Shit like that. I look for shit like that in rhymes. Niggas can just come up with that one Iii' piece. Like XXL: You've got the number-one spot on me chang in' the song, we just edited it. -

WHORF HYPOTHESIS Temima Geula Fruchter

LINGUISTIC RELATIVITY AND UNIVERSALISM: A JUDEO-PHILOSOPHICAL RE-EVALUATION OF THE SAPIR- WHORF HYPOTHESIS Temima Geula Fruchter 2018 0 LINGUISTIC RELATIVITY AND UNIVERSALISM: A JUDEO-PHILOSOPHICAL RE-EVALUATION OF THE SAPIR-WHORF HYPOTHESIS By Temima Geula Fruchter 2012196057 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy in the Faculty of the Humanities at the University of the Free State June 2018 Promoter: Professor Pieter Duvenage 1 Contents Dedication ................................................................................................................................. 6 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Declaration ................................................................................................................................ 9 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 10 Notes ........................................................................................................................................ 12 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 15 How this Project Was Born ................................................................................................. 15 The Purpose of this Project ................................................................................................. -

Istar 2011 – Proceedings of the 5Th International I* Workshop

iStar 2011 – Proceedings of the 5th International i* Workshop 29-30 th August, 2011 Trento, Italy http://www.cin.ufpe.br/~istar11/ Jaelson Castro Xavier Franch John Mylopoulos Eric Yu (eds.) a CEUR Workshop Proceedings, ISSN 1613-0073 © 2011 for the individual papers by the papers' authors. Copying permitted for private and academic purposes. This volume is published and copyrighted by its editors. Index Preface Keynote talk. Governing Sociotechnical Systems. Munindar P. Singh , p. 1 Scientific Papers Session 1. Framework Evaluation 1. Eight Deadly Sins of GRL . Gunter Mussbacher, Daniel Amyot, Patrick Heymans , p. 2-7 2. iStarML: Principles and Implications. Carlos Cares , Xavier Franch , p. 8-13 3. Empirical Evaluation of Tropos4AS Modelling. Mirko Morandini, Anna Perini, Alessandro Marchetto , p. 14-19 Session 2. Model Analysis and Evaluation 4. Detecting Judgment Inconsistencies to Encourage Model Iteration in Interactive i* Analysis. Jennifer Horkoff, Eric Yu , p. 20-25 5. Towards a Declarative, Constraint-Oriented Semantics with a Generic Evaluation Algorithm for GRL. Hao Luo, Daniel Amyot , p. 26-31 6. A Flexible Approach for Validating i* Models. Ralf Laue, Arian Storch , p. 32-36 Session 3a. Ontologies and Foundations 7. Ontological Analysis of Means-End Links. Xavier Franch, Renata Guizzardi, Giancarlo Guizzardi, Lidia López , p. 37-42 8. Supporting i* Model Integration through an Ontology-based Approach. Karen Najera, Anna Perini, Alicia Martínez, Hugo Estrada , p. 43-48 9. The Mysteries of Goal Decomposition. Scott Munro, Sotirios Liaskos, Jorge Aranda , p. 49-54 Session 3b. Enterprise and Software Architectures 10. Development of Agent-Driven Systems: from i* Architectural Models to Intentional Agents Code. -

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15