Issues and Options for the Waste Core Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position GL_AVBF05 SP 102 149 UC road (was A40) HAMPNETT West Northleach / Fosse intersection on the verge against wall GL_AVBF08 SP 1457 1409 A40 FARMINGTON New Barn Farm by the road GL_AVBF11 SP 2055 1207 A40 BARRINGTON Barrington turn by the road GL_AVGL01 SP 02971 19802 A436 ANDOVERSFORD E of Andoversford by Whittington turn (assume GL_SWCM07) GL_AVGL02 SP 007 187 A436 DOWDESWELL Kilkenny by the road GL_BAFY07 ST 6731 7100 A4175 OLDLAND West Street, Oldland Common on the verge almost opposite St Annes Drive GL_BAFY07SL ST 6732 7128 A4175 OLDLAND Oldland Common jct High St/West Street on top of wall, left hand side GL_BAFY07SR ST 6733 7127 A4175 OLDLAND Oldland Common jct High St/West Street on top of wall, right hand side GL_BAFY08 ST 6790 7237 A4175 OLDLAND Bath Road, N Common; 50m S Southway Drive on wide verge GL_BAFY09 ST 6815 7384 UC road SISTON Siston Lane, Webbs Heath just South Mangotsfield turn on verge GL_BAFY10 ST 6690 7460 UC road SISTON Carsons Road; 90m N jcn Siston Hill on the verge GL_BAFY11 ST 6643 7593 UC road KINGSWOOD Rodway Hill jct Morley Avenue against wall GL_BAGL15 ST 79334 86674 A46 HAWKESBURY N of A433 jct by the road GL_BAGL18 ST 81277 90989 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON near Leighterton on grass bank above road GL_BAGL18a ST 80406 89691 A46 DIDMARTON Saddlewood Manor turn by the road GL_BAGL19 ST 823 922 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON N of Boxwell turn by the road GL_BAGL20 ST 8285 9371 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON by Lasborough turn on grass verge GL_BAGL23 ST 845 974 A46 HORSLEY Tiltups End by the road GL_BAGL25 ST 8481 9996 A46 NAILSWORTH Whitecroft by former garage (maybe uprooted) GL_BAGL26a SO 848 026 UC road RODBOROUGH Rodborough Manor by the road Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

Meet Marion Bond Artist, Singer, Poet

Ripples SEPT 2019 L&F .qxp_1 LINK – May 07 16/08/2019 12:17 Page 1 September 2019 Ripples SEPT 2019 L&F .qxp_1 LINK – May 07 16/08/2019 12:17 Page 2 MAKING RIPPLES 10 years of making Ripples September It was our late prime minister Harold Wilson who coined the News 4 expression ‘a week is a long time in politics’. As far as I know he was never a publisher but he certainly made a lot of ripples. Believe me, Countryside 12 10 years as Ripples editor is a very long time indeed. Home & Garden 16 Given the short life of most magazines that come and go, especially in this Local History 20 online age, we’re pretty chippa about October being our 100th edition. We hope we’ve served Fairford, Lechlade and surrounding villages well. We Councils 22 still get calls and emails from people wondering ‘where’s my Ripples?’ And Volunteering 24 we enjoy incredible loyalty from our advertisers. So we figure we must be doing something right. Letters 26 What are your thoughts on Ripples? Arts 28 How has it served you since November 2009? Sport 32 What should we improve or change? Business 34 We’d welcome your thoughts by email, letter or give us a call. See contact Wellbeing 38 details below. Profile 40 40th Anniversary – beat that! Pets 42 Our 10 years seems puny when compared with the Fairford Gardeners’ Events 43 Club. See their story ‘Celebrating 40 years of gardening’ on page 18. Are they the ultimate perennials? Contacts 46 How many continuously running clubs are there in Fairford, Lechlade or the villages running for 40 years or more? Veteran gardener Marion Lloyd COVER PICTURE: says: ‘I can think of the WI and perhaps the football and cricket clubs Traction Engines gathered in celebrating more than 40 years. -

13-15 JULY 2018 Is the Airshow’S Very Own Radio Station

16 AIR TATTOO LIVE 87.7FM TIMINGS Friday 13, Saturday 14 & Sunday 15 July On Air 7.00am-9.00pm Run by volunteers, Air Tattoo Live 87.7FM 13-15 JULY 2018 is the airshow’s very own radio station. RIAT 2018 Starting on Friday morning, 13 July, it broadcasts until Sunday evening. This year, TICKETING Air Tattoo Live will feature live commentary of the flying display Friday-Sunday, 10.00am The standard admission ticket price is £55 to 5.30pm. plus admin fee (subject to availability). All accompanied Under-18s* can enter free You can contact Air Tattoo Live 87.7FM for of charge (*2018 only). For details, call dedications, requests or news either by the Ticketline on 0800 107 1940 or visit telephoning 01285 713300 ext 5140 or by www.airtattoo.com. Parking is free for texting to 07797 881188. ticketholders. Please note: tickets must be Courtesy of HSL Mobile www.hslmobile.com purchased in advance as they will not be ANNUAL REVIEW Copies of the RAFCT Annual Review by the RAFCT are available to download at ANIMAL www.rafct.com SAFETY COMMUNITY Please remember the nature of the Air Tattoo means that it is sometimes noisy. HELPLINE Whilst RAFCTE makes every effort to A team of volunteers with excellent airshow minimise any impact caused, it does rely and local knowledge will operate our on residents being prepared, especially Helpline (01285 713000) during the Air those with animals and livestock. If there Tattoo. The team will answer questions and is anyone in the area who has recently endeavour to provide solutions to issues opened new stables or keeps livestock that associated with the airshow. -

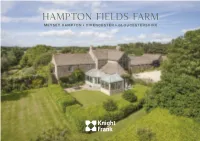

Hampton Fields (Pdf 2017)

Hampton Fields FARM MEYSEY HAMPTON, CIRENCESTER, GLOUCESTERSHIRE Hampton Fields FARM MEYSEY HAMPTON, CIRENCESTER GLOUCESTERSHIRE, GL7 5JL A beautifully Cotswold stone property in an unspoilt private setting Meysey Hampton 1 mile • Cirencester 6 miles • Fairford 2½ miles Swindon (trains to London Paddington 55 mins) 14 miles • M5 (J11A) 15 miles • M4 (J15) 16 miles Cheltenham 20 miles • Oxford 32 miles (Distances and times approximate) Accommodation Reception hall Drawing room Sitting room Dining room Boot room Conservatory Kitchen/breakfast room Utility room WC Master bedroom with en-suite bathroom Four further bedrooms Three further bathrooms Double garage Loft storage Stables Tack room Machinery store Grounds Landscaped gardens and grounds Mature ornamental woodland Paddocks Lot 1 about 8 acres (3.21 hectares) Lot 2 – further pasture and woodland - about 35 acres (14 hectares) Further land available by separate negotiation In all about 43 acres (17 hectares) Cirencester Gloucester House, 60 Dyer Street, Cirencester, Gloucestershire GL7 2PT Tel: +44 1285 659 771 [email protected] These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. Hampton Fields Farm • Hampton Fields Farm occupies a delightfully quiet and secluded setting situated at the end of a long private drive. The house overlooks the beautifully mature gardens and grounds and quintessential Cotswold countryside beyond. The property is not listed and was originally converted in 1990 to provide a particularly light and airy country house. • The reception hall links the open plan kitchen breakfast room, sitting room and conservatory which form the core of the house. -

Applications and Decisions for the West of England 5675

Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Applications and Decisions Publication Number: 5675 Publication Date: 03/12/2020 Objection Deadline Date: 24/12/2020 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 03/12/2020 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. If you wish to make an objection to an application it is recommended you send the details to [email protected]. -

Parish Profile for the Parishes of Castle Eaton

South Cotswolds Team Ministry in the Diocese of Gloucester PARISH PROFILE FOR THE PARISHES OF CASTLE EATON, KEMPSFORD with WHELFORD and THE MEYSEYS in the South Cotswolds Team Ministry Cirencester Deanery the Diocese of Gloucester ___________________________________________________________________________ Parish Profile for Castle Eaton, Kempsford & Whelford and The Meyseys Welcome Thank you for taking an interest in this post in the South Cotswolds Team Ministry, caring for the communities of Castle Eaton, Kempsford & Whelford and The Meyseys. You will find three able and enthusiastic PCCs and good supportive people with whom to work. The South Cotswolds Team comprises some 15 parishes and 22 churches stretching from Ampney Crucis, near Cirencester in the west to Lechlade in the east; and from Castle Eaton in the south to Winson in the north. We have four stipendiary clergy and one house-for- duty clergy; two SSM priest colleagues, one of whom has recently moved into Meysey Hampton, a number of Readers - including one based at Kempsford; and supportive retired clergy colleagues. We also have a full-time Youth Worker. We are working hard on what it means to be a ‘Team’ across a large area – the South Cotswolds - and how we use our skills, gifts and opportunities together in building the kingdom of God here in this place. The good news is that members of the Team get on really well together and we enjoy working with each other! We believe in supporting each other and having fun – along with all the other things we have to do. You will be a key member of our Team. -

Gloucestershire County Council Page 1 of 150

Gloucestershire County Council Page 1 of 150 Gloucestershire County Council Page 2 of 150 Abbreviations and Glossary AD Anaerobic Digestion. A process where biodegradable material is encouraged to break down in the absence of oxygen. Material is placed in to an enclosed vessel and in controlled conditions the waste breaks down typically into a digestate, liquor and biogas. AONB Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. ATT Advanced Thermal Treatment. Waste treatment technologies that involve the heating of waste in a reduced oxygen environment to produce a combination of char, synthetic gas and oils that can be used as fuel. These technologies include Pyrolysis and Gasification. Autoclave Autoclave is a form of mechanical heat treatment where waste is subjected to steam under pressure. Generally this process is followed by mechanical sorting and separation of the sterilised waste. The autoclave process produces cleaned glass and metal that is unchanged and that can be recovered. Plastics form mixed lumps/pellets that can be recovered easily and organics form consistent fibres/floc material. BaFO Best and Final Offer. Base The Base Payment is payment calculated on a rate per tonne which is Payment applied to the total tonnage of waste accepted by the contractor in a contract year. BMW Biodegradable Municipal Waste. The component of Municipal Solid Waste capable of being degraded by plants and animals. Biodegradable Municipal Waste includes paper and card, food and garden waste, and a proportion of other wastes, such as textiles. Bottom Ash The ash that arises from a combustion process in a furnace. BRE Building Research Establishment. BREEAM Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method. -

The V.W.H. Hunt

The V.W.H. Hunt 2020 / 2021 Season www.vwh-hunt.co.uk Badminton Horse Trials Wednesday 6th – Sunday 10th May 2020 CROSS COUNTRY SATURDAY 9th MAY The Box Office for advance booking of grandstands, admission and caravan site opens at the beginning of January 2020 Tel: 01454 218375 Fax: 01454 218596 e-mail: [email protected] The Event Office is open year round for all commercial enquiries - hospitality, advertising, promotion opportunities, tradestands. Tel: 01454 218272 Fax: 01454 218596 e-mail: [email protected] We wish the VWH a great season and many more to come. See website for all information www.badminton-horse.co.uk LOCAL PROPERTY EXPERTS Residential • Rural • Farms & Estates • Commercial Ben Knight Anthony Coaker James Walker Will Chanter Savills Rural Management Savills Cirencester London Country Department Savills Rural Agency 07867 786607 07967 555747 07968 550441 07870 999206 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] savills.co.uk Contents Page Page Arkells 12 Oxford Ski Company 4 Badminton Horse Trials Inside Front Oxleaze Farm 34 Bruton Knowles 64 Royal Agricultural University 8 Butler Sherborn 22 Safari Drive 42 DG Equine 40 Savills 1 DWC Turf 6 Sewell Mullings Logie 63 Equi Supplies 46 Stanislas M Yassukovich 16 Forrester Sylvester Mackett 2 Stonewood 48 Geoffs Tyres 18 Sue's Driving School 32-33 Hazlewoods 50 Suzy Waldock 18 IFA Compliance Ltd 56 The Horse Dentist 16 Kernon Countryside Consultants 38 The Hunting Stock Market 28 Knight Frank Back The Orchard Meeting Room 14 Loxley Rural Property Lawyers 24 The Rural Planning Practice 28 Moore Allen & Innocent Inside Back Villa and Alpine Guru 10-11 Neil King Ridgeway Racing 2 Walter Bull and Son 44 NFU Mutual 36 2 Joint Masters Major The Hon. -

Welsh Way Poulton Cirencester Gloucestershire GL7 5SZ 3

2 Item No 01:- 18/00970/FUL Land at Sunhill Welsh Way Poulton Cirencester Gloucestershire GL7 5SZ 3 Item No 01:- Erection 20 dwellings (10 affordable & 10 open market) and associated development at Land At Sunhill Welsh Way Poulton Gloucestershire GL7 5SZ Full Application 18/00970/FUL Applicant: Cotswold Compost Company Ltd Agent: Bruton Knowles Case Officer: Andrew Moody Ward l\/lember(s): Councillor David Fowles Committee Date: 12th September 2018 RECOMMENDATION: REFUSE Main Issues: (a) The principle of development (b) Affordable housing (c) Visual and landscape Impact of the proposal (d) Design (e) Biodiversity (f) Highway safety Reasons for Referral: The application has been referred to Committee by the local Ward Member, Gllr Fowles, for the following reason: - 1want this application to be determined by the committee because both whilst the Sunhill Action Group is against development on this site, the PC and a number of residents believe this Is an Ideal exception site that should be considered for development. Because of the strength of feeling In the community for and against this site, it Is appropriate for both sides to express their views to the Planning Committee. 1. Site Description: The application site is located to the eastern side of Welsh Way In the parish of Poulton, with the southern boundary of the application being located approximately 325 metres to the north of the crossroads at Sunhill. The site has a long established commercial use, most recently for the production of compost, however it is currently unoccupied. The application site extends to the entire site, which includes large areas of hardstanding, with an area of 6.5 hectares and being sub-dlvlded into two areas. -

Ripples MAR 2018 L&F V2016.Qxp 1 LINK Ñ May 07

Ripples MAR 2018 L&F v2016.qxp_1 LINK – May 07 23/02/2018 12:09 Page 1 March 2018 Ripples MAR 2018 L&F v2016.qxp_1 LINK – May 07 23/02/2018 12:09 Page 2 CONTENTS Gut feeling Ripples March About March, many will be regretting New Year’s resolutions broken before they News 4 really got going. Given that a fifth of Brits are ‘on a diet’ at any one time, I’d bet my monthly food bill that failed diets top the score. Home & Garden 13 Creative Arts 19 Aiming to rectify a few niggling ailments, I was recently advised by a dietitian to switch to a diet dictated by my blood type – O negative. The Blood Type Diet was outlined by Councils 24 The New York Times best-selling author Dr Peter D’Adamo. The dietician said that our Rippling Yarns 28 blood type links us to the food groups that our ancestors ate. I am sorry to report that I Learning & Libraries 29 found it so restrictive to be unworkable. Yet others have apparently achieved success with it. Water Park 30 There is an amazing array of diets – Atkins, non-dairy, gluten-free Local History 32 and so on – foisted upon a bamboozled population desperate to Volunteering 34 cope with bulging waistlines. And it’s big business, according to Sport 36 Professor Tim Spector who claims there are ‘well over 30,000 books available, with their own websites and merchandising, Food & Drink 38 promoting diet regimes and supplements ranging from the Business 42 sensible to the dangerous’. -

![Pageflex Server [Document: A9838711 00001]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8244/pageflex-server-document-a9838711-00001-5068244.webp)

Pageflex Server [Document: A9838711 00001]

Sunhill Close, Fairford, Gloucestershire, GL7 4LY Four double bedrooms | Countryside views Sitting room with double doors into the garden | Chain free Large kitchen/dining room | EPC C £595,000 Cirencester Cheltenham Fairford Faringdon Leckhampton London Nailsworth Stroud Tetbury Sunhill Close, Fairford, Gloucestershire, GL7 4LY 4 Bedrooms 2 Bathrooms 3 Receptions A beautifully presented and very impressive spacious and there is also a useful utility room and a study overlooking the attractive four bedroom detached home, built approximately front. ten years ago to a very high standard and specification, providing a very pleasant and comfortable home. An American oak staircase leads to the first floor. The master bedroom is a particularly impressive room with an excellent The property is attractively situated on the outskirts of a well- aspect across open countryside, and there are large regarded market town, within easy reach of local facilities wardrobes and an en-suite bathroom fitted to an excellent and amenities, yet also being close to open countryside and standard. backing onto fields. There are three further well-proportioned bedrooms with The accommodation is approached into a welcoming and the rear bedrooms enjoying the views across the garden and spacious reception hall. There is a cloakroom and a large fields, and a family bathroom has a bath and a separate under-stairs cupboard. The dual aspect sitting room is an shower. excellent room with a fireplace and gas wood burner style stove and French doors onto the private rear garden. The Outside, the property is approached via a small gate and kitchen/dining room is a very attractive open plan room with front dry stone walling. -

Hampton Fields Farm Meysey Hampton • Cirencester • Gloucestershire

HAMPTON FIELDS FARM MEYSEY HAMPTON • CIRENCESTER • GLOUCESTERSHIRE HAMPTON FIELDS FARM MEYSEY HAMPTON • CIRENCESTER GLOUCESTERSHIRE Meysey Hampton 1 mile • Cirencester 6 miles • Fairford 2½ miles Swindon (trains to London Paddington 55 mins) 14 miles M5 (J11A) 15 miles • M4 (J15) 16 miles • Cheltenham 20 miles • Oxford 32 miles (Distances and times approximate) A beautifully positioned Cotswold country property together with mature gardens and paddock land Reception hall • Drawing room • Sitting room • Dining room • Conservatory Kitchen/ breakfast room • Boot room • Utility room • WC • Cellar Master bedroom with en-suite bathroom • Four further bedrooms Three further bathrooms Double garage • Loft storage Stables • Tack room • Machinery store In all about 8.25 acres Approximately 35.25 acres available by separate negotiation Savills Cirencester 1 Castle Street, Market Place, Cirencester GL7 1QD Contact: Anthony Coaker [email protected] 01285 627550 www.savills.co.uk SITUATION Hampton Fields is a particularly private but not isolated country house, approached off a country lane and only about a mile from Meysey Hampton. Here there is an active church, highly regarded primary school, village hall, playing fields and on the green, the Mason’s Arms. The nearest market town is Fairford, which is approximately 2 miles away and offers a good selection of every day amenities and facilities including a cottage hospital, doctors surgery, a number of public houses, post office, butchers, Co-op, two churches and a number of popular clubs and societies. Cirencester, widely recognised as the ‘capital of the Cotswolds’ provides a more comprehensive range of shops and services as well as restaurants and larger supermarkets including Waitrose and Tesco.