Scorched: Extreme Heat and Real Estate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missionary Perspectives and Experiences of 19Th and Early 20Th Century Droughts

1 2 “Everything is scorched by the burning sun”: Missionary perspectives and 3 experiences of 19th and early 20th century droughts in semi-arid central 4 Namibia 5 6 Stefan Grab1, Tizian Zumthurm,2,3 7 8 1 School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the 9 Witwatersrand, South Africa 10 2 Institute of the History of Medicine, University of Bern, Switzerland 11 3 Centre for African Studies, University of Basel, Switzerland 12 13 Correspondence to: Stefan Grab ([email protected]) 14 15 Abstract. Limited research has focussed on historical droughts during the pre-instrumental 16 weather-recording period in semi-arid to arid human-inhabited environments. Here we describe 17 the unique nature of droughts over semi-arid central Namibia (southern Africa) between 1850 18 and 1920. More particularly, our intention is to establish temporal shifts of influence and 19 impact that historical droughts had on society and the environment during this period. This is 20 achieved through scrutinizing documentary records sourced from a variety of archives and 21 libraries. The primary source of information comes from missionary diaries, letters and reports. 22 These missionaries were based at a variety of stations across the central Namibian region and 23 thus collectively provide insight to sub-regional (or site specific) differences in hydro- 24 meteorological conditions, and drought impacts and responses. Earliest instrumental rainfall 25 records (1891-1913) from several missionary stations or settlements are used to quantify hydro- 26 meteorological conditions and compare with documentary sources. The work demonstrates 27 strong-sub-regional contrasts in drought conditions during some given drought events and the 28 dire implications of failed rain seasons, the consequences of which lasted many months to 29 several years. -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

How Climate Change Scorched the Nation in 2012

HOW CLIMATE CHANGE SCORCHED THE NATION IN 2012 NatioNal Wildlife federatioN i. Intro- ductioN Photo: Flickr/woodleywonderworks is climate change ruining our summers? It is certainly altering them in dramatic ways, and rarely for the better. The summer of 2012 has been full of extreme weather events connected to climate change. Heat records have been broken across the country, drought conditions forced the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to make the largest disaster declaration in U.S. history, and wildfires have raged throughout the West. New research by world-renowned climate scientist James Hansen con- firms that the increasingly common extreme weather events across the country, like record heat waves and drought, are linked to climate change.1 This report examines those climate change impacts whose harm is acutely felt in the summer. Heat waves; warming rivers, lakes, and streams; floods; drought; wildfires; and insect and pest infestations are problems we are dealing with this summer and what we are likely to face in future summers. As of August 23rd, 7 MILLION 2/3 of the country has experienced drought this acres of wildlife habitat and communities summer, much of it labeled “severe” 4 have burned in wildfires2 40 20 60 More than July’s average0 continental U.S. temperature 80 -20 113 MILLION 77.6°F100 people in the U.S. were in areas under 3.3°F above-40 the 20th-century average. 3 5 extreme heat advisories as of June 29 This was the-60 warmest month120 on record 0F NatioNal Wildlife federatioN Unfortunately, hot summers like this will occur much more frequently in years ahead. -

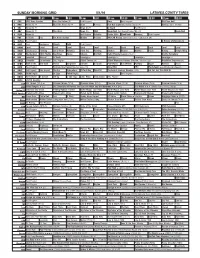

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Effects of a Prescribed Fire on Oak Woodland Stand Structure1

Effects of a Prescribed Fire on Oak Woodland Stand Structure1 Danny L. Fry2 Abstract Fire damage and tree characteristics of mixed deciduous oak woodlands were recorded after a prescription burn in the summer of 1999 on Mt. Hamilton Range, Santa Clara County, California. Trees were tagged and monitored to determine the effects of fire intensity on damage, recovery and survivorship. Fire-caused mortality was low; 2-year post-burn survey indicates that only three oaks have died from the low intensity ground fire. Using ANOVA, there was an overall significant difference for percent tree crown scorched and bole char height between plots, but not between tree-size classes. Using logistic regression, tree diameter and aspect predicted crown resprouting. Crown damage was also a significant predictor of resprouting with the likelihood increasing with percent scorched. Both valley and blue oaks produced crown resprouts on trees with 100 percent of their crown scorched. Although overall tree damage was low, crown resprouts developed on 80 percent of the trees and were found as shortly as two weeks after the fire. Stand structural characteristics have not been altered substantially by the event. Long term monitoring of fire effects will provide information on what changes fire causes to stand structure, its possible usefulness as a management tool, and how it should be applied to the landscape to achieve management objectives. Introduction Numerous studies have focused on the effects of human land use practices on oak woodland stand structure and regeneration. Studies examining stand structure in oak woodlands have shown either persistence or strong recruitment following fire (McClaran and Bartolome 1989, Mensing 1992). -

The Forest Resiliency Burning Pilot Project

R E S O U C The Forest Resiliency Burning Pilot Project December 2018 N A T U R L The Forest Resiliency Burning Pilot Project Report to the Legislature December 2018 Prepared by Washington State Department of Natural Resources and Washington Prescribed Fire Council Cover photo by © John Marshall. ii Executive Summary More than 100 years of fire suppression and land management practices have severely degraded Eastern Washington’s fire-adapted dry forests. Without the regular, low-intensity fires that created their open stand structure and resiliency, tree density has increased and brush and dead fuels have accumulated in the understory. The impact of these changes in combination with longer fire seasons have contributed to back-to-back record-breaking wildfire years, millions spent in firefighting resources and recovery, danger to our communities, and millions of acres of severely burned forest. Forest resiliency burning, also called prescribed fire or controlled burning, returns fire as an essential ecological process to these forests and is an effective tool for reducing fuels and associated risk of severe fires. Forest experts have identified 2.7 million acres of Central and Eastern Washington forests in need of restoration (Haugo et al. 2015). The agency’s 20-year Forest Health Strategic Plan addresses the need to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration treatments, which includes the use of prescribed fire. Successful implementation of prescribed fire in dry forest ecosystems faces a number of challenges, primarily unfavorable weather conditions, smoke management regulations, and some public opposition. Recognizing these challenges, the urgent need for large-scale forest restoration, and the usefulness and benefits of prescribed fire, the Legislature passed Engrossed Substitute House Bill (ESHB) 2928. -

6INTER-30:Maquetación 1.Qxd

6 CULTURALES JULIO 2015 > jueves 30 ENVIADA POR LA TV CUBANA CUBAVISIÓN Vida y milagros del DDT 8:00 Animados 8:30 Mr. Magoo 9:00 ¿Sabes qué? Madeleine Sautié Rodríguez medio natural, que es la sociedad, y 9:15 Todo mezclado 9:45 Aquí estoy yo (cap. 4) a la de determinar su función útil, 10:15 Juega y aprende 10:30 Lluvia de alegría Como parte del ciclo que dedica (Enrique Bergson, premio Nobel del 10:45 Chiquilladas 11:00 Ventana juvenil 11:15 La el espacio Miércoles de Sonrisas a la año 1927); y citando a H. Zumbado ronca de oro (cap. 10) 12:00 Al mediodía 1:00 No - publicación humorística DDT, su recordó que “el humor es un arma, ticiero del mediodía 2:00 Cuentos que sí son cuen- anfitriona, Laidi Fernández de Juan, porque critica y desnuda al mismo tos: Jack el caza gigantes. EE.UU./fantástico 4:00 Noticiero Ansoc 4:15 Muñe en TV 4:45 Bar quito de invitó en la más reciente edición, en tiempo, y lo hace con una sonrisa en papel 5:12 Para saber mañana 5:15 Lente joven el capitalino Centro Cultural Dulce los labios”, mientras que para Ale - 5:45 Los hombres también lloran (cap. 19) 6:30 María Loy naz, a los escritores Jorge jandro García, Virulo, “Los humo- Noticiero cultural 7:00 Mesa Redonda 8:00 NTV Tomás Tei jeiro y Félix Mondéjar, quie- ristas somos personas que decimos 8:33 Documental: Yeyé, dedicado a Haydée San - nes formaron parte por varios años las cosas en serio y los demás se tamaría 9:36 Cuando el amor no alcanza (cap. -

The Report: Killer Heat in the United States

Killer Heat in the United States Climate Choices and the Future of Dangerously Hot Days Killer Heat in the United States Climate Choices and the Future of Dangerously Hot Days Kristina Dahl Erika Spanger-Siegfried Rachel Licker Astrid Caldas John Abatzoglou Nicholas Mailloux Rachel Cleetus Shana Udvardy Juan Declet-Barreto Pamela Worth July 2019 © 2019 Union of Concerned Scientists The Union of Concerned Scientists puts rigorous, independent All Rights Reserved science to work to solve our planet’s most pressing problems. Joining with people across the country, we combine technical analysis and effective advocacy to create innovative, practical Authors solutions for a healthy, safe, and sustainable future. Kristina Dahl is a senior climate scientist in the Climate and Energy Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. More information about UCS is available on the UCS website: www.ucsusa.org Erika Spanger-Siegfried is the lead climate analyst in the program. This report is available online (in PDF format) at www.ucsusa.org /killer-heat. Rachel Licker is a senior climate scientist in the program. Cover photo: AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin Astrid Caldas is a senior climate scientist in the program. In Phoenix on July 5, 2018, temperatures surpassed 112°F. Days with extreme heat have become more frequent in the United States John Abatzoglou is an associate professor in the Department and are on the rise. of Geography at the University of Idaho. Printed on recycled paper. Nicholas Mailloux is a former climate research and engagement specialist in the Climate and Energy Program at UCS. Rachel Cleetus is the lead economist and policy director in the program. -

Heat Waves in Southern California: Are They Becoming More Frequent and Longer Lasting?

Heat Waves in Southern California: Are They Becoming More Frequent and Longer Lasting? A!"# T$%!$&#$' University of California, Berkeley S()*) L$D+,-. California State University, Los Angeles J+/- W#00#/ $'1 W#00#$% C. P$(&)!( Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA ABSTRACT Los Angeles is experiencing more heat waves and also more extreme heat days. 2ese numbers have increased by over 3 heat waves per century and nearly 23 days per century occurrences, respectively. Both have more than tripled over the past 100 years as a consequence of the steady warming of Los Angeles. Our research explores the daily maximum and minimum temper- atures from 1906 to 2006 recorded by the Department of Water and Power (DWP) downtown station and Pierce College, a suburban valley location. 2e average annual maximum temperature in Los Angeles has warmed by 5.0°F (2.8°C), while the average annual minimum temperature has warmed by 4.2°F (2.3°C). 2e greatest rate of change was during the summer months for both maximum and minimum temperature, with late fall and early winter having the least rates of change. 2ere was also an increase in heat wave duration. Heat waves lasting longer than six days occurred regularly a3er the 1970s but were nonexistent from the start of 1906 until 1956, when the 4rst six-day heat wave was recorded. While heat days have increased dramatically in the past century, cold days, where minimum temperature is below 45°F (7.2°C), show a slight decreasing trend. Recent deadly heat waves in the western United States have generated increasing electricity demands. -

Magnitude and Frequency of Heat and Cold Waves in Recent Table 1

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 3, 7379–7409, 2015 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/3/7379/2015/ doi:10.5194/nhessd-3-7379-2015 NHESSD © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 3, 7379–7409, 2015 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Natural Hazards and Earth Magnitude and System Sciences (NHESS). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in NHESS if available. frequency of heat and cold waves in recent Magnitude and frequency of heat and cold decades: the case of South America waves in recent decades: the case of G. Ceccherini et al. South America G. Ceccherini1, S. Russo1, I. Ameztoy1, C. P. Romero2, and C. Carmona-Moreno1 Title Page Abstract Introduction 1DG Joint Research Centre, European Commission, Ispra 21027, Italy 2 Facultad de Ingeniería Ambiental, Universidad Santo Tomás, Bogota 5878797, Colombia Conclusions References Received: 12 November 2015 – Accepted: 23 November 2015 – Published: Tables Figures 10 December 2015 Correspondence to: G. Ceccherini ([email protected]) J I Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. J I Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 7379 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract NHESSD In recent decades there has been an increase in magnitude and occurrence of heat waves and a decrease of cold waves which are possibly related to the anthropogenic 3, 7379–7409, 2015 influence (Solomon et al., 2007). This study describes the extreme temperature regime 5 of heat waves and cold waves across South America over recent years (1980–2014). -

Officina Delle Arti’ Concerto-Evento Dei Cluster Il Più Importante Gruppo Di Elettronica D'avanguardia Nato Negli Anni '70

COMUNE DI REGGIO EMILIA Ufficio Stampa ________________________________________________________________________________ Martedì 12 febbraio 2008 Sabato 16 febbraio a ‘Officina delle Arti’ concerto-evento dei Cluster il più importante gruppo di elettronica d'avanguardia nato negli anni '70 Oggi ancora attivo nella sua formazione storica, il duo formato dai tastieristi Dieter Moebius e Hans Joachim Roedelius. Sabato 16 febbraio, dopo oltre 20 anni di assenza dall'Italia, i Cluster arrivano nel salone centrale dell'Officina delle Arti (via Brigata Reggio 29) a Reggio Emilia, con un concerto che avrà inizio a partire dalle ore 21. In occasione della performance verrà effettuata la presentazione della ristampa riveduta e corretta di Cosmic Dreams at Play, la bibbia della musica creativa tedesca scritta dal saggista norvegese Dag Erik Asbjornsen. La riedizione del testo è il primo libro pubblicato da 'Strange Vertigo', nuova iniziativa editoriale reggiana specializzata nel recupero di testi ormai irreperibili nel campo della saggistica musicale e cinematografica. L’evento è promosso da Officina delle arti, il centro per le arti contemporanee voluto dal Comune di Reggio Emilia-assessorato Cultura. Sponsor tecnico dell’evento è Pro Music. Ingresso gratuito e limitato ai posti disponibili. INFO: tel. 0522 456249 Cluster è il più importante gruppo di elettronica d'avanguardia nato negli anni '70, oggi ancora attivo nella sua formazione storica, il duo formato dai tastieristi Dieter Moebius e Hans Joachim Roedelius. La formazione viene fondata da questi assieme a Conrad Schnitzler nel 1970, con il nome di ‘Kluster’, sulla scia di esperienze artistiche, anche poetiche e figurative, condivise nel collettivo Zodiak nella turbolenta Berlino di fine anni '60. -

17-06-27 Full Stock List Drone

DRONE RECORDS FULL STOCK LIST - JUNE 2017 (FALLEN) BLACK DEER Requiem (CD-EP, 2008, Latitudes GMT 0:15, €10.5) *AR (RICHARD SKELTON & AUTUMN RICHARDSON) Wolf Notes (LP, 2011, Type Records TYPE093V, €16.5) 1000SCHOEN Yoshiwara (do-CD, 2011, Nitkie label patch seven, €17) Amish Glamour (do-CD, 2012, Nitkie Records Patch ten, €17) 1000SCHOEN / AB INTRA Untitled (do-CD, 2014, Zoharum ZOHAR 070-2, €15.5) 15 DEGREES BELOW ZERO Under a Morphine Sky (CD, 2007, Force of Nature FON07, €8) Between Checks and Artillery. Between Work and Image (10inch, 2007, Angle Records A.R.10.03, €10) Morphine Dawn (maxi-CD, 2004, Crunch Pod CRUNCH 32, €7) 21 GRAMMS Water-Membrane (CD, 2012, Greytone grey009, €12) 23 SKIDOO Seven Songs (do-LP, 2012, LTM Publishing LTMLP 2528, €29.5) 2:13 PM Anus Dei (CD, 2012, 213Records 213cd07, €10) 2KILOS & MORE 9,21 (mCD-R, 2006, Taalem alm 37, €5) 8floors lower (CD, 2007, Jeans Records 04, €13) 3/4HADBEENELIMINATED Theology (CD, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 148, €19.5) Oblivion (CD, 2010, Die Schachtel DSZeit11, €14) Speak to me (LP, 2016, Black Truffle BT023, €17.5) 300 BASSES Sei Ritornelli (CD, 2012, Potlatch P212, €15) 400 LONELY THINGS same (LP, 2003, Bronsonunlimited BRO 000 LP, €12) 5IVE Hesperus (CD, 2008, Tortuga TR-037, €16) 5UU'S Crisis in Clay (CD, 1997, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu2, €14) Hunger's Teeth (CD, 1994, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu1, €14) 7JK (SIEBEN & JOB KARMA) Anthems Flesh (CD, 2012, Redroom Records REDROOM 010 CD , €13) 87 CENTRAL Formation (CD, 2003, Staalplaat STCD 187, €8) @C 0° - 100° (CD, 2010, Monochrome