Sourcebook in Forensic Serology, Immunology, and Biochemistry Presence of Blood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleiotropic Effects of Antithrombin Strand 1C Substitution Mutations

Pleiotropic effects of antithrombin strand 1C substitution mutations. D A Lane, … , E Thompson, G Sas J Clin Invest. 1992;90(6):2422-2433. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI116133. Research Article Six different substitution mutations were identified in four different amino acid residues of antithrombin strand 1C and the polypeptide leading into strand 4B (F402S, F402C, F402L, A404T, N405K, and P407T), and are responsible for functional antithrombin deficiency in seven independently ascertained kindreds (Rosny, Torino, Maisons-Laffitte, Paris 3, La Rochelle, Budapest 5, and Oslo) affected by venous thromboembolic disease. In all seven families, variant antithrombins with heparin-binding abnormalities were detected by crossed immunoelectrophoresis, and in six of the kindreds there was a reduced antigen concentration of plasma antithrombin. Two of the variant antithrombins, Rosny and Torino, were purified by heparin-Sepharose and immunoaffinity chromatography, and shown to have greatly reduced heparin cofactor and progressive inhibitor activities in vitro. The defective interactions of these mutants with thrombin may result from proximity of s1C to the reactive site, while reduced circulating levels may be related to s1C proximity to highly conserved internal beta strands, which contain elements proposed to influence serpin turnover and intracellular degradation. In contrast, s1C is spatially distant to the positively charged surface which forms the heparin binding site of antithrombin; altered heparin binding properties of s1C variants may therefore reflect conformational linkage between the reactive site and heparin binding regions of the molecule. This work demonstrates that point mutations in and immediately adjacent to strand 1C have multiple, or pleiotropic, […] Find the latest version: https://jci.me/116133/pdf Pleiotropic Effects of Antithrombin Strand 1C Substitution Mutations David A. -

Pre-Antibiotic Therapy of Syphilis Charles T

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics Faculty Publications Genetics 2016 Pre-Antibiotic Therapy of Syphilis Charles T. Ambrose University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/microbio_facpub Part of the Medical Immunology Commons Repository Citation Ambrose, Charles T., "Pre-Antibiotic Therapy of Syphilis" (2016). Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics Faculty Publications. 83. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/microbio_facpub/83 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pre-Antibiotic Therapy of Syphilis Notes/Citation Information Published in NESSA Journal of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, v. 1, issue 1, p. 1-20. © 2016 C.T. Ambrose This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/microbio_facpub/83 Journal of Infectious Diseases and Immunology Volume 1| Issue 1 Review Article Open Access PRE-ANTIBIOTICTHERAPY OF SYPHILIS C.T. Ambrose, M.D1* 1Department of Microbiology, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky *Corresponding author: C.T. Ambrose, M.D, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky Department of Microbiology, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: C.T. -

Technical Note: Colorimetric Protein Assays Assays for Determining Protein Concentration

Technical Note: Colorimetric Protein Assays Assays for Determining Protein Concentration Contents speed. No colorimetric assay is as simple and quick as direct UV measurements at 280 nm for Introduction ....................................................... 1 the determination of protein concentration. Assay Choice ..................................................... 1 However measurements at 280 nm rely on the Buffer Composition ........................................ 1 protein containing aromatic amino acids such as Sample Composition ...................................... 2 tyrosine (Y), phenylalanine (F), and, or tryptophan Standard Selection ......................................... 2 (W). Not all proteins contain these amino acids, Assays ................................................................ 2 and the relative proportions of theses amino acids Biuret, BCA, and Lowry Assays ..................... 3 differ between proteins. Furthermore, if nucleic Bradford Assay............................................... 3 acids are present in the sample, they would also Troubleshooting ............................................. 4 absorb light at 280 nm, further compromising FAQ’s .................................................................. 5 accuracy. Therefore, the sensitivity achieved Bibliography ...................................................... 5 without prior knowledge of the protein of interest’s Contact Us ......................................................... 6 absorbance maxima (λmax) and attenuation coefficient -

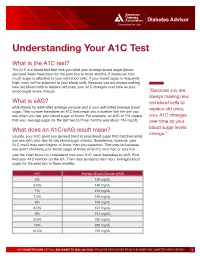

Understanding Your A1C Test

Diabetes Advisor Understanding Your A1C Test What is the A1C test? The A1C is a blood test that tells you what your average blood sugar (blood glucose) levels have been for the past two to three months. It measures how much sugar is attached to your red blood cells. If your blood sugar is frequently high, more will be attached to your blood cells. Because you are always making new red blood cells to replace old ones, your A1C changes over time as your blood sugar levels change. “Because you are always making new What is eAG? red blood cells to eAG stands for estimated average glucose and is your estimated average blood replace old ones, sugar. This number translates an A1C test result into a number like the one you see when you test your blood sugar at home. For example, an A1C of 7% means your A1C changes that your average sugar for the last two to three months was about 154 mg/dL. over time as your What does an A1C/eAG result mean? blood sugar levels change.” Usually, your A1C gives you general trend in your blood sugar that matches what you see with your day-to-day blood sugar checks. Sometimes, however, your A1C result may seem higher or lower than you expected. That may be because you aren’t checking your blood sugar at times when it’s very high or very low. Use the chart below to understand how your A1C result translates to eAG. First find your A1C number on the left. -

Serological (Antibody) Testing for Covid-19

SEROLOGICAL (ANTIBODY) TESTING FOR COVID-19 Serological tests detect antibodies in the blood People in the early stages of COVID-19 might generated as part of the immune response test antibody negative despite being highly to a specific infection, such as infection with infectious. Additionally, some tests might give a SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. false positive result because of past or present Antibody tests are different from tests such as infection with other types of coronaviruses. polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antigen False positive results are also more likely tests which detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus. when the percentage of the population with Many new serological tests for COVID-19 have the disease is low. The Idaho Division of Public been developed and have an emergency use Health discourages persons who have a positive authorization (EUA) from the U.S. Food and serology test from relaxing the precautions such Drug Administration (FDA). Only antibody tests as social distancing that are recommended for that have an FDA EUA should be used. The all Idahoans to prevent spread of coronavirus, Idaho Division of Public Health discourages and strongly discourages employers form the use of unauthorized serology-based assays relaxing the employee protections for an for diagnosis of COVID-19 or determining if employee solely based upon a positive serology someone is currently infected or had a prior test. infection. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 (the Serological tests are not recommended for virus that causes COVID-19) infection is not COVID-19 diagnosis in most situations because well understood. -

Jaundice Protocol

fighting childhood liver disease Jaundice Protocol Early identification and referral of liver disease in infants fighting childhood liver disease 36 Great Charles Street Birmingham B3 3JY Telephone: 0121 212 3839 yellowalert.org childliverdisease.org [email protected] Registered charity number 1067331 (England & Wales); SC044387 (Scotland) The following organisations endorse the Yellow Alert Campaign and are listed in alphabetical order. 23957 CLDF Jaundice Protocol.indd 1 03/08/2015 18:25:24 23957 3 August 2015 6:25 PM Proof 1 1 INTRODUCTION This protocol forms part of Children’s Liver Disease Foundation’s (CLDF) Yellow Alert Campaign and is written to provide general guidelines on the early identification of liver disease in infants and their referral, where appropriate. Materials available in CLDF’s Yellow Alert Campaign CLDF provides the following materials as part of this campaign: • Yellow Alert Jaundice Protocol for community healthcare professionals • Yellow Alert stool colour book mark for quick and easy reference • Parents’ leaflet entitled “Jaundice in the new born baby”. CLDF can provide multiple copies to accompany an antenatal programme or for display in clinics • Yellow Alert poster highlighting the Yellow Alert message and also showing the stool chart 2 GENERAL AWARENESS AND TRAINING The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has published a clinical guideline on neonatal jaundice which provides guidance on the recognition, assessment and treatment of neonatal jaundice in babies from birth to 28 days. Neonatal Jaundice Clinical Guideline guidance.nice.org.uk cg98 For more information go to nice.org.uk/cg98 • Jaundice Community healthcare professionals should be aware that there are many causes for jaundice in infants and know how to tell them apart: • Physiological jaundice • Breast milk jaundice • Jaundice caused by liver disease • Jaundice from other causes, e.g. -

Journal of Blood Group Serology and Molecular Genetics Volume 34, Number 1, 2018 CONTENTS

Journal of Blood Group Serology and Molecular Genetics VOLUME 34, N UMBER 1, 2018 This issue of Immunohematology is supported by a contribution from Grifols Diagnostics Solutions, Inc. Dedicated to advancement and education in molecular and serologic immunohematology Immunohematology Journal of Blood Group Serology and Molecular Genetics Volume 34, Number 1, 2018 CONTENTS S EROLOGIC M ETHOD R EVIEW 1 Warm autoadsorption using ZZAP F.M. Tsimba-Chitsva, A. Caballero, and B. Svatora R EVIEW 4 Proceedings from the International Society of Blood Transfusion Working Party on Immunohaematology Workshop on the Clinical Significance of Red Blood Cell Alloantibodies, Friday, September 2, 2016, Dubai A brief overview of clinical significance of blood group antibodies M.J. Gandhi, D.M. Strong, B.I. Whitaker, and E. Petrisli C A S E R EPORT 7 Management of pregnancy sensitized with anti-Inb with monocyte monolayer assay and maternal blood donation R. Shree, K.K. Ma, L.S. Er and M. Delaney R EVIEW 11 Proceedings from the International Society of Blood Transfusion Working Party on Immunohaematology Workshop on the Clinical Significance of Red Blood Cell Alloantibodies, Friday, September 2, 2016, Dubai A review of in vitro methods to predict the clinical significance of red blood cell alloantibodies S.J. Nance S EROLOGIC M ETHOD R EVIEW 16 Recovery of autologous sickle cells by hypotonic wash E. Wilson, K. Kezeor, and M. Crosby TO THE E DITOR 19 The devil is in the details: retention of recipient group A type 5 years after a successful allogeneic bone marrow transplant from a group O donor L.L.W. -

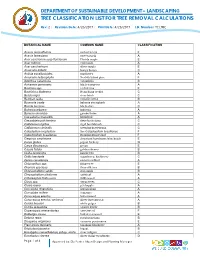

Tree Classification List for Tree Removal Calculations

DEPARTMENT OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT – LANDSCAPING TREE CLASSIFICATION LIST FOR TREE REMOVAL CALCULATIONS Rev: 2 | Revision Date: 4/26/2017 | Print Date: 4/26/2017 I.D. Number: TCLTRC BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME CLASSIFICATION Acacia auriculiformis earleaf acacia F Acacia farnesiana sweet acacia A Acer saccharum susp floridanum Florida maple E Acer rubrum red maple A Acer saccharinum silver maple E Araucaria bidwilli bunya bunya C Ardisia escallonioides marlberry A Araucaria heterophylla Norfolk Island pine F Averrhoa carambola carambola B Avicennia germinans black mangrove A Bauhinia spp. orchid tree E Bauhinia x blakeana Hong Kong orchid C Betula nigra river birch C Bombax ceiba red silk cotton B Bourreria ovata bahama strongbark A Bucida buceras black olive C Bulnesia arborea bulnesia A Bursera simaruba gumbo limbo A Caesalpinia granadillo bridalveil A Caesalpinia pulcherrima dwarf poinciana C Callistemon rigidus rigid bottlebrush C Callistemon viminalis weeping bottlebrush C Calophyllum inophyllum See Calophyullum brasiliense F Calophyullum brasiliense Brazilian Beautyleaf F Carpinus caroliniana American hornbeam; blue beech E Carya glabra pignut hickory D Carya illinoinensis pecan E Cassia fistula golden shower B Ceiba pentandra kapok tree B Celtis laevigata sugarberry; hackberry C Cercis canadensis eastern redbud A Chionanthus spp. fringe tree E Chorisia speciosa floss-silk tree B Chrysophyllum cainito star-apple B Chrysophyllum oliviforme satinleaf A Citharexylum fruticosum fiddlewood A Citrus spp. citrus trees C Clusia rosea pitchapple A Coccoloba diversifolia pigeon plum A Coccoloba uvifera seagrape A Conocarpus erectus buttonwood A Conocarpus erectus ‘sericeus’ silver buttonwood A Cordia bossieri white geiger B Cordia sebestena orange geiger B Cupaniopsis anacardiodes carrotwood F Dalbergia sissoo Indian rosewood E Delonix regia royal poinciana B Diospyros virginiana common persimmon E Eleocarpus decipens Japanese blueberry A Eriobotrya japonica loquat B Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. -

Phenolphthalein, 0.5% in 50% Ethanol Safety Data Sheet According to Federal Register / Vol

Phenolphthalein, 0.5% in 50% Ethanol Safety Data Sheet according to Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 58 / Monday, March 26, 2012 / Rules and Regulations Issue date: 12/17/2013 Revision date: 07/21/2020 Supersedes: 01/23/2018 Version: 1.5 SECTION 1: Identification 1.1. Identification Product form : Mixtures Product name : Phenolphthalein, 0.5% in 50% Ethanol Product code : LC18200 1.2. Recommended use and restrictions on use Use of the substance/mixture : For laboratory and manufacturing use only. Recommended use : Laboratory chemicals Restrictions on use : Not for food, drug or household use 1.3. Supplier LabChem, Inc. 1010 Jackson's Pointe Ct. Zelienople, PA 16063 - USA T 412-826-5230 - F 724-473-0647 [email protected] - www.labchem.com 1.4. Emergency telephone number Emergency number : CHEMTREC: 1-800-424-9300 or +1-703-741-5970 SECTION 2: Hazard(s) identification 2.1. Classification of the substance or mixture GHS US classification Flammable liquids Category 3 H226 Flammable liquid and vapor Carcinogenicity Category 1A H350 May cause cancer Reproductive toxicity Category 2 H361 Suspected of damaging the unborn child. (oral) Specific target organ toxicity (single exposure) Category 1 H370 Causes damage to organs (central nervous system, optic nerve) (oral, Dermal) Full text of H statements : see section 16 2.2. GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements GHS US labeling Hazard pictograms (GHS US) : Signal word (GHS US) : Danger Hazard statements (GHS US) : H226 - Flammable liquid and vapor H350 - May cause cancer H361 - Suspected of damaging the unborn child. (oral) H370 - Causes damage to organs (central nervous system, optic nerve) (oral, Dermal) Precautionary statements (GHS US) : P201 - Obtain special instructions before use. -

The Action of the Phosphatases of Human Brain on Lipid Phosphate Esters by K

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.19.1.12 on 1 February 1956. Downloaded from J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 1956, 19, 12 THE ACTION OF THE PHOSPHATASES OF HUMAN BRAIN ON LIPID PHOSPHATE ESTERS BY K. P. STRICKLAND*, R. H. S. THOMPSON, and G. R. WEBSTER From the Department of Chemical Pathology, Guy's Hospital Medical School, London, Much work, using both histochemical and therefore to study the action of the phosphatases in standard biochemical techniques, has been carried human brain on the " lipid phosphate esters out on the phosphatases of peripheral nerve. It is i.e., on the various monophosphate esters that occur known that this tissue contains both alkaline in the sphingomyelins, cephalins, and lecithins. In (Landow, Kabat, and Newman, 1942) and acid addition to ox- and 3-glycerophosphate we have phosphatases (Wolf, Kabat, and Newman, 1943), therefore used phosphoryl choline, phosphoryl and the changes in the levels of these enzymes in ethanolamine, phosphoryl serine, and inositol nerves undergoing Wallerian degeneration following monophosphate as substrates for the phospho- transection have been studied by several groups of monoesterases, and have measured their rates guest. Protected by copyright. of investigators (see Hollinger, Rossiter, and Upmalis, hydrolysis by brain preparations over the pH range 1952). 4*5 to 100. Phosphatase activity in brain was first demon- Plimmer and Burch (1937) had earlier reported strated by Kay (1928), and in 1934 Edlbacher, that phosphoryl choline and phosphoryl ethanol- Goldschmidt, and Schiiippi, using ox brain, showed amine are hydrolysed by the phosphatases of bone, that both acid and alkaline phosphatases are kidney, and intestine, but thepH at which the hydro- present in this tissue. -

Photography of Bloodstains Visualized by Luminol

J Forensic Sci, Oct. 1973, Vol. 18, No. 4 R. A. Zweidinger, ~ Ph.D., L. T. Lytle, 2 M.S., and C, G. Pitt, ~ Ph.D. Photography of Bloodstains Visualized by Luminol The chemical tests for blood currently in use depend upon the detection of hemoglobin or one of its derivatives [1]. Hemoglobin has several properties which make it suitable for this purpose. The most important, due to its sensitivity, is the peroxidase activity of hemo- globin heme which forms the basis of the benzidine, leuco-malachite green, phenol- phthalein, and luminol tests for blood. The luminol test, which is based on the visual observation of chemiluminescence, is particularly useful forensically because of its sensi- tivity; as a spray reagent, it also permits the detection and observation of the shape and fine structure of the bloodstains which would otherwise be invisible to the naked eye [2-51. While it is obviously desirable to be able to obtain a permanent record of luminol visualized bloodstains for court evidence, photography has previously been of little value because of the low intensity and short duration of the luminescence. However, recent advances in high speed film have justified a reappraisal, and here we describe experimental conditions which have been successfully employed to obtain a photographic record. Modifications of the Luminol Test Prior to photographic studies it was necessary to determine the optimum experimental conditions of the luminol test, in terms of intensity and duration of light emission. The standard luminol spray reagent [1] was taken as a point of reference for evaluating other formulations. -

Comparison of Histopathology, Immunofluorescence, and Serology

Global Dermatology Cae Report ISSN: 2056-7863 Comparison of histopathology, immunofluorescence, and serology for the diagnosis of autoimmune bullous disorders: an update Seline Ali E1, Seline Lauren N1, Sokumbi Olayemi1* and Motaparthi Kiran2,3 1Department of Dermatology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA 2Dermatopathology, Miraca Life Sciences, USA 3Department of Dermatology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA Introduction In an ELISA, the target antigen of interest (such as the NC16a domain of BP180) is immobilized by physical adsorption or by The diagnosis of autoimmune bullous disorders (AIBDs) relies on antibody capture. When antibody capture is utilized, this is referred to several different diagnostic methods. These include histopathology, as “sandwich ELISA” because the target antigen is bound between the direct immunofluorescence (DIF), indirect immunofluorescence immobilizing antibody and the primary antibody. Primary antibodies (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and are present in the patient’s serum. Enzyme-linked secondary antibodies immunoblotting. When faced with a presumptive AIBD, the are then added which bind the Fc region of primary antibodies. most widely employed method for diagnosis by dermatologists is Substrate is added and converted by the enzyme into a signal. A a combination of histopathology and DIF. While DIF is still the resulting color change, fluorescence, or electrochemical signal is diagnostic method of choice for linear IgA bullous disease and IgA quantitatively measured and reported [5]. pemphigus, ELISA is a more accurate, cost-effective and less invasive method of diagnosis for several AIBDs including pemphigus vulgaris Western blot is synonymous with immunoblot. For this method, and foliaceus, based on currently available evidence [1-3].