Festschrift for Henryhoenigswald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies on Language Change. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 34

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 286 382 FL 016 932 AUTHOR Joseph, Brian D., Ed. TITLE Studies on Language Change. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 34. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Dept. of Linguistics. PUB DATE Dec 86 NOTE 171p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) -- Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Arabic; Diachronic Linguistics; Dialects; *Diglossia; English; Estonian; *Etymology; Finnish; Foreign Countries; Language Variation; Linguistic Borrowing; *Linguistic Theory; *Morphemes; *Morphology (Languages); Old English; Sanskrit; Sociolinguistics; Syntax; *Uncommonly Taught Languages; Word Frequency IDENTIFIERS Saame ABSTRACT A collection of papers relevant to historical linguistics and description and explanation of language change includes: "Decliticization and Deaffixation in Saame: Abessive 'taga'" (Joel A. Nevis); "Decliticization in Old Estonian" (Joel A. Nevis); "On Automatic and Simultaneous Syntactic Changes" (Brian D. Joseph); "Loss of Nominal Case Endings in the Modern Arabic Sedentary Dialects" (Ann M. Miller); "One Rule or Many? Sanskrit Reduplication as Fragmented Affixation" (Richard D. Janda, Brian D. Joseph); "Fragmentation of Strong Verb Ablaut in Old English" (Keith Johnson); "The Etymology of 'bum': Mere Child's Play" (Mary E. Clark, Brian D. Joseph); "Small Group Lexical Innovation: Some Examples" (Christopher Kupec); "Word Frequency and Dialect Borrowing" (Debra A. Stollenwerk); "Introspection into a Stable Case of Variation in Finnish" (Riitta Valimaa-Blum); -

Paninian Studies

The University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies MICHIGAN PAPERS ON SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA Ann Arbor, Michigan STUDIES Professor S. D. Joshi Felicitation Volume edited by Madhav M. Deshpande Saroja Bhate CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Number 37 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress catalog card number: 90-86276 ISBN: 0-89148-064-1 (cloth) ISBN: 0-89148-065-X (paper) Copyright © 1991 Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-064-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-89148-065-5 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12773-3 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90169-2 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ CONTENTS Preface vii Madhav M. Deshpande Interpreting Vakyapadiya 2.486 Historically (Part 3) 1 Ashok Aklujkar Vimsati Padani . Trimsat . Catvarimsat 49 Pandit V. B. Bhagwat Vyanjana as Reflected in the Formal Structure 55 of Language Saroja Bhate On Pasya Mrgo Dhavati 65 Gopikamohan Bhattacharya Panini and the Veda Reconsidered 75 Johannes Bronkhorst On Panini, Sakalya, Vedic Dialects and Vedic 123 Exegetical Traditions George Cardona The Syntactic Role of Adhi- in the Paninian 135 Karaka-System Achyutananda Dash Panini 7.2.15 (Yasya Vibhasa): A Reconsideration 161 Madhav M. Deshpande On Identifying the Conceptual Restructuring of 177 Passive as Ergative in Indo-Aryan Peter Edwin Hook A Note on Panini 3.1.26, Varttika 8 201 Daniel H. -

Rep.Ort Resumes

REP.ORT RESUMES ED 010 471 48 LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDY PROGRAMSIN AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES. BY MOSES, LARRY OUR. OF INTELLIGENCE AND RESEARCH, WASHINGTON, 0.Ce REPORT NUMBER NDEA VI -34 PUB DATE 64 EDRS PRICEMF40.27HC $7.08 177P. DESCRIPTORS *LANGUAGE PROGRAMS, *AREA STUDIES, *HIGHER EDUCATION, GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS, COURSES, *NATIONAL SURVEYS, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, AFRICA, ASIA, LATIN AMERICA, NEAR EAST, WESTERN EUROPE, SOVIET UNION, EASTERN EUROPE . LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDY PROGRAMS OFFERED IN 1964 BY UNITED STATES INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION ARE LISTEDFOR THE AREAS OF (1) AFRICA, (2) ASIA,(3) LATIN AMERICA, (4) NEAR EAST,(5) SOVIET UNION AND EASTERN EUROPE, AND (6) WESTERN EUROPE. INSTITUTIONS OFFERING BOTH GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMS IN LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDIESARE ALPHABETIZED BY AREA CATEGORY, AND PROGRAM INFORMATIONON EACH INSTITUTION IS PRESENTED, INCLUDINGFACULTY, DEGREES OFFERED, REGIONAL FOCUS, LANGUAGE COURSES,AREA COURSES, LIBRARY FACILITIES, AND.UNIQUE PROGRAMFEATURES. (LP) -,...- r-4 U.,$. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION AND WELFARE I.: 3 4/ N- , . Office of Education Th,0 document has been. reproducedexactly as received from the petson or organization originating it. Pointsof View or opinions CD st4ted do not necessarily representofficial Office of EdUcirtion?' ri pdpition or policy. CD c.3 LANGUAGEAND AREA "Ai STUDYPROGRAMS IN AMERICAN VERSITIES EXTERNAL RESEARCHSTAFF DEPARTMENT OF STATE 1964 ti This directory was supported in part by contract withtheU.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. -

REVIEWS/COMPTES RENDUS George Cardona. Recent Research

Book review: G.Cardona.Recent research in Paninian studies.Delhi,1999 Kulikov, L.I. Citation Kulikov, L. I. (2004). Book review: G.Cardona.Recent research in Paninian studies.Delhi,1999. Canadian Journal Of Linguistics, 49. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15681 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15681 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). REVIEWS/COMPTES RENDUS 121 George Cardona. Recent Research in P¯an. inian Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. 1999. Pp. xi + 371. Rs. 395 [approx. $9.00] (hardcover). Reviewed by Leonid Kulikov, University of Nijmegen The book under review surveys the studies on P¯an.ini, a great Old Indian grammarian (around 600–500 B.C.), one of the most outstanding linguists who ever lived, whose contri- bution to language science cannot be overestimated. His grammatical treatise As.t.¯adhy¯ay¯ı (lit. `consisting of eight chapters/books'), representing in a very condensed form the rules of the Sanskrit grammar, is an impressive specimen of the use of several sophisticated de- scriptive techniques, anticipating a number of theoretical notions (such as zero morpheme, semantic roles, etc.), which modern linguistics has only developed in the last century. No wonder P¯an.ini's work constantly draws the attention of scholars both in and outside India, and not only that of Sanskritists, so that P¯an.inian studies can be said to represent a solid separate branch of research on the history and theory of linguistics. The author of this survey, the American linguist George Cardona (GC), is one of the most authoritative modern P¯an.inian scholars, who happily combines the achievements of 122 CJL/RCL 49(1), 2004 modern Western linguistics with the indigenous tradition of the study of Pan¯ .ini's grammar, preserved in India for two and a half thousand years, as attested in detailed commentaries and sub-commentaries on As.t.adhy¯ ay¯ ¯ı. -

UCLA LAW MAGAZINE PRESORTED UCLA School of Law, Office of the Dean FIRST CLASS MAIL Box 951476, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1476 U.S

Final Cover 3/26/01 10:13 AM Page 1 UCLA LAW MAGAZINE PRESORTED UCLA School of Law, Office of the Dean FIRST CLASS MAIL Box 951476, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1476 U.S. POSTAGE PAID www.law.ucla.edu UCLA [email protected] APRIL 2001 Return Service Requested Friday, April 20, 1 P.M. “The Changing Face of Practice: Perspectives from the Profession and the Law School” A Symposium to mark the 30th Anniversary of the UCLA School of Law Clinical Program with a dinner and tribute to Professor David Binder UCLA LAW MAGAZINE UC L A featuring Shirley M. Hufstedler LAW MAGAZINE The Magazine of the UCLA School of Law MCLE credit approved for 2.5 hours general credit and 1.75 ethics credit Vol. 24 L No. 1 L Fall.Winter.2000.2001 Please call (310) 825-7376 or e-mail [email protected] • Saturday, April 21, 9 A.M.- 6 P.M. AALS Colloquium: Equal Access to Justice Please call (310) 206-9155 or e-mail [email protected] 3030 YearsYears ofof Clinical Clinical LegalLegal EducationEducation • Tuesday, April 24, NOON UCLA Law Alumni of the Year Awards A Salute to The Honorable Elwood Lui [Ret.] ’69 Public/Community Service and N Skip Brittenham ’70 FALL.WINTER.2000–2001 Professional Achievement Century Plaza Hotel Please call (310) 206-1121 or e-mail [email protected] • Tuesday, April 24, 4:30 P.M. The Twelfth Annual Public Interest Awards UCLA School of Law, Room 1430 Please call (310) 206-9155 or e-mail [email protected] MAY 2001 Sunday, May 20, 2 P.M. -

Modeling the Pāṇinian System of Sanskrit Grammar

i i i “more-formulas” — 2019/4/12 — 15:15 — page 1 — #1 i i i i i “more-formulas” — 2019/4/12 — 15:15 — page 1 — #1 i i “more-formulas”i — 2019/4/12 — 15:15 — page 1 — #1 i i i 1 i “rule111” — 2019/4/10 — 15:48 — page 1 — #1 i i +a:— i i i X+a X[ ] ∥ — i i “rule1410” —1 2019/4/10“structure01” — 16:02 — 2019/4/10 — page 1 — — 15:54 #1 — page 1 — #1 i i 1 i i 2 +a: vṛddhi +a:— Xm+ai Xm X+a X[“more-formulas”—] — 2019/4/12 — 15:15 — page 1 — #1 i +a:+a: guṇa1. ∥ [āt, aic] ∥ — i i X+a व1.X[�����ृ Xm+a—चै ]॥१.१.१॥् Xm[at,eṅ] ∥i +a:∥ +a: i +a: vṛddhiguru — अद�े णःु i ॥१.१.२॥ i Xm+a2 Xm[ ] “structure03” — 2019/4/10 — 16:12 — page 1 — #1 i i Xm+a Xm ∥ Xn — 1. Xm+a1. Xm[ā∥t, aic[hrasva]] ∧ [saṃyoga] i ∥ “more-formulas”+a: — 2019/4/12 — 15:15 — page 1 — #1 i Xm+a Xm —+a: guṇa 2 ् 2. ∥ [dīrgha]Xm+a Xm[ ] व�����ृ चै ॥१.१.१॥ 1∥ — i3 1. Xm+a“rule111”Xm[at,eṅ] — 2019/2/8 — 14:44 — page 1 — #1 i +a: vṛddhi��ं लघु ॥१.४.१०॥ सयोगं+a:े ग—�ु ॥१.४.११॥ ��घ∥ � च ॥१.४.१२॥ Xm+a+a:Xm[— ] +a:+a:guṇa+a:Xm+aguruXm अद�े णःु — ॥१.१.२॥ ghai1. -

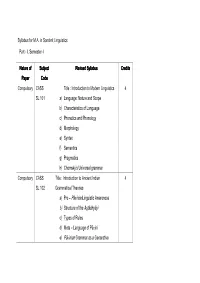

M.A. Part -I, in Sanskrit Linguistics

Syllabus for M.A. in Sanskrit Linguistics Part - I, Semester -I Nature of Subject Revised Syllabus Credits Paper Code Compulsory CASS Title : Introduction to Modern Linguistics 4 SL 101 a) Language: Nature and Scope b) Characteristics of Language c) Phonetics and Phonology d) Morphology e) Syntax f) Semantics g) Pragmatics h) Chomsky’s Universal grammar Compulsory CASS Title : Introduction to Ancient Indian 4 SL 102 Grammatical Theories a) Pre – Pāṇinian Linguistic Awareness b) Structure of the Aṣṭādhyāyi c) Types of Rules d) Meta – Language of Pāṇini e) Pāṇinian Grammar as a Generative Grammar Compulsory CASS Title : Kāraka Theory and Cases 4 SL 103 a) Concepts of Verb and Noun b) Kartā c) Karma d) Kara ṇa e) Sa ṁpradāna f) Apādāna g) Sa ṁbandha h) Adhikara ṇa Optional (1) CASS Title : Post – Pāṇinian Grammatical Traditions 4 SL 104 A) a) Post –Pāṇinian Tradition of the Aṣṭādhyāyi b) Thinkers and their Texts Optional (2) CASS Title : Non – Pāṇinian Grammatical Traditions 4 SL 104 B) a) Non – Pāṇinian Schools of Grammar b) Thinkers and their Texts M.A. in Sanskrit Linguistics Part - I, Semester -II Nature of Subject Revised Syllabus Credits Paper Code Compulsory CASS Title : Phonetics in Ancient India 4 SL 201 a) Study of Linguistic Sounds b) Physiology of Linguistic Sounds c) Organs of Speech d) Articulations of Sounds e) Study of Linguistic Sounds in the Prātiśākhyas f) Study of Linguistic Sounds in the Śikṣas Compulsory CASS Title : Sanskrit Phonology 4 SL202 a) What is Sandhi b) Nature of Sandhi Rules c) Types of Sandhi Compulsory -

Automatic Discovery of Adposition Typology

Automatic Discovery of Adposition Typology Rishiraj Saha Roy Rahul Katare∗ IIT Kharagpur IIT Kharagpur Kharagpur, India – 721302. Kharagpur, India – 721302. [email protected] [email protected] Niloy Ganguly Monojit Choudhury IIT Kharagpur Microsoft Research India Kharagpur, India – 721302. Bangalore, India – 560001. [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Natural languages (NL) can be classified as prepositional or postpositional based on the order of the noun phrase and the adposition. Categorizing a language by its adposition typology helps in addressing several challenges in linguistics and natural language processing (NLP). Understand- ing the adposition typologies for less-studied languages by manual analysis of large text corpora can be quite expensive, yet automatic discovery of the same has received very little attention till date. This research presents a simple unsupervised technique to automatically predict the adpo- sition typology for a language. Most of the function words of a language are adpositions, and we show that function words can be effectively separated from content words by leveraging differ- ences in their distributional properties in a corpus. Using this principle, we show that languages can be classified as prepositional or postpositional based on the rank correlations derived from entropies of word co-occurrence distributions. Our claims are substantiated through experiments on 23 languages from ten diverse families, 19 of which are correctly classified by our technique. 1 Introduction Adpositions form a subcategory of function words that combine with noun phrases to denote their se- mantic or grammatical relationships with verbs, and sometimes other noun phrases. NLs can be neatly divided into a few basic typologies based on the order of the noun phrase and its adposition. -

Robert Philip Goldman Catherine and William L

CURRICULUM VITAE Robert Philip Goldman Catherine and William L. Magistretti Distinguished Professor of Sanskrit Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies University of California, Berkeley 94720–2540 TEL: (510) 642–4089; FAX: (510) 642–2409 EMAIL: rpg@ berkeley.edu Education: Columbia College, Oriental Studies. A.B. 1964. University of Pennsylvania, Oriental Studies. Ph.D. 1971. Employment: The University of Rochester: Assistant Professor of Sanskrit 1970–1971. The University of California at Berkeley: Academic: Assistant Professor of Sanskrit and India Studies, 1971–75. Associate Professor of Sanskrit and India Studies, 1975–79. Professor of Sanskrit and India Studies, 1979–. Sarah Kailath Professor of India Studies, 1996–2000. Professor Above Scale, 2007–. Catherine and William L. Magistretti Distinguished Professor in South and Southeast Asian Studies, 2012— Visiting Professorships Guest Lecturer, Centre for Historical Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University, January–May 2010. Visiting Professor, Department of Philosophy, Jadavpur University, December 2016. Visiting Professor, Department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, December 2017. Administrative Appointments: Chair, Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies, 1981–86, 1993– 98. Associate Chair for South Asia: Center for South and Southeast Asia CV: Robert P. Goldman 2 Studies, 1988–89. Acting Chair, Center for South Asia Studies, 1989. Chair, Center for South Asia Studies, 1990–2000. Co-Visiting Director UCOEAP India Program, 1992. Director, South Asia National Resource Center, 1988–2000 Principal Investigator and Project Director: Berkeley Professional Schools Program in India, 1993–1995. Principal Investigator, Berkeley Urdu Language Program in Pakistan, 1993–2000. Chair, UCOEAP India Formal Review Committee, 2001–2002. Director, UCOEAP Study Center in India, 2004–2007. -

1 CONTENTS Bibliography. Preface. Section I. Chronology And

CONTENTS Bibliography. Preface. Section I. Chronology and Geography of the Rigveda. Ch.1. The Relative Chronology of the Rigveda — I Personal Names in the Avesta. 1A. The Early Rigveda ― Rigvedic Names. 1A-1. The Early Books. 1A-2. The Avesta. 1A-3. The Middle and Late Books. 1A-4. Certain Basic Words. 1B. The Early Rigveda ― Iranian Names. 1C. The Middle Rigveda. 1D. The Late Rigveda. 1D-1. Composer Names. 1D-2. Names in the Text. 1D-3. Other Words in the Text. 1E. Three ―BMAC‖ words in Rigvedic Names. 1F. What the Evidence Shows. 1G. Footnote: An ―Iranian‖ Vasiṣṭha? Ch.2. The Relative Chronology of the Rigveda — I (contd). The Evidence of the Meters. 2A. The Rigvedic Meters. 2B. The Chronology of the Dimeters. 2C. The Chronology of the Other Meters. 2D. The Avestan Meters. Ch.3. The Geography of the RV. 3A. The Eastern Region: the Sarasvatī River and East. 3B. The Western Region: the Indus River and West. 3C. The Central Region: Between the Sarasvatī and the Indus. 3D. Summary of the Data. 3E. Appendix 1: Other Geographical Evidence. 3E-1. Climate and Topography. 3E-2. Trees and Wood. 3E-3. Rice and Wheat. 3E-4. The Traditional Vedic Attitude towards the Northwest. 1 3F. Appendix 2. The Topsy-turvy Logic of AIT Geography. 3F-1. The Sarasvatī. 3F-2. The Gangā. Ch.4. The Internal Chronology of the Rigveda. 4A. The Late Books as per the Western Scholars Themselves. 4B. Can This Evidence be Refuted? 4C. Appendix I: The Internal Order of the Early and Middle Books. -

The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 192 September, 2009 In and Outside the Square: The Sky and the Power of Belief in Ancient China and the World, c. 4500 BC – AD 200 Volume I: The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot by John C. Didier Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series edited by Victor H. Mair. The purpose of the series is to make available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including Romanized Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. The only style-sheet we honor is that of consistency. Where possible, we prefer the usages of the Journal of Asian Studies. -

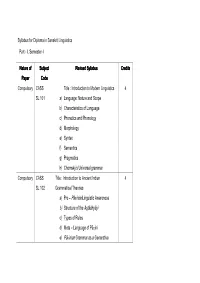

Diploma in Sanskrit Linguistics Part - I, Semester -I

Syllabus for Diploma in Sanskrit Linguistics Part - I, Semester -I Nature of Subject Revised Syllabus Credits Paper Code Compulsory CASS Title : Introduction to Modern Linguistics 4 SL 101 a) Language: Nature and Scope b) Characteristics of Language c) Phonetics and Phonology d) Morphology e) Syntax f) Semantics g) Pragmatics h) Chomsky’s Universal grammar Compulsory CASS Title : Introduction to Ancient Indian 4 SL 102 Grammatical Theories a) Pre – Pāṇinian Linguistic Awareness b) Structure of the Aṣṭādhyāyi c) Types of Rules d) Meta – Language of Pāṇini e) Pāṇinian Grammar as a Generative Grammar Compulsory CASS Title : Kāraka Theory and Cases 4 SL 103 a) Concepts of Verb and Noun b) Kartā c) Karma d) Kara ṇa e) Sa ṁpradāna f) Apādāna g) Sa ṁbandha h) Adhikara ṇa Optional (1) CASS Title : Post – Pāṇinian Grammatical Traditions 4 SL 104 A) a) Post –Pāṇinian Tradition of the Aṣṭādhyāyi b) Thinkers and their Texts Optional (2) CASS Title : Non – Pāṇinian Grammatical Traditions 4 SL 104 B) a) Non – Pāṇinian Schools of Grammar b) Thinkers and their Texts M.A. in Sanskrit Linguistics Part - I, Semester -II Nature of Subject Revised Syllabus Credits Paper Code Compulsory CASS Title : Phonetics in Ancient India 4 SL 201 a) Study of Linguistic Sounds b) Physiology of Linguistic Sounds c) Organs of Speech d) Articulations of Sounds e) Study of Linguistic Sounds in the Prātiśākhyas f) Study of Linguistic Sounds in the Śikṣas Compulsory CASS Title : Sanskrit Phonology 4 SL202 a) What is Sandhi b) Nature of Sandhi Rules c) Types of Sandhi Compulsory