The Strangers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

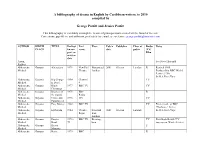

A Bibliography of Drama in English by Caribbean Writers, to 2010 Compiled By

A bibliography of drama in English by Caribbean writers, to 2010 compiled by George Parfitt and Jessica Parfitt This bibliography is inevitably incomplete. A note of principal sources used will be found at the end. Corrections, gap-fillers, and additions, preferably by e-mail, are welcome: [email protected] AUTHOR BIRTH TITLE Earliest Perf Place Pub’n Publisher Place of Radio Notes PLACE known venue date pub’n /TV/ perf. or Film written date Aaron, See Steve Hyacinth Philbert Abbensetts, Guyana Alterations 1978 New End Hampstead 2001 Oberon London R Revised 1985. Michael Theatre London Produced for BBC World Service 1980. In M.A.Four Plays Abbensetts, Guyana Big George 1994 Channel TV Michael Is Dead 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Black 1977 BBC TV TV Michael Christmas Abbensetts, Guyana Brothers of 1978 BBC R Michael the Sword Radio Abbensetts, Guyana Crime and 1976 ITV TV Michael Punishment Abbensetts, Guyana Easy Money 1982 BBC TV TV First episode of BBC Michael ‘Playhouse’ Series Abbensetts, Guyana El Dorado 1984 Theatre Stratford 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Royal East, London Abbensetts, Guyana Empire 1978 - BBC TV Birming- TV First black British T.V. Michael Road 79 ham soap opera. Wrote 2 series Abbensetts, Guyana Heavy F Michael Manners Abbensetts, Guyana Home 1975 BBC R Michael Again Radio Abbensetts, Guyana In The 1981 Hamp- London 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Mood stead Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Inner City 1975 Granada Manchest- TV Episode One of ‘Crown Michael Blues TV er Court’ Abbensetts, Guyana Little 1994 Channel TV 4-part drama Michael Napoleons 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Outlaw 1983 Arts Leicester Michael Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Roadrunner 1977 ITV TV First episode of ‘ITV Michael Playhouse’ series Abbensetts, Guyana Royston’s 1978 BBC TV Birming- 1988 Heinemann London TV Episode 4, Series 1 of Michael Day ham Empire Road. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE StrongBack Productions with Tara Theatre present: Chigger Foot Boys A World Premiere reveals untold stories of young Jamaican soldiers as the world continues to reflect upon the four years of the First World War centenary Written by Patricia Cumper | Directed by Irina Brown Tara Theatre, 22 Feb – 11 March 2017 PRESS NIGHT: Friday 24th February 2017, 7.30pm Patricia Cumper, renowned playwright and former Artistic Director of Talawa Theatre, draws inspiration from personal and historical stories in her latest play, set in a rum bar by the docks in Kingston, Jamaica 1914. Oblivious of the impact that the distant war in Europe will have on them, their island and the future of the British Empire, a soldier, a hunter, a scholar and a lover are playing a game of dominoes whilst trapped by a thunderstorm. Amongst them is a young Norman Manley, future statesman and National Hero of Jamaica. In a series of flash forwards, Chigger Foot Boys delves into the fate that awaits them and many other Jamaicans who volunteered and fought on the fronts of World War One. Director Irina Brown, is a former Artistic Director of the Tron Theatre, Glasgow (1996-1999). She has directed many theatre and opera productions, that include her work at the National Theatre (multiple award winning play Further Than the Furthest Thing by Zinnie Harris), the Royal Opera House (Bird of Night by Dominique Le Gendre), the West End (Vagina Monologues), and the Royal Albert Hall (Orango at the Proms, 2015). As Artistic Director of the Natural Perspective TC, she directed Racine’s Britannicus (Wilton’s Music Hall) and Jenufa (Arcola). -

Roy Williams Has Been Quoted in the Guardian Saying: "We Only Ever Get

Comedy, drama and black Britain – An interview with Paulette Randall Eva Ulrike Pirker British theatre director Paulette Randall once said about herself and her work, "I'm not a politician, and I never set out to be one. What I do believe is that if we are in the business of theatre, of art, of creating, then that has to be at the forefront. The product, the play, has to be paramount."1 A look at her creative output, however, shows her political engagement in place – not so much in the sense of taking a proffered side, but certainly in the sense of insisting on participation in the public debate. To name just a few of her recent projects: Her 2003 production of Urban Afro Saxons at the Theatre Royal Stratford East was a timely intervention in the public debate about Britishness. The staging of James Baldwin's Blues for Mr Charlie (2004) at the Tricycle Theatre provided a thought-provoking viewing experience for a British audience in the wake of the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. For the Trycicle and Talawa Theatre Company, Randall has staged four of August Wilson's plays. Her most recent theatre project was a production of Mustapha Matura's adaptation of Chekhov's Three Sisters at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 2006.2 However, Paulette Randall also has a professional life outside the theatre, where she makes her impact on the landscape of British sitcoms as a television producer. The following interview focuses not so much on specific productions, but more generally on her views on television, Britain's theatre culture, and the representations of Britain's diverse society. -

Chigger Foot Boys Education Resource Pack

Chigger Foot Boys Education Resource Pack StrongBack Productions with Tara Arts present the world premiere Tara Theatre 22 February – 11 March Contents 1. Introduction 2. Synopsis 3. About the Playwright 4. Patricia Cumper on Chigger Foot Boys 5. About Strongback 6. About Tara Arts 7. The Cast and Creative Team - Biographies - Q & A with the cast 7. What does ‘Chigger Foot’ mean? 8. Historical Context - The Empire 9. Historical Context - World War 1 10. Norman Manley 11. Dominoes 12. Activities for the classroom 13. Research & Bibliography Introduction Chigger Foot Boys is a new ensemble play by Patricia Cumper which marks the 100th anniversary of World War One, opening at Tara Theatre in February 2017. Based on true events in the lives of Jamaicans who fought in World War One and set amid the banter of a rum bar near Kingston Harbour, four young men tell their stories of death and glory as the end of the British Empire looms. An intoxicating cocktail of love, duty, death and dominoes. This Education Resource Pack enables teachers and students to explore further the world of the play, providing imaginative exercises and activities that connect historical context across the National Curriculum at Key Stage 3 and 4. It is aimed at students of Drama, Theatre Studies, Performing Arts and English Literature. Chigger Foot Boys is also an ideal text for exploring cross-curricular links, especially History and Citizenship at Key Stages 3 and 4. Chigger Foot Boys is co-production between Strongback Productions, a Black Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME) company developing and creating new work for diverse audiences, and Tara Arts, a gorgeous award- winning new theatre dedicated to connecting worlds through multicultural arts. -

The Strangers

Belonging and a sense of place Patricia Cumper I was once told off by my then partner for mocking a couple who had walked past us. They were deep in a lively conversation. After they passed us, I repeated what I had heard them say. I did out loud what I have always done in my head. I repeated what I heard around me. For me it was not what was said, or even the accent in which it was said, it was the intangibles: the rhythm within the words, the rise and fall of the voices, the force or softness of the delivery that had caught my attention. When I came to live in the UK a quarter century ago, I was ignorant of the stereotypes, assumptions, and snobberies that underpin social interactions in the UK. There was as much music for me in a Scouse as in a Hampstead voice. Their turns of phrase were equally fascinating. The streets of London, bubbling with conversations in languages and accents from all over the country, all over the world, was a rich and varied learning ground. A bus ride, listening to the chatter of half a dozen schoolchildren, broadened my vocabulary. It was almost overwhelming. How do I write characters from this world so that they ring true? I had spent years in Jamaica writing and producing nearly a thousand episodes of radio soaps. The studio conditions were basic but the technical operators and the actors I worked with were brilliant. I learnt when to get in and out of scenes, how to differentiate characters through accent, rhythm, age, even intent. -

WRAP THESIS Johnson2 2001.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/3070 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. David Johnson Total Number of Pages = 420 The History, Theatrical Performance Work and Achievements of Talawa Theatre Company 1986-2001 Volume II of 11 By David Vivian Johnson A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in British and Comparative Cultural Studies University of Warwick, Centre for British and Comparative Cultural Studies May 2001 Table of Contents VOLUME 11 5. Chapter Five American Plays 193-268 ................................................ 6. Chapter Six English Plays 269-337 ................................................... 7. ChapterSeven Conclusion 338-350 ..................................................... Appendix I David Johnsontalks to Yvonne Brewster LouiseBennett 351-367 about ......................................... Appendix 11 List Talawa.Productions 368-375 of ................................... Bibliography 376-420 .......................................................................... AmericanPlays Johnson 193 CHAPTER FIVE AMERICAN PLAYS This chapteraims to demonstratesome of what TalawaTheatre -

WRAP THESIS Johnson1 2001.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/3070 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. David Johnson Total Number of Pages = 420 The History, Theatrical Performance Work and Achievements of Talawa Theatre Company 1986-2001 Volume I of 11 By David Vivian Johnson A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in British and Comparative Cultural Studies University of Warwick, Centre for British and Comparative Cultural Studies May 2001 Table of Contents VOLUMEI 1. Chapter One Introduction 1-24 ..................................................... 2. Chapter Two Theatrical Roots 25-59 ................................................ 3. ChapterThree History Talawa, 60-93 of ............................................. 4. ChapterFour CaribbeanPlays 94-192 ............................................... VOLUME 11 5. ChapterFive AmericanPlaYs 193-268 ................................................ 6. ChapterSix English Plays 269-337 ................................................... 7. ChapterSeven Conclusion 338-350 ..................................................... Appendix I David Johnsontalks to.Yv6nne Brewster Louise -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Current feminist theatre scholarship tends to use the term ‘heteronormative’. The predominant use of the term ‘heterosexist’ in this study draws directly from black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde’s notion of ‘Heterosexism [as] the belief in the inherent superiority of one pattern of loving and thereby its right to dominance’ (Lorde, 1984, p. 45). 2. See Diana Fuss, Essentially Speaking: Feminism, Nature and Difference (London: Routledge, 1989) for summaries and discussions of the essen- tialism/constructionism debates. 3. See, for example, Elaine Aston, An Introduction to Feminism and Theatre (London: Routledge, 1995); Elaine Aston, Feminist Views on the English Stage: Women Playwrights, 1990–2000 (Cambridge: CUP, 2003); Mary F. Brewer, Race, Sex and Gender in Contemporary Women’s Theatre: The Construction of ‘Woman’ (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 1999); Lizbeth Goodman, Contemporary Feminist Theatres: To Each Her Own (London: Routledge, 1993); and Gabriele Griffin Contemporary Black and Asian Women Playwrights in Britain (Cambridge: CUP, 2003). 4. See, for example, Susan Croft, ‘Black Women Playwrights in Britain’ in Trevor R. Griffiths and Margaret Llewellyn Jones, eds, British and Irish Women Dram- atists Since 1968 (Buckingham: OUP, 1993); Mary Karen Dahl, ‘Postcolonial British Theatre: Black Voices at the Center’ in J. Ellen Gainor, ed., Imperi- alism and Theatre: Essays on World Theatre, Drama and Performance (London: Routledge, 1995); Sandra Freeman, Putting Your Daughters on the Stage: Lesbian Theatre from -

An Open Letter to Theatre and Performance Makers

An open letter to theatre and performance makers This is a letter to self-employed theatre makers in the UK. This includes • actors • writers • directors • choreographers • stage managers • designers • set builders who are freelance or self- employed. This letter is from theatre and performance companies and venues. We want to say that we miss you. We miss making performance together. We know we won’t be able to do this again for some time. We know that you might be feeling worried about the future. Things feel very uncertain for theatre at the moment. Many self- employed people are worried about their jobs. We want to support you. We want to help to improve the situation. We are exploring new ways of working with self-employed people during lockdown. We are using this time to plan for future projects with self-employed people. We are asking the government to keep the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme going until theatres can re-open safely. We are asking the government to make sure self-employed people aren’t stopped from getting help if they need it. The Self-Employment Income Support Scheme is a way the government is giving financial help to self-employed people who are missing out on work because of lockdown We want to help to make a national task force of self- employed theatre makers. This will be a group of self- employed people who: • make sure self-employed people’s voices are heard in conversations about the future • make sure organisations are talking to self-employed people about what their needs are Every organisation on this letter will support a self-employed person to join the task force. -

The Strangers

Why do I write? Patricia Cumper Although I wrote my first play at 23, my writing life began years earlier. I always got good marks at school. I was clever and I came from a clever family, said my teachers. The truth was a little more complex. I have always read copiously: from the Bobbsey Twins and Nancy Drew stories of my childhood to holiday reading by Agatha Christie, Georgette Heyer and Ellis Peters. I read Jamaican writers like Erna Brodber, Jean D’Costa, Olive Senior and Lorna Goodison; I learnt something of the Jewish experience from Anne Frank and Leon Uris; about the wider Caribbean from Andrew Salkey, Kamau Brathwaite and Derek Walcott; the lives of Black Americans through the words of Alice Walker, Toni Cade Bambara and Toni Morrison. Indeed, when I eventually came to university in England, I wanted to be sure that I was not at a disadvantage so I set myself the task of reading the classics. I got as far as all of Shakespeare’s plays and most of his son- nets, the Brontë sisters’ books, and D. H. Lawrence’s short stories Love Among the Haystacks but sadly stalled a hundred or so pages into Crime and Punishment. I also grew up in a household where debate was the most popular occupation. Not arguing. I only ever heard my parents argue once in my whole childhood and it shook me to the core, it was that aberrant. We – my brother, sister and I – debated. Over dinner. In the back of the old family Volkswagen. -

Radio 4 Listings for 16 – 22 June 2018 Page 1 of 13 SATURDAY 16 JUNE 2018 the Latest Weather Forecast

Radio 4 Listings for 16 – 22 June 2018 Page 1 of 13 SATURDAY 16 JUNE 2018 The latest weather forecast. Producer: Joe Kent. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b0b5qnnj) The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. SAT 07:00 Today (b0b6bt9r) SAT 12:00 News Summary (b0b5qnp7) Followed by Weather. News and current affairs. Including Yesterday in Parliament, The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Sports Desk, Weather and Thought for the Day. SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b0b5xh1p) SAT 12:04 Money Box (b0b6btzq) The Wind in My Hair, My Stealthy Freedom SAT 09:00 Saturday Live (b0b5qnp3) Legal action planned over training costs Masih finds that she is no longer safe in Tehran working as a Alison Balsom meets Aasmah Mir and Konnie Huq The latest news from the world of personal finance. political journalist. She is forced into exile during the Iranian With Aasmah Mir and guest presenter Konnie Huq are elections of 2009 but finds a way to protest against the Islamic trumpeter Alison Balsom OBE, cycling blogger Jools Walker, Republic with her online movement. self taught Fungi expert Geoff Dann and Joanne Barton who SAT 12:30 Dead Ringers (b0b5xh2x) went from teenage alcoholism to becoming a doctor in A&E. Series 18, Episode 2 Masih Alinejad is a journalist and activist from a small village Recorded at Venue Cymru as part of the Craft of Comedy in Iran. In 2014 she sparked a social media movement when she Alison Balsom is having a break from travelling the world Festival in Llandudno. -

Programmer for the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival and Is Currently Artistic Director of the Red Room Theatre and Film Company

exploring the canon What makes a play a classic? Wednesday 9 February 2011 exploring 11am – 5.30pm the canon is a day of performance readings looking beyond the usual suspects to widen the repertoire of British Theatre The Artistic Directors from The London Hub of Sustained Theatre want to look beyond the plays that are generally regarded as classics to champion plays that they think should be accorded canonical status . Theatre directors; Mukul Ahmed, Katharine Armitage, Renu Arora, Topher Campbell, Tunde Euba, Simeilia Hodge-Dallaway, Trilby James, and Josephine Melville have worked closely with Artistic Directors from Arcola Theatre, ATC, Collective Artistes, Kali Theatre Company, Talawa Theatre Company, Tamasha, Tara and The Red Room to direct a series of extracts from diverse plays that are often neglected for revival in the national theatre landscape. The plays: Moon on a Rainbow Shawl by Errol John, directed by Simeilia Hodge-Dallaway Borderline by Hanif Kureishi, directed by Mukul Ahmed Death and the King’s Horseman by Wole Soyinka, directed by Tunde Euba The House of Bilquis Bibi by Sudha Bhuchar, directed by Renu Arora To Rahtid by Sol B. River, directed by Topher Campbell Calcutta Kosher by Shelley Silas, directed by Trilby James Alterations by Michael Abbensetts, directed by Josephine Melville Wedding Band: A Love/Hate Story in Black and White by Alice Childress, directed by Katharine Armitage exploring Wednesday 9 February 2011 the canon ATC presents: Moon on a Rainbow Shawl by Errol John Directed by: Simeilia Hodge-Dallaway Artistic Director: Ramin Gray Synopsis Holder, Dystin Johnson, James Earls Jones Ramin Gray and Cicely Tyson who have all starred in Errol John's Moon on a Rainbow Shawl is After directing, pervious productions.