Journal Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement of Investment Holdings Dec. 31, 2016

1 DEUTSCHE TELEKOM AG STATEMENT OF INVESTMENT HOLDINGS IN ACCORDANCE WITH § 285 HGB AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2016 1. Subsidiaries Shareholders’ equity Indirectly Directly Total thousands of Net income/net loss Reporting No. Name and registered office Via % % nominal value Currency reporting currency thousands of € currency Note 1. 3.T-Venture Beteiligungsgesellschaft mbH (3. TVB), Bonn 1.93. 100.00 25,000 EUR 6,382 764 EUR e) 2. Antel Germany GmbH, Karben 1.105. 100.00 25,000 EUR (119) (48) EUR i) 3. Arbeitgeberverband comunity, Arbeitgeberverband für EUR - - EUR Telekommunikation und IT e.V., Bonn 4. Assessment Point (Proprietary) Limited, Johannesburg 1.125. 100.00 100 ZAR (3,192) (6) ZAR e) 5. Atrada GmbH, Nuremberg 100.00 150,000 EUR 3,220 (2,210) EUR e) 6. Atrada Trading Network Limited, Manchester 1.5. 100.00 1 GBP 0 0 GBP e) 7. BENOCS GmbH, Bonn 1.327. 100.00 25,000 EUR 94 (765) EUR e) 8. Benocs, Inc., Wilmington, DE 1.7. 100.00 100 USD - - USD 9. CA INTERNET d.o.o., Zagreb 1.129. 100.00 20,000 HRK 228 11 HRK e) 10. CBS GmbH, Cologne 1.19. 100.00 838,710 EUR 18,055 0 EUR a) e) 11. CE Colo Czech, s.r.o., Prague 1.232. 100.00 711,991,857 CZK 854,466 88,237 CZK e) 12. COMBIS - IT Usluge d.o.o., Belgrade 1.14. 100.00 49,136 RSD (112,300) (9,378) EUR e) 13. COMBIS d.o.o. Sarajevo, Sarajevo 1.14. 100.00 2,000 BAM 5,297 969 BAM e) 14. -

Deutsche Telekom Services Europe Czech Republic Company Presentation OVERVIEW

Deutsche telekom services Europe Czech republic Company presentation OVERVIEW 01 Deutsche Telekom Group 02 Deutsche Telekom Services Europe 03 Deutsche Telekom Services Europe Czech Republic: overview 04 Deutsche Telekom Services Europe Czech Republic: our Teams 2 DEUTSCHE TELEKOM PROFILE German telecommunication company Headquarters in Bonn By revenue the largest telecommunications provider in Europe – 73 bn. € (2016) Formed in 1996 - the former state-owned monopoly Deutsche Bundespost was privatized Active in 36 countries worldwide More than 218.000 employees DEUTSCHE TELEKOM figures Customers & Markets Facts & Figures Customers Markets Telekom in figures, 2018 Employees & responsibility Employeesworldwide: 215,675 178.4 mnmobile customers Presentin > 50 countries Revenue € 75.7 bn 5,713 trainees and cooperative 27.9 mnfixed-network lines/ Germany, Europe and the USA: Adjusted EBITDA € 23.3 bn degree students in Germany 20.2 mnbroadband lines with own infrastructure Free Cash-Flow € 6.2 bn Pioneer of social issues Approx. 8.2 m TV customers T-Systems: global presence& (climate protection, data privacy, alliances via partners diversity, etc.) Source: DT 2018 annual report 4 Company presentation OVERVIEW 01 Deutsche Telekom Group 02 Deutsche Telekom Services Europe 03 Deutsche Telekom Services Europe Czech Republic: overview 04 Deutsche Telekom Services Europe Czech Republic: our Teams 5 Where does dtse stand in the deutsche telekom group? operating model Future target operating Headquarters give an explicit Group model -

Prepared for Upload GCD Wls Networks

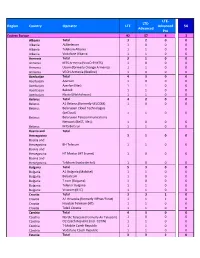

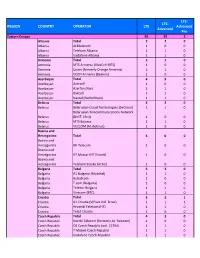

LTE‐ LTE‐ Region Country Operator LTE Advanced 5G Advanced Pro Eastern Europe 92 57 4 3 Albania Total 32 0 0 Albania ALBtelecom 10 0 0 Albania Telekom Albania 11 0 0 Albania Vodafone Albania 11 0 0 Armenia Total 31 0 0 Armenia MTS Armenia (VivaCell‐MTS) 10 0 0 Armenia Ucom (formerly Orange Armenia) 11 0 0 Armenia VEON Armenia (Beeline) 10 0 0 Azerbaijan Total 43 0 0 Azerbaijan Azercell 10 0 0 Azerbaijan Azerfon (Nar) 11 0 0 Azerbaijan Bakcell 11 0 0 Azerbaijan Naxtel (Nakhchivan) 11 0 0 Belarus Total 42 0 0 Belarus A1 Belarus (formerly VELCOM) 10 0 0 Belarus Belarusian Cloud Technologies (beCloud) 11 0 0 Belarus Belarusian Telecommunications Network (BeST, life:)) 10 0 0 Belarus MTS Belarus 11 0 0 Bosnia and Total Herzegovina 31 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina BH Telecom 11 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina HT Mostar (HT Eronet) 10 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina Telekom Srpske (m:tel) 10 0 0 Bulgaria Total 53 0 0 Bulgaria A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel) 11 0 0 Bulgaria Bulsatcom 10 0 0 Bulgaria T.com (Bulgaria) 10 0 0 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria 11 0 0 Bulgaria Vivacom (BTC) 11 0 0 Croatia Total 33 1 0 Croatia A1 Hrvatska (formerly VIPnet/B.net) 11 1 0 Croatia Hrvatski Telekom (HT) 11 0 0 Croatia Tele2 Croatia 11 0 0 Czechia Total 43 0 0 Czechia Nordic Telecom (formerly Air Telecom) 10 0 0 Czechia O2 Czech Republic (incl. CETIN) 11 0 0 Czechia T‐Mobile Czech Republic 11 0 0 Czechia Vodafone Czech Republic 11 0 0 Estonia Total 33 2 0 Estonia Elisa Eesti (incl. -

Ready for Upload GCD Wls Networks

LTE‐ LTE‐ REGION COUNTRY OPERATOR LTE Advanced Advanced Pro Eastern Europe 92 55 2 Albania Total 320 Albania ALBtelecom 100 Albania Telekom Albania 110 Albania Vodafone Albania 110 Armenia Total 310 Armenia MTS Armenia (VivaCell‐MTS) 100 Armenia Ucom (formerly Orange Armenia) 110 Armenia VEON Armenia (Beeline) 100 Azerbaijan Total 430 Azerbaijan Azercell 100 Azerbaijan Azerfon (Nar) 110 Azerbaijan Bakcell 110 Azerbaijan Naxtel (Nakhchivan) 110 Belarus Total 420 Belarus Belarusian Cloud Technologies (beCloud) 110 Belarusian Telecommunications Network Belarus (BeST, life:)) 100 Belarus MTS Belarus 110 Belarus VELCOM (A1 Belarus) 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina Total 300 Bosnia and Herzegovina BH Telecom 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina HT Mostar (HT Eronet) 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina Telekom Srpske (m:tel) 100 Bulgaria Total 530 Bulgaria A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel) 110 Bulgaria Bulsatcom 100 Bulgaria T.com (Bulgaria) 100 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria 110 Bulgaria Vivacom (BTC) 110 Croatia Total 321 Croatia A1 Croatia (VIPnet incl. B.net) 111 Croatia Hrvatski Telekom (HT) 110 Croatia Tele2 Croatia 100 Czech Republic Total 430 Czech Republic Nordic Telecom (formerly Air Telecom) 100 Czech Republic O2 Czech Republic (incl. CETIN) 110 Czech Republic T‐Mobile Czech Republic 110 Czech Republic Vodafone Czech Republic 110 Estonia Total 330 Estonia Elisa Eesti (incl. Starman) 110 Estonia Tele2 Eesti 110 Telia Eesti (formerly Eesti Telekom, EMT, Estonia Elion) 110 Georgia Total 630 Georgia A‐Mobile (Abkhazia) 100 Georgia Aquafon GSM (Abkhazia) 110 Georgia MagtiCom -

Further Relevant Information Related to Deutsche Telekom Footprint in Detail

FURTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION RELATED TO DEUTSCHE TELEKOM FOOTPRINT IN DETAIL Criteria Name of the Group Telekom in T Mobile US OTE Magyar Hrvatski T-Mobile Czech Slovak Telekom Germany Telekom Telekom Republic resident Hellenic entities Telecommunications organization S.A. Primary Fixed- Fixed-network/ Fixed-network/ Fixed and mobile Phone, Phone, Converged Provider of activities network/broadb broadband, mobile broadband, telephony, broadband, broadband, telecommunicatio mobile and, mobile communications, mobile broadband services, TV and IT TV and IT ns services, TV, communication communications, Internet, IPTV communications pay television and Magyar Hrvatski comprehensive and wired Internet, IPTV products and , Internet, IPTV integrated ICT Telekom Telekom ICT solutions broadband products and services for products and solutions Company Company T-Mobile Czech internet services for consumers, ICT services for OTE Group Profile Profile Republic through optical consumers consumers, ICT solutions for Company Profile Company Profile and metallic T-Mobile US solutions business and networks Company Deutsche corporate Slovak Telekom Profile) Company Telekom Group customers Profile Company Profile Telekom in Germany Company Profile 2 IN DETAIL Group Telekom in T Mobile US OTE Magyar Hrvatski T-Mobile Slovak Germany Telekom Telekom Czech Telekom Republic Average Number of 224,000 (p.3a) 89,032 (p.8e) 65,015 (p. 185a) 16,441(p. 185a) 7,349 (p. 185a) 4,957(p. 185a) 3,272 (p. 3,336 (p. 185a) Employees 185a) Net Revenue in 100,999 25,671 (p.185, 61,208 (p. 185) 3,878 (p. 185) 1,914 (p. 185) 989 (p.185) 1,072 (p.185) 773 (p. 185) Mio. EURa) 237f) Revenue in % 100 25 61 4 2 1 1 1 Profit (Loss)/ before 12,800 (p. -

SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT Contents T-Mobile C Zech Republic A.S

2019 republic a.s. czech T-mobile summary annual reporT T-mobile czech republic a.s. conTenT s CONTENTS 2 SUMMARY ANNUAL reporT conTenTs T-mobile c zech republic a.s. Foreword 2 report of the board of Directors on business activities and assets 6 report on relationships 22 Financial statements according to the international Financial reporting standards 52 consolidated Financial statements according to the international Financial reporting standards 92 independent auditor’s report 132 SUMMARY ANNUAL reporT 1 T-mobile czech republic a.s. inTRODucTion INTRO- DUCTION builiDinG FULLY DiGiTal CZECHIA Digitisation is one of the main challenges that the czech republic is facing. i am very honoured that T-mobile czech republic has played a very important role in this transformation process and that we can take part in the transformation into a truly digital society. With its expertise, technologies, services and investments, T-mobile has contributed and can continue to contribute to the building of a fully digital czech republic. i am aware of the great responsibility that comes with this, but we are prepared to further increase our participation in the digital transformation of the entire czech republic in the coming years. 2 SUMMARY ANNUAL reporT inTRODucTion T-mobile c zech republic a.s. 3 SUMMARY ANNUAL reporT 3 T-mobile czech republic a.s. inTRODucTion The task that lies before us could not be achieved without massive investments in the development of the existing technologies, rollout of the fibre-optic network, introduction of new services and making modern communication tools available to the entire population. -

Deutsche Telekom AG

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 1, 2007 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Form 20-F È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2006 Commission file number 001-14540 Deutsche Telekom AG (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Federal Republic of Germany (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 140, 53113 Bonn, Germany (Address of Registrant’s Principal Executive Offices) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares, each representing New York Stock Exchange one Ordinary Share Ordinary Shares, no par value New York Stock Exchange* Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: NONE (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report: Ordinary Shares, no par value: 4,361,119,250 (as of December 31, 2006) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes È No ‘ If this report is an annual or transition report, indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. -

5G Observatory Quarterly Report 12 up to June 2021

5G Observatory Quarterly Report 12 Up to June 2021 A study prepared for the European Commission DG Communications Networks, Content & Technology by: 5G Observatory – Quarterly Report #12 This study was carried out for the European Commission by IDATE DigiWorld Authors: Frédéric PUJOL, Carole MANERO, Basile CARLE and Santiago REMIS 90013 – July 2021 Internal identification Contract number: LC-00838363 SMART number 2019/009 DISCLAIMER By the European Commission, Directorate-General of Communications Networks, Content & Technology. The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. © European Union, 2020. All rights reserved. Certain parts are licenced under conditions to the EU. www.idate.org © IDATE DigiWorld 2021 – p. 2 5G Observatory – Quarterly report #12 Contents 1. Executive summary ............................................................................................................. 7 Status of 5G deployment in Europe and assessment against the 5G Action Plan..................................................... 7 5G deployment outside Europe .............................................................................................................................. 9 Framework conditions -

2017 ICT Principle Implementation Report

Principles for the Safer Use of Connected Devices and Online Services by Children and Young People in the EU Implementation Questionnaire July 2017 1 Principles for the Safer Use of Connected Devices and Online Services by Children and Young People in the EU Introduction Notes/instructions on completing this template • Please complete all sections and all questions as far as possible • Where a question or section is not applicable, please mark as N/A • Where is overlap – or no change – to information previously submitted in company statement of commitments, please simply enter “refer to self-statement” • URLs or screenshots (with links) are particularly useful in illustrating individual points • Please add any additional information/data relevant to the submission at the end of the appropriate Principle • In case you have different solutions in EU markets, please provide examples in the relevant sections 1. Name of the company on whose behalf this submission is made: Deutsche Telekom AG Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 140 53113 Bonn Germany 2. Country or primary markets where products/services are offered (in EU) to which this submission applies. Please indicate all EU-markets in which your company operates In January 2013, Deutsche Telekom has committed to a set of 25 measures to further increase child online safety.1 These apply to every subsidiary company of Deutsche Telekom Group: § T-Mobile Austria GmbH, Austria § Hrvatski Telekom d.d., Croatia § T-Mobile Czech Republic, a.s., Czech Republic § Telekom Deutschland GmbH, Germany § COSMOTE, Greece § Magyar Telekom Nyrt., Hungary § T-Mobile Netherlands B.V., Netherlands § T-Mobile Polska S.A., Poland § Telekom Romania, Romania § Slovak Telekom, a.s., Slovakia In the past four years, great progress has been made in each subsidiary company. -

Volte Launches

VoLTE launches Country Operator VoLTE Status VoLTE Launched Korea, South KT VoLTE Launched 01-Dec-12 Korea, South LG Uplus VoLTE Launched 01-Dec-12 Korea, South SK Telecom VoLTE Launched 01-Dec-12 Hong Kong SmarTone VoLTE Launched 01-May-14 Singapore M1 VoLTE Launched 01-May-14 United States of America Verizon Wireless VoLTE Launched 01-May-14 Japan NTT DOCOMO VoLTE Launched 01-Jun-14 United States of America AT&T VoLTE Launched 01-Jun-14 Hong Kong CSL (HKT) VoLTE Launched 01-Jul-14 United Arab Emirates Du VoLTE Launched 04-Aug-14 United States of America T-Mobile (Deutsche Telekom) VoLTE Launched 01-Sep-14 Singapore SingTel VoLTE Launched 27-Sep-14 Japan au (KDDI) VoLTE Launched 01-Dec-14 Japan SoftBank VoLTE Launched 01-Dec-14 Canada Rogers VoLTE Launched 01-Mar-15 Hong Kong 3 (CK Hutchison) VoLTE Launched 01-Mar-15 Germany O2 (Telefónica) VoLTE Launched 01-Apr-15 Singapore StarHub VoLTE Launched 01-Apr-15 South Africa Vodacom VoLTE Launched 01-Apr-15 Czech Republic T-Mobile (Deutsche Telekom) VoLTE Launched 01-May-15 Germany Vodafone VoLTE Launched 01-May-15 Taiwan Ambit Microsystems (Hon Hai VoLTE Launched 15-May-15 Precision Industry) Taiwan Asia Pacific Telecom VoLTE Launched 15-May-15 Kuwait Viva (STC) VoLTE Launched 01-Jun-15 Liechtenstein Swisscom VoLTE Launched 01-Jun-15 Switzerland Swisscom VoLTE Launched 01-Jun-15 Cambodia SEATEL (Southeast Asia Telecom) VoLTE Launched 01-Jul-15 Italy Vodafone VoLTE Launched 01-Jul-15 Spain Vodafone VoLTE Launched 01-Jul-15 China China Mobile VoLTE Launched 01-Aug-15 Russian Federation Beeline -

Interim Group Report 2

JANUARY 1 TO JUNE 30, 2015 INTERIM GROUP REPORT 2 SElEcted financial data Of ThE Group millions of € Q2 2015 Q2 2014 Change % H1 2015 H1 2014 Change % FY 2014 REVENUE AND EARNINGS Net revenue 17,428 15,114 15.3 % 34,270 30,008 14.2 % 62,658 Of which: domestic % 35.8 40.4 36.4 40.9 39.9 Of which: international % 64.2 59.6 63.6 59.1 60.1 Profit from operations (EBIT) 1,806 1,776 1.7 % 3,272 4,918 (33.5) % 7,247 Net profit (loss) 712 711 0.1 % 1,499 2,528 (40.7) % 2,924 Net profit (loss) (adjusted for special factors) 1,078 636 69.5 % 2,114 1,223 72.9 % 2,422 EBITDA 4,534 4,417 2.6 % 8,694 10,055 (13.5) % 17,821 EBITDA (adjusted for special factors) 5,026 4,429 13.5 % 9,600 8,550 12.3 % 17,569 EBITDA margin (adjusted for special factors) % 28.8 29.3 28.0 28.5 28.0 Earnings per share basic/diluted € 0.16 0.16 0.0 % 0.33 0.57 (42.1) % 0.65 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION Total assets 134,978 118,028 14.4 % 129,360 Shareholders’ equity 35,961 32,501 10.6 % 34,066 Equity ratio % 26.6 27.5 26.3 Net debt 48,835 41,385 18.0 % 42,500 CASH FLOWS Net cash from operating activities 3,871 3,187 21.5 % 7,179 6,149 16.8 % 13,393 Cash capex (4,330) (3,946) (9.7) % (8,759) (6,143) (42.6) % (11,844) Free cash flow (before dividend payments and spectrum investment) 1,375 1,049 31.1 % 2,240 2,032 10.2 % 4,140 Net cash used in investing activities (3,824) (4,688) 18.4 % (6,761) (5,036) (34.3) % (10,761) Net cash used in financing activities (394) (1,844) 78.6 % (3,530) (4,750) 25.7 % (3,434) NUMBER OF FIXED-NETWORK AND MOBILE CUSTOMERS millions Change Change June 30, 2015/ June 30, 2015/ Dec. -

List of 4G Partners in Countries Around the World

List of 4G partners in countries around the world Country Network ALBANIA AMC (Albanian Mobile) ANTIGUA & Cable & Wireless Caribbean Cellular (Antigua) BARBUDA Limi ARGENTINA Telecom Personal AUSTRALIA Optus Communications AUSTRALIA Telstra AUSTRIA T-Mobile Austria AZERBAIJAN Bakcell BAHRAIN Batelco BELGIUM Mobistar BULGARIA Globul - Cosmo Bulgaria CANADA Telus CANADA Bell Mobility CANADA Rogers Communications CAYMAN ISLANDS Cable & Wireless (Cayman Islands) (LIME) CHINA China Mobile (old) CHINA China Unicom CROATIA T-Mobile Croatia CYPRUS MTN Cyprus CZECH REPUBLIC T-Mobile Czech DENMARK Telia Mobile DENMARK Tele Danmark Mobil DENMARK Telenor A/S Denmark DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Orange Dominican Republic EGYPT MobiNil ESTONIA Estonian Mob Tel ESTONIA Tele2 Estonia FINLAND TeliaSonera Finland Oyj FRANCE Orange France FRANCE Bouygues Telecom GERMANY Telefonica Germany GERMANY T-Mobile Germany GREECE Wind Greece GREECE Cosmote Mobile Telecom GUERNSEY C&W Guernsey (GRN) HONG KONG SmartTone HONG KONG CSL HUNGARY Pannon GSM HUNGARY T-Mobile Hungary ICELAND Vodafone Iceland INDIA - Andhra Pradesh Airtel Bharti [Andhra Pradesh] INDJH - 40449 INDIA - Chennai Airtel Bharti [Chennai] INDSC - 40440 INDIA - Delhi Airtel Bharti [Delhi] INDAT - 40410 INDIA - Haryana Airtel Bharti [Haryana] INDA5 - 40496 INDIA - Himachal Pradesh Airtel Bharti [Himachal Pradesh] INDBL - 40403 INDIA - Karnataka Airtel Bharti [Karnataka] INDJB - 40445 Country Network INDIA - Kerala Airtel Bharti [Kerala] INDA7 - 40495 INDIA - Kolkata Airtel Bharti [Calcutta] INDMT - 40431 INDIA