Robert A. Trias (1923-1989) ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snapkick Dojo Student Newsletter

Snapkick Dojo student newsletter “The ultimate aim of karate lies not in victory nor defeat, but in the perfection of the character of its participants ” ― Gichin Funakoshi “Protect your enthusiasm from the negativity of others.” ~ H. Jackson Brown, Jr. Sensei Gichin Funakoshi - Father of Modern Day Karate O’Sensei Gichin Funakoshi is known as the Father of One was that he adapted the training methods so Modern Day Karate and is probably the best known name that they could be more easily practiced by everybody, in karate history. regardless of age, ability or sex. He was born in the city of Shuri on the island of He also made karate more accessible to the Okinawa in 1868 and by the age of 11, Funakoshi was Japanese by changing the meaning of the word ‘Kara’. training with the great Okinawan teachers Anko Itosu and Originally, the words kara and te meant ‘Chinese’ and Yasutsune Azato. ‘hand.’ However, in Japanese the characters used for At this time it was illegal to learn martial arts, though kara could also mean ‘empty’ in Japanese. As this fitted that did not stop him and many others practicing in secret. the style so well and since karate had developed to be Around the turn of the century the art came out into the very different from the Chinese styles, ‘empty hand’ open and began to be taught in public schools, thanks became the new meaning of the word. largely to the efforts of Anko Itosu. Amongst his more prominent beliefs was By the time Funakoshi was an adult he excelled in Funakoshi’s conviction that the best martial arts karate, so much so that when the Crown Prince of Japan, exponents should be so confident that they had nothing Hirohito, visited Okinawa, Funakoshi was chosen to to prove about their fighting prowess. -

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States Copyright 2006 Rob Redmond. All Rights Reserved. No part of this may be reproduced for for any purpose, commercial or non-profit, without the express, written permission of the author. Listed with the US Library of Congress US Copyright Office Registration #TXu-1-167-868 Published by digital means by Rob Redmond PO BOX 41 Holly Springs, GA 30142 Second Edition, 2006 2 Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States In Gratitude The Karate Widow, my beautiful and apparently endlessly patient wife – Lorna. Thanks, Kevin Hawley, for saying, “You’re a writer, so write!” Thanks to the man who opened my eyes to Karate other than Shotokan – Rob Alvelais. Thanks to the wise man who named me 24 Fighting Chickens and listens to me complain – Gerald Bush. Thanks to my training buddy – Bob Greico. Thanks to John Cheetham, for publishing my articles in Shotokan Karate Magazine. Thanks to Mark Groenewold, for support, encouragement, and for taking the forums off my hands. And also thanks to the original Secret Order of the ^v^, without whom this content would never have been compiled: Roberto A. Alvelais, Gerald H. Bush IV, Malcolm Diamond, Lester Ingber, Shawn Jefferson, Peter C. Jensen, Jon Keeling, Michael Lamertz, Sorin Lemnariu, Scott Lippacher, Roshan Mamarvar, David Manise, Rolland Mueller, Chris Parsons, Elmar Schmeisser, Steven K. Shapiro, Bradley Webb, George Weller, and George Winter. And thanks to the fans of 24FC who’ve been reading my work all of these years and for some reason keep coming back. -

The Essence of Goju Ryu - Vol 1 by Richard Barrett, Garry Lever

The Essence of Goju Ryu - Vol 1 By Richard Barrett, Garry Lever Recommended by: Ryan Parker, The Essence of Goju Ryu Vol II By Garry Lever, Richard Barrett Recommended by: Ryan Parker, The Art of Hojo Undo: Power Training for Traditional Karate by Michael Clarke Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Unante by John Sells Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Okinawan Karate by Mark Bishop Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Noah Legel Okinawan Weaponry, Hidden Methods, Ancient Myths of Kobudo & Te by Mark Bishop Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Noah Legel The Secret Royal Martial Arts Of Ryukyu by Kanenori Sakon Matsuo Recommended by: Ryan Parker, History and Traditions of Okinawan Karate by Tetsuhiro Hokama Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Noah Legel The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do by Shoshin Nagamine Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Noah Legel Okinawa No Bushi No Te The Hands Of The Okinawan Bushi by Mr Ronald L Lindsey Recommended by Ryan Parker, Okinawan Kempo by Choki Motobu Recommended by Ryan Parker, My Art of Karate by Motobu Choki Recommended by: Ryan Parker, The History of Karate: Okinawan Goju-Ryu by Morio Higaonna and D. McIntyre Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Bubishi by Patrick McCarthy Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Noah Legel To-te Jitsu by Gichin Funakoshi Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Zen Kobudo: The Mysteries of Okinawan Weaponry and Te by Bishop, Mark Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Okinawan Goju-Ryu: Fundamentals of Shorei-Kan Karate by Seikichi Toguchi Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Okinawan Goju-Ryu II: Advanced Techniques of Shorei-Kan Karate by Seikichi Toguchi Recommended by: Ryan Parker, Okinawa Traditional Old Martial Arts: Kobudo, Karate by Nakamoto Masahiro Recommended by: Noah Legel, My Journey with the Grandmaster by Bill Hayes Recommended by: Noah Legel, Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts by Donn Draeger and Robert Smith Recommended by: Noah Legel, Okinawa: The History of an Island People by George Kerr Recommended by: Noah Legel, Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts: Koryu Uchinadi Vol. -

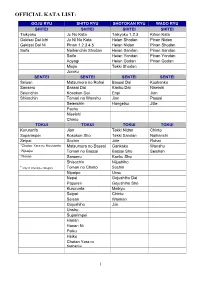

Official Kata List

OFFICIAL KATA LIST: GOJU RYU SHITO RYU SHOTOKAN RYU WADO RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Taikyoku Ju No Kata Taikyoku 1.2.3 Kihon Kata Gekisai Dai Ichi Ju Ni No Kata Heian Shodan Pinan Nidan Gekisai Dai Ni Pinan 1.2.3.4.5 Heian Nidan Pinan Shodan Saifa Naihanchin Shodan Heian Sandan Pinan Sandan Saifa Heian Yondan Pinan Yondan Aoyagi Heian Godan Pinan Godan Miojio Tekki Shodan Juroku SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Seisan Matsumora no Rohai Bassai Dai Kushanku Sanseru Bassai Dai Kanku Dai Niseishi Seiunchin Kosokun Dai Enpi Jion Shisochin Tomari no Wanshu Jion Passai Seienchin Hangetsu Jitte Pachu Niseishi Chinto TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI Kururunfa Jion Tekki Nidan Chinto Suparimpei Kosokun Sho Tekki Sandan Naihanchi Seipai Sochin Jitte Rohai *Chatan Yara no Kushanku Matsumura no Bassai Gankaku Wanshu *Nipaipo Tomari no Bassai Bassai Sho Seishan *Hanan Sanseru Kanku Sho Shisochin Nijushiho * only in interstyle category Tomari no Chinto Sochin Nipaipo Unsu Nepai Gojushiho Dai Papuren Gojushiho Sho Kururunfa Meikyo Seipai Chinte Seisan Wankan Gojushiho Jiin Unshu Suparimpei Hanan Hanan Ni Paiku Heiku Chatan Yara no Kushanku 1 OFFICIAL LIST OF SOME RENGOKAI STYLES: GOJU SHORIN RYU SHORIN RYU UECHI RYU USA KYUDOKAN OKINAWA TE SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Taikyoku Jodan Fukiu Gata Ichi Fugyu Shodan Kanshiva Taikyoku Chiudan Fukiu Gata Ni Fugyu Nidan Kanshu Taikyoku Gedan Pinan Nidan Pinan Nidan Sechin Taikyoku Consolidale Ichi Pinan Shodan Pinan Shodan Seryu Taikyoku Consolidale Ni Pinan Sandan Pinan Sandan SENTEI Taikyoku Consolidale San Pinan -

Purple (6Th Kyu) to Green Belt (5Th Kyu)

Purple (6th Kyu) to Green Belt (5th Kyu) Stripe Guidelines WHITE 25 Jumping Jacks, 15 Burpees, 20 Karate Leg Stretches, 40 Mountain Climbers, 20 Sit- ups, 20 Push-ups, Jog in place for 2 minutes GREEN Double Block (Middle/Low), Elbow Block, Back fist, Chase Punch., & Spinning Back BLUE Two Hand Front Choke Defense Before & After YELLOW Purple Belt Ippon 1 & 2; Test Sparring for 2 minutes (No Contact) BLACK Pinan Sandan (P), Pinan Shodan RED Leadership: Commitment & Responsibility ORANGE Optional - Special Projects, Advanced Activities Bonus Kata - Ananku Sho (Matsubayashi) Basic Test Requirements Exercises Basics Purple Belt Ippon 1 & 2 Pinan Sandan (Primary), Pinan Shodan Two Hand Front Choke Defense Just Before & Immediately After Test Sparring Orange Stripe Kata Ananku Sho (Matsubayashi) Details: All Ippon drills alternate both sides, left and right. Purple Belt Ippon 1 Attacker: Right Step & Right High Lunge Punch. Defender: Left Step Forward into Walking Stance & Left Open Hand High Block. Right Spear Hand Strike/Chop to Throat/Eyes. Purple Belt Ippon 2 Attacker: Right Step & Right Middle Lunge Punch. Defender: Left slide backward and to the outside of your opponent 45 ° into Right Cat Stance & Right Shuto Block. Right Grab & Right Side Kick to Ribs/Armpit. Leadership (copy and complete the form in back of booklet to earn your stripe) Commitment – is when you decide to do whatever it takes. Responsibility – is taking full responsibility for your actions. Family Martial Arts Academy - Senior Belt Test Requirements (White-Candidate) © ASKA/FMAA 2013 [Version 01/26/2015_mv] . -

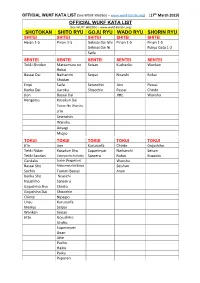

Official Wukf Kata List Shotokan Shito Ryu Goju

OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) [17th March 2019] OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) SHOTOKAN SHITO RYU GOJU RYU WADO RYU SHORIN RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Heian 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ichi Pinan 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ni Fukyu Gata 1-2 Saifa SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Tekki Shodan Matsumura no Seisan Kushanku Wankan Rohai Bassai Dai Naihanchi Seipai Niseishi Rohai Shodan Empi Saifa Seiunchin Jion Passai Kanku Dai Jiuroku Shisochin Passai Chinto Jion Bassai Dai Jitte Wanshu Hangetsu Kosokun Dai Tomari No Wanshu Ji'in Seienchin Wanshu Aoyagi Miojio TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI Ji'in Jion Kururunfa Chinto Gojushiho Tekki Nidan Kosokun Sho Suparimpai Naihanchi Seisan Tekki Sandan Ciatanyara No Kushanku Sanseru Rohai Kusanku Gankaku Sochin (Aragaki ha) Wanshu Bassai Sho Matsumura No Bassai Seishan Sochin Tomari Bassai Anan Kanku Sho Niseichi Nijushiho Sanseiru Gojushiho Sho Chinto Gojushiho Dai Shisochin Chinte Nipaipo Unsu Kururunfa Meikyo Seipai Wankan Seisan Jitte Gojushiho Unshu Suparimpei Anan Jitte Pacho Haiku Paiku Papuren KATA LIST - WUKF COMPETITION UECHI RYU KYOKUSHINKAI BUDOKAN GOSOKU RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Kanshiva Pinan 1-5 Heian 1-5 Kihon Ichi No Kata Sechin Kihon Yon No Kata Kanshu Kime Ni No Kata Seiryu (Kiyohide) Ryu No Kata Uke No Kata SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Sesan Geksai Dai Empi Ni No Kata Kanchin Tsuki No Kata Tekki 1-2 Kime No Kata Sanseryu Yantsu Bassai Dai Gosoku Tensho Kanku Dai Gosoku Yondan Saifa Jion Sanchin no -

2020 AAU Karate Handbook – General Rules

2020 AAU Karate Handbook – General Rules SECTION 1. AAU/USA KARATE RULES FOR COMPETITION ARTICLE 1. GENERAL GUIDELINE • The rules of competition for all tournaments, matches, and competitions licensed by AAU/USA KARATE shall be as stated herein. These rules shall be used in all licensed competitions, without modification or amendment for events which qualify athletes for further competition. • These rules are based upon the rules adopted by the different International Federations (IF) for competition. These rules, or any part thereof, may be modified or amended by AAU/USA KARATE National Executive Committee at any time. Whenever a specific rule is in conflict with a more general rule, the specific rule shall take precedence. • International Federation rules without modification shall be used in team selection procedure. Modifications without AAU/USA Karate Committee approval may not be made for any competition to select competitors for the AAU/USA National Karate Team. • Under special circumstances exceptions to these rules may be made with the prior approval of the National Executive Committee, with consultation with the Referee Council. • All exceptions to these rules, National competition or International Team selection, in whole or part must be approved by the AAU/USA Karate Executive Committee. ARTICLE 2. COMPETITION AREA • The competition area must be flat and devoid of hazard. The area shall be a matted square of suitable size. Where mats are not used, the competition area may be defined by marking the boundaries with colored tape of appropriate thickness. The area may be elevated to a height of up to one meter above floor level. -

Shorinji-Ryu Renshinkan Karatedo

Shorinji-ryu Renshinkan Karatedo 5 kyu Kihon Yakusokukumite -shiko tsuki 1-5 -kuukan tsuki -sonoba maegeri -gedanbarai-sokutogeri Zenshin-kotai -shutouke -jodanuke -gedanbarai-chudan gyakutsuki -chudanuke-chudan gyakutsuki -enpi ate -shomengeri -shokutogeri -Kenshuho migi/hidari Shorinji-ryu Renshinkan Karatedo 4 kyu Kihon Yakusokukumite -shiko tsuki 1-10 -kuukan tsuki -sonobamaegeri Kooboo tsuki kaeshi -gedanbarai-sokutogeri 1-2 -gedanbarai-mawashigeri Zenshin-kotai Kata Seisan -Shutouke -jodanuke -gedanbarai-chudan gyakutsuki -chudanuke-chudan gyakutsuki -enpi ate -shomengeri -ushirogeri -shokutogeri -Kenshuho migi/hidari Shorinji-ryu Renshinkan Karatedo 3 kyu Kihon Yakusokukumite -shiko tsuki 1-20 -kuukan tsuki -sonoba maegeri Kooboo tsuki kaeshi -gedanbarai-sokutogeri 1-4 -gedanbarai-mawashigeri Zenshin-kotai Nagewaza 1-2 -shutouke -jodanuke Kata -gedanbarai shudan gyakutsuki Seisan -chudanuke chudan gyakutsuki Ananku -enpiate -uraken uchi -nagashi tsuki -razen shuto uchi -shomengeri -ushirogeri -uramawashigeri -sokutogeri -kenshuho migi/hidari Shorinji-ryu Renshinkan Karatedo 2 kyu Kihon Yakusokukumite -shikotsuki 1-30 -kuukantsuki -sonoba maegeri Kooboo tsuki kaeshi -gedanbarai-sokutogeri 1-4 -gedanbarai-mawashigeri Zenshin-kotai Nagewaza 1-5 -shutouke -jodanuke Kata -gedanbarai-chudan gyakutsuki Seisan -chudanuke-chudan gyakutsuki Ananku -enpiate Wanshu -uraken uchi -razen shuto uchi Tankensabaki -nagashi tsuki 1-2 -shuto uchi -shomengeri -ushiromawashigeri -ushirogeri -uramawashigeri -sokutogeri Jiyu kumite -kenshuho migi/hidari -

Ueshiro Okinawan Karate Family Club (Est

Ueshiro Okinawan Karate Family Club (Est. 2004) Kyoshi Matt Kaplan, Denshi Shihan, Hachi-Dan Welcome to our Karate Family Club! To help you get started, below are our dojo guidelines and an introduction to Japanese terminology we often use in our classes. New white belts are invited to simply follow along and copy senior students to the best of your ability. Our Dojo Rules "Fundamental to Shorin-ryu is the observance by practitioners of courtesy and mutual respect." — Hanshi Robert Scaglione 1. Always show courtesy to all. 2. Address your instructor as sensei or sempai. 3. Bow to the instructor/sensei when entering or leaving the dojo. 4. When a black belt instructor of sandan rank or above enters or leaves the deck in gi (uniform) for the first time, the senior student stops the activity on the deck and calls the other students to attention. 5. Prohibited in the dojo: • No wearing jewelry or other ornaments on the deck during class • No food or drink allowed on the deck • No talking or laughing while class is in session • No profanity 6. Keep your gi clean. 7. Keep your fingernails and toenails short. 8. Refrain from misusing your karate knowledge. 9. Do not leave the deck while class is in session without the instructor’s permission. 10. Students should bow to each other before and after each practice. 11. Strive to promote the true spirit of the martial arts by: • Character - mental development • Health - physical development • Skill - proficiency in karate • Respect - courtesy to others • Humility - be aware of your shortcomings 12. -

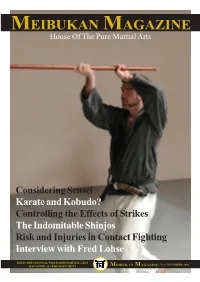

Of Okinawan Uechi-Ryu Karate

MEIBUKAN MAGAZINE House Of The Pure Martial Arts Considering Sensei Karate and Kobudo? Controlling the Effects of Strikes The Indomitable Shinjos Risk and Injuries in Contact Fighting Interview with Fred Lohse Fred Lohse with bo. Courtesy of Jim Baab. THE INTERNATIONAL WEB BASED MARTIAL ARTS No 8 DECEMBER 2006 MAGAZINE AS A PDF DOCUMENT MEIBUKAN MAGAZINE House of the Pure Martial Arts WWW.MEIBUKANMAGAZINE.ORG No 8 DECEMBER 2006 MEIBUKAN MAGAZINE House of the Pure Martial Arts No 8 DECEMBER 2006 MISSION STATEMENT Column 2 Meibukan Magazine is an initiative of founders Lex Opdam and Mark Hemels. Aim of this web based We want your help! magazine is to spread the knowledge and spirit of the martial arts. In a non profitable manner Meibukan Magazine draws attention to the historical, spiritual Feature 2 and technical background of the oriental martial arts. Starting point are the teachings of Okinawan karate- Karate and Kobudo? do. As ‘House of the Pure Martial Arts’, however, Fred Lohse takes us on a journey through the history of karate and kobudo in Meibukan Magazine offers a home to the various au- thentic martial arts traditions. an effort to explain why the two are actually inseparable. FORMAT Interview 9 Meibukan Magazine is published several times a year Interview with Fred Lohse in an electronical format with an attractive mix of subjects and styles. Each issue of at least twelve Lex Opdam interviews Goju-ryu and Matayoshi kobudo practitioner Fred pages is published as pdf-file for easy printing. Published Lohse. editions remain archived on-line. Readers of the webzine are enthousiasts and practi- tioners of the spirit of the martial arts world wide. -

Student Training Guide

Volume 1 MID-ATLANTIC KARATE SCHOOLS, INC. The Last Teachings by Chojun Miyagi Do not be struck by others. Do not strike others. The principle is the peace without incident. STUDENT TRAINING GUIDE STUDENT TRAINING GUIDE Handbook for New Students Mid-Atlantic Karate Schools, Inc. 50 Coffman Drive • Collinsville, VA 24078 Phone 540.647.5425 Welcome to the World of Martial Arts ________________________ 2 A Brief History of Goju Ryu Karate-Do ___________________ 3 Miyagi Chojun Sensei ___________4 Higaonna Kanryo Sensei ________6 History of USA Goju Ryu Association ____________________7 The Student Creed ____________ 8 Student Conduct _____________ 10 General Guidelines ____________11 Class Guidelines ______________11 Restrooms and Changing Rooms_12 Terminology ________________ 13 Counting_____________________13 Special Terminology of Karate __13 Commands ___________________13 Techniques ___________________13 Class Schedule ______________ 14 The Board of Examiners________15 The National Black Belt Club (NBBC)______________________15 Assigned Classes ______________15 Missing a Class _______________15 Extended Leave of Absence _____16 Promotion Requirements ______ 17 Ranked Student’s ________________17 Promotion Requirements (Kata) ____17 Assistant Instructor ______________17 Promotion Requirements (Kata) ____17 Instructor ______________________17 Promotion Requirements (Kata) ____17 Second Degree Black Belt’s _______17 Requirements (Kata) _____________17 Junior Ranger Promotion Requirements ______________________________18 THE STUDENT’S HANDBOOK Introduction i THE STUDENT’S HANDBOOK Welcome to the World of Martial Arts You can get anything in life you want if you help enough other people get what they want. – Zig Ziglar You have entered the world of the Martial Arts. Many mysteries surround the oriental KEY culture. One of the most fascinating is the Martial Arts or “the art of war”. It is the Valuable information goal of this school to give you the absolute best in training, knowledge, application and understanding of the art of Karate. -

(2014): the Way of the Grandmaster: Rev. Dr. Donald Miskel. ICMAUA: 282 P

The Way of the Grandmaster: Rev. Dr. Donald Miskel Donald Miskel International Combat Martial Arts Unions Association www.icmaua.com 2014 UDC: 796.8/ The Way of the Grandmaster: Rev. Dr. Donald Miskel. ICMAUA, 2014: 282 p. www.icmaua.com _____________________________________________________________________________________ Recommended citation: Donald Miskel (2014): The Way of the Grandmaster: Rev. Dr. Donald Miskel. ICMAUA: 282 p. www.icmaua.com Editor: Dr. Mihails Pupinsh, ICMAUA Disclaimer The full responsibility for the published material, text, photos of third persons, and pictures belongs to the author, Rev. Dr. Donald Miskel. The logos of and documents from other organizations were sent by the author and are used only as illustrations. The publisher, editor, and the ICMAUA disclaim responsibility for any liability, injuries, or damages. Address for correspondence: [email protected] Text, pictures © Rev. Dr. Donald Miskel. All rights reserved Issue, design © ICMAUA. All rights reserved 2 The Way of the Grandmaster: Rev. Dr. Donald Miskel. ICMAUA, 2014: 282 p. www.icmaua.com _____________________________________________________________________________________ On the books series The International Combat Martial Arts Unions Association (ICMAUA, www.icmaua.com) publishes the book series “The Way of the Grandmaster” authors’ (the Masters and Grandmasters) works on all aspects of Grandmasters and Masters Martial Arts research, history, trainings, journey, teaching, education, and philosophy, personals life, and real self-defense cases. Dear Grandmasters! Please, send us your own written author work on your Martial Arts Way for publishing! The Books series “The Way of the Grandmaster” will be published in a PDF format "as is written by author (the Grandmaster)", without any changes (also grammatical or stylistic) in the text.