565273-Rinfret.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Four Courts of Sir Lyman Duff

THE FOUR COURTS OF SIR LYMAN DUFF RICHARD GOSSE* Vancouver I. Introduction. Sir Lyman Poore Duff is the dominating figure in the Supreme Court of Canada's first hundred years. He sat on the court for more than one-third of those years, in the middle period, from 1906 to 1944, participating in nearly 2,000 judgments-and throughout that tenure he was commonly regarded as the court's most able judge. Appointed at forty-one, Duff has been the youngest person ever to have been elevated to the court. Twice his appointment was extended by special Acts of Parliament beyond the mandatory retirement age of seventy-five, a recogni- tion never accorded to any other Canadian judge. From 1933, he sat as Chief Justice, having twice previously-in 1918 and 1924 - almost succeeded to that post, although on those occasions he was not the senior judge. During World War 1, when Borden considered resigning over the conscription issue and recommending to the Governor General that an impartial national figure be called upon to form a government, the person foremost in his mind was Duff, although Sir Lyman had never been elected to public office. After Borden had found that he had the support to continue himself, Duff was invited to join the Cabinet but declined. Mackenzie King con- sidered recommending Duff for appointment as the first Canadian Governor General. Duff undertook several inquiries of national interest for the federal government, of particular significance being the 1931-32 Royal Commission on Transportation, of which he was chairman, and the 1942 investigation into the sending of Canadian troops to Hong Kong, in which he was the sole commissioner . -

Special Series on the Federal Dimensions of Reforming the Supreme Court of Canada

SPECIAL SERIES ON THE FEDERAL DIMENSIONS OF REFORMING THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA The Supreme Court of Canada: A Chronology of Change Jonathan Aiello Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University SC Working Paper 2011 21 May 1869 Intent on there being a final court of appeal in Canada following the Bill for creation of a Supreme country’s inception in 1867, John A. Macdonald, along with Court is withdrawn statesmen Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Mackenzie and Edward Blake propose a bill to establish the Supreme Court of Canada. However, the bill is withdrawn due to staunch support for the existing system under which disappointed litigants could appeal the decisions of Canadian courts to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) sitting in London. 18 March 1870 A second attempt at establishing a final court of appeal is again Second bill for creation of a thwarted by traditionalists and Conservative members of Parliament Supreme Court is withdrawn from Quebec, although this time the bill passed first reading in the House. 8 April 1875 The third attempt is successful, thanks largely to the efforts of the Third bill for creation of a same leaders - John A. Macdonald, Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Supreme Court passes Mackenzie and Edward Blake. Governor General Sir O’Grady Haly gives the Supreme Court Act royal assent on September 17th. 30 September 1875 The Honourable William Johnstone Ritchie, Samuel Henry Strong, The first five puisne justices Jean-Thomas Taschereau, Télesphore Fournier, and William are appointed to the Court Alexander Henry are appointed puisne judges to the Supreme Court of Canada. -

Canadian Law Library Review Revue Canadienne Des Bibliothèques Is Published By: De Droit Est Publiée Par

CANADIAN LAW LIBRARY REVIEW REVUE CANADIENNE DES BIBLIOTHÈQUES DE DROIT 2017 CanLIIDocs 227 VOLUME/TOME 42 (2017) No. 2 APA Journals® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY 2017 CanLIIDocs 227 Law and Human Behavior® Official Journal of APA Division 41 (American Psychology-Law Society) Bimonthly • ISSN 0147-7307 2.884 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.542 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychological Assessment® Monthly • ISSN 1040-3590 3.806 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.901 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychology, Public Policy, and Law® Quarterly • ISSN 1076-8971 2.612 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 1.986 2015 Impact Factor®* Journal of Threat Assessment and Management® Official Journal of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals, the Canadian Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and the Asia Pacific Association of Threat Assessment Professionals Quarterly • ISSN 2169-4842 * ©Thomson Reuters, Journal Citation Reports® for 2015 ENHANCE YOUR PSYCHOLOGY SERIALS COLLECTION To Order Journal Subscriptions, Contact Your Preferred Subscription Agent American Psychological Association | 750 First Street, NE | Washington, DC 20002-4242 USA ‖‖ CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE 5 From the Editor The Law of Declaratory Judgments 40 De la rédactrice Reviewed by Melanie R. Bueckert 7 President’s Message Pocket Ontario OH&S Guide to Violence and 41 Le mot de la présidente Harassment Reviewed by Megan Siu 9 Featured Articles Articles de fond Power of Persuasion: Essays -

Canadian Law Library Review Revue Canadienne Des Bibliothèques Is Published By: De Droit Est Publiée Par

CANADIAN LAW LIBRARY REVIEW REVUE CANADIENNE DES BIBLIOTHÈQUES DE DROIT VOLUME/TOME 42 (2017) No. 2 APA Journals® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY Law and Human Behavior® Official Journal of APA Division 41 (American Psychology-Law Society) Bimonthly • ISSN 0147-7307 2.884 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.542 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychological Assessment® Monthly • ISSN 1040-3590 3.806 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.901 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychology, Public Policy, and Law® Quarterly • ISSN 1076-8971 2.612 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 1.986 2015 Impact Factor®* Journal of Threat Assessment and Management® Official Journal of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals, the Canadian Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and the Asia Pacific Association of Threat Assessment Professionals Quarterly • ISSN 2169-4842 * ©Thomson Reuters, Journal Citation Reports® for 2015 ENHANCE YOUR PSYCHOLOGY SERIALS COLLECTION To Order Journal Subscriptions, Contact Your Preferred Subscription Agent American Psychological Association | 750 First Street, NE | Washington, DC 20002-4242 USA ‖‖ CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE 5 From the Editor The Law of Declaratory Judgments 40 De la rédactrice Reviewed by Melanie R. Bueckert 7 President’s Message Pocket Ontario OH&S Guide to Violence and 41 Le mot de la présidente Harassment Reviewed by Megan Siu 9 Featured Articles Articles de fond Power of Persuasion: Essays by a Very Public 41 Edited by John -

1050 the ANNUAL REGISTER Or the Immediate Vicinity. Hon. E. M. W

1050 THE ANNUAL REGISTER or the immediate vicinity. Hon. E. M. W. McDougall, a Puisne Judge of the Superior Court for the Province of Quebec: to be Puisne Judge of the Court of King's Bench in and for the Province of Quebec, with residence at Montreal or the immediate vicinity. Pierre Emdle Cote, K.C., New Carlisle, Que.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Superior Court in and for the Province of Quebec, effective Oct. 1942, with residence at Quebec or the immediate vicinity. Dec. 15, Henry Irving Bird, Vancouver, B.C.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, with residence at Vancouver, or the immediate vicinity. Frederick H. Barlow, Toronto, Ont., Master of the Supreme Court of Ontario: to be a Judge of the High Court of Justice for Ontario. Roy L. Kellock, K.C., Toronto, Ont.: to be a Justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and ex officio a Judge of the High Court of Juscico for Ontario. 1943. Feb. 4, Robert E. Laidlaw, K.C., Toronto, Ont.: to be a Justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and ex officio a Judge of the High Court of Justice for Ontario. Apr. 22, Hon. Thane Alexander Campbell, K.C., Summer- side, P.E.I.: to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature of P.E.I. Ivan Cleveland Rand, K.C., Moncton, N.B.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Canada. July 5, Hon. Justice Harold Bruce Robertson, a Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia: to be a Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal for British Columbia. -

A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962

8 A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962 When the newly paramount Supreme Court of Canada met for the first timeearlyin 1950,nothing marked theoccasionasspecial. ltwastypicalof much of the institution's history and reflective of its continuing subsidiary status that the event would be allowed to pass without formal recogni- tion. Chief Justice Rinfret had hoped to draw public attention to the Court'snew position throughanotherformalopeningofthebuilding, ora reception, or a dinner. But the government claimed that it could find no funds to cover the expenses; after discussing the matter, the cabinet decided not to ask Parliament for the money because it might give rise to a controversial debate over the Court. Justice Kerwin reported, 'They [the cabinet ministers] decided that they could not ask fora vote in Parliament in theestimates tocoversuchexpensesas they wereafraid that that would give rise to many difficulties, and possibly some unpleasantness." The considerable attention paid to the Supreme Court over the previous few years and the changes in its structure had opened broader debate on aspects of the Court than the federal government was willing to tolerate. The government accordingly avoided making the Court a subject of special attention, even on theimportant occasion of itsindependence. As a result, the Court reverted to a less prominent position in Ottawa, and the status quo ante was confirmed. But the desire to avoid debate about the Court discouraged the possibility of change (and potentially of improvement). The St Laurent and Diefenbaker appointments during the first decade A Decade of Adjustment 197 following termination of appeals showed no apparent recognition of the Court’s new status. -

The Judicial Function Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky

The Judicial Function under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky* The author surveys the various American L'auteur resume les differentes theories am6- theories of judicial review in an attempt to ricaines du contr61e judiciaire dans le but de suggest approaches to a Canadian theory of sugg6rer une th6orie canadienne du r8le des the role of the judiciary under the Canadian juges sous Ia Charte canadiennedes droits et Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A detailed libert~s. Notamment, une 6tude d6taille de examination of the legislative histories of sec- 'histoire 1fgislative des articles 1, 52 et 33 de ]a Charte d6montre que les r~dacteurs ont tions 1, 52 and 33 of the Charterreveals that voulu aller au-delA de la Dclarationcana- the drafters intended to move beyond the Ca- dienne des droits et 6liminer le principe de ]a nadianBill ofRights and away from the prin- souverainet6 parlementaire. Cette intention ciple of parliamentary sovereignty. This ne se trouvant pas incorpor6e dans toute sa intention was not fully incorporated into the force au texte de Ia Charte,la protection des Charter,with the result that, properly speak- droits et libert~s au Canada n'est pas, Apro- ing, Canada's constitutional bill of rights is prement parler, o enchfiss~e )) dans ]a cons- not "entrenched". The author concludes by titution. En conclusion, l'auteur met 'accent emphasizing the establishment of a "contin- sur l'instauration d'un < colloque continu uing colloquy" involving the courts, the po- auxquels participeraient les tribunaux, les litical institutions, the legal profession and institutions politiques, ]a profession juri- society at large, in the hope that the legiti- dique et le grand public; ]a l6gitimit6 de la macy of the judicial protection of Charter protection judiciaire des droits garantis par rights will turn on the consent of the gov- la Charte serait alors fond6e sur la volont6 erned and the perceived justice of the courts' des constituants et Ia perception populaire de decisions. -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

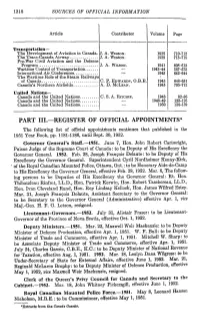

PART III.—REGISTER of OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* the Following List of Official Appointments Continues That Published in the 1951 Year Book, Pp

1218 SOURCES OF OFFICIAL INFORMATION Article Contributor Volume Page Transportation— The Development of Aviation in Canada. J. A. WILSON. 1938 710-712 The Trans-Canada Airway J. A. WILSON. 1938 713-715 Pre-War Civil Aviation and the Defence Program J. A. WILSON. 1941 608-612 Wartime Control of Transportation 1943-14 567-575 International Air Conferences 1945 642-644 The Wartime Role of the Steam Railways of Canada C. P. EDWARDS, O.B.E. 1945 648-651 Canada's Northern Airfields A. D. MCLEAN. 1945 705-712 United Nations- Canada and the United Nations C. S. A. RITCHIE. 1946 82-86 Canada and the United Nations 1948-49 122-125 Canada and the United Nations 1950 134-139 PART III.—REGISTER OF OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* The following list of official appointments continues that published in the 1951 Year Book, pp. 1181-1186, until Sept. 30, 1952. Governor General's Staff.—1951. June 7, Hon. John Robert Cartwright, Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Canada: to be Deputy of His Excellency the Governor General. 1952. Feb. 28, Joseph Francois Delaute: to be Deputy of His Excellency the Governor General. Superintendent Cyril Nordheimer Kenny-Kirk, of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Ottawa, Ont.: to be Honorary Aide-de-Camp to His Excellency the Governor General, effective Feb. 28, 1952. Mar. 6, The follow ing persons to be Deputies of His Excellency the Governor General: Rt. Hon. Thibaudeau Rinfret, LL.D., Hon. Patrick Kerwin, Hon. Robert Taschereau, LL.D., Hon. Ivan Cleveland Rand, Hon. Roy Lindsay Kellock, Hon. James Wilfred Estey. Mar. -

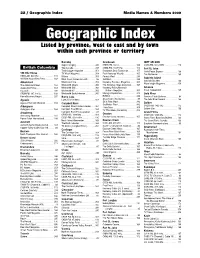

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Mcgill Law Journal Revuede Droitde Mcgill

McGill Revue de Law droit de Journal McGill Vol. 50 DECEMBER 2005 DÉCEMBRE No 4 SPECIAL ISSUE / NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL NAVIGATING THE TRANSSYSTEMIC TRACER LE TRANSSYSTEMIQUE Where Law and Pedagogy Meet in the Transsystemic Contracts Classroom Rosalie Jukier* In this article, the author examines how the Dans cet article, l’auteure examine comment transsystemic McGill Programme, predicated on a fonctionne «sur le terrain», dans un cours d’Obligations uniquely comparative, bilingual, and dialogic contractuelles de première année, le programme theoretical foundation of legal education, operates “on transsystémique de McGill, bâti sur des fondements the ground” in a first-year Contractual Obligations théoriques de l’éducation juridique qui sont à la fois classroom. She describes generally how the McGill comparatifs, bilingues, et dialogiques. Elle explique Programme distinguishes itself from other comparative comment, de manière générale, le programme de or interdisciplinary projects in law, through its focus on McGill se distingue d’autres projets juridiques integration rather than on sequential comparison, as comparatifs ou interdisciplinaires, de par son insistance well as its attempt to link perspectives to mentalités of sur l’intégration plutôt que sur la comparaison different traditions. The author concludes with a more séquentielle, ainsi que de par son objectif de relier les detailed study of the area of specific performance as a perspectives et mentalités propres à différentes particular application of a given legal phenomenon in traditions. L’auteure conclut avec une étude plus different systemic contexts. approfondie de la doctrine de «specific performance» en tant qu’application spécifique dans divers contextes systémiques d'un phénomène juridique donné. * Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, McGill University. -

Historical Portraits Book

HH Beechwood is proud to be The National Cemetery of Canada and a National Historic Site Life Celebrations ♦ Memorial Services ♦ Funerals ♦ Catered Receptions ♦ Cremations ♦ Urn & Casket Burials ♦ Monuments Beechwood operates on a not-for-profit basis and is not publicly funded. It is unique within the Ottawa community. In choosing Beechwood, many people take comfort in knowing that all funds are used for the maintenance, en- hancement and preservation of this National Historic Site. www.beechwoodottawa.ca 2017- v6 Published by Beechwood, Funeral, Cemetery & Cremation Services Ottawa, ON For all information requests please contact Beechwood, Funeral, Cemetery and Cremation Services 280 Beechwood Avenue, Ottawa ON K1L8A6 24 HOUR ASSISTANCE 613-741-9530 • Toll Free 866-990-9530 • FAX 613-741-8584 [email protected] The contents of this book may be used with the written permission of Beechwood, Funeral, Cemetery & Cremation Services www.beechwoodottawa.ca Owned by The Beechwood Cemetery Foundation and operated by The Beechwood Cemetery Company eechwood, established in 1873, is recognized as one of the most beautiful and historic cemeteries in Canada. It is the final resting place for over 75,000 Canadians from all walks of life, including im- portant politicians such as Governor General Ramon Hnatyshyn and Prime Minister Sir Robert Bor- den, Canadian Forces Veterans, War Dead, RCMP members and everyday Canadian heroes: our families and our loved ones. In late 1980s, Beechwood began producing a small booklet containing brief profiles for several dozen of the more significant and well-known individuals buried here. Since then, the cemetery has grown in national significance and importance, first by becoming the home of the National Military Cemetery of the Canadian Forces in 2001, being recognized as a National Historic Site in 2002 and finally by becoming the home of the RCMP National Memorial Cemetery in 2004.