How Oral History Can Contribute To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2013 Newsletter 2

Newsletter 2 December 2013 In ThisIN THISIssue: ISSUE Dates to Note 2 DWS News 3 Holiday Fair Photos 4 Holiday Fair Help Needed 5 Basketball Champs 6 Colorado Gives Day Results 7 DWS Spartans Middle School A Team Carolyn’s College Corner 10 Crowns Undefeated Season with Anthroposophy Notes 11 Parent Education 13 League Championship Title! Community Notes 14 1 UPCOMING DATES TO NOTE Dec. 20 Jan. 8, 9 am Shepherd’s Play at 9:30 & 11 am Epiphany Assembly Evening performance at 7pm Early Dismissal: 12 Noon for all Jan. 10, 6-8 pm students Parent Council Baked Potato Night NO AFTERCARE Jan. 11, 6-8 pm Dec. 21—Jan.5: Winter Break Family Friendly Improv Night Back to School on Monday, Jan. 6 No Winter Break Camp Available Jan. 13, 5:30 pm Wisdom of Waldorf Evening Dec. 28, 10:30-1:00 Mercury Group (Anthroposophical Youth Jan. 14, 7-9 pm Group) Art Project & Potluck with Turbo Teens Marielle Levin Parent Evening with Douglas Gerwin “Sometimes our fate resembles a fruit tree in winter. Who would think that those branches would turn green again and blossom? But we hope it, we know it.” —Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 2 TWO DWS STUDENTS SELECTED FOR ALL-STATE ORCHESTRA Sophomore Marley Aiu (cellist) and Junior Rachel Prendergast (violinist) have been accepted into the Colorado All-State Orchestra. Both girls sent in their applications and recorded auditions in November, along with hundreds of other high school music students from all over Colorado. Results were announced last Friday: not only were both Rachel and Marley accepted, but both were placed in the Symphony orchestra, which is the more advanced of the two All-State orchestras. -

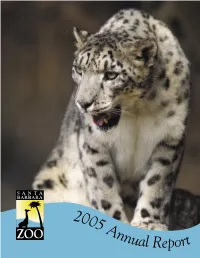

5 Ann Ual Report

�� ��� ���� ����������� FROM THE executiveFROMFROM TTHEHE notes ZOO DIRECTOR BOARD PRESIDENT 2005 provided a brief respite from all the construction In 2005 the Santa Barbara Zoo continued to reach out activity of 2004. It was a year devoted to preparing the to all segments of our community. The enthusiasm of fi nal documentation of the master plan for submission to our professional staff continues to improve the facility Santa Barbara’s City Planning Department. The review of and programs for all to enjoy. In addition, these talented the Zoo’s master plan and the preparation of the sections professionals hold leadership positions in national and of the plan began in 2003 after the Planning Department international conservation, research, and zoological changed the review process in order to comply with the organizations. California Environmental Quality Act - CEQA. This is the most comprehensive set of documents ever prepared in In April we received a new fi ve-year accreditation from the Zoo’s 42 years of operation. the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). The AZA sets the bar at a top level for its members, and we are one The Zoo has now completed its documentation of site of only 210 zoos and aquariums in the nation that qualify archaeology, hydrology (primarily run-off ), parking and for this honor. Our executive leaders expect very high traffi c, accessibility (compliance with the Americans with standards, and the entire Zoo staff is to be commended for Disabilities Act - ADA), biology, and the preliminary plans working tirelessly to achieve this goal. It’s not just the staff for the next phase of capital projects. -

This Land Sings: Inspired by the Life and Times of Woody Guthrie

This Land Sings: Inspired by the Life and Times of Woody Guthrie Saturday, October 24, 2020 7:30 PM Livestreamed from Universal Preservation Hall David Alan Miller, conductor Kara Dugan, mezzo soprano Michael Maliakel, baritone F. Murray Abraham, narrator Welcome to the Albany Symphony’s 2020-21 Season Re-Imagined! The one thing I have missed more than anything else during the past few months has been spending time with you and our brilliant Albany Symphony musicians, discovering, exploring, and celebrating great musical works together. Our musicians and I are thrilled to be back at work, bringing you established masterpieces and gorgeous new works in the comfort and convenience of your own home. Originally conceived to showcase triumph over adversity, inspired by the example of Beethoven and his big birthday in December, our season’s programming continues to shine a light on the ways musical visionaries create great art through every season of life. We hope that each program uplifts and inspires you, and brings you some respite from the day-to-day worries of this uncertain world. It is always an honor to stand before you with our extraordinarily gifted musicians, even if we are now doing it virtually. Thank you so much for being with us; we have a glorious season of life- affirming, deeply moving music ahead. David Alan Miller Heinrich Medicus Music Director This Land Sings: Inspired by the Life and Times of Woody Guthrie Saturday, October 24, 2020 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed from Universal Preservation Hall David Alan Miller, conductor Kara Dugan, mezzo soprano Michael Maliakel, baritone F. -

NEIL KREPELA ASC Visual Effects Supervisor

NEIL KREPELA ASC Visual Effects Supervisor www.neilkrepela.net FILM DIRECTOR STUDIO & PRODUCERS “THE FIRST COUPLE” NEIL KREPELA BERLINER FILM COMPANIE (Development – Animated Feature) Mike Fraser, Rainer Soehnlein “CITY OF EMBER” GIL KENAN FOX/WALDEN MEDIA Visual Effects Consultant Gary Goetzman, Steven Shareshian “TORTOISE AND THE HIPPO” JOHN DYKSTRA WALDEN MEDIA Visual Effects Consultant “TERMINATOR 3: RISE OF THE JONATHAN MOSTOW WARNER BROTHERS MACHINES” Joel B. Michaels, Gale Anne Hurd, VFX Aerial Unit Director Colin Wilson & Cameraman “SCOOBY DOO” RAJA GOSNELL WARNER BROTHERS Additional Visual Effects Supervision Charles Roven, Richard Suckle “DINOSAUR” ERIC LEIGHTON WALT DISNEY PICTURES RALPH ZONDAG Pam Marsden “MULTIPLICITY” HAROLD RAMIS COLUMBIA PICTURES Visual Effects Consult Trevor Albert Pre-production “HEAT” MICHAEL MANN WARNER BROTHERS/FORWARD PASS Michael Mann, Art Linson “OUTBREAK” WOLFGANG PETERSEN WARNER BROTHERS (Boss Film Studio) Wolfgang Petersen, Gail Katz, Arnold Kopelson “THE FANTASTICKS” MICHAEL RITCHIE UNITED ARTISTS Linne Radmin, Michael Ritchie “THE SPECIALIST” LUIS LLOSA WARNER BROTHERS Jerry Weintraub “THE SCOUT” MICHAEL RITCHIE TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (Boss Film Studio) Andre E. Morgan, Albert S. Ruddy “TRUE LIES” JAMES CAMERON TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (Boss Film Studio) James Cameron, Stephanie Austin “LAST ACTION HERO” BARRY SONNENFELD COLUMBIA PICTURES (Boss Film Studio) John McTiernan, Steve Roth “CLIFFHANGER” RENNY HARLIN TRISTAR PICTURES Academy Award Nominee Renny Harlin, Alan Marshall “BATMAN RETURNS” -

ASIC Unclaimed Money Gazette

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. UM1/16, Monday 29 February 2016 Published by ASIC ASIC Gazette Contents Unclaimed consideration for compulsory acquisition - S668A Corporations Act RIGHTS OF REVIEW Persons affected by certain decisions made by ASIC under the Corporations Act 2001 and the other legislation administered by ASIC may have rights of review. ASIC has published Regulatory Guide 57 Notification of rights of review (RG57) and Information Sheet ASIC decisions – your rights (INFO 9) to assist you to determine whether you have a right of review. You can obtain a copy of these documents from the ASIC Digest, the ASIC website at www.asic.gov.au or from the Administrative Law Co-ordinator in the ASIC office with which you have been dealing. ISSN 1445-6060 (Online version) Available from www.asic.gov.au ISSN 1445-6079 (CD-ROM version) Email [email protected] © Commonwealth of Australia, 2016 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate this work should be made to: Gazette Publisher, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, GPO Box 9827, Melbourne Vic 3001 ASIC GAZETTE Commonwealth of Australia Gazette UM1/16, Monday 29 February 2016 Unclaimed consideration for compulsory acquisition Page 1 of 270 Unclaimed Consideration for Compulsory Acquisition - S668A Corporations Act Copies of records of unclaimed consideration in respect of securities, of the following companies, that have been compulsorily -

F12a-7-2003.Pdf

.... STATE OF CALIFORNIA- THE RESOURCES AGENCY GRAY DAVIS, Governor CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION :., 45 FREMONT STREET, SUITE 2000 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105-2219 VOICE AND TDD (415) 904-5200 ·' r·..,-·.._ ~.I' ~,.~ \.} ',:.: i 1 ~ F 12a Briefing Memo Date: June 16, 2003 To: Commissioners and Interested Persons From: Peter Douglas, Executive Director Elizabeth A. Fuchs, Manager, Statewide Planning and Federal Consistency Division Mark Delaplaine, Federal Consistency Supervisor Subject: Naval Postgraduate School Active Acoustics and Potential Effects on Sea Otters Background In response to public comments at the May 2003 Coastal Commission meeting (Attachment 5), the Commission requested its staff to determine what, if any, active offshore underwater acoustic activities were being conducted by the Naval Postgraduate School (NPGS) in Monterey. Allegations were made at the meeting that such acoustics could be affecting sea otters. The Commission also requested the staff to look into whether the activities should be reviewed under the federal agency provisions of the Coastal Zone Management Act (as have Scripps ATOC 1 sound experiments and Navy LFA sonar). Navy Sound Sources The Navy conducts two types of activities at the NPGS involving active underwater acoustics: underwater autonomous vehicles (UAVs) and RAFOS3 floats. Both ofthese types of equipment are used to study underwater currents and other subsea phenomena, and both are types of equipment used by other oceanographic institutions around the U.S. that are generally not, to date, subject to regulatory controls. I Acoustic Thermometry of Ocean Climate (ATOC) (CC-II 0-94 & CDP 3-95-40). 2 Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System Low-Frequency Active (SURTASS LF A) Sonar Program (CD-I13-00). -

The Inventory of the Michael Douglas Collection #1839

The Inventory of the Michael Douglas Collection #1839 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Douglas, Michael #1839 3/31/16, 4/7/16 Preliminary Listing I. Wardrobe. A. Costumes. Box 1-2 1. “The American President.” Box 3-8 2. “Behind the Candelabra.” Box 9 3. “Disclosure.” 4. “A Perfect Murder.” 5. “Romancing The Stone.” Box 9-14 6. “The Game.” Box 15-20 7. “The In-Laws.” Box 21-25 8. “It Runs In The Family.” Box 26 9. “Jewel Of The Nile.” Box 27-32 10. “Traffic.” Box 33-37 11. “Wonder Boys.” Box 38 12. “Wall Street.” B. Hanging Costumes. Pkg. 1-2 1. “The American President.” Pkg. 3-35 2. “Behind the Candelabra.” Pkg. 36-57 3. “The Game.” Pkg. 58-78 4. “The In-Laws.” Pkg. 79-116 5. “It Runs In The Family.” Pkg. 117 6. “Wall Street.” Box 39-56 C. Personal. Pkg. 118-124 D. Hanging Personal. II. Printed Materials. A. Files. Box 57-88 1. Clippings (not on their spreadsheets). Box 88 2. General. B. Blueprints/Maps. C. Internet printouts. D. Postcards. Box 89-91 E. Magazines. Box 92-94 F. Programs. Box 95 G. Newspapers. Box 95-96 H. Reviews. Box 96 I. Clippings. J. Booklets. K. Pamphlets. L. Fliers. Box 97 M. Posters. Pkg. 125-141 N. Oversized posters. Douglas, Michael (3/31/16, 4/7/16) Page 1 of 46 III. Film and Video. Box 98-131 A. VHS. Box 131 B. 8 mm cassettes. C. Mini-DVs. Box 132 D. DV-Cams. Box 133 E. DVDs. Box 134 F. -

TONY ADLER 1St ASSISTANT DIRECTOR DGA

TONY ADLER 1st ASSISTANT DIRECTOR DGA FEATURES THE TRAP One Unit/Sony Prod: Yanely Ardy, Shakim Compere Dir: Eric White IT’S TIME It’s Time LLC Prod: Wendy Yamano, Kelly Tenney Dir: Frank Waldek DEUCES One Unit/Sony Prod: Shakim Compere, Otis Best Dir: Jamal Hill UNFINISHED BUSINESS (LA Unit) Regency/Fox Prod: Todd Black, Jason Blumenthal Dir: Ken Scott LOVE IS ALL YOU NEED? Genius Films Prod: Giovanni Corvino, Michael Zampino Dir: Rocco Shields AMERICAN BEAUTY DreamWorks Prod: Bruce Cohen, Dan Jinks Dir: Sam Mende THE SALTON SEA Castle Rock Prod: Jim Behnke, Frank Darabont Dir: DJ Caruso JONAH HEX (LA Unit) Legendary Ent./Warner Bros. Prod: William Fay, Akiva Goldsman Dir: Jimmy Hayward BOBBY Z (Mexico) NU Image Prod: Keith Samples, Heidi Jo Markel Dir: John Herzfeld THE EXORCISM OF EMILY ROSE Lakeshore Prod: Andre Lamal, Terry McKay Dir: Scott Derrickson (U.S. Unit) THE BIG EMPTY (Assoc. Producer) Echo Lake Prod: Steve Bickel, Jeffrey Kramer Dir: Steve Anderson AMANDA Cinergi Pictures Prod: Donna Dubrow, John McTiernan Dir: Bobby Roth THREE DAYS IN VEGAS (Co-Producer) Paradise/MGN Prod: Armen Ananikyan, Armen Grigoryan Dir: Gor Kirakosian IN TIME Fox/Regency Prod: Bob Harper, Amy Israel Dir: David Leitch LOST AND FOUND IN ARMENIA Independent Prod: Maral Djerejian, Hasmik Hakobyan Dir: Gor Kirakosian CON MAN (Co-Producer) Universal/Insomnia Prod: Nick Arthur, Scott Atkins Dir: Bruce Caulk WHIP IT (2nd Unit) Fox Searchlight Prod: Peter Douglas, Joseph Drake Dir: Drew Barrymore THE DEAD GIRL Lakeshore Prod: Terry McKay, David Rubin Dir: Karen Moncrieff DAREDEVIL (LA Unit) 20th Century Fox Prod: Avi Arad, Bernard Williams Dir: Mark Johnson THE GRAY MAN (Prod. -

2013 Annual Report

2013 ANNUAL REPORT RONALD A MUNOZ WEHISMAN MUNOZ ANTONIO MUNOZ DIAZ GREGORY B MUNRO JOHN MUNRO BRETT A MUNSEY COURTNEY L MUNSEY GLORIA MUNSON W ANDREWS MUNSON JR DANIEL MUNZO RAJADURAI MURALITHARAN PATRICK MURAWSKI PAUL MURCHEK KENNETH MURDOCH DONNY R MURDOCK VICTOR J MURILLO GUY MURIN JUSTIN M MURPHREE BILLY L MURPHY BRANDON MURPHY BRIAN MURPHY CHRISTOPHER MURPHY DALE MURPHY DAN MURPHY DARREN GEORGE MURPHY DAVID MURPHY DAVID MURPHY GERARD E MURPHY JACKIE MURPHY JEANETTE MURPHY KENNETH MURPHY MARTIN MURPHY MATTHEW MURPHY MCCONNELL L MURPHY MICHAEL MURPHY MICHAEL DEWAYNE MURPHY PHILIP MURPHY RODNEY MURPHY SARA J MURPHY SCOTT A MURPHY SEAN MURPHY SEAN K MURPHY SHARON A MURPHY STEPHEN L MURPHY STEVEN C MURPHY WILLIAM M MURPHY CATHERINE MURRAY DANIEL G MURRAY JEFFREY MURRAY JUDITH A MURRAY KIMONICA B MURRAY LAWRENCE MURRAY NATHAN M MURRAY PAUL MURRAY RICHARD MURRAY TODD F MURRAY WILLIAM A MURRAY JR WILLIAM L MURRAY JR MANIKANDAN MURSUGASAN SASIKUMAR MURUGAIYAN DALE MURZYN ANDERSON MUSE JEFF MUSE JEFFREY MUSE SAMUEL MUSE III TODD MUSE STEPHEN A MUSGRAVE JOHN L MUSGRAVES LARRY MUSHING BARRY D MUSICK DUSTIN MUSSA TROY MUSSELMAN RICHARD D MUSSER JEFFREY MUSSON WAZEEM MUSTAPHA SONG HENG MUTH RENGARAJ MUTHAIAH ALEX J MUTSCHELKNAUS BENJAMIN R MUTSCHELKNAUS AARON J MUTSCHLER PAUL MUZIO KARYN STEPHANZ MUZZEY BOBBY R MYERS BRENDA MYERS CATHY KAY MYERS COREY MYERS DARREN J MYERS DARRYL MYERS DAVID C MYERS ERIC MYERS GLEN MYERS GLEN L MYERS HEATH A MYERS JEFFERY MYERS JESSICA R MYERS JIMMY DALE MYERS KRISTIE MYERS MICHAEL MYERS NOAH A MYERS PATRICK MYERS -

Colby Alumnus Vol. 74, No. 3: May 1985

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1985 Colby Alumnus Vol. 74, No. 3: May 1985 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 74, No. 3: May 1985" (1985). Colby Alumnus. 126. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/126 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. COLBY'S LEADERSHIP President Overseers Alumni Council Executive Committee William R. Cotter Richard L. Abedon '56 David M. Marson '48, chair Harold Alfond Jerome F. Goldberg '60, vice chair Frank 0. Apantaku '71 John R. Cornell '65 Trustees Leigh B. Bangs '58 Susan Comeau '63 Charles P. Barnes I I '54 R. Dennis Dionne '61 J. Robert Alpert '54 Clifford A. Bean '51 Laurie B. Fitts '75 Robert N. Anthony '38 Patricia Downs Berger '52 Susan Smith Huebsch '54 Anne Lawrence Bondy '46 William L. Bryan '48 Germaine Michaud Orloff '55 H. Ridgely Bullock '55 Ralph J. Bunche, Jr. '65 Robert W. Burke '61 Christine M. Celata '70 Alida Millik<!n Camp, L.H.D. '79 James R. Cochrane '40 Parents Association Levin H. Campbell, LL.D. '82 Edward R. Cony '44 Clark H. Carter '40 Richard and Susan Armstrong, co-chairs H. King Cummings John Gilray Christy James and Carlene Webster, vice co-chairs Augustine A. D' Amico '28 John S. Dulaney '56 Edith E. -

James Horner

JAMES HORNER AWARDS / NOMINATIONS GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (20 10 ) AVATAR Best Score Soundtrack Album GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (20 10 ) “I See You” from AVATAR Best Song Written for a Motion Picture or Televi sion * WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD “I See You” from AVATAR NOMINATION (2010) Best Original Song* WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD AVATAR NOMINATION (2010) Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2009) AVATAR Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2009) AVATAR Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2009) AVATAR Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2009) “I See You” from AVATAR Best Original Song* ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2003) HOUSE OF SAND AND FOG Best Original S core GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2002) A BEAUTIFUL MIND Best Score Soundtrack Album ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2001) A BEAUTIFUL MIND Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2002) A BEAUTIFUL MIND Best Original Score GOLDEN SATELLITE AWARD (2002) “All Love Can Be” from A BEAUTIFUL MIND Best Original Song * GRAMMY AWARD (1998) “My Heart Will Go On” from TITANIC Song of the Year * 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 JAMES HORNER GRAMMY AWARD (1998) “My Heart Will Go On” from TITANIC Record of the Year * GR AMMY AWARD (1998) “My Heart Will Go On” from TITANIC Best Song Written for a Motion Picture or Television * AMERICAN MUSIC AWARD (1998) TITANIC Favorite Soundtrack Album BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (199 7) TITANIC Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD (1997) TITANIC Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD (1997) “My Heart Will Go On” from TITANIC Best Original -

Full Book PDF Download

TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page i The naval war film TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page ii TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page iii The naval war film GENRE, HISTORY, NATIONAL CINEMA Jonathan Rayner Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page iv Copyright © Jonathan Rayner 2007 The right of Jonathan Rayner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7098 8 hardback EAN 978 0 7190 7098 3 First published 2007 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in 10.5/12.5pt Sabon by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page v For Sarah, who after fourteen years knows a pagoda mast when she sees one, and for Jake and Sam, who have Hearts of Oak but haven’t got to grips with Spanish Ladies.