Series Books, Decade by Decade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2008

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2008 Juvenile Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Compact Discs 100 - Philosophy & Psychology DVD Videos/Videocassettes 200 - Religion E Audiocassettes 300 - Social Sciences E Audiovisual Materials 400 - Language E Books 500 - Science E CD-ROMs 600 - Technology E Compact Discs 700 - Art E DVD Videos/Videocassettes 800 - Literature E Foreign Language 900 - Geography & History E New Additions Audiocassettes Fiction Audiovisual Materials Foreign Languages Biographies Graphic Novels CD-ROMs Large Print Fiction Call # Author Title J FIC/AVI Avi, 1937- Midnight magic J FIC/BALLIETT Balliett, Blue, 1955- Chasing Vermeer J FIC/BALLIETT Balliett, Blue, 1955- The Wright 3 J FIC/BARROWS Barrows, Annie. Ivy + Bean take care of the babysitter J FIC/BARROWS 3-4 Barrows, Annie. Ivy + Bean and the ghost that had to go J FIC/BARROWS 3-4 Barrows, Annie. Ivy + Bean break the fossil record J FIC/BARROWS 3-4 Barrows, Annie. The magic half J FIC/BASE Base, Graeme. The discovery of dragons J FIC/BASE Base, Graeme. The eleventh hour : a curious mystery J FIC/BAUER Bauer, Sepp. The Christmas rose J FIC/BAUM Baum, L. Frank The marvelous land of Oz : being an account of the further adventures J FIC/BELL 3-4 Bell, Krista. If the shoe fits J FIC/BENTON 3-4 Benton, Jim. Attack of the 50-ft. Cupid J FIC/CAPOTE Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. A Christmas memory J FIC/CHRONICLES The chronicles of Narnia : the lion the witch and the wardrobe J FIC/CLEMENTS Clements, Andrew, 1949- No talking J FIC/CLEMENTS Clements, Andrew, 1949- Room one : a mystery or two J FIC/COLFER Colfer, Eoin. -

Series Books Through the Lens of History by David M

Series Books Through the Lens of History by David M. Baumann This article first appeared in The Mystery and Adventure Series Review #43, summer 2010 Books As Time Machines It was more than half a century ago that I learned how to type. My parents had a Smith-Corona typewriter—manual, of course—that I used to write letters to my cousins. A few years later I took a “typing class” in junior high. Students were encouraged to practice “touch typing” and to aim for a high number of “words per minute”. There were distinctive sounds associated with typing that I can still hear in my memory. I remember the firm and rapid tap of the keys, much more “solid” than the soft burr of computer “keyboarding”. A tiny bell rang to warn me that the end of the line was coming; I would finish the word or insert a hyphen, and then move the platen from left to right with a quick whirring ratchet of motion. Frequently there was the sound of a sheet of paper being pulled out of the machine, either with a rip of frustration accompanied by an impatient crumple and toss, or a careful tug followed by setting the completed page aside; then another sheet was inserted with the roll of the platen until the paper was deftly positioned. Now and then I had to replace a spool of inked ribbon and clean the keys with an old toothbrush. Musing on these nearly vanished sounds, I put myself in the place of the writers of our series books, nearly all of whom surely wrote with typewriters. -

A Dark Horse Series the Ted Wilfords by David M

A Dark Horse Series The Ted Wilfords by David M. Baumann January-February 2006 The first form of this article appeared in The Mystery and Adventure Series Review, #39, Summer 2006. It was revised June 10, 2007 to incorporate the addition of the first two books in proper sequence and to add more information about the author. It was revised again November 8, 2010 to update information about the availability of the books. 9,545 words For copies of this astonishingly excellent series book fanzine and information on subscriptions (free—donation expected), contact: Fred Woodworth The Mystery and Adventure Series Review P. O. Box 3012 Tucson, AZ 85702 s I cast my eyes over the collection of books that jams my shelves, I make out forty different series. When I numbered them for this article, I was surprised at how many there Awere. I also observed that, of these forty series, only ten of them, or precisely one-fourth, are series that I decided to collect on my own. Fully thirty others I owe to the recommendation of someone else. Jim Ogden led me to Wynn & Lonny. Jon Cooper suggested that I collect Dig Allen. Steve Servello introduced me to Christopher Cool. Rocco Musemeche and Tim Parker urged me to collect several series from the 1910s-1930s. Several of my favorite series came from recommendations made by Fred Woodworth. In the fall of 2005, I collected the Ted Wilford series at his suggestion. I had never heard of this series, and in more than fifteen years of collecting and occasionally hobnobbing with other collectors in person or by various means of correspondence, no one else had ever mentioned it before. -

THE YELLOW FEATHER MYSTERY by FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 33 in the Hardy Boys Series

THE YELLOW FEATHER MYSTERY By FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 33 in the Hardy Boys series. This is the 1953 original text. In the 1953 original, the Hardy Boys go to the Woodson Academy to solve the mystery of a missing will. The 1971 revision is slightly altered. The Hardy Boys series by Franklin W. Dixon, the first 58 titles. The first year is the original year. The second is the year it was revised. 01 The Tower Treasure 1927, 1959 02 The House on the Cliff 1927, 1959 03 The Secret of the Old Mill 1927, 1962 04 The Missing Chums 1927, 1962 05 Hunting for Hidden Gold 1928, 1963 06 The Shore Road Mystery 1928, 1964 07 The Secret of the Caves 1929, 1965 08 The Mystery of Cabin Island 1929, 1966 09 The Great Airport Mystery 1930, 1965 10 What Happened at Midnight 1931, 1967 11 While the Clock Ticked 1932, 1962 12 Footprints Under the Window 1933, 1962 13 The Mark on the Door 1934, 1967 14 The Hidden Harbor Mystery 1935, 1961 15 The Sinister Sign Post 1936, 1968 16 A Figure in Hiding 1937, 1965 17 The Secret Warning 1938, 1966 18 The Twisted Claw 1939, 1964 19 The Disappearing Floor 1940, 1964 20 The Mystery of the Flying Express 1941, 1968 21 The Clue of the Broken Blade 1942, 1969 22 The Flickering Torch Mystery 1943, 171 23 The Melted Coins 1944, 1970 24 The Short Wave Mystery 1945, 1966 25 The Secret Panel 1946, 1969 26 The Phantom Freighter 1947, 1970 27 The Secret of Skull Mountain 1948, 1966 28 The Sign of the Crooked Arrow 1949, 1970 29 The Secret of the Lost Tunnel 1950, 1968 30 The Wailing Siren Mystery 1951, 1968 31 The Secret of Wildcat -

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2008

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2008 Juvenile Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Compact Discs 100 - Philosophy & Psychology DVD Videos/Videocassettes 200 - Religion E Audiocassettes 300 - Social Sciences E Audiovisual Materials 400 - Language E Books 500 - Science E CD-ROMs 600 - Technology E Compact Discs 700 - Art E DVD Videos/Videocassettes 800 - Literature E Foreign Language 900 - Geography & History E New Additions Audiocassettes Fiction Audiovisual Materials Foreign Languages Biographies Graphic Novels CD-ROMs Large Print Fiction Call # Author Title J FIC/AMATO Amato, Mary. Stinky and successful : the Riot brothers never stop J FIC/ARMSTRONG Armstrong, Alan W., 1939- Raleigh's page J FIC/BAKER Baker, E. D. Dragon's breath J FIC/BARRY Barry, Dave. Peter and the secret of Rundoon J FIC/BAUER Bauer, Sepp. The Christmas rose J FIC/BELTON Belton, Sandra. The tallest tree J FIC/BERGEN 3-4 Bergen, Lara. A masterpiece for Bess J FIC/BERKELEY Berkeley, Jon. The tiger's egg J FIC/BLUME Blume, Lesley M. M. The rising star of Rusty Nail J FIC/BROWN 3-4 Brown, Marc Tolon. Locked in the library! J FIC/BYNG Byng, Georgia. Molly Moon, Micky Minus, & the Mind Machine J FIC/BYNG Byng, Georgia. Molly Moon's incredible book of hypnotism J FIC/CAMPBELL Campbell, Julie, 1908- The red trailer mystery J FIC/CHRISTOPHER 3-4 Christopher, Matt. Olympic dream J FIC/CHRONICLES The chronicles of Narnia : the lion the witch and the wardrobe : the movie storybook J FIC/CLEARY Cleary, Beverly. Henry Huggins J FIC/COLLINS Collins, Suzanne. Gregor and the marks of secret J FIC/COULOUMBIS Couloumbis, Audrey. -

THE SECRET PANEL by FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 25 in the Hardy Boys Series

THE SECRET PANEL By FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 25 in the Hardy Boys series. This is the original 1946 text. In the 1946 original, the Hardy Boys solve a kidnapping mystery at the weird Mead House, which lacks both door knobs and hinges. The 1969 revision is altered. The Hardy Boys series by Franklin W. Dixon, the first 58 titles. The first year is the original year. The second is the year it was revised. 01 The Tower Treasure 1927, 1959 02 The House on the Cliff 1927, 1959 03 The Secret of the Old Mill 1927, 1962 04 The Missing Chums 1927, 1962 05 Hunting for Hidden Gold 1928, 1963 06 The Shore Road Mystery 1928, 1964 07 The Secret of the Caves 1929, 1965 08 The Mystery of Cabin Island 1929, 1966 09 The Great Airport Mystery 1930, 1965 10 What Happened at Midnight 1931, 1967 11 While the Clock Ticked 1932, 1962 12 Footprints Under the Window 1933, 1962 13 The Mark on the Door 1934, 1967 14 The Hidden Harbor Mystery 1935, 1961 15 The Sinister Sign Post 1936, 1968 16 A Figure in Hiding 1937, 1965 17 The Secret Warning 1938, 1966 18 The Twisted Claw 1939, 1964 19 The Disappearing Floor 1940, 1964 20 The Mystery of the Flying Express 1941, 1968 21 The Clue of the Broken Blade 1942, 1969 22 The Flickering Torch Mystery 1943, 171 23 The Melted Coins 1944, 1970 24 The Short Wave Mystery 1945, 1966 25 The Secret Panel 1946, 1969 26 The Phantom Freighter 1947, 1970 27 The Secret of Skull Mountain 1948, 1966 28 The Sign of the Crooked Arrow 1949, 1970 29 The Secret of the Lost Tunnel 1950, 1968 30 The Wailing Siren Mystery 1951, 1968 31 The Secret of -

The Clue of the Screeching Owl by Franklin W

-: Converted by FileMerlin :- THE CLUE OF THE SCREECHING OWL BY FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 41 in the Hardy Boys series, This is the original 1962 text. The Hardy Boys and Chet are in the Pocono Mountains to locate Mr. Hardy's missing friend, a retired police captain, and solve the mystery of spooky Black Hollow. As of 2002, this is the only version of this book. The Hardy Boys series by Franklin W. Dixon, the first 58 titles. The first year is the original year. The second is the year it was revised. 01 The Tower Treasure 1927, 1959 02 The House on the Cliff 1927, 1959 03 The Secret of the Old Mill 1927, 1962 04 The Missing Chums 1927, 1962 05 Hunting for Hidden Gold 1928, 1963 06 The Shore Road Mystery 1928, 1964 07 The Secret of the Caves 1929, 1965 08 The Mystery of Cabin Island 1929, 1966 09 The Great Airport Mystery 1930, 1965 10 What Happened at Midnight 1931, 1967 11 While the Clock Ticked 1932, 1962 12 Footprints Under the Window 1933, 1962 13 The Mark on the Door 1934, 1967 14 The Hidden Harbor Mystery 1935, 1961 15 The Sinister Sign Post 1936, 1968 16 A Figure in Hiding 1937, 1965 17 The Secret Warning 1938, 1966 18 The Twisted Claw 1939, 1964 19 The Disappearing Floor 1940, 1964 20 The Mystery of the Flying Express 1941, 1968 21 The Clue of the Broken Blade 1942, 1969 22 The Flickering Torch Mystery 1943, 171 23 The Melted Coins 1944, 1970 24 The Short Wave Mystery 1945, 1966 25 The Secret Panel 1946, 1969 26 The Phantom Freighter 1947, 1970 27 The Secret of Skull Mountain 1948, 1966 28 The Sign of the Crooked Arrow 1949, 1970 29 -

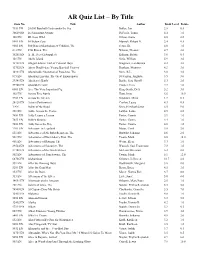

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

AR Quiz List – By Title Quiz No. Title Author Book Level Points 7351 EN 20,000 Baseball Cards under the Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue DePaola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8001 EN 50 Below Zero Munsch, Robert N. 2.4 0.5 9001 EN 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 16201 EN A...B...Sea (Crabapples) Kalman, Bobbie 3.6 0.5 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 5.9 3.0 13701 EN Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Wagoner, Jean Brown 4.2 3.0 13702 EN Abner Doubleday: Young Baseball Pioneer Dunham, Montrew 4.2 3.0 14931 EN Abominable Snowman of Pasadena, The Stine, R.L. 3.0 3.0 815 EN Abraham Lincoln: The Great Emancipator Stevenson, Augusta 3.5 3.0 29341 EN Abraham's Battle Banks, Sara Harrell 5.3 2.0 39788 EN Absolutely Lucy Cooper, Ilene 2.7 1.0 6001 EN Ace: The Very Important Pig King-Smith, Dick 5.2 3.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 6.6 10.0 7201 EN Across the Stream Ginsburg, Mirra 1.7 0.5 28128 EN Actors (Performers) Conlon, Laura 4.3 0.5 1 EN Adam of the Road Gray, Elizabeth Janet 6.5 9.0 301 EN Addie Across the Prairie Lawlor, Laurie 4.9 4.0 7651 EN Addy Learns a Lesson Porter, Connie 3.9 1.0 7653 EN Addy's Surprise Porter, Connie 4.4 1.0 7652 EN Addy Saves the Day Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 7701 EN Adventure in Legoland Matas, Carol 3.8 2.0 451 EN Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein, The Hurwitz, Johanna 4.6 2.0 501 EN Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Twain, Mark 6.6 18.0 401 EN Adventures of Ratman, The Weiss, Ellen 3.3 1.0 29524 EN Adventures of Sojourner, The Wunsch, Susi Trautmann 7.8 1.0 21748 EN Adventures of the Greek Heroes McLean/Wiseman 6.2 4.0 502 EN Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Twain, Mark 8.1 12.0 68706 EN Afghanistan Gritzner, Jeffrey A. -

Library Leaf September Grades 3-4-5 Page 2

Want to find some great books to read on the computer? On the library website click on this link: Books recently added to our library Fic Han True (--sort of) by Katherine Hannigan 621.042 Wea Onion juice, poop, and other surprising sources of alternative energy. Fic Cle Keepers of the School series by Andrew Clements We the Children Fear Itself Fic Osb Magic Tree House Series by Mary Pope Osborne Dogs in the dead of night Fic Dix Hardy Boys Mysteries series by Franklin Dixon Farming fear, The house on the cliff, Hunting for hidden gold, The secret of the old mill, The shore road mystery, The tower treasure The missing chums Fic Rus Dork Diary series by Rachel Russell Tales from a not-so-talented pop star (#3) Fic Gre Maximum Boy series by Dan Greenburg Super Hero or Super Thief? (#3) Hans and Margret escaped from Paris on ______________. Fic Gre Zach Files series by Dan Greenburg How many languages did Hans know? _______________- Through the Medicine Cabinet Where did Hans and Margret live for a while with their pet monkeys? _______ E Arn Fly Guy vs. the flyswatter! by Tedd Arnold Hans was ____________ about many things when he was growing up. E Lew The Lion, the witch and the wardrobe by CS Lewis retold by H. Oram What was the original name of Curious George in Paris? __________ E Pal How will I get to school this year? by Jerry Pallotta E Tho Hear comes the big, mean dust bunny! by Jan Thomas Short for Reyersbach, Rey was the name Hans used as his __________. -

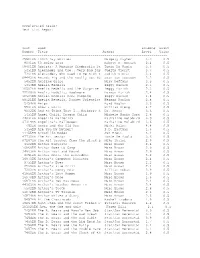

Accelerated Reader Test List Report

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 35821EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 3.0 0.5 8001EN 50 Below Zero Robert N. Munsch 2.4 0.5 59601EN Adelita: A Mexican Cinderella St Tomie De Paola 3.3 0.5 5451EN Alexander and the...Very Bad Day Judith Viorst 3.7 0.5 7301EN Alexander, Who Used to Be Rich L Judith Viorst 3.4 0.5 88443EN Amanda Pig and the Really Hot Da Jean Van Leeuwen 2.2 0.5 5452EN Amazing Grace Mary Hoffman 3.5 0.5 5453EN Amelia Bedelia Peggy Parish 2.5 0.5 10502EN Amelia Bedelia and the Surprise Peggy Parish 2.3 0.5 72206EN Amelia Bedelia, Bookworm Herman Parish 2.4 0.5 10503EN Amelia Bedelia Goes Camping Peggy Parish 1.8 0.5 89521EN Amelia Bedelia, Rocket Scientist Herman Parish 2.8 0.5 5454EN Amigo Byrd Baylor 3.6 0.5 5501EN Amos & Boris William Steig 4.7 0.5 9002EN And to Think That I...Mulberry S Dr. Seuss 3.6 0.5 5455EN Angel Child, Dragon Child Michele Maria Sura 2.8 0.5 44031EN Angelina Ballerina Katharine Holabird 3.9 0.5 47319EN Angelina's Halloween Katharine Holabird 3.6 0.5 652EN Annie and the Old One Miska Miles 4.4 0.5 5456EN Are You My Mother? P.D. Eastman 1.6 0.5 11155EN Armadillo Rodeo Jan Brett 3.4 0.5 47730EN The Art Lesson Tomie De Paola 3.6 0.5 87267EN The Art Teacher from the Black L Mike Thaler 2.9 0.5 6102EN Arthur Babysits Marc Brown 2.4 0.5 16966EN Arthur Goes to Camp Marc Brown 2.9 0.5 34903EN Arthur Lost and Found Marc Brown 2.6 0.5 6051EN Arthur Meets the President Marc -

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 9.0 EN 69347 Paparchontis, 100 Leaders Who Changed the World 9.8 9.0 EN Kathleen 69348 Crompton, Samuel 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World 9.1 9.0 EN Willard 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Wardlaw, Lee 3.9 5.0 EN 61265 12 Again Corbett, Sue 4.9 8.0 EN 39863 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 5.1 6.0 EN 11101 16th Century Mosque, A MacDonald, Fiona 7.7 1.0 EN 8251 EN 18-Wheelers (Cruisin') Maifair, Linda Lee 5.2 1.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 2.0 EN 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 1.0 EN 56506 1960s: The Age of Rock (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.2 1.0 EN 56507 1970s: Turbulent Times (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 7.8 1.0 EN 9801 EN 1980 U.S. Hockey Team (Olympic Gold) Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 950 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Verne, Jules 11.0 30.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Pacemaker) Verne/Clare 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 34791 2001: A Space Odyssey Clarke, Arthur C. 9.0 12.0 EN 34787 2010: Odyssey Two Clarke, Arthur C. -

Read Book Hunting for Hidden Gold

HUNTING FOR HIDDEN GOLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Franklin W. Dixon | 180 pages | 14 Oct 2000 | Penguin Young Readers Group | 9780448089058 | English | New York, NY, United States Hunting for Hidden Gold #5 by Franklin W. Dixon: | : Books Inspired by Your Browsing History. Hardy Boys the Great Airport Mystery. Hardy Boys What Happened at Midnight. Hardy Boys the Secret of the Caves. The Mystery of Cabin Island 8. The Shore Road Mystery 6. Hardy Boys While the Clock Ticked. Hardy Boys Footprints Under the Window. Hardy Boys the Mark on the Door. Hardy Boys the Hidden Harbor Mystery. Hardy Boys the Sinister Signpost. Hardy Boys a Figure in Hiding. Hardy Boys the Disappearing Floor. Hardy Boys the Secret Warning. Hardy Boys the Twisted Claw. Hardy Boys the Mystery of the Spiral Bridge. Hardy Boys Danger on Vampire Trail. Hardy Boys the Clue of the Broken Blade. Hardy Boys the Melted Coins. Hardy Boys the Haunted Fort. Hardy Boys the Mystery of the Aztec Warrior. Of course, the characters are thin, which is common in the series. Most of the regulars, even their father, only have cameos. As a kid, I never really noticed the dated elements, but they are very obvious to me now. Overall, this is another fun book that kill entertain middle graders. Even adults will enjoy the nostalgia of Hunting for Hidden Gold. Labels: book , kids , mystery. Katherine P April 26, at PM. Newer Post Older Post Home. Subscribe to: Post Comments Atom. The Hardy Boys head to Montana to help their father who had been working on a case and broke his ribs.