Singing the Praises Mid 220220

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kristianstads Vattenrike Biosphere Reserve, Periodic Review 2005-2015

This Periodic Review can also be downloaded at www.vattenriket.kristianstad.se/unesco/. Title: Kristianstads Vattenrike Biosphere Reserve. Periodic Review 2005-2015 Authors: This review is produced by the Biosphere Office, Kristianstads kommun: Carina Wettemark, Johanna Källén, Åsa Pearce, Karin Magntorn, Jonas Dahl, Hans Cronert; Karin Hernborg and Ebba Trolle. In addition a large number of people have contributed directly and indirectly. Cover photo: Patrik Olofsson/N Maps: Stadsbyggnadskontoret Kristianstads kommun PERIODIC REVIEW FOR BIOSPHERE RESERVE INTRODUCTION The UNESCO General Conference, at its 28th session, adopted Resolution 28 C/2.4 on the Statutory Framework of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves. This text defines in particular the criteria for an area to be qualified for designation as a biosphere reserve (Article 4). In addition, Article 9 foresees a periodic review every ten years The periodic review is based on a report prepared by the relevant authority, on the basis of the criteria of Article 4. The periodic review must be submitted by the national MAB Committee to the MAB Secretariat in Paris. The text of the Statutory Framework is presented in the third annex. The form which follows is provided to help States prepare their national reports in accordance with Article 9 and to update the Secretariat's information on the biosphere reserve concerned. This report should enable the International Coordinating Council (ICC) of the MAB Programme to review how each biosphere reserve is fulfilling the criteria of Article 4 of the Statutory Framework and, in particular, the three functions: conservation, development and support. It should be noted that it is requested, in the last part of the form (Criteria and Progress Made), that an indication be given of how the biosphere reserve fulfils each of these criteria. -

Coleoptera and Lepidoptera (Insecta) Diversity in the Central Part of Sredna Gora Mountains (Bulgaria)

BULLETIN OF THE ENTOMOLOGICALENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF MALTAMALTA (2019) Vol. 10 : 75–95 DOI: 10.17387/BULLENTSOCMALTA.2019.09 Coleoptera and Lepidoptera (Insecta) diversity in the central part of Sredna Gora Mountains (Bulgaria) Rumyana KOSTOVA1*, Rostislav BEKCHIEV2 & Stoyan BESHKOV2 ABSTRACT.ABSTRACT. Despite the proximity of Sredna Gora Mountains to Sofia, the insect assemblages of this region are poorly studied. As a result of two studies carried out as a part of an Environmental Impact Assessment in the Natura 2000 Protected Areas: Sredna Gora and Popintsi, a rich diversity of insects was discovered, with 107 saproxylic and epigeobiont Coleoptera species and 355 Lepidoptera species recorded. This research was conducted during a short one-season field study in the surrounding areas of the town of Panagyurishte and Oborishte Village. Special attention was paid to protected species and their conservation status. Of the Coleoptera recorded, 22 species were of conservation significance. Forty-five Lepidoptera species of conservation importance were also recorded. KEY WORDS.WORDS. Saproxylic beetles, epigeobiont beetles, Macrolepidoptera, Natura 2000 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION The Sredna Gora Mountains are situated in the central part of Bulgaria, parallel to the Stara Planina Mountains The Sredna chain. Gora TheyMountains are insufficiently are situated instudied the central with partregard of toBulgaria, their invertebrate parallel to theassemblages. Stara Planina Mountains chain. They are insufficiently studied with regard to their invertebrate assemblages. There is lack of information about the beetles from Sredna Gora Mountains in the region of the Panagyurishte There is lack townof information and Oborishte about village. the beetles Most offrom the Srednaprevious Gora data Mountains is old and foundin the inregion catalogues, of the mentioningPanagyurishte the town mountain and Oborishte without distinct village. -

Globalna Strategija Ohranjanja Rastlinskih

GLOBALNA STRATEGIJA OHRANJANJA RASTLINSKIH VRST (TOČKA 8) UNIVERSITY BOTANIC GARDENS LJUBLJANA AND GSPC TARGET 8 HORTUS BOTANICUS UNIVERSITATIS LABACENSIS, SLOVENIA INDEX SEMINUM ANNO 2017 COLLECTORUM GLOBALNA STRATEGIJA OHRANJANJA RASTLINSKIH VRST (TOČKA 8) UNIVERSITY BOTANIC GARDENS LJUBLJANA AND GSPC TARGET 8 Recenzenti / Reviewers: Dr. sc. Sanja Kovačić, stručna savjetnica Botanički vrt Biološkog odsjeka Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet, Sveučilište u Zagrebu muz. svet./ museum councilor/ dr. Nada Praprotnik Naslovnica / Front cover: Semeska banka / Seed bank Foto / Photo: J. Bavcon Foto / Photo: Jože Bavcon, Blanka Ravnjak Urednika / Editors: Jože Bavcon, Blanka Ravnjak Tehnični urednik / Tehnical editor: D. Bavcon Prevod / Translation: GRENS-TIM d.o.o. Elektronska izdaja / E-version Leto izdaje / Year of publication: 2018 Kraj izdaje / Place of publication: Ljubljana Izdal / Published by: Botanični vrt, Oddelek za biologijo, Biotehniška fakulteta UL Ižanska cesta 15, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenija tel.: +386(0) 1 427-12-80, www.botanicni-vrt.si, [email protected] Zanj: znan. svet. dr. Jože Bavcon Botanični vrt je del mreže raziskovalnih infrastrukturnih centrov © Botanični vrt Univerze v Ljubljani / University Botanic Gardens Ljubljana ----------------------------------- Kataložni zapis o publikaciji (CIP) pripravili v Narodni in univerzitetni knjižnici v Ljubljani COBISS.SI-ID=297076224 ISBN 978-961-6822-51-0 (pdf) ----------------------------------- 1 Kazalo / Index Globalna strategija ohranjanja rastlinskih vrst (točka 8) -

List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007) For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-bap/ List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007) A list of the UK BAP priority terrestrial invertebrate species, divided by taxonomic group into: Insects, Arachnids, Molluscs and Other invertebrates (Crustaceans, Worms, Cnidaria, Bryozoans, Millipedes, Centipedes), is provided in the tables below. The list was created between 1995 and 1999, and subsequently updated in response to the Species and Habitats Review Report published in 2007. The table also provides details of the species' occurrences in the four UK countries, and describes whether the species was an 'original' species (on the original list created between 1995 and 1999), or was added following the 2007 review. All original species were provided with Species Action Plans (SAPs), species statements, or are included within grouped plans or statements, whereas there are no published plans for the species added in 2007. Scientific names and commonly used synonyms derive from the Nameserver facility of the UK Species Dictionary, which is managed by the Natural History Museum. Insects Scientific name Common Taxon England Scotland Wales Northern Original UK name Ireland BAP species? Acosmetia caliginosa Reddish Buff moth Y N Yes – SAP Acronicta psi Grey Dagger moth Y Y Y Y Acronicta rumicis Knot Grass moth Y Y N Y Adscita statices The Forester moth Y Y Y Y Aeshna isosceles -

(Amsel, 1954) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae, Phycitinae) – a New Species for the Croatian Pyraloid Moth Fauna, with an Updated Checklist

NAT. CROAT. VOL. 30 No 1 37–52 ZAGREB July 31, 2021 original scientific paper / izvorni znanstveni rad DOI 10.20302/NC.2021.30.4 PSOROSA MEDITERRANELLA (AMSEL, 1954) (LEPIDOPTERA: PYRALIDAE, PHYCITINAE) – A NEW SPECIES FOR THE CROATIAN PYRALOID MOTH FAUNA, WITH AN UPDATED CHECKLIST DANIJELA GUMHALTER Azuritweg 2, 70619 Stuttgart, Germany (e-mail: [email protected]) Gumhalter, D.: Psorosa mediterranella (Amsel, 1954) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae, Phycitinae) – a new species for the Croatian pyraloid moth fauna, with an updated checklist. Nat. Croat., Vol. 30, No. 1, 37–52, 2021, Zagreb. From 2016 to 2020 numerous surveys were undertaken to improve the knowledge of the pyraloid moth fauna of Biokovo Nature Park. On August 27th, 2020 one specimen of Psorosa mediterranella (Amsel, 1954) from the family Pyralidae was collected on a small meadow (985 m a.s.l.) on Mt Biok- ovo. In this paper, the first data about the occurrence of this species in Croatia are presented. The previ- ous mention in the literature for Croatia was considered to be a misidentification of the past and has thus not been included in the checklist of Croatian pyraloid moth species. P. mediterranella was recorded for the first time in Croatia in recent investigations and, after other additions to the checklist have been counted, is the 396th species in the Croatian pyraloid moth fauna. An overview of the overall pyraloid moth fauna of Croatia is given in the updated species list. Keywords: Psorosa mediterranella, Pyraloidea, Pyralidae, fauna, Biokovo, Croatia Gumhalter, D.: Psorosa mediterranella (Amsel, 1954) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae, Phycitinae) – nova vrsta u hrvatskoj fauni Pyraloidea, s nadopunjenim popisom vrsta. -

ISOLATION, CHARACTERISATION AND/OR EVALUATION of PLANT EXTRACTS for ANTICANCER POTENTIAL KARUPPIAH PILLAI MANOHARAN (M.Sc., M.Ph

ISOLATION, CHARACTERISATION AND/OR EVALUATION OF PLANT EXTRACTS FOR ANTICANCER POTENTIAL KARUPPIAH PILLAI MANOHARAN (M.Sc., M.Phil., B.Ed.,) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2006 Acknowledgements I wish to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors, Associate Prof. Yang Dai Wen and Associate Prof. Tan, Benny Kwong Huat for their advice, suggestions, constructive criticisms, critical comments and constant guidance throughout the course my study. I am very thankful to Asst. Prof. Henry, Mok Yu-Keung; his supervisor-like role throughout my research work is greatly appreciated. I am very grateful to Prof. Sim Keng Yeow for his help, support and guidance at the beginning of this course of study. I would like to thank all the technical staffs of Departments of Chemistry and Pharmacology for their superb technical assistance. My sincere thanks are due to Ms. Annie Hsu for her technical assistance at the traditional medicine and natural product research laboratory, Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine. I would like to thank Dr. Fan Sing Jong, NMR Manager for his help in the structure elucidation. I would like to thank Associate Prof. Hugh Tan Tiang Wah and Chua Keng Soon, Senior Laboratory Officer (RMBR), Herbarium, for the identification of plant materials, Eugenia grandis and Fagraea fragrans. I am very grateful to the former head Prof. Lee Hian Kee and the present head Prof. Hor Tzi Sum, Andy, Department of Chemistry for facilitating requests and approvals during the period of my study. My appreciation also goes to all my friends. -

January Review of Butterfly, Moth and Other Natural History Sightings 2019

Review of butterfly, moth and other natural history sightings 2019 January January started dry and settled but mostly cloudy with high pressure dominant, and it remained generally dry and often mild during the first half of the month. The second half became markedly cooler with overnight frosts and the last week saw a little precipitation, some which was occasionally wintry. With the mild weather continuing from December 2018 there were a small number of migrant moths noted in January, comprising a Dark Sword-grass at Seabrook on the 5th, a Silver Y there on the 13th and 2 Plutella xylostella (Diamond-back Moths) there on the 15th, whilst a very unseasonal Dark Arches at Hythe on the 4th may have been of immigrant origin. Dark Sword-grass at Seabrook (Paul Howe) Dark Arches at Hythe (Ian Roberts) More typical species involved Epiphyas postvittana (Light Brown Apple Moth), Satellite, Mottled Umber, Winter Moth, Chestnut, Spring Usher and Early Moth. Early Moth at Seabrook (Paul Howe) Spring Usher at Seabrook (Paul Howe) The only butterfly noted was a Red Admiral at Nickolls Quarry on the 1st but the mild weather encouraged single Buff-tailed Bumblebees to appear at Seabrook on the 7th and Mill Point on the 8th, whilst a Minotaur Beetle was attracted to light at Seabrook on the 6th. A Common Seal and two Grey Seals were noted regularly off Folkestone, whilst at Hare was seen near Botolph’s Bridge on the 1st and a Mink was noted there on the 17th. February After a cold start to the month it was generally mild from the 5th onwards. -

Rivalry and Revenge Costantinopoli 1786: La Congiura E La Beffa (Constantinople 1786: the Conspiracy and the Hoax) by Paolo Mazzarello Bollati Boringhieri: 2004

books and arts in writing. With its clear and accessible style, the book could be shared with young readers, who might be less susceptible than earlier generations to narratives of romantic INDEX, FIRENZE self-sacrifice, and more intrigued by the psychological portrait of a complicated and accomplished woman scientist. ■ Susan Lindee is in the Department of History and Sociology of Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6304, USA. Rivalry and revenge Costantinopoli 1786: la congiura e la beffa (Constantinople 1786: The Conspiracy and the Hoax) by Paolo Mazzarello Bollati Boringhieri: 2004. 327 pp. €24. In Italian. http://www.bollatiboringhieri.it/ Nicola Nosengo The second half of the eighteenth century was a time of spectacular advances in the life sciences. Fundamental problems such as the generation of life were addressed for the first time using modern experimental tools. But these issues were the source of great controversy, and also great rivalries among Lazzaro Spallanzani poured scorn on rivals whose experiments failed to meet his own high standards. biologists — or philosophers, as they still preferred to call themselves. was a genuine scientific mission.Spallanzani known. Using a pen name, he wrote a At a time when many scientists were still left Pavia equipped with scientific instru- pamphlet, full of scorn and cruel irony, convinced that life can be generated sponta- ments, such as barometers, thermometers, condemning Scopoli’s ability as a scientist. neously from decomposition, the Italian lenses and a microscope. He spent most of Scopoli,he wrote,wanted to study nature Lazzaro Spallanzani was the first to demon- his time taking measurements and collecting inside “dead museums”, only hoping to be stratethe necessity of sperm for reproduction. -

FOURTH UPDATE to a CHECKLIST of the LEPIDOPTERA of the BRITISH ISLES , 2013 1 David J

Ent Rec 133(1).qxp_Layout 1 13/01/2021 16:46 Page 1 Entomologist’s Rec. J. Var. 133 (2021) 1 FOURTH UPDATE TO A CHECKLIST OF THE LEPIDOPTERA OF THE BRITISH ISLES , 2013 1 DAvID J. L. A GASSIz , 2 S. D. B EAvAN & 1 R. J. H ECkFoRD 1 Department of Life Sciences, Division of Insects, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD 2 The Hayes, Zeal Monachorum, Devon EX17 6DF Abstract This update incorporates information published since 30 November 2019 and before 1 January 2021 into A Checklist of the Lepidoptera of the British Isles, 2013. Introduction The Checklist of the Lepidoptera of the British Isles has previously been amended (Agassiz, Beavan & Heckford 2016a, 2016b, 2019 and 2020). This update details 4 species new to the main list and 3 to Appendix A. Numerous taxonomic changes are incorporated and country distributions are updated. CENSUS The number of species now recorded from the British Isles stands at 2,558 of which 58 are thought to be extinct and in addition there are 191 adventive species. ADDITIONAL SPECIES in main list Also make appropriate changes in the index 15.0715 Phyllonorycter medicaginella (Gerasimov, 1930) E S W I C 62.0382 Acrobasis fallouella (Ragonot, 1871) E S W I C 70.1698 Eupithecia breviculata (Donzel, 1837) Rusty-shouldered Pug E S W I C 72.089 Grammodes bifasciata (Petagna, 1786) Parallel Lines E S W I C The authorship and date of publication of Grammodes bifasciata were given by Brownsell & Sale (2020) as Petagan, 1787 but corrected to Petagna, 1786 by Plant (2020). -

Schutz Des Naturhaushaltes Vor Den Auswirkungen Der Anwendung Von Pflanzenschutzmitteln Aus Der Luft in Wäldern Und Im Weinbau

TEXTE 21/2017 Umweltforschungsplan des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit Forschungskennzahl 3714 67 406 0 UBA-FB 002461 Schutz des Naturhaushaltes vor den Auswirkungen der Anwendung von Pflanzenschutzmitteln aus der Luft in Wäldern und im Weinbau von Dr. Ingo Brunk, Thomas Sobczyk, Dr. Jörg Lorenz Technische Universität Dresden, Fakultät für Umweltwissenschaften, Institut für Forstbotanik und Forstzoologie, Tharandt Im Auftrag des Umweltbundesamtes Impressum Herausgeber: Umweltbundesamt Wörlitzer Platz 1 06844 Dessau-Roßlau Tel: +49 340-2103-0 Fax: +49 340-2103-2285 [email protected] Internet: www.umweltbundesamt.de /umweltbundesamt.de /umweltbundesamt Durchführung der Studie: Technische Universität Dresden, Fakultät für Umweltwissenschaften, Institut für Forstbotanik und Forstzoologie, Professur für Forstzoologie, Prof. Dr. Mechthild Roth Pienner Straße 7 (Cotta-Bau), 01737 Tharandt Abschlussdatum: Januar 2017 Redaktion: Fachgebiet IV 1.3 Pflanzenschutz Dr. Mareike Güth, Dr. Daniela Felsmann Publikationen als pdf: http://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen ISSN 1862-4359 Dessau-Roßlau, März 2017 Das diesem Bericht zu Grunde liegende Vorhaben wurde mit Mitteln des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit unter der Forschungskennzahl 3714 67 406 0 gefördert. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröffentlichung liegt bei den Autorinnen und Autoren. UBA Texte Entwicklung geeigneter Risikominimierungsansätze für die Luftausbringung von PSM Kurzbeschreibung Die Bekämpfung -

Contribution to the Knowledge of the Fauna of Bombyces, Sphinges And

driemaandelijks tijdschrift van de VLAAMSE VERENIGING VOOR ENTOMOLOGIE Afgiftekantoor 2170 Merksem 1 ISSN 0771-5277 Periode: oktober – november – december 2002 Erkenningsnr. P209674 Redactie: Dr. J–P. Borie (Compiègne, France), Dr. L. De Bruyn (Antwerpen), T. C. Garrevoet (Antwerpen), B. Goater (Chandlers Ford, England), Dr. K. Maes (Gent), Dr. K. Martens (Brussel), H. van Oorschot (Amsterdam), D. van der Poorten (Antwerpen), W. O. De Prins (Antwerpen). Redactie-adres: W. O. De Prins, Nieuwe Donk 50, B-2100 Antwerpen (Belgium). e-mail: [email protected]. Jaargang 30, nummer 4 1 december 2002 Contribution to the knowledge of the fauna of Bombyces, Sphinges and Noctuidae of the Southern Ural Mountains, with description of a new Dichagyris (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae, Endromidae, Saturniidae, Sphingidae, Notodontidae, Noctuidae, Pantheidae, Lymantriidae, Nolidae, Arctiidae) Kari Nupponen & Michael Fibiger [In co-operation with Vladimir Olschwang, Timo Nupponen, Jari Junnilainen, Matti Ahola and Jari- Pekka Kaitila] Abstract. The list, comprising 624 species in the families Lasiocampidae, Endromidae, Saturniidae, Sphingidae, Notodontidae, Noctuidae, Pantheidae, Lymantriidae, Nolidae and Arctiidae from the Southern Ural Mountains is presented. The material was collected during 1996–2001 in 10 different expeditions. Dichagyris lux Fibiger & K. Nupponen sp. n. is described. 17 species are reported for the first time from Europe: Clostera albosigma (Fitch, 1855), Xylomoia retinax Mikkola, 1998, Ecbolemia misella (Püngeler, 1907), Pseudohadena stenoptera Boursin, 1970, Hadula nupponenorum Hacker & Fibiger, 2002, Saragossa uralica Hacker & Fibiger, 2002, Conisania arida (Lederer, 1855), Polia malchani (Draudt, 1934), Polia vespertilio (Draudt, 1934), Polia altaica (Lederer, 1853), Mythimna opaca (Staudinger, 1899), Chersotis stridula (Hampson, 1903), Xestia wockei (Möschler, 1862), Euxoa dsheiron Brandt, 1938, Agrotis murinoides Poole, 1989, Agrotis sp. -

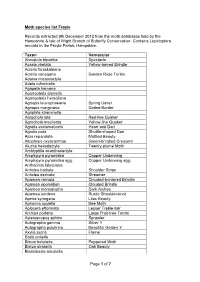

Page 1 of 7 Moth Species List Froyle Records

Moth species list Froyle Records extracted 9th December 2012 from the moth databases held by the Hampshire & Isle of Wight Branch of Butterfly Conservation. Contains Lepidoptera records in the Froyle Parish, Hampshire. Taxon Vernacular Abrostola tripartita Spectacle Acasis viretata Yellow-barred Brindle Acleris forsskaleana Acleris variegana Garden Rose Tortrix Adaina microdactyla Adela rufimitrella Agapeta hamana Agonopterix arenella Agonopterix heracliana Agriopis leucophaearia Spring Usher Agriopis marginaria Dotted Border Agriphila straminella Agrochola lota Red-line Quaker Agrochola macilenta Yellow-line Quaker Agrotis exclamationis Heart and Dart Agrotis puta Shuttle-shaped Dart Alcis repandata Mottled Beauty Allophyes oxyacanthae Green-brindled Crescent Alucita hexadactyla Twenty-plume Moth Amblyptilia acanthadactyla Amphipyra pyramidea Copper Underwing Amphipyra pyramidea agg. Copper Underwing agg. Anthophila fabriciana Anticlea badiata Shoulder Stripe Anticlea derivata Streamer Apamea crenata Clouded-bordered Brindle Apamea epomidion Clouded Brindle Apamea monoglypha Dark Arches Apamea sordens Rustic Shoulder-knot Apeira syringaria Lilac Beauty Aphomia sociella Bee Moth Aplocera efformata Lesser Treble-bar Archips podana Large Fruit-tree Tortrix Asteroscopus sphinx Sprawler Autographa gamma Silver Y Autographa pulchrina Beautiful Golden Y Axylia putris Flame Batia unitella Biston betularia Peppered Moth Biston strataria Oak Beauty Blastobasis adustella Page 1 of 7 Blastobasis lacticolella Cabera exanthemata Common Wave Cabera