Cultural Arts As Economic Development: What Baltimore Can Learn from Charlotte, N.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

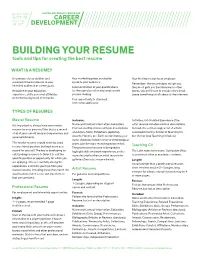

BUILDING YOUR RESUME Tools and Tips for Creating the Best Resume

BUILDING YOUR RESUME tools and tips for creating the best resume WHAT IS A RESUME? • A summary of your abilities and • Your marketing piece, curated to • Your first impression to an employer. accomplishments relevant to your speak to your audience. • Remember: the resume does not get you intended audience or career goals. • A demonstration of your qualifications the job—it gets you the interview. In other • An outline of your education, for the type of position and employment words, you don’t have to include every detail. experience, skills, personal attributes you are seeking. Leave something to talk about at the interview. and other background information. • Your opportunity to stand out from other applicants . TYPES OF RESUMES Master Resume Includes: Activities, Art- Related Experience (The It is important to always have one master Name and Contact Information, Education, artist resume includes minimal descriptions. resume for your personal files that is a record Professional Experience with job descriptions Instead, it is a chronological list of artistic of all of your current and past experiences and and duties, Skills, Exhibitions (optional), accomplishments). Similar to Teaching CV, accomplishments. Awards, Honors, etc. Each section below your but shorter (see Teaching CV below). name should be listed in reverse chronological This master resume should never be used order, with the most recent experience first. Teaching CV for any official position, but kept more as a The professional resume is designed to record for yourself. The key to developing an highlight skills and work experience, so it is The Latin name for resume, Curriculum Vitae, outstanding resume is to tailor it to suit the more descriptive than an artist resume for is used most often in academic contexts. -

IEDC Excellence in Economic Development Awards

AWARDS IEDC Excellence in Economic Development Awards IEDC’s professional economic development awards Honorary & Leadership Awards will be presented recognize excellence in the economic development at the Recognition Dinner on Monday, September profession. These prestigious awards honor 19 from 6:30 P.M. – 9:00 P.M. at the Mint Museum individuals and organizations for their efforts that UPTOWN, 500 South Tryon Street, Charlotte, NC. have created positive change in urban, suburban, and Please note the registration fee of $100. rural communities. Promotional & Program Awards will be presented during the Awards Ceremony on Tuesday, September 20 from 3:45 P.M. – 5:45 P.M. in the Convention Center Ballroom. 91 2011 AWARD CATEGORIES IEDC 2011 ANNUAL CONFERENCE CONFERENCE IEDC 2011 ANNUAL HONORARY & LEADERSHIP AWARDS ...................................................................................92 Fellow Member Designations .................................................................................................................92 Honorary Life Member Designation .......................................................................................................94 New Economic Development Professional of the Year ..........................................................................94 Leadership Award for Public Service ......................................................................................................95 Citizen Leadership Award .......................................................................................................................96 -

PAUL DANIEL 1623 Bolton Street, Baltimore, MD 21217 Cell: 443-691-9764 Email: [email protected]

PAUL DANIEL 1623 Bolton Street, Baltimore, MD 21217 Cell: 443-691-9764 email: [email protected] https://bakerartist.org/node/921 SELECTED PUBLIC ART: 2019 Art on the Waterfront commission, Middle Branch Park, Balt Office of Promotion & the Arts 2015 Finalist for Art-in-Transit, Redline, Mass Transit Administration Finalist for Art-in-Transit, Purple Line, Mass Transit Administration 2014-15 Manolis, Cylburn Arboretum 2013 Finalist Unity Parkside Public Art, DC Commission on the Arts & Humanities 2009-’16 Flirting with Memory on exhibition at Johns Hopkins BayvieW Hospital, Baltimore, MD 2007-’16 Kiko-Cy on exhibit for the Baltimore Office of Promotion and Tourism, St Paul St median 1997 Oak Leaf Gazebo, Mitchellville, MD, Collaboration With artist Linda DePalma; Rocky Gorge Communities Commission 1992 Naiad's Pool, Rockcrest Ballet Center & Park, Rockville, MD; Art in Public Places 1991 Double Gamut, Franklin Street Parking Garage, Baltimore, MD, Baltimore 1% for Art Jack Tar’s Fancy, Snug Harbor Cultural Center, Staten Island, NY, Collaboration With artist Linda DePalma; Curator: Olivia Georgia 1990 Sun Arbor & Moon Arbor, Quiet Waters Park, Annapolis, MD Collaboration With artist Linda DePalma; Anne Arundel Co. Dept. of Parks & Recreation; Art Consultant: Cindy Kelly 1987 Goal Keeper, William Myers Pavilion, Brooklyn, MD; Baltimore 1% for Art Program 1985 Messenger, Clifton T. Perkins Hospital, Jessup, MD; MD State Fine Art in Public Places 1984 Venter, State Center Metro Station, Baltimore, MD; Mass Transit Administration 1978 Titan, Liberty Elementary School, Baltimore, MD; Baltimore 1% for Art Program ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS: 2018 Acknowledging the Wind: Kinetic SculPtures by Paul Daniel, LadeW Topiary Gardens, Monkton, MD 2015 On & Off the Wall: 3D & 2D work by Paul Daniel, Project 1628, Baltimore, MD 2009 Paul Daniel-Current Reflection, Katzen Art Museum, American University, DC 2010 2000 Paul Daniel- Kinetic SculPtures in the Pond, The Park School, Brooklandville, MD 1990 Paul Daniel- Recent SculPture, C. -

Art Seminar Group 1/29/2019 REVISION

Art Seminar Group 1/29/2019 REVISION Please retain for your records WINTER • JANUARY – APRIL 2019 Tuesday, January 8, 2019 GUESTS WELCOME 1:30 pm Central Presbyterian Church (7308 York Road, Towson) How A Religious Rivalry From Five Centuries Ago Can Help Us Understand Today’s Fractured World Michael Massing, author and contributor to The New York Review of Books Erasmus of Rotterdam was the leading humanist of the early 16th century; Martin Luther was a tormented friar whose religious rebellion gave rise to Protestantism. Initially allied in their efforts to reform the Catholic Church, the two had a bitter falling out over such key matters as works and faith, conduct and creed, free will and predestination. Erasmus embraced pluralism, tolerance, brotherhood, and a form of the Social Gospel rooted in the performance of Christ-like acts; Luther stressed God’s omnipotence and Christ’s divinity and saw the Bible as the Word of God, which had to be accepted and preached, even if it meant throwing the world into turmoil. Their rivalry represented a fault line in Western thinking - between the Renaissance and the Reformation; humanism and evangelicalism - that remains a powerful force in the world today. $15 door fee for guests and subscribers Tuesday, January 15, 2019 GUESTS WELCOME 1:30 pm Central Presbyterian Church (7308 York Road, Towson) Le Jazz Hot: French Art Deco Bonita Billman, instructor in Art History, Georgetown University What is Art Deco? The early 20th-century impulse to create “modern” design objects and environments suited to a fast- paced, industrialized world led to the development of countless expressions, all of which fall under the rubric of Art Deco. -

A Community Views Its Future--Civic

Baltim"[lnaqrland Metropofitan ("gion A Community Views Its Future Baltim"filnaryland Metropolitan R.gion Civic Leaders' Strategies for Economic Prosperity and Quality of Life in the 2Lst Century A HUD Report on Metropolitan Economic StrategJr U.S. Department of Housing *d Urban Development May L997 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT WASHTNGTON. D.C. 204 t O-OOOI THE SECRETARY In America today, nearly 80 percent of the population and almost 9 0 percent of the employment growth is in metropol it,an regions. We are individuals and families looking to the future for good jobs and business opportunities, for rising incomes to owrr homes, for children to get a worthwhile education, for communities to thrive in health and safety. A11 cf us share a common fate in a new metropolitan economy that will determine our nation' s prosperity and guality of l-if e in the 21-st Century. This New Economy knowledge and informat,ion-based, technology-intensive, and gIobally oriented demands new skills in education, research, and workforce developmenE. To be competitive now reguires regional collaboration and innovative leadership: a Metropolit.an Economic Strategy f or investment in transportation and infrastructure, environmentaL preservation, and community revitalization Our report A Communitv Views fts Future is the resul-t of extensive locai research and interviews, including my recent visit and meetings with metropoliEan leadership. You have told us where you are headed as a region, and how t,he f ederal government can be more helpful in servincr your present and future needs. We have worked with you to identify metropolitan Baltimore' s engrines of prosperity: the industry clusters Lhat can creat.e better j obs and business opportunities . -

RENEE VAN DER STELT Baldwin, MD 21013 [email protected]

RENEE VAN DER STELT Baldwin, MD 21013 www.reneevanderstelt.com [email protected] EDUCATION M.F.A. Drawing 1993, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA M.A. Art History 1990, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA M.A. Studio & Art History 1988, Calvin College, Grand Rapids, MI Foreign Language & Art History 1985, Free University, Amsterdam, NL SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Neck of the Woods: Marrow, Elon University, Elon, MD What Lies Beneath, China Hutch Project Chestertown, MD 2016-17 Tremor in Shadow, Project 1628, Baltimore, MD 2016 Black Box / Adjacent Body, Lenka Clayton’s Motherhood Residency Exhibition Project. Baldwin, MD, November, 2016 2016 How to Draw the Wind, Sandbox, Chestertown, MD 2015 Borders & Migration: Shifting Geographies, Doris Ulmann Galleries, Berea College, Berea, KY, 2015 2010 Recordings, Hamiltonian Gallery, Washington DC Sphere Charts & Site Drawings, GalleryOne, Ellensburg, WA Drawing Movement on Land, Montpelier Arts Center, Laurel, MD Veiled Geography: Impermanent Drawings, Colburn Gallery, Burlington, VT 2009 Fugitive Drawings, Creative Alliance, Baltimore, MD 2009 Projections: Line on Land, Target Gallery, Alexandria, VA 2009 Global/Local, Roswell Museum and Art Center, Roswell, NM 2009 2005 Drawing Imagined Space, School 33, Baltimore, MD 2005 Pin Drawings, SPARE ROOM, Baltimore, MD 2004 Drawing to Space, Millersville University, Millersville, PA 2003 Recent Sculptures/Drawings, Berea College, Berea, KY 1998 7 Dresses on a Hill, 7 Hands in Shade, 7 Paintings in Trees, Faber’s Farm, Parnell, IA 1996 Transitions, -

Curriculum Vitae 3413 Nancy Ellen Way Owings Mills, Maryland 21117-1513 (410) 654-0077 • E-Mail: [email protected] •

Helen Glazer | Curriculum Vitae 3413 Nancy Ellen Way Owings Mills, Maryland 21117-1513 (410) 654-0077 • E-mail: [email protected] • http://helenglazer.com Exhibitions (*=award received): 2020 Selections from Helen Glazer's Antarctica Archive, Center for Art + Environment, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, NV. Curator: Sara Frantz. 2019 Leonardo: When the Arts Reach the Sky. Baltimore-Washington International Marshall Airport, Baltimore, MD. Curator: Gioia Milano. 2nd Triannual Maryland State Arts Registry Juried Show, Maryland Art Place, Baltimore, MD. Jurors: Susan J. Isaacs and Jeremy Stern. Women's Work, Full Circle Fine Art, Baltimore, MD. Curator: Brian Miller. Antarctica Sculpture by Helen Glazer, Towers Crescent, Tysons Corner, VA. Curator: Craig Schaffer. 2018 Art on the Fly, Maryland State Arts Council, Baltimore, MD. Curators: Maryland State Arts Council staff. Abstraction at Large. Site: Brooklyn, Brooklyn, NY. Juror: Eleanor Heartney. Anthropocene. Safe Harbors Ann Street Gallery, Newburgh, NY. Curator: Virginia West. 2017-18 Helen Glazer: Walking in Antarctica. Rosenberg Gallery, Goucher College, Baltimore, MD. Science Inspires Art: Ocean. New York Hall of Science, Queens, NY. BWI Marshall Airport Exhibit. Two photographs enlarged to 7 x 10 feet. Jurors: Yumi Hogan, Jinchul Kim, Rex Stevens, Tony Shore, Zoë Charlton (Jul. 2017-Aug. 2018). 2017 2017 Trawick Prize: Bethesda Contemporary Arts Finalists Exhibition, Gallery B, Bethesda, MD. Jurors: Zoë Charlton, Neil Feather, Elizabeth Mead. Field Work: An Artscape 2017 Exhibition. Pinkard Gallery, Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore. Curator: Kim Domanski. Embedded Sources. Full Circle Gallery, Baltimore, MD. Curator: Brian Miller. Sculpture Remix 2017: Craft/Technology/Art. Arcade Gallery at Glen Echo National Park, Glen Echo, MD. -

Carolyn Case Lives and Works in Baltimore, MD

Carolyn Case Lives and works in Baltimore, MD. Education 1997 Maryland Institute College of Art, MFA, Baltimore, MD 1994 California State University, BFA, Long Beach, CA Solo Exhibitions 2021 Reynolds Gallery, “Test Kitchen”, Richmond, VA 2020 Asya Geisberg Gallery, “Before It Sinks In”, New York, NY 2019 Lux Art Institute, Encinitas, CA 2019 Western Michigan University, “Second Thoughts”, Kalamazoo, MI 2017 Asya Geisberg Gallery, “Homemade Tattoo”, New York, NY 2015 Asya Geisberg Gallery, “Heat and Dust”, New York, NY Maryland Institute College of Art, “Carolyn Case”, Baltimore, MD 2012 Loyola University, “Altered States”, Baltimore, MD 2011 McLean Projects for the Arts, “Accidentally On Purpose”, Washington, D.C. 2010 The Art Registry, “Travels”, Washington, D.C. 2005 School 33, “Carolyn Case”, Baltimore, MD 2004 The Arts Club of Washington, “Carolyn Case”, Washington, D.C. 2002 Maryland Art Place, “Just Paint”, Baltimore, MD Group Exhibitions 2019 Maryland Art Place, “Maryland State Artist Registry Exhibition”, Baltimore, MD School 33, “40th Anniversary Exhibition”, Baltimore, MD United States Embassy, “Art in Embassies”, curated by Camille Benton, Managua, Nicaragua 2018 BWI Airport, “People & Places”, Baltimore, MD Maryland Institute College of Art, “MICA Sabbatical Exhibition”, Baltimore, MD 2017 Walters Art Museum, Maryland Institute College of Art, “Sondheim Artscape Prize Semi-Finalist Exhibition”, Baltimore, MD 2016 Decker and Meyerhoff Galleries, MICA, “Sondheim Artscape Prize Semi-Finalist Exhibition”, Baltimore, MD Sindikit Gallery, “Sindikit #3”, curated by Zoe Charlton and Tim Doud, Baltimore, MD 2015 Maryland Institute College of Art, “Juried Faculty Exhibition”, curated by Barry Schwabsky, Baltimore, MD 2014 The Parlour Bushwick, “Show #12”, New York, NY Heurich Gallery, Washington, D.C. -

Beyond Boxers Or Briefs Educate Early, Vote Often by Joshua Levy an Interview with Civicyouth.Org’S Peter Levine Letters to the Editor

CHAPTER NEWS MEMBER NEWS AND MORE TVNNFS 2008 :PVOH7PUFST "DUJWJTUTBSF3FBEZUPCF)FBSE .JTTJPOUP.BOHV[J QH $BMMFEUP"GSJDB 8F'PVOE0VSTFMWFT CZ#SJDF/JFMTFO 04 .FNPJSTPGB4USFFU.BSDIFS QH 12 .Z"DUJWJTNJO3FUSPTQFDU CZ+PTF%BMJTBZ+S #FZPOE#PYFSTPS#SJFGT "DUJWJTU 5FDI8BUDIFS+PTIVB-FWZ QH 14 5BDLMFT/FX.FEJBBOE1PMJUJDT &EVDBUF&BSMZ 7PUF0GUFO $SVODIJOHUIF/VNCFST QH 18 XJUI$*3$-&µT1FUFS-FWJOF The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the staff of Phi Kappa Phi Forum or the Board of Directors of The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi. phi kappa phi forum (issn 1538-5914) is published quarterly by The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, 7576 Goodwood Blvd., Baton Rouge, la 70806. Printed at R.R. Donnelley, 1160 N. Main, Pontiac, il 61764. the honor society of phi kappa phi was founded in ©The Honor Society of Phi 1897 and became a national organization through the Kappa Phi, 008. All rights efforts of the presidents of three state universities. Its reserved. Non-member primary objective has from the first been the recognition subscriptions $30 per and encouragement of superior scholarship in all fields of year. Single copies $10 study. Good character is an essential supporting attribute each. Periodicals postage for those elected to membership. The motto of the Society paid Baton Rouge, la and additional mailing is phiosophia krateito phótón, which is freely translated as offices. Material intended “Let the love of learning rule humanity.” for publication should be Phi Kappa Phi encourages and recognizes academic addressed to Traci Navarre, excellence through several programs. Through its The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, 7576 Goodwood awards and grants programs, the Society each triennium Blvd., Baton Rouge, la 70806. -

MEDA in ACTION Annual Report for FY 2018-19 Letter from MEDA Chairman/CEO and Mayor

MEDA IN ACTION Annual Report for FY 2018-19 Letter from MEDA Chairman/CEO and Mayor August 2019 Greetings Maricopans, Maricopa is burgeoning, and the prospects for our future have never been brighter! Fiscal Year 2018-19 has brought positive, pivotal change and progress for our great city and our citizens. National name brand retail stores and restaurants have located new facilities in Maricopa. Apex Motor Club broke ground on its motorsports country club. Our Copper Sky Commercial Complex and Estrella Gin Business Park soon will be breaking ground. La Quinta Hotels announced it will be building a hotel in our city. Ak-Chin Harrah’s Hotel and Casino completed its three-year, multi-million dollar renovation and expansion, and marked its 25th anniversary. Our local economy is stable and growing responsibly, and the Maricopa City Councilmembers are committed to ensuring that Maricopa’s business and investment environment supports quality enterprises and jobs. All Maricopans are rightfully proud of this wonderful community they call home. Our residents and businesses have made invaluable contributions to the Maricopa of today — a city that offers an unparalleled, outstanding and safe quality of life; a vibrant spirit of community service, and strong public-private partnerships in which citizens, business, government and education work together to build a strong and diverse local economy and community. The Maricopa-MEDA partnership is a critically important cornerstone to our economic vitality and sustainability. Through the Maricopa Economic Development Alliance, the City of Maricopa and business and education leaders join forces to identify and support promising economic development opportunities. -

Program Speakers 2014 Awards Sponsors & Exhibitors

FAQS | CONTACT | ABOUT IEDC | IEDC HOME | FOLLOW IEDC: ShareShareShareShareMore595 SHARE: More595 REGISTRATION HOTEL & TRAVEL PROGRAM SPEAKERS 2014 AWARDS SPONSORS & EXHIBITORS Program Select the " " icon to learn more about a session or special event. $ = Extra fee event Wednesday, October 15 8:30 am - 5:00 pm Professional Development Course: Economic Development Credit Analysis $ Thursday, October 16 8:30 am - 6:30 pm Professional Development Course: Economic Development Credit Analysis $ Friday, October 17 8:30 am - 4:30 pm Professional Development Course: Economic Development Credit Analysis $ Saturday, October 18 7:00 am - 9:30 pm Certified Economic Developers (CEcD) Exam $ 1:00 pm Golf Tournament at Mira Vista Country Club SOLD OUT 2:30 pm - 5:30 pm More Than Just a Football Stadium: AT&T Stadium Tour $ Sunday, October 19 8:00 am - 7:30 pm Registration 8:00 am - 12:00 pm Explore Fort Worth's Trinity River Vision on Horseback and Wagon (Sunday) $ 10:30 am - 12:30 pm Ethics Workshop 12:00 pm - 1:30 pm Learning Lab A: Master Class: LinkedIn for Economic Developers Learning Lab B: Accelerating Results and Avoiding Dead Ends on Major Projects: New Tools and Methods for Community Stakeholder Alignment 1:00 pm - 7:30 pm Economic Development Marketplace 2:00 pm - 3:30 pm Opening Plenary Session 3:30 pm - 6:00 pm Tour: Bus Tour of AllianceTexas $ 3:45 pm - 5:15 pm Panel Discussions: NAFTA at 20: Capturing Increased Near Shoring Opportunities Driving Value through the New Economics of Place The Energy Play: Fracking and Natural Gas from A-Z -

The Metropolitan Governance Process in Greater Baltimore

PRELIMINARY DRAFT REPORT Engendering Innovative Urban Strategies in a New Regionalism Era: The Metropolitan Governance Process in Greater Baltimore Eric Champagne INRS- Urbanisation Montreal International Urban Fellow Report Institute for Policy Studies Johns Hopkins University Baltimore November 10,1999 Eric Champagne PhD. Candidate Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS-urbanisat ion) Universitk du Quebec 3465, rue Durocher Montrkal (Qukbec) Canada H2X 2C6 Telephone: (5 14) 499-4078 Fax: (5 14) 499-4065 E-Mail: eric-champagne@inr s-urb .uquebec.ca .. 11 Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. A Portrait of Industrial City Regions: Problems and Concepts ................................................................................ 6 1.1 The Urban Restructuring Process (structuralfactors) ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1 Economic restructuring ..................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.2 Globalization process ...................................................................................................................................... 10 1.1.3 Spatial transformation of city regions ............................................................................................................