A Study of Child Trafficking in the Kosi Region of Bihar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIHAR STATE POWER TRANSMISSION COMPANY LIMITED (Reg

BIHAR STATE POWER TRANSMISSION COMPANY LIMITED (Reg. Office: 4th Floor, Vidyut Bhawan, Bailey Road, Patna-800021) (CIN- U40102BR2012SGC018889) (Department of Power Management Cell) BSPTCL has revised the Business Plan, the copy of the same is attached herewith for ready reference also the revised para-wise in respect of earlier reply vide letter no.- 379 dated – 20/12/2018 regarding Business Plan (BP) for FY 2019-20 to FY 2021-22 submitted to Hon’ble BERC vide Letter No.- 330 dated – 02.11.2018 1. (a) The mentioned are indicated as below with units: S. No. of 3.5.1 of BP Units of Amount 11 to 13 In Crore 29 to 31 In Crore 32 In Rupees 39 In Crore 53 to 60 In Rupees 70 to 74 In Crore 75 to 77 In Rupees 78 to 80 In Crore (b) At Sl. No.- 7 & 22 of 3.6 of Business plan claimed twice which may treated as same and Sl. No.- 22 may be deleted. (c) Also at Sl. No.- 65 & 66 of 3.5.1 of Business plan : It is not a type of repetition, these are of two different transmission lines: S.No. Name of Element (Transmission line, Commissioning COST(Rs.) Scheme Substation, Bay Extension, etc.) Date/LDOC) Procurement and Construction of 33KV line bays in form of Indoor VCB panels at 14 65 30.11.2018 33.02 Crore ADB nos. of AIS Sub-station under Transmission Circle Gaya Procurement and Construction of 33KV line bays in form of Indoor VCB panels at 14 66 30.11.2018 40.25 Crore ADB nos. -

Total Post - 03 ( Sc Male)

TOTAL POST - 03 ( SC MALE) QUALIFICATION % FATHER'S CANDIDATE /HUSBAND'S DATE OF BIRTH ADDRESS S S N NAME TET POINT % GENDER NAME % APP.NO. TET TYPE REMARKS TRAINING NAME OF G % G CATEGORY INTER INSTITUTION PERCENTAGE TET WEITAGE MERITMARKS TOTAL MERIT RESERVATION RESERVATION MATRIC PASSINGYEAR TRAININ TRAINING TYPE 12 3 4 5 6 78 9101112131415161718 19 20 KASHIBARI ANIL KUMAR SAHDEO 1 121 04/01/1987 HAT SC 77.60 64.80 79.42 73.94 72.66 4 77.94 NIOS CTET 2019 DAS KUMAR DAS MALE KISHANGANJ D.EL.ED S L BARSOI MITHUN MANOJ KUMAR S M B C 49 2 48 25/06/1989 MAJUMDAR SC 63.42 55.33 75.76 64.84 60.67 2 66.84 B.ED CTET 2019 KUMAR DAS DAS MALE KATIHAR DOU PARA BARSOI BLE YOGENDRA RAGHUNATHP KAMLES S R K P 3 16 PRASAD RAVI 13/12/1988 UR BARSOI SC 54.85 57.00 77.00 62.95 56.00 2 64.95 B.ED CTET 2019 KUMAR DAS MALE COLLEGE BAH DAS KATIHAR RAGHUNATHP KUMAR KISHOR KUMAR D S COLLEGE 4 15 07/01/1991 UR BARSOI SC 63.20 53.00 71.84 62.68 62.00 2 64.68 B.ED CTET 2019 PRASHANT DAS MALE KATIHAR KATIHAR NATIONAL ASHOK TEACHERS BALRAMPUR 5 57 KUMAR JOGEN MODAK 05/04/1991 SC 46.40 67.20 74.38 62.66 62.67 2 64.66 TRAINING B.ED CTET 2019 KATIAHR MALE MODAK COLLEGE PATNA YOGENDRA RAGHUNATHP SANTOSH 6 111 PRASAD RAVI 28/06/1985 UR BARSOI SC 58.14 49.55 76.00 61.23 50.66 2 63.23 NIOS CTET 2019 KUMAR DAS MALE DAS KATIHAR D.EL.ED QUALIFICATION % FATHER'S CANDIDATE /HUSBAND'S DATE OF BIRTH ADDRESS S S N NAME TET POINT % GENDER NAME % APP.NO. -

Si No. District Block Panchayat Village Popln

LIST OF URC ALLOTTED TO BANKS FOR OPENING OF BANKING OUTLETS BY 31.12.2017 SI NO. DISTRICT BLOCK PANCHAYAT VILLAGE POPLN. ALLOTTED TO 1 ARARIA FORBESGANJ AURAHI EAST Hardia 9260 ALLAHABAD BANK 2 ARWAL KAPRI KOCHAHASA PANCHAYAT Kochahsa 6409 ALLAHABAD BANK 3 BEGUSARAI BACHHWARA RANI-I Gopalpur 5094 ALLAHABAD BANK 4 BEGUSARAI BIRPUR NOULA Gopalpur 5094 ALLAHABAD BANK 5 BEGUSARAI BEGUSARAI CHILMIL Hardia 7185 ALLAHABAD BANK 6 BHOJPUR PIRO TAR Tar 6123 ALLAHABAD BANK 7 KATIHAR BARARI RAUNIA Rounia 9273 ALLAHABAD BANK 8 MADHUBANI LAUKAHA (KHUTAUNA) MAJHAURA Pathrahi 8365 ALLAHABAD BANK 9 MADHUBANI MADHUBANI KHAJURI Khajuri 5152 ALLAHABAD BANK 10 PATNA PALIGANJ MADHAMA MAKHMILPUR Makhmilpur 6392 ALLAHABAD BANK 11 SAHARSA SONBARSA ATALKHA Jamhra 9421 ALLAHABAD BANK 12 SHEIKHPURA Sheikhpura Kosra Kosra 6707 ALLAHABAD BANK 13 ARARIA BHARGAMA VISHAHARIYA Bisaria 9628 ALLAHABAD BANK 14 ARARIA FORBESGANJ MUSAHARI Musahari 5399 ALLAHABAD BANK 15 ARARIA NARPATGANJ KHABDAH Kandhaili 5012 ALLAHABAD BANK 16 ARARIA RANIGANJ DHAMA Dhama 6142 ALLAHABAD BANK 17 ARARIA SIKTY KAUAKOH Pothia 7723 ALLAHABAD BANK 18 NALANDA HILSA AKABARPUR Akbarpur 5305 ALLAHABAD BANK 19 NALANDA PARBALPUR SHIVNAGAR Bazidpur Khirauti 6533 ALLAHABAD BANK 20 NALANDA SILAO GORAWAN Gorawan 6282 ALLAHABAD BANK 21 VAISHALI BHAGWANPUR KARHARI Karhari 5424 ALLAHABAD BANK 22 VAISHALI CHEHRAKALA RASULPUR FATAH Rasulpur Fateh 5231 ALLAHABAD BANK 23 VAISHALI MAHUA FATAHPUR PAKRI Fatehpur Pakri 5778 ALLAHABAD BANK 24 VAISHALI RAJAPAKAR LAGURAO VILNUPUR Nagrawan 5160 ALLAHABAD BANK 25 MADHEPURA -

![Z] Ftyk F'k{Kk ,Oa Izf'k{Kk Lal Fkku ¼Mk;V½ Fd'kuxat](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8079/z-ftyk-fk-kk-oa-izfk-kk-lal-fkku-%C2%BCmk-v%C2%BD-fdkuxat-3718079.webp)

Z] Ftyk F'k{Kk ,Oa Izf'k{Kk Lal Fkku ¼Mk;V½ Fd'kuxat

dk;kZy; %& izkpk;Z] ftyk f'k{kk ,oa izf'k{k.k laLFkku ¼Mk;V½ fd'kuxat Mh0,y0,M0 l= 2019&21 esa ukekadu gsrq dyk ,oa okf.kT; fo"k; ds vH;fFkZ;ksa dh izFke vkSicaf/kd p;fur es/kk lwph Roster Male/ Police Qualific Merit Categ Remar Sl No Reg. Id Candidate Name Father's Name Village Post District DOB Mobile No. Point Female Station ation Marks ory ks 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12131415 16 DIETKN2019 AT Intermedi UR/ GEN MD AHRAR ALAM Male MD AKHLAQUE JOKIHAT JOKIHAT Araria 05-08-01 88.3 EBC 9693464792 URDU 1 051414578 SISOUNA ate DIETKN2019 AJAY KUMAR RAGHUNANDAN MUKHIYA Intermedi EBC Male KODHAILI PALASI PALASI Araria 05-04-00 78.9 EBC 7061181726 2 04309605 BISHWAS BISHWAS ate UR-F/ DIETKN2019 SHYAM NARAYAN Kishanga Intermedi 3 ANISHA KUMARI Female BIBIGANJ BIBIGANJ BIBIGANJ 07-01-02 77.4 SC 9771626045 GEN 051012464 DAS nj ate DIETKN2019 SHEKHAR KUMAR AT BASAK BAHADUR BAHADURG Kishanga Intermedi SC Male RAJ KUMAR BASAK 06-06-99 77.7 SC 9693208900 4 051515359 BASAK TOLA GANJ ANJ nj ate DIETKN2019 DEEPAK KUMAR AT-BAHADUR DHANPAT KOCHADHA Kishanga Intermedi UR/ GEN Male HIRA LAL THAKUR 03-05-02 89.7 EBC 8969982899 5 051213119 THAKUR PURANI GANJ MAN nj ate DIETKN2019 GAUTAM KUMAR KHIKIRTOHAT BAGALBA KOCHADHA Kishanga Intermedi BC Male AMAR LAL SINGH 04-04-01 78.6 BC 9801116837 6 050912042 SINGH LA RI MAN nj ate DIETKN2019 BAGNAGA MAHALGA Intermedi Gen(E UR/ EWS MD AFTAB ALAM Male ABDURRAHMAN masuriya Araria 04-06-89 71.375 7091183057 7 050911821 R ON ate WS) DIETKN2019 AT MACHHA Intermedi EBC-F BIBI NIKHAT ARA Female AKHTER HUSSAIN AMOUR Purnea -

Detailed Report PHC TO

May-2018 PHC TO CHC (30 BEDDED) (Under MSDP) SL A.A. Amount Amount Received Expenditure Till Total no. Completed Name of work Ongoing Projects Not Started Projects REMARKS NO (in Rs. Lakh) (in Rs. Lakh) Date (in Rs Lakh) of Projects Projects 11776.25 1 Construction of PHC to CHC (Minority) 0.00 2677.38 25 6 7 12 (471.05 per unit) Detailed Report AGREEMEN UP TO DATE SL ADMINISTRATIVE APPROVAL DETAIL NAME OF DATE OF DATE OF PHYSICAL NAME OF NAME OF DISTRICT NAME OF WORK T AMOUNT PAYMENT REMARKS NO CONTRACTOR START COMPLETION Dy.G.M G.M Amount (in rs lakh) Date (RS in lakh) STAGE % (RS in lakh) CHC AT DIGHALBANK, Sri Pankaj Sri Sanjeev 1 KISHANGANJ 471.05 13-Apr-15 Shafique Alam 385.56 28-Apr-16 27-Apr-17 Completed 100% 273.54 KISHANGANJ Kumar Ranjan CHC AT THAKURGANJ, Sri Pankaj Sri Sanjeev Letter sent to 2 KISHANGANJ 471.05 13-Apr-15 Shafique Alam 386.25 28-Apr-16 27-Apr-17 Not Started 0.00 KISHANGANJ Kumar Ranjan D.M for land CHC AT BAHADURGANJ, Sri Pankaj Sri Sanjeev 3 KISHANGANJ 471.05 13-Apr-15 Shafique Alam 381.55 28-Apr-16 27-Apr-17 Completed 100% 266.56 KISHANGANJ Kumar Ranjan CHC AT KOCHADHAMAN, Sri Pankaj Sri Sanjeev 4 KISHANGANJ 471.05 13-Apr-15 Shafique Alam 384.91 28-Apr-16 27-Apr-17 Completed 100% 193.43 KISHANGANJ Kumar Ranjan Sri Pankaj Sri Sanjeev 5 ARARIYA CHC AT PALASI, ARARIYA 471.05 13-Apr-15 Topline Infra 389.75 28-Apr-16 27-Apr-17 Completed 100% 231.67 Kumar Ranjan CHC AT AZAMNAGAR, Sri Pankaj Sri Sanjeev 6 KATIHAR 471.05 13-Apr-15 Pankaj Kumar Singh 387.17 29-Apr-16 28-Apr-17 Completed 100% 312.09 Handed Over KATIHAR -

Sl.No Name and Address of Centre Name of District Name of the Counsellor Contact No Name of Medical Incharge/ ICTC Manager Contact No

Sl.No Name and address of Centre Name of District Name of the counsellor Contact No Name of Medical Incharge/ ICTC Manager Contact No Araria Ahmad Nadim Ahsan 9709576800 Dr. D.D.Singh, 9470003030, 1 SH, Araria District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854311 Dr. D.D.Singh, 9470003030, Araria 2 PPTCT, SH, Araria District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854311 Deepika Singh Sehgal 9430265287 Araria 3 Ref. Hos. Farbisganj District‐Araria, Pin Code‐ 854318 Umakant Sharma 9234269575, 9234532201 M.O‐Jay Narayan Prasad ,9470003033, Araria 4 Ref. Hos. Raniganj District‐Araria, Pin Code‐ 854334 Nagendra Prasad 9507788338 Dr. Abdhesh Kumar 9470003034, Araria 5 PHC Jokihaat District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854329 Pankaj Kumar 9771103971 M.D‐Siftain alam, Araria 6 PHC Kursakanta District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854331 Vacant Dr. Rajendra Kumar, Araria 7 PHC Narpatganj District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854335 NA NA Dr. Yogendra Pd. Singh, 9955275569 Araria 8 PHC Palasi District‐Araria, Pin Code‐854333 Amit Kumar 9470844168 Dr. Jahagir Alam 9470003037 Araria 9 PHC Sikati , Pin Code‐854333 Vacant ‐9430806886 Arwal NA NA Dr.Bindeshwari Sharma 9430059427 Centre Phone ‐ 06337‐229276, 10 Sadar Hospital, District‐ Arwal, Pin Code‐804401 Dr.Bindeshwari Sharma 9430059427 Centre Phone ‐ 06337‐229276, Arwal 11 PPTCT, Sadar Hospital, District‐ Arwal, Pin Code‐804401 Kavita Sinha 9576087610 Aurangabad Rakesh Kumar. Rai 9431429761 Dr. S.K. Aman, 9470003061 12 Sadar Hosp. Aurangabad District‐Aurangabad, Pin Code‐824102 PPTCT, Sadar Hosp. Aurangabad District‐Aurangabad, Pin Code‐ Aurangabad Anjani Kumari Dr. S.K. Aman, 9470003061, 13 824102 Banka Binod Kumar Yadav 9430611053 Dr. N.K.Vidyerthi 9470003073, 14 Sadar Hospital Banka District‐ Banka, Pin Code‐813102 Banka 15 PPTCT, Sadar Hospital Banka District‐ Banka, Pin Code‐813102 Dolly Kumari 9430966599 NA Sadar Hospital District‐Begusarai, Pin Code‐851101 Begusarai Santosh Kumar Sant 9430066712 A.K. -

Art & Commerce Final Pdf.Xlsx

D.El.Ed. 2020-22 Art Commerce DIET KNE ftyk f'k{kk ,oa izf'k{k.k laLFkku]¼Mk;V½ fd'kuxat Mh0,y0,M0 l= 2020&22 esa ukekadu gsrq izkIr vkosnuksa dk vkifÙk fujkdj.k ds mijkUr [email protected]; ladk; dk vkSicaf/kd es/kk lwphA SBI Matric Tenth Twelve Candidate Name in Handic Type of Categor Are You Permanent Permanent Permanent Collect +Enter Sr No. Reg. Id Father's Name Mother's Name Gender DOB Mobile No. Email Id Permanent Village Percen Percen English apped Disable y Urdu Post Office Police Station District Referenc Percen t t e No. t Averag DIETKN2021 DEEPAK KUMAR deepakkumar1841 PURANI HAT DHANPATGA KOCHADHAM Kishangan DUE059 1 HIRA LAL THAKUR ASHA DEVI Male 03-05-02 8969982899 No EBC No 93.1 86.4 89.75 010325793 THAKUR [email protected] BARBATTA NJ AN j 0941 DIETKN2020 BRAJ BHUSHAN komalkashishpop1 MILAN Kishangan DUE035 2 KOMAL KUMARI SEEMA DEVI Female 05-04-98 7827996510 No EBC No KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ 89.3 88.35 88.83 123122849 PRASAD [email protected] PALLY,KISHANGANJ j 2153 DIETKN2021 sanakauser1919@ AT- TEGHARIA, KOCHADHAM Kishangan DUE056 3 SANA KAUSER KAUSER BABUL SHABANA HASMI Female 01-01-00 6203201683 No BC No KANHIYABARI 87.39 87.4 87.4 010324922 gmail.com KISHANGANJ AN j 2337 DIETKN2021 CHANDRAKANT srbhkumar26@gm RADHANAGA DUE056 4 SAURABH KUMAR LALITA DEVI Male 10-01-96 7827228884 No BC No GADDI RAGHOPUR Supaul 89.3 84 86.65 010325039 SWARNAKAR ail.com R 7187 DIETKN2021 MD HASNAIN SAHELA KAUSAR saquibhasnain987 KHARIBASTI BHAWANIGA Kishangan DUE061 5 MD SAQUIB HASNAIN Male 05-03-98 7033178966 No BC No THAKURGANJ 98 74.8 86.4 010426289 ALAM -

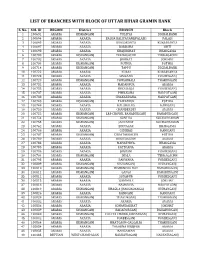

List of Branches with Block of Uttar Bihar Gramin Bank

LIST OF BRANCHES WITH BLOCK OF UTTAR BIHAR GRAMIN BANK S. No. SOL ID REGION District BRANCH Block 1 100691 ARARIA KISHANGANJ TULSIYA DIGHALBANK 2 100694 ARARIA ARARIA BALUA KALIYAGANJ(PALASI) PALASI 3 100695 ARARIA ARARIA KURSAKANTA KURSAKANTA 4 100697 ARARIA ARARIA BARDAHA SIKTI 5 100698 ARARIA ARARIA KHAJURIHAT BHARGAMA 6 100700 ARARIA KISHANGANJ TERHAGACHH TERRAGACHH 7 100702 ARARIA ARARIA JOKIHAT JOKIHAT 8 100704 ARARIA KISHANGANJ POTHIA POTHIA 9 100714 ARARIA KISHANGANJ TAPPU DIGHALBANK 10 100722 ARARIA ARARIA KUARI KURSAKANTA 11 100723 ARARIA ARARIA SIMRAHA FORBESGANJ 12 100729 ARARIA KISHANGANJ POWAKHALI THAKURGANJ 13 100732 ARARIA ARARIA MADANPUR ARARIA 14 100733 ARARIA ARARIA DHOLBAJJA FORBESGANJ 15 100737 ARARIA ARARIA PHULKAHA NARPATGANJ 16 100738 ARARIA ARARIA CHAKARDAHA. NARPATGANJ 17 100748 ARARIA KISHANGANJ TAIYABPUR POTHIA 18 100749 ARARIA ARARIA KALABALUA RANIGANJ 19 100750 ARARIA ARARIA CHANDERDEI ARARIA 20 100752 ARARIA KISHANGANJ LRP CHOWK, BAHADURGANJ BAHADURGANJ 21 100754 ARARIA KISHANGANJ SONTHA KOCHADHAMAN 22 100755 ARARIA KISHANGANJ JANTAHAT KOCHADHAMAN 23 100762 ARARIA ARARIA BIRNAGAR BHARGAMA 24 100766 ARARIA ARARIA GIDHBAS RANIGANJ 25 100767 ARARIA KISHANGANJ CHHATARGACHH POTHIA 26 100780 ARARIA ARARIA KUSIYARGAW ARARIA 27 100783 ARARIA ARARIA MAHATHWA. BHARGAMA 28 100785 ARARIA ARARIA PATEGANA. ARARIA 29 100786 ARARIA ARARIA JOGBANI FORBESGANJ 30 100794 ARARIA KISHANGANJ JHALA TERRAGACHH 31 100795 ARARIA ARARIA PARWAHA FORBESGANJ 32 100809 ARARIA KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ 33 100810 ARARIA KISHANGANJ -

Araria Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE ARARIA INTRODUCTION Araria, which was earlier a sub-division of Purina, became a full-fledged district on January 14, 1990, after the division of Purnia into three districts, namely Purnia, Araria and Kishanganj. This showery district of north-eastern Bihar is one of the most backward districts of Bihar, standing at the bottom of the 90 minority concentration districts. Borders of Araria are surrounded by Nepal in northern side, Kishanganj in eastern side and Supaul at western side. District border is adjacent to border of Nepal, so the district is important in terms of security. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The territory of the present-day district became Araria sub-division of the erstwhile Purnia district in 1964. In ancient times Araria was ruled by three important clans of Indian history. The important tribe of Kiratas governed the northern side, while the eastern side was under the Pundras and area west of the river Kosi, at that time flowing somewhere near the present Araria, by Angas. During the Mauryan period this area formed the part of the Mauryan Empire and according to Asokavadana the Emperor Asoka put to death many naked heretics of this area who had done despite to the Budhist religion. In the 6th century A.D. the area south of the Himalayan pilgrim center of Varaha Kshetra, namely the Gupta kings Budhgupta and Devagupta gave Koti-varsha for the maintenance of the said pilgrim centre. In the first war of independence of 1857 Araria also witnessed a few skirmishes between the mutineers and the commissioner Yule’s forces, which took place near Nathpur. -

Minutes of 7Th State Standing Committee Meeting

Minutes of 7th SSCM Meeting EASTERN REGIONAL POWER COMMITTEE MINUTES OF 7TH MEETING OF STANDING COMMITTEE ON TRANSMISSION PLANNING FOR STATE SECTORS HELD ON 01.07.2019 (MONDAY) AT 11:00 HOURS AT ERPC, KOLKATA List of participants is enclosed at Annexure-A. 1. Confirmation of minutes of 6th SSCM of ERPC held on 09.07.2018. The minutes were circulated vide letter dated 12.07.2018 to all the constituents and also uploaded in ERPC website. No comments have been received till date. Members may confirm the minutes. Deliberation in the meeting Members confirmed the minutes. New Transmission system proposals 1. Augmentation of transformation capacity at Muzaffarpur (POWERGRID) S/s – (Agenda by BSPTCL) BSPTCL has informed that the load in Muzaffarpur area is growing very fast. The load demand in Muzaffarpur & adjoining areas is largely fed by Muzaffarpur (PG) with transformation capacity of 1x500+2x315 MVA. During peak hours following loading is being observed: Present scenario: Sl. Maximum Lines NO. Load (MW) 1 Muzaffarpur (PG)-MTPS (D/C) 420 2 Muzaffarpur (PG)-Hazipur (D/C) 296 3 Muazaffarpur (PG)-Dhalkebar (Nepal) (400kV 150 Transmission Line charged at 220kV) Total 866 Future scenario: In future Amnor (Chappra) GSS(220/132/33 KV) will be connected to Muzaffarpur (PG) through 220 KV D/C lines as approved in 18th Standing Committee Meeting of CEA under 13th Plan. Further Amnor has been proposed to be connected to Digha (new) GSS (220/132/33 KV) at 220 KV level. BSPTCL has also proposed one 220/132/33 KV GSS at Garaul (Dist. Vaishali) under State Plan, approved in the Bihar cabinet, is getting source at 220 KV level with 1 Minutes of 7th SSCM Meeting D/C from Muzaffarpur(PG). -

SI. No. CSC ID Name Mobile Block Panchayat Center Address with Pin

SI. CSC ID Name Mobile Block Panchayat Center address with Pin code Email address No. 1 313124420019 Nitesh Kumar 8789331858 Araria Urban Raniganj road near power house om Nagar 854311 [email protected] 2 126463140012 hari kr yadav 9934193323 Araria Urban [email protected] 3 186478050011 rajendra raman 9661325578 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 4 219298890017 md Irshad alam 9431812188 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 5 241721320019 amit kumar sah 9102235005 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 6 244233510014 anurag kumar 9801792207 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 7 251257610017 AJAY KUMAR 9386390251 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 8 284534410019 AAMIR REZA 8539976165 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 9 325457470019 md danish 8581967245 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 10 333246270017 abhay shankar 9709886515 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 11 424374390018 Abdullah 7549540204 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 12 446208670011 Md Faisal Hoda 9572670823 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 13 456642730010 nadeem ahmad 8002168309 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 14 492453090014 shadab shamin 7562949594 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 15 496972920013 md imtiyaz rahi 9852606846 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 16 521385990016 santosh chaudhary 9308650915 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 17 552744560010 md reza shadab 9470722711 Araria Urban \N [email protected] 18 621753570018 md athar ghazi 9199636068 Araria Urban \N [email protected] -

KAMRAUL 05-.Xlsx

vkSioaf/kd es/kk lwph iapk;r f'k{kd fu;kstu bZdkb]Z xzke iapk;r jkt dejkSy iz[kaM ckjlksbZA QUALIFICATION % FATHER'S CANDIDATE DATE OF GENDE APPLY DATE /HUSBAN ADDRESS NAME BIRTH R POINT POINT SL.NO. APP. APP. NO. D'S NAME TET TYPE % % REMARKS % TRAINING NAME OF CATEGORY INSTITUTION TET TET WEITAGE INTER MERITMARKS TOTAL MERIT RESERVATION PASSING YEAR TRAINING TYPE MATRIC TET TET PERCENTAGE TRAINING 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 KUNDAN JANARDA 1 1 9/25/2019 12/5/1982 MADHEPURA MALE BC 44.28 62.66 76.11 61.02 66.00 2 63.02 B.ED CTET KUMAR N YADAV 2019 MD FIRDOS KAJRA, 2 2 9/27/2019 ZAINUL 12/21/1986 MALE 62.28 48.11 80.10 63.50 60.67 2 65.50 EBC B.ED CTET ALAM KATIHAR 2019 ABEDIN SUBHAM TANKA BARSOI, 3 3 9/28/2019 1/5/1993 MALE BC 57.80 56.40 79.46 64.55 62.00 2 66.55 B.ED CTET GHOSH GHOSH KATIHAR 2019 MANOJ MITHUN BARSOI , 4 4 9/28/2019 KUMAR 25.06.1989 MALE SC 63.42 55.33 75.76 64.84 60.66 2 66.84 B.ED CTET KUMAR DAS KATIHAR 2019 DAS KRISHNA JAIGOPAL MAHISAL, 5 5 9/28/2019 MOHAN 6/25/1986 MALE 55.43 47.00 70.06 57.50 55.00 2 59.50 EBC B.ED CTET DAS BALRAMPUR 2019 DAS MD DILAWER MD NIMOUL , 6 6 9/30/2019 30.12.1981 MALE 52.71 52.88 77.41 61.00 62.00 2 63.00 EWS B.ED CTET HUSSAIN YUNUS AZAMNAGAR 2019 MD SOHAR MD NAJIM 7 7 9/30/2019 KAMLUDD 31.12.1993 BARSOI, MALE BC 73.40 72.00 80.30 75.23 64.67 2 77.23 B.ED CTET ALAM 2019 IN KATIHAR MD GANJAN MD QUAIUM 8 8 10/16/2019 ASHFAQU 12/25/1994 BARSOI, MALE 55.8 55.00 77.69 62.83 62.83 UR ALI B.ED E ALAM KATIHAR MD EHSAN MD BARSOI, 9 9 15.02.1992 MALE 72.2 66.20 79.00 72.47