Herb Brooks the Inside Story of a Hockey Mastermind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 4- 2019-20 WCHA Postseason History.Indd

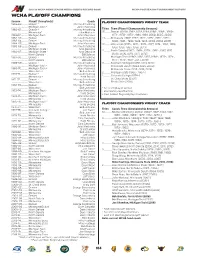

2019-20 WCHA MEN'S LEAGUE MEDIA GUIDE & RECORD BOOK WCHA POSTSEASON TOURNAMENT HISTORY WCHA PLAYOFF CHAMPIONS Season Playoff Champion(s) Coach PLAYOFF CHAMPIONSHIPS WON BY TEAM 1959-60 ...........Denver * Murray Armstrong .............................Michigan Tech * John MacInnes 1960-61 ............Denver * Murray Armstrong Titles Team (Playoff Championship Seasons) .............................Minnesota* John Mariucci 15 ..........Denver (1960*, 1961*, 1963, 1964, 1966•, 1968•, 1969+, 1961-62 ............Michigan Tech John MacInnes 1971+, 1972•, 1973•, 1986, 1999, 2002, 2005, 2008) 1962-63............Denver Murray Armstrong 14 ..........Minnesota (1961*, 1971+, 1974•, 1975•, 1976•, 1979•, 1963-64 ...........Denver Murray Armstrong 1980•, 1981•, 1993, 1994, 1996, 2003, 2004, 2007) 1964-65 ...........Michigan Tech John MacInnes 12 ..........Wisconsin (1970+, 1972•, 1973•, 1977, 1978•, 1982, 1983, 1965-66 ...........Denver • Murray Armstrong 1988, 1990, 1995, 1998, 2013) .............................Michigan State • Amo Bessone 11 ...........North Dakota (1967•, 1968•, 1979•, 1980•, 1987, 1997, 1966-67 ............Michigan State • Amo Bessone .............................North Dakota • Bill Selman 2000, 2006, 2010, 2011, 2012) 1967-68 ............Denver • Murray Armstrong Michigan Tech (1960*, 1962, 1965, 1969+, 1970+, 1974•, .............................North Dakota • Bill Selman 1975•, 1976•, 1981•, 2017, 2018) 1968-69 ...........Denver + Murray Armstrong 3 ............Northern Michigan (1989, 1991, 1992) .............................Michigan -

1977-78 Topps Hockey Card Set Checklist

1977-78 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Marcel Dionne Goals Leaders 2 Tim Young Assists Leaders 3 Steve Shutt Scoring Leaders 4 Bob Gassoff Penalty Minute Leaders 5 Tom Williams Power Play Goals Leaders 6 Glenn "Chico" Resch Goals Against Average Leaders 7 Peter McNab Game-Winning Goal Leaders 8 Dunc Wilson Shutout Leaders 9 Brian Spencer 10 Denis Potvin Second Team All-Star 11 Nick Fotiu 12 Bob Murray 13 Pete LoPresti 14 J.-Bob Kelly 15 Rick MacLeish 16 Terry Harper 17 Willi Plett RC 18 Peter McNab 19 Wayne Thomas 20 Pierre Bouchard 21 Dennis Maruk 22 Mike Murphy 23 Cesare Maniago 24 Paul Gardner RC 25 Rod Gilbert 26 Orest Kindrachuk 27 Bill Hajt 28 John Davidson 29 Jean-Paul Parise 30 Larry Robinson First Team All-Star 31 Yvon Labre 32 Walt McKechnie 33 Rick Kehoe 34 Randy Holt RC 35 Garry Unger 36 Lou Nanne 37 Dan Bouchard 38 Darryl Sittler 39 Bob Murdoch 40 Jean Ratelle 41 Dave Maloney 42 Danny Gare Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jim Watson 44 Tom Williams 45 Serge Savard 46 Derek Sanderson 47 John Marks 48 Al Cameron RC 49 Dean Talafous 50 Glenn "Chico" Resch 51 Ron Schock 52 Gary Croteau 53 Gerry Meehan 54 Ed Staniowski 55 Phil Esposito 56 Dennis Ververgaert 57 Rick Wilson 58 Jim Lorentz 59 Bobby Schmautz 60 Guy Lapointe Second Team All-Star 61 Ivan Boldirev 62 Bob Nystrom 63 Rick Hampton 64 Jack Valiquette 65 Bernie Parent 66 Dave Burrows 67 Robert "Butch" Goring 68 Checklist 69 Murray Wilson 70 Ed Giacomin 71 Atlanta Flames Team Card 72 Boston Bruins Team Card 73 Buffalo Sabres Team Card 74 Chicago Blackhawks Team Card 75 Cleveland Barons Team Card 76 Colorado Rockies Team Card 77 Detroit Red Wings Team Card 78 Los Angeles Kings Team Card 79 Minnesota North Stars Team Card 80 Montreal Canadiens Team Card 81 New York Islanders Team Card 82 New York Rangers Team Card 83 Philadelphia Flyers Team Card 84 Pittsburgh Penguins Team Card 85 St. -

AMERICAN HOCKEY COACHES ASSOCIATION Executive Director: Joe Bertagna — 7 Concord Street — Gloucester, MA 01930 — (781) 245-4177

AMERICAN HOCKEY COACHES ASSOCIATION Executive Director: Joe Bertagna — 7 Concord Street — Gloucester, MA 01930 — (781) 245-4177 For immediate release: Wednesday, April 10, 2013 Norm Bazin of UMass Lowell Named flexxCOACH/AHCA Men’s Division I Coach of the Year Will Receive Spencer Penrose Award at AHCA Convention on May 4 in Naples, FL For his efforts in leading UMass Lowell to its first NCAA Division I Men’s Ice Hockey “Frozen Four” appearance in school history, Norm Bazin has been chosen winner of the 2013 Spencer Penrose Award as Division I Men’s Ice Hockey flexxCOACH/AHCA Coach of the Year. He will receive his award on Saturday evening, May 4, during the American Hockey Coaches Association annual convention in Naples, FL. Entering Thursday afternoon’s semifinal contest vs. Yale, Bazin’s River Hawks have compiled an overall record of 28-10-2, capturing both the Hockey East regular season and tournament titles along the way. Lowell advanced to the Frozen Four by defeating Wisconsin (6-1) and New Hampshire (2-0) to win the NCAA Northeast Regional in Manchester, NH. The River Hawks enter the Frozen Four in Pittsburgh’s CONSOL Energy Center having won 14 of their last 15 games and seven in a row. On December 1, the UMass Lowell record stood at 4-7-1. Since that time, they have gone 24-3-1. Bazin has been chosen as the Hockey East Coach of the Year in both of his seasons at Lowell. This follows two years as the NESCAC Coach of the Year while he coached at Hamilton College. -

Ross Bernstein Motivational Speaker & Best-Selling Sports Author

SUSAN GUZZETTA PROFESSIONAL SPEAKERS FOR ALL OCCASIONS ROSS BERNSTEIN MOTIVATIONAL SPEAKER & BEST-SELLING SPORTS AUTHOR SPEAKER The best-selling author of nearly 50 sports books, Ross Bernstein is an award-winning peak performance business speaker who’s keynoted conferences on four continents for audiences as small as 10 and as large as 10,000. Ross and his books have been featured on thousands of television and radio programs over the years including CNN, ESPN, Bloomberg, Fox News, and “CBS This Morning,” as well as in the Wall Street Journal, New York Times and USA Today. He’s spent the better part of the past 20 years studying the DNA of championship teams and his program, “The Champion’s Code: Building Relationships Through Life Lessons of Integrity and Accountability from the Sports World to the Business World,” not only illustrates what it takes to become the best of the best, it also explores the fine line between cheating and gamesmanship in sports as it relates to values and integrity in the workplace. As a working member of the media in his home state of Minnesota, Ross has a unique behind the scenes access to all of the local sports franchises in the area, including the Vikings, Twins, Timberwolves, Wild and Gophers. As such, he spends lots of his time in dugouts, club houses, locker rooms, and press boxes — and it’s here where Ross has met and interviewed thousands of professional athletes over the years. Ross and his wife Sara have a 12 year old daughter and presently reside in Apple Valley, MN. -

St. Cloud State Huskies 2014-15 Schedule Quick Facts Date Opponent Time (CT) Sat., Oct

St. Cloud State HuSkieS 2014-15 Schedule Quick Facts Date Opponent Time (CT) Sat., Oct. 4 Trinity Western (Exh.) 7:00 p.m. Location (Pop.): ..................... St. Cloud, Minn. (66,297) Fri., Oct. 10 Colgate 7:37 p.m. Founded: ............................................................... 1869 Sat., Oct. 11 Colgate 7:07 p.m. Enrollment: ......................................................... 16,245 Fri., Oct. 24 at Union 6:00 p.m. Sat., Oct. 25 at Union 6:00 p.m. Nickname:..........................................................Huskies Fri., Oct. 31 Minnesota 7:37 p.m. Colors: ............................................. Cardinal and Black Sat., Nov. 1 at Minnesota 4:00 p.m. President: ....................................... Dr. Earl H. Potter III Fri., Nov. 7 Minnesota Duluth* 7:37 p.m. Director of Athletics:............................. Heather Weems Sat., Nov. 8 Minnesota Duluth* 7:07 p.m. Hockey Admin.:.................................... Heather Weems Fri., Nov. 14 at Western Michigan* 6:00 p.m. Faculty Athletic Rep.: ..............................Dr. Bill Hudson Sat., Nov. 15 at Western Michigan* 6:00 p.m. Athletic Dept. Phone #: ..........................(320) 308-3102 Fri., Nov. 21 North Dakota* 7:37 p.m. Sat., Nov. 22 North Dakota* 7:07 p.m. SEASON IN REVIEW Fri., Nov. 28 at Bemidji State 7:37 p.m. 2013-14 Overall Record: ................................... 22-11-5 Sat., Nov. 29 at Bemidji State 7:07 p.m. 2013-14 NCHC Record/Finish: ...................15-6-3-0/1st Fri., Dec. 12 at Omaha* 7:37 p.m. 2014 NCHC Tournament Record: ............................. 0-2 Sat., Dec. 13 at Omaha* 7:07 p.m. 2014 NCHC Tournament Finish: ................Quarterfinals Fri., Jan. 2 Quinnipiac 7:37 p.m. 2014 NCAA Tournament Finish: ............. Regional Final Sat., Jan. -

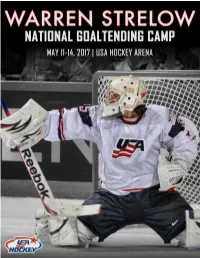

Who Is Warren Strelow?

WHO IS WARREN STRELOW? Warren Strelow served as the goaltending coach for the 1980 U.S. Olympic team in Lake Placid, NY. In 1983, Strelow was hired by the Washington Capitals and became the first full time goal- tending coach in the NHL. He also coached for the New Jersey Devils and the San Jose Sharks before passing away in 2007. WHAT IS THE WARREN STRELOW NATIONAL GOALTENDING CAMP? This is a select camp made up of the top goaltenders in each age group eligible for international play. The elite four-day camp will cover both physical and mental aspects of goaltending, helping each player master the fundamentals of the position while developing a personal identity that translates to in-game success. The camp consists of on-ice drill training and off-ice breakout classroom sessions that aid in learning the position. There will also be keynote speakers to offer their expertise in various forms of the games. 2017 CAMP SCHEDULE DATE TIME ACTIVITY Wednesday, May 10 All day Staff arrivals and meetings Thursday, May 11 Morning Staff meetings, player arrivals 2:30 - 5 p.m. Ice sessions Friday, May 12 9 a.m. - 12 p.m. On-ice/off-ice sessions 12:30 p.m. Break-Out Sessions 2:30 - 5 p.m. On-ice/off-ice sessions Saturday, May 13 9 a.m. - 12 p.m. On-ice/off-ice sessions 12:30 p.m. Break-Out Sessions 2:30 - 5 p.m. On-ice/off-ice sessions Sunday, May 14 8 - 10:30 a.m. On-ice sessions 12 p.m. -

2019 CAROLINA HURRICANES DRAFT GUIDE Rogers Arena • Vancouver, B.C

2019 CAROLINA HURRICANES DRAFT GUIDE Rogers Arena • Vancouver, B.C. Round 1: Friday, June 21 – 8 P.M. ET (NBCSN) Hurricanes pick: 28th overall Rounds 2-7: Saturday, June 22 – 1 P.M. ET (NHL Network) Hurricanes picks: Round 2: 36th overall (from BUF), 37th overall (from NYR) and 59th overall; Round 3: 90th overall; Round 4: 121st overall; Round 5: 152nd overall; Round 6: 181st overall (from CGY) and 183rd overall; Round 7: 216th overall (from BOS via NYR) The Carolina Hurricanes hold ten picks in the 2019 NHL Draft, including four in the first two rounds. The first round of the NHL Draft begins on Friday, June 21 at Rogers Arena in Vancouver and will be televised on NBCSN at 8 p.m. ET. Rounds 2-7 will take place on Saturday, June 22 at 1 p.m. ET and will be televised on NHL Network. The Hurricanes made six selections in the 2018 NHL Draft in Dallas, including second-overall pick Andrei Svechnikov. HURRICANES ALL-TIME FIRST HURRICANES DRAFT NOTES ROUND SELECTIONS History of the 28th Pick – Carolina’s first selection in the 2019 NHL Draft will be 28th overall in the first round. Hurricanes captain Justin Williams was taken 28th overall by Year Overall Player Philadelphia in the 2000 NHL Draft, and his 786 career points (312g, 474a) are the most 2018 2 Andrei Svechnikov, RW all-time by a player selected 28th. Other notable active NHL players drafted 28th overall 2017 12 Martin Necas, C include Cory Perry, Nick Foligno, Matt Niskanen, Charlie Coyle, and Brady Skjei. -

Cold War and the Olympics: an Athlete's Perspective Mike Vecchione Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2017 Cold War and the Olympics: An Athlete's Perspective Mike Vecchione Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Vecchione, Mike, "Cold War and the Olympics: An Athlete's Perspective" (2017). Honors Theses. 97. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/97 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Union College Cold War and the Olympics: An Athlete’s Perspective Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Honors Department of History Mike Vecchione History Thesis Professor Aslakson 3/16/17 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction-3 The Olympic Boycotts-3 ChapterHistoriography-6 Description- 17 Chapter 2: United States Cheated of Gold- 19 The Alternate Endings-19 The Appeal- 24 Background of William Jones-28 Player’s Reactions- 35 Chapter 3: Miracle On Ice- 40 Herb Brooks’ Philosophy-41 US Through the Games- 46 Squaw Valley 1960-52 Reactions to the Games- 60 2 Chapter 1: Introduction When President Jimmy Carter decided to boycott the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, it was the largest act of political interference in the history of the Olympics. It began in December of 1979 when Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan. -

Annual Report Our Mission

USA Hockey ANNUAL REPORT OUR MISSION USA Hockey provides THE FOUNDATION for the sport of ice hockey in America; helps young people BECOME LEADERS, even Olympic heroes; and CONNECTS THE GAME at every level while promoting a lifelong LOVE OF THE SPORT. Key Partners in Hockey A YEAR OF MUCH ACCOMPLISHMENT The Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games treat us to magical moments that inspire our nation and influence increased participation in our sport. And this year was no different in Sochi, Ron DeGregorio President Russia, for the 2014 Games. We won’t soon forget the grand celebration of our Paralympic Sled Hockey Team, shown nationwide on NBC, after a riveting 1-0 win over host Russia in the gold-medal game. Or the theatrics of T.J. Oshie scoring four times in a shootout, including the decisive goal in the eighth round, that led to a preliminary-round victory over Russia in one of the most anticipated men’s games in Olympic Dave Ogrean history. Executive Director And while we fell short of earning gold medals in men’s and women’s hockey, the performance of EXECUTIVE our teams will no doubt inspire more people of all ages to play our great game. COMMITTEE We’re well positioned to handle the influx of those new players thanks to the continued efforts 2013-14 across all areas of our organization. President 1 Safety is at the top of our priority list each and every day and we continued this year to devote Ron DeGregorio resources to research and education that affect both on- and off-ice safety. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abel, Allen (Globe and Mail), 151 Bukovac, Michael, 50 Abgrall, Dennis, 213–14 Bure, Pavel, 200, 203, 237 AHL (American Hockey League), 68, 127 Burns, Pat, 227–28 Albom, Mitch, 105 Button, Jack, and Pivonka, 115, 117 Alexeev, Alexander, 235 American Civil Liberties Union Political Calabria, Pat (Newsday), 139 Asylum Project, 124 Calgary Flames American Hockey League. see AHL (American interest in Klima, 79 Hockey League) and Krutov, 152, 190, 192 Anaheim Mighty Ducks, 197 and Makarov, 152, 190, 192, 196 Anderson, Donald, 26 and Priakin, 184 Andreychuk, Dave, 214 Stanley Cup, 190 Atlanta Flames, 16 Campbell, Colin, 104 Aubut, Marcel, 41–42, 57 Canada European Project, 42–44 international amateur hockey, 4 Stastny brothers, 48–50, 60 pre-WWII dominance, 33 Axworthy, Lloyd, 50, 60 see also Team Canada Canada Cup Balderis, Helmut, 187–88 1976 Team Canada gold, 30–31 Baldwin, Howard, 259 1981 tournament, 146–47 Ballard, Harold, 65 1984 tournament, 55–56, 74–75 Balogh, Charlie, 132–33, 137 1987 tournament, 133, 134–35, 169–70 Baltimore Skipjacks (AHL), 127 Carpenter, Bob, 126 Barnett, Mike, 260 Caslavska, Vera, 3 Barrie, Len, 251 Casstevens, David (Dallas Morning News), 173 Bassett, John F., Jr., 15 Catzman, M.A., 23, 26–27 Bassett, John W.H., Sr., 15 Central Sports Club of the Army (formerly Bentley, Doug, 55 CSKA), 235 Bentley, Max, 55 Cernik, Frank, 81 Bergland,Tim, 129 Cerny, Jan, 6 Birmingham Bulls (formerly Toronto Toros), Chabot, John, 105 19–20, 41 Chalupa, Milan, 81, 114 Blake, Rob, 253 Chara, Zdeno, 263 Bondra, Peter, 260 Chernykh, -

NCAA Men's Ice Hockey Records

DIVISION I 1 Men’s Ice Hockey DIVISION I Team Results Championship Championship Year Champion (Record) Coach Score Runner-Up Site Game Attendance Total Attendance 1948 ................. Michigan (20-2-1) Vic Heyliger 8-4 Dartmouth Colorado Springs, Colo. 2,700 — 1949 ................. Boston College (21-1) John “Snooks” Kelley 4-3 Dartmouth Colorado Springs, Colo. — — 1950 ................. Colorado Col. (18-5-1) Cheddy Thompson 13-4 Boston U. Colorado Springs, Colo. 3,000 — 1951 ................. Michigan (22-4-1) Vic Heyliger 7-1 Brown Colorado Springs, Colo. — — 1952 ................. Michigan (22-4) Vic Heyliger 4-1 Colorado Col. Colorado Springs, Colo. — — 1953 ................. Michigan (17-7) Vic Heyliger 7-3 Minnesota Colorado Springs, Colo. 2,700 — 1954 ................. Rensselaer (18-5) Ned Harkness 5-4 (ot) Minnesota Colorado Springs, Colo. — — 1955 ................. Michigan (18-5-1) Vic Heyliger 5-3 Colorado Col. Colorado Springs, Colo. 2,700 — 1956 ................. Michigan (20-2-1) Vic Heyliger 7-5 Michigan Tech Colorado Springs, Colo. — — 1957 ................. Colorado Col. (25-5) Thomas Bedecki 13-6 Michigan Colorado Springs, Colo. — — 1958 ................. Denver (24-10-2) Murray Armstrong 6-2 North Dakota Minneapolis 7,878 — 1959 ................. North Dakota (20-10-1) Bob May 4-3 (ot) Michigan St. Troy, N.Y. — — 1960 ................. Denver (27-4-3) Murray Armstrong 5-3 Michigan Tech Boston — — 1961 ................. Denver (30-1-1) Murray Armstrong 12-2 St. Lawrence Denver 5,363 — 1962 ................. Michigan Tech (29-3) John MacInnes 7-1 Clarkson Utica, N.Y. 4,210 — 1963 ................. North Dakota (22-7-3) Barry Thorndycraft 6-5 Denver Boston 4,200 — 1964 ................. Michigan (24-4-1) Allen Renfrew 6-3 Denver Denver 5,296 — 1965 ................ -

2012 Hockey Conference Program

Putting it on Ice III: Constructing the Hockey Family Abstracts Carly Adams & Hart Cantelon University of Lethbridge Sustaining Community through High Performance Women’s Hockey in Warner, Alberta Canada is becoming increasingly urbanized with small rural communities subject to amalgamation or threatened by decline. Statistics Canada data indicate that by 1931, for the first time in Canadian history, more citizens (54%) lived in urban centre than rural communities. By 2006, this percentage had reached 80%. This demographic shift has serious ramifications for small rural communities struggling to survive. For Warner, a Southern Alberta agricultural- based community of approximately 380 persons, a unique strategy was adopted to imagine a sense of community and to allow its residents the choice to remain ‘in place’ (Epp and Whitson, 2006). Located 65 km south of Lethbridge, the rural village was threatened with the potential closure of the consolidated Kindergarten to Grade 12 school (ages 5-17). In an attempt to save the school and by extension the town, the Warner School and the Horizon School Division devised and implemented the Warner Hockey School program to attract new students to the school and the community. By 2003, the Warner vision of an imagined community (Anderson, 1983) came to include images of high performance female hockey, with its players as visible celebrities at the rink, school, and on main street. The purpose of this paper is to explore the social conditions in rural Alberta that led to and influenced the community of Warner to take action to ensure the survival of their local school and town.