The European Journal of Life Writing Kenneth Womack, Maximum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1969 in Review (Con't from Page 3) Disney and Buena Vista Recordings Leaves CBS and Sandy Roberton Chap- Left the Rolling Stones Group

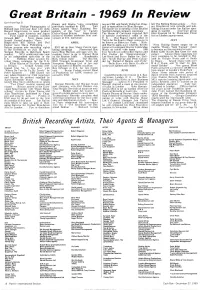

Great Britain -1969 In Review (Con't From Page 3) Disney and Buena Vista recordings leaves CBS and Sandy Roberton Chap- left The Rolling Stones group ... War- majors . Philips Phonographic of previously handled by EMI . Tom pell to open office for Blue Horizon .. ner Bros -Seven Arts records and pub- Holland sign five-year deal with indie Jones named "Show Business Per- The battle for ownership of the Beatles lishing division under Ian Ralfini oper- Record Supervision to issue product sonality of the Year" by Variety Northern Songs company continues .. ating in London . American group in Europe, Latin America and Japan Club of Great Britain ... Sonet Gram- The House of Commons rejected Bill Ohio Express hit by Musicians Union First ripple of economy rumbles mofon of Sweden celebrate first anni- to operate commercial radio in the ban re London appearances. through BBC . Terry Oates joins versary of U.K. operation. U. K. Hal Shaper opens office in Screen Gems -Columbia Music Tokyo for his Sparta Music company to JULY Songwriters Bill Martin and Phil APRIL be known as Sideways Music.. Rich- Coulter form Mews Publishing . ard Harris signs pact whereby Screen First Rolling Stones single for 14 Delyse acquire sole recording rights EMI set up their Music Centre mar- Gems will represent Harris' Limbridge months "Honky Tonk Women" (later to the Investiture on July 1st keting campaign . Fleetwood Mac Music on world wide basis . 1968 to become an international smash) .. Morgan Records to distribute Spark leave Blue Horizon and sign with Im- Ivor Novello awards to Bill Martin and Robin Gibb leaves Bee Gees for solo product MCA celebrated one year mediate (later to go to Warner Bros Phil Coulter for "Congratulations"; career .. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

Observations & Questions Contexts & Consequences Meet the Beatles

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Meet The Beatles Hearts Club Albums recorded 1963-1970 Band An album by the Beatles December 1966 – April 1967 “perhaps the most creative 129 days in the history of rock music” 1964 Observations & questions Producer George Martin • Song analysis models “The 5th Beatle” • Is this album a unified work of art similar to a symphony, suite or song cycle in classical music? – The invention of the “concept album” – McCartney “. like writing your novel” – Lennon disagreed – The first album to print the lyrics on the sleeve contexts & consequences ‘The Frame’ • Pop music gets its own Art Tradition • Opening (title) song (SPLHCB) • Queen – “We don’t compose songs, we compose albums” • Alter ego/distancing (dissimulation) tactic • Punk reacts against this (Metallica struggles on) • Polystylistic now, polystylistic then, but in the • The Recording is the Work future? – Before, recordings were supplements to the ‘real thing,’ live performance • 12 + 5 bar phrase lengths – gives it a chopped – Now, the live concert is the supplement to the up feel? recording – Financially, this may be reverting back, but the recording still seems to be the site of music With a Little Help . Getting Better • A “character song” (as in an opera or musical) • Optimism with one or two negative, even • Musical traits? (Simplicity of harmony seems shocking, twists in the lyrics to set up the next song) • “the album’s first track with no harmonic • Drug reference? Surrealistic verse? innovations” – Walter Everett • Rating on your personal normalcy/weirdness – (but I think that guitar spiking away on a note that chart? may or may not fit into the chords is really cool) • Falsetto “foolish rules” • Appeal to fantasies/Beatlemania? With a Little Help . -

The Beatles in Context Edited by Kenneth Womack Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-41911-6 — The Beatles in Context Edited by Kenneth Womack Frontmatter More Information THE BEATLES IN CONTEXT Since their first performances in 1960, the Beatles’ cultural influence grew in unparalleled ways. From Liverpool to Beatlemania, and from Dance Halls to Abbey Road Studios and the digital age, the band’s impact exploded during their heyday, and has endured in the decades following their disbandment. Beatles’ fashion and celebrity culture, politics, psychedelia and the Summer of Love, all highlight different aspects of the band’s complex relationship with the world around them. With a wide range of short, snapshot chapters, The Beatles in Context brings together key themes in which to better explore the Beatles’ lives and work and understand their cultural legacy, focusing on the people and places central to the Beatles’ careers, the visual media that contributed to their enduring success, and the culture and politics of their time. kenneth womack is Dean of the Wayne D. McMurray School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Monmouth University, where he also serves as Professor of English. He is the author or editor of numerous books, including Long and Winding Roads (2007), Cambridge Companion to the Beatles (2009), and The Beatles Encyclopedia (2014). More recently, he is the author of a two-volume biography of Beatles producer George Martin, including Maximum Volume: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin (The Early Years, 1926–1966) and Sound Pictures: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin (The Later Years, 1966–2016). © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-41911-6 — The Beatles in Context Edited by Kenneth Womack Frontmatter More Information composers in context Understanding and appreciation of musical works is greatly enhanced by knowledge of the context within which their composers lived and worked. -

Common Course Outline the Community College of Baltimore

Common Course Outline MUSC 128 The Beatles in the Rock Generation 3 Semester Hours The Community College of Baltimore County Description The Beatles in the Rock Generation Examines the development of the musical and lyrical artistry of the Beatles presented within the framework of aesthetic and social movement, 1957 to 1970. Corequisites: ENGL 051 or ESOL 051 or LVE 1 or LVE 2 or LVE 3 and RDNG 052 or LVR 2. Overall Course Objectives Upon successful completion of this course, the student will be able to: 1. Understand and articulate how and why the Beatles became the most influential pop group of the 1960’s and beyond. 2. Identify the principal musical and social influences on the Beatles. 3. Evaluate the growth and change of the Beatles' body of work as their career progressed. 4. Identify the influence the Beatles had on the music that succeeded them. 5. Evaluate the Beatles’ contribution to the cultural and social climate of the 1960's. 6. Trace the development of popular music in the 20th century. 7. Identify the stylistic and formal aspects of popular music. 8. Articulate the importance of music in human experience. 9. Utilize analytical and critical listening and thinking skills in evaluating music. Major Topics 1. A brief history of popular music; the Beatles early career, 1957-1963 a. Influences: Post-World War II popular music, Anglo-Irish folk music, English Music Hall/European Cabaret, American Rock and Roll: Elvis, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Buddy Holly, Everly Bros., etc. b. Performances: Hamburg, Cavern Club c. Recordings: The Beatles Live at the BBC, Live at the Star Club, The Early Beatles, Please Please Me, With the Beatles, Past Masters Vol. -

BEATLES Blossom Music Center 1145 West Steels Corners Road Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio 44223 Sunday, August 8, 2021, at 7 P.M

Blossom Festival Week Six The Cleveland Orchestra CLASSICAL MYSTERY TOUR: CONCERT PRESENTATION A TRIBUTE TO THE BEATLES Blossom Music Center 1145 West Steels Corners Road Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio 44223 Sunday, August 8, 2021, at 7 p.m. THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA with Classical Mystery Tour Jim Owen, rhythm guitar, piano, vocals Tony Kishman, bass guitar, piano, vocals Tom Teeley, lead guitar, vocals Chris Camilleri, drums, vocals conducted by Martin Herman PART ONE Let It Be (instrumental opening) Songs including “Eleanor Rigby,” “Yesterday,” “Penny Lane,” and “With a Little Help from My Friends” There will be one 20-minute intermission. PART TWO Songs including “Yellow Submarine,” “Dear Prudence,” “Lady Madonna,” and “The Long and Winding Road” This PDF is a print version of our digital online Stageview program book, available at this link: stageview.co/tco ____________________________ 2021 Blossom Music Festival Presenting Sponsor: The J.M. Smucker Company This evening’s concert is sponsored by The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company. Classical Mystery Tour’s appearance with The Cleveland Orchestra is made possible by a gift to the Orchestra’s Guest Artist Fund from The Hershey Foundation. Copyright © The Cleveland Orchestra and Musical Arts Association. All rights reserved. 1 Week Six: 2021 Blosom Music Festival — August 8: Tribute to The Beatles CONCERT OVERVIEW A H A L F C E N T U R Y after they disbanded, it is still diffi cult to fully recognize how much of a force The Beatles were in shaping — and being shaped by — the 1960s and our sense of the modern world. Not just changing music, but in trans- forming the idea and ideals of popular entertainment popular entertainment. -

George Martin Ampmmpmmhi

H- -. l M BÜM H PH M H M mmmmmmmmi r nr nr n» MÜiNMIi MMiMIliPli NnWMpMNMIMilMl George Martin aMpMMpMMHI n the nine years the Beatles were together, their music changed as they did, as the times did, as the world did. But through all the jumps in their sound, there were five common grounds: Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, Starr and the real fifth Beade, George Martin, h © From “ Love Me Do” to “ Let It Be,” it was Martin at the baton, arranging the music, producing the record ings, helping make John and Paul’s musical inventions and dreams come true and, when the four young men began to take the reins in the studio, knowing enough - well, to let them be. hs Perhaps George Martin’s greatest contribution to the Beades story was making it possible to be told at all. hs In the early Sixties in London, every record company, every A & R man, every producer, it seems, turned down the Beades - until they got to f i r hero. And even Martin wasn’t sure aged them to “think symphonically.” The Beades, what he had on his hands that day in February he admitted, resisted, but the proof of his impact 1962, when he listened as Brian Epstein played on them is in such landmark recordings as Sgt. their demonstration tape. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Abbejji] Its quality, he recalled, was “ appalling.” The Road; in songs like “Because” (which Lennon band’s repertoire ranged from saccharine standards based on Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” ) and like “ Over the Rainbow” to a Fats Waller classic, “%sterdayf5)' “ Your Feet’s Too Big.” Not exactly rock & rolL Having enjoyed a career of working with the best Within a year, the Beatles had conquered and the brightest - he has also produced recordings England. -

Abbey Road Institute PR FINAL for Website

Abbey Road Studios Announce New Educational Institute The world famous Abbey Road Studios have announced their first foray into education with the launch of Abbey Road Institute. This international initiative will offer a 12 month Advanced Diploma in Music Production and Sound Engineering aimed at students aged 18 and over in locations around the world including the UK, Germany and Australia. The curriculum, developed by audio educational specialists in conjunction with Abbey Road Studios engineers, offers a unique mix of theoretical and practical modules designed to equip students for their first step toward a professional audio engineering and production career. The course also covers other areas of the music industry, including studio management and music business administration. The course will be taught by qualified lecturers and recognised music industry experts including producers and label execs alongside guest lectures from Abbey Road Studios engineers. Peter Cobbin, Senior Director of Engineering at Abbey Road Studios said of the initiative, “Abbey Road Institute benefits from the studios’ 80 years of audio expertise, distilling some of our knowledge into a curriculum of classroom learning and practical studio experience. I’m delighted that the Institute will nurture and inspire a new generation of audio professionals.” The London Institute will be housed in the legendary north London studio complex and will provide students with access to brand new, purpose-built classroom and studio facilities. Students will also have the opportunity to use Abbey Road’s hallowed recording spaces, control rooms and equipment. Luca Barassi, a qualified audio engineer with 12 years experience in audio education will head up Abbey Road Institute, London. -

Bachelorarbeit Im Studiengang Audiovisuelle Medien

Bachelorarbeit im Studiengang Audiovisuelle Medien Der Einfluss der Beatles auf die Musikproduktion *VORGELEGT VON DOMINIK STUHLER 1 INCH X 1800 FEET *AM 6. JULI 2016 zur Erlangung des Grades BACHELOR of Engineering *ERSTPRÜFER: PROF. OLIVER CURDT *ZWEITPRÜFER: PROF. JENS-HELGE HERGESELL Bachelorarbeit im Studiengang Audiovisuelle Medien Der Einfluss der Beatles auf die Musikproduktion vorgelegt von Dominik Stuhler an der Hochschule der Medien Stuttgart am 6. Juli 2016 zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Bachelor of Engineering. Erstprüfer: Prof. Oliver Curdt Zweitprüfer: Prof. Jens-Helge Hergesell Erklärung Hiermit versichere ich, Dominik Stuhler, ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Bachelorarbeit mit dem Titel: „Der Einfluss der Beatles auf die Musikproduktion“ selbstständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel benutzt habe. Die Stellen der Arbeit, die dem Wortlaut oder dem Sinn nach anderen Werken entnommen wurden, sind in jedem Fall unter Angabe der Quelle kenntlich gemacht. Die Arbeit ist noch nicht veröffentlicht oder in anderer Form als Prüfungsleistung vorgelegt worden. Ich habe die Bedeutung der ehrenwörtlichen Versicherung und die prüfungsrechtlichen Folgen (§26 Abs. 2 Bachelor-SPO (6 Semester), § 24 Abs. 2 Bachelor-SPO (7 Semester), § 23 Abs. 2 Master-SPO (3 Semester) bzw. § 19 Abs. 2 Master-SPO (4 Semester und berufsbegleitend) der HdM) einer unrichtigen oder unvollständigen ehrenwörtlichen Versicherung zur Kenntnis genommen. Stuttgart, 4. Juli 2016 Dominik Stuhler Kurzfassung Die Beatles gehören zu den einflussreichsten Bands des 20. Jahrhunderts. Von einer Beat-Band unter vielen wandelten sie sich zu Künstlern, die die Pop- und Rockmusik revolutionierten. Ihr enormer Erfolg ermöglichte ihnen Arbeitsbedingungen im Tonstudio, die so anderen Musikern nicht möglich gewesen wären. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

Preowned 1970S Sheet Music

Preowned 1970s Sheet Music. PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE Offers Not priced – Offers please. ex No marks or deteriation Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside. Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered.. Year Year of print. Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover STAMP OUT FORGERIES. Warning: It has come to our attention that there are sheet music forgeries in circulation. In particular, items showing Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard, The Beatles and Gene Vincent have recently been discovered to be bootleg reprints. Although we take every reasonable precaution to ensure that the items we have for sale are genuine and from the period described, we urge buyers to verify purchases from us and bring to our attention any item discovered to be fake or falsely described. The public can thus be warned and the buyer recompensed. Your cooperation is appreciated. 1970s Title Writer and composer condition Photo year Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a © 1970 All around my hat Hart/Prior/Knight/Johnson/Kemp ex Steeleye Span 1975 All creatures great and small Johnny Pearson good sheep grazing 1977 All I ever need is you J.Holiday/E.Reeves ex Sonny & Cher 1972 All I think about is you Harry Nilsson ex Harry Nilsson 1977 Amanda Brian Hall ex Stuart Gillies 1973 Amarillo (is this the way to) N.Sedaka/H.Greenfield ex Tony Christie 1971 Amazing grace Trad.