'Men Not Allowed': the Social Construction and Rewards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

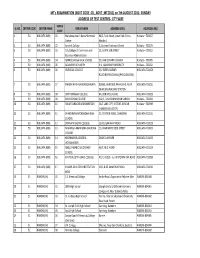

FINAL LIST of TEST CENTERS.Xlsx

MT's EXAMINATION (ADVT CODE ‐CIL_ADVT_MT2011) on 7th AUGUST 2011‐ SUNDAY ADDRESS OF TEST CENTRES‐ CITY WISE VENUE SL NO. CENTER CODE CENTER NAME VENUE NAME ADDRESS LINE1 ADDRESS LINE2 CODE 1 50 KOLKATA (WB) 01 Mahatma Aswini Datta Memorial 94/2, Park Street, (near Park Circus Kolkata – 700017 Centre Maidan) 2 50 KOLKATA (WB) 02 Sanskrit College 1, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata – 700073 3 50 KOLKATA (WB) 03 City College of Commerce and 13, SURYA SEN STREET Kolkata – 700012 Business Administration 4 50 KOLKATA (WB) 04 NARKELDANGA HIGH SCHOOL 50, KABI SUKANTA SARANI Kolkata – 700085 5 50 KOLKATA (WB) 05 JADAVPUR VIDYAPITH P.O. JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY Kolkata – 700032 6 50 KOLKATA (WB) 06 GURUDAS COLLEGE 1/1 SUREN SARKAR KOLKATA‐700054 ROAD,NARKELDANGA (PHOOLBAGAN) 7 50 KOLKATA (WB) 07 PARESH NATH BALIKA BIDYALAYA 86A&B, BANERJEE PARA LANE, NEAR KOLKATA‐700031 DHAKURIA RAILWAY STATION 8 50 KOLKATA (WB) 08 CHITTARANJAN COLLEGE 8A, BENIATOLA LANE KOLKATA‐700009 9 50 KOLKATA (WB) 09 RAMMOHAN COLLEGE 102/1, RAJA RAMMOHAN SARANI Kolkata – 700009 10 50 KOLKATA (WB) 10 SUKANTANAGAR VIDYANIKETAN SALT LAKE CITY, SECTOR ‐4 (NEAR Kolkata – 700098 CHINRIGHATA STOP) 11 50 KOLKATA (WB) 11 DHAKURIA RAMCHANDRA HIGH 10, STATION ROAD, DHAKURIA KOLKATA‐700031 SCHOOL 12 50 KOLKATA (WB) 12 SIVANATH SASTRI COLLEGE 23/49, GARIAHAT ROAD KOLKATA‐700029 13 50 KOLKATA (WB) 13 MAHARAJA MANINDRA CHANDRA 20, RAMKANTO BOSE STREET KOLKATA‐700003 COLLEGE 14 50 KOLKATA (WB) 14 KRISHNAPUR ADARSHA DUM DUM PARK KOLKATA‐700055 VIDYAMANDIR 15 50 KOLKATA (WB) 15 ANGLO ARABIC SECONDARY 46/7, M.G. ROAD KOLKATA‐700009 SCHOOL 16 50 KOLKATA (WB) 16 EAST CALCUTTA GIRLS COLLEGE P237, BLOCK ‐ B, LAKETOWN LINK ROAD KOLKATA‐700089 17 50 KOLKATA (WB) 17 KUMAR ASHUTOSH INSTITUTION 10/1 & 8E, DUM DUM ROAD KOLKATA‐700030 BOYS 19 51 RANCHI (JH) 01 S.S. -

Kolkata Stretcar Track

to BANDEL JN. and DANKUNI JN. to NAIHATI JN. to BARASAT JN. Kolkata 22./23.10.2004 M DUM DUM Streetcar track map: driving is on the left r in operation / with own right-of-way the second track from the right tracks seeming to be operable e is used to make the turns of the regular passenger trains track trunks which are not operable v other routes in 1996 according to Tasker i other suspended routes according to CTC map TALA 11 [13] R actual / former route number according to CTC ULTADANGA ROAD Suburban trains and ‘Circular Railway’ according to Narayanan: Galif [12] i BELGATCHIA in operation under construction l Street [13] 1 2 11 PATIPUKUR A.P.C. Rd[ 20 ] M Note: The route along the Hugly River can’t be confirmed by my own g 12 Belgatchia observations. Bagbazar SHYAM BAZAR R.G. Kar Rd u BAG BAZAR M M metro railway pb pedestrian bridge 1 2 [4] 11 H Shyambazar BIDHAN NAGAR ROAD pb TIKIAPARA [8] 5 SOVA SOVA BAZAR – M BAZAR 6 AHIRITOLA Bidhan Nagar to PANSKURA JN. Aurobinda Sarani 17 housing block [4] 20 20 [12] [13] [ 12 ] 17 loop Esplanade [10] Rabindra Setu Nimtala enlargement (Howrah Bridge) pb [4] 1 [8] GIRISH 2 Howrah [10] M PARK 5 BURRA 6 15 Bidhan Sarani Rabindra Sarani 11 BAZAR 11 12 20 [21] [26] V.I.P. Rd 15 HOWRAH 11 12 M.G. 30Rd MAHATMA Maniktala Main Rd RAILWAY GANDHI 20 30 Acharya Profullya Chandra Rd STATION M ROAD M.G. Rd 20 Howrah [16] 17 17 Northbound routes are [12] [13] [16] M turning counterclockwise, Bridge 15 Mahatma Gandhi Rd 20 20 southbound routes are [4] 11 12 15 17 [ 12 ] 17 ESPLANADE 12 20 turning clockwise. -

Bengal Abasan Urban Sunshine - E M Bypass, K… Residential Apartment Flats & Complex Residential Flats with Lift, Power Backup, Car Parking

https://www.propertywala.com/bengal-abasan-urban-sunshine-kolkata Bengal Abasan Urban Sunshine - E M Bypass, K… Residential Apartment Flats & Complex Residential Flats With Lift, Power Backup, Car Parking. Flat Size Are 1224sq-ft & 1226 sq-ft.,3BHK With 3 Sides Open. Project ID : J290614911 Builder: Bengal Abasan Builders Properties: Apartments / Flats Location: 1403, E M Bypass, Kolkata (West Bengal) Completion Date: Dec, 2012 Status: Started Description Bengal Abasan Builders : has been formed with an objective to develop quality infrastructure and real estate projects. The company strongly believe in extending total quality at the most granular level of each project. each project incorporate the most arduous standards of materials and construction quality in order to endow it with one-in-lifetime investment value. We consider each project to be a fusion of real estate best practices, innovation and total commitment to every individual customer. For us work is worship and therefore we emphasize on giving better quality in our forth coming projects. Today, Bengal Abasan Builder is taking giant leaps and exploring new horizons in construction & real estate. As a real estate company we have been redefining the standards of real estate and with our years of experience we offer a wide range of services to fulfill our clients need. Urban Sunshine : presents ground +3 residential flats with lift, power backup, car parking etc. Near kalikapur bus stop, on em bypass. Flat size are 1224sqft and 1226sqft., 3bhk with 3 sides open. Rate 3000/- per sq-ft. If you are seeking a dream home that combines the twin benefits of a reclusive nest on one hand and on the other offers superior connectivity to the major city center. -

Saraswati Green Ville

https://www.propertywala.com/saraswati-green-ville-kolkata Saraswati Green Ville - Sonarpur Station Road,… 3 & 4 BHK apartments available at Saraswati Green Ville Saraswati Green Ville presented by Saraswati Infracon India Ltd. with 3 & 4 BHK apartments available at Sonarpur, Kolkata Project ID : J661118999 Builder: Saraswati Infracon India Ltd. Location: Saraswati Green Ville, Sonarpur Station Road area, Kolkata (West Bengal) Completion Date: Jun, 2015 Status: Started Description Saraswati Green Ville is a new launch by Saraswati Infracon India Ltd. The project is located in amid-st of the greens of snapper, in the outskirts of Kolkata. The project is away from the hustle and bustle of the city life, the project is situated on a vast stretch of land offers a perfect life - a life in a dream home possessing state -of -the -art club class amenities in the lap of Nature. Amenities Garden Swimming Pool Play Area Health Facilities 24Hr Backup Maintenance Staff Security Intercom Club House Rain Water Harvesting Wifi Gymnasium Indoor Games Community Hall Saraswati Infracon India Limited, was established in 2008 in order to achieve the aim of providing turnkey solutions in construction and infrastructural engineering, particularly in the areas of civil engineering services and construction management solutions. Although a young company, it is manned by qualified professionals who have many years of experience in their chosen area as well as a passion and the commitment to work as a team for timely completion of projects. Features Luxury Features -

KOLKATA the WATER-WASTE PORTRAIT Neglect Has Led to Disrepair and Breakdown of Water Distribution and Wastewater Exit

KOLKATA THE WATER-WASTE PORTRAIT Neglect has led to disrepair and breakdown of water distribution and wastewater exit. Skewed policies have led to encroachment of the natural waste treatment engines, the wetlands. Groundwater is dipping – Kolkata has much PALTA to contend with in the coming years WTP (30 km) Water pumping station (PS) Effluent Dumdum Ramlila discharged to Water treatment plant (WTP) Bagan Bajola Canal Drainage Basin BANGUR Sewage treatment plant (STP) TALLAH PS STP Disposal of sewage Kes ht l Shyambazar o na pu a Circular Canal Circular r C Waterways r Shobha Keshtopur Canal e Bazar Salt v lake i JORABAGAN r National WTP Rubber Narkel y Factory l Victoria Danga h Memorial Circular Canal g East DWF channel o o Fort Chingrighata Kolkata H William DHAPA Park Circus WTP Wetlands GARDEN REACH WATGUNGE DWF channel Bhawanipur Intake point for WTP & STP WTP Garden Reach WTP Ballygunge Manikali Kasba ca n a ullah v e r l Dhakuria r i y l Jodhpur Park Rajarghat NTolly h Discharged to g Hooghly River o Jadavpur o Panchanangram Canal Discharged to Mahesh Tollygunge H Kolkata Tala Regent Behala Park Stormwater Budge BAGHA JATIN Channel Budge STP C n SOUTH o Lead channel h i Churial diversion u r s SUBURBAN ial C anal n e t EAST STP x e l ia ur Kalagachia Canal Ch Discharged to Effluent discharged Hooghly river to Churial Canal Drainage Basin Source: Anon 2011, 71-City Water-Excreta Survey, 2005-06, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi 390 WEST BENGAL THE CITY Municipal area (Kolkata Municipal Corporation) 187 sq km Total area (Kolkata Metropolitan Area) 1,750 sq km Kolkata Population (2005) of KMC 5.4 million Population (2011) of KMC, as projected in 2005-06 6.2 million THE WATER Demand ome 315 years ago, British merchants had dropped anchor at Total water demand as per city agency 925 MLD the small hamlet of ‘Kolikata’ on the eastern corner of the Per capita water demand as per city agency 170 LPCD Indian sub-continent. -

Prepaid Taxi Fare

Prepaid Taxi Fare Sale Rate (4.30 A.M. To 10.30 P.M. Destination 10.30 P.M.) To 4.30 A.M. 206 Bus Stand 190.00 215.00 30A Bus Stand 170.00 170.00 A.J.C. Bose Road(M.Park) 120.00 135.00 Adyapith 190.00 215.00 Air Port Gate-2 240.00 270.00 Airport 21/2 Nimta 265.00 300.00 Airport Gate No. 1 240.00 270.00 Airport Via Bally Bridge & Belgharia Xpress Way. 300.00 340.00 Airport Via Vip Road. 240.00 270.00 Air-Port-Gate-3 265.00 340.00 Ajay Nagar. 265.00 300.00 Akansha Building New Town. 265.00 300.00 Alam Bazar Via Bally Bridge. 190.00 215.00 Alampur Howrah.. 265.00 300.00 Alimuddin St. 120.00 135.00 Alipore Command Hospital. 170.00 190.00 Alipore Sbi. 170.00 190.00 Alipur Zoo(Via 2Nd Hb) 170.00 190.00 Alochhaya Cinema Hall. 120.00 135.00 Aloka Cinema. 65.00 70.00 Amherst St 90.00 100.00 Amtala Via 2Nd Hb. 410.00 465.00 Anandapur. 240.00 270.00 Andul Howrah. 215.00 245.00 Ankara Fatak. 265.00 300.00 Ankara Rabindranagar. 265.00 300.00 Ankara Santoshpur. 265.00 300.00 Apollo Glenagles Hospital. 190.00 215.00 Aquatica 300.00 340.00 Ariadaha. 190.00 215.00 Ashok Nagar Park 215.00 245.00 Athghora. 265.00 300.00 Athpur Op. 445.00 505.00 Avani Mall. 65.00 70.00 Axis Mall. -

1 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for Rent in Khudiram Pally, Kolkata (P48073513)

https://www.propertywala.com/P48073513 Home » Kolkata Properties » Residential properties for rent in Kolkata » Apartments / Flats for rent in Khudiram Pally, Kolkata » Property P48073513 1 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for rent in Khudiram Pally, Kolkata 3,500 1BHK Builder Floor In KHUDIRAM PALLY, Advertiser Details Kolkata Aq-63/9, Khudiram Pally, Kolkata - 700065 (West Bengal) Area: 27.87 SqMeters ▾ Bedrooms: One Bathrooms: One Monthly Rent: 3,500 Rate: 126 per SqMeter +15% Available: Immediate/Ready to move Description Scan QR code to get the contact info on your mobile Newly built 300 sqft carpet area house at khudiram pally, t p road. Sarsuna. Pictures 1 bed room, 1 kitchen come dinnig 1 attached bathroom with a big banker store space newly built When you call, don't forget to mention that you saw this ad on PropertyWala.com. Features Other features Kitchen Bedroom Carpet Area: 27.87 sq.m. South Facing Floor: Ground of 2 Floors 0 to 1 year old Cement Flooring Furnishing: Semifurnished Reserved Parking Location Bedroom Dinning Room Bathroom * Location may be approximate Landmarks Public Transport Thakupukur 3a Bus Stand (<3km), TOLLYGUNGE METRO STATION (<9k…Pailan Bus Station (<5km), Tollygunge (<10km), KALIGHAT METRO STATION-GATE N…Netaji (<8km), Brace Bridge Railway Station (<8km), Jadavpur 8b Bus Stand (<12km), RABINDRA SADAN METRO STATION… Kavi Nazrul (<13km), Majerhat Railway Station (<9km), Akra Railway Station (<9km), As2 Krishna Glass Bus Station (<12km… Rabindra Sarobar Metro Station-Gate… JATIN DAS PARK METRO STATION-G…Shalimar -

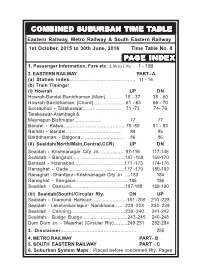

Combined Sub Combined Suburban Time Table Page

COMBINED SUBURBURBURBAN TIME TTTABLEABLEABLE Eastern Railway, Metro Railway & South Eastern Railway 1st October, 2015 to 30th June, 2016 Time Table No. 8 PPPAAAGE INDEX 1. Passenger Information, Fare etc. (E. Rly & S.E. Rly) 1 - 10B 2. EASTERN RAILWAY PART - A (a) Station Index............................................ 11 - 14 (b) Train Timings: (i) Howrah UP DN Howrah-Bandel-Barddhaman (Main)............ 15 - 37 38 - 60 Howrah-Barddhaman (Chord).......................61 - 65 66 - 70 Seoraphuli - Tarakeswar............................ 71 -73 74- 76 Tarakeswar-Arambagh & Maynapur-Bishnupur................... 77 77 Bandel - Katwa......................................... 78 -80 81 - 83 Naihati - Bandel...................................... 84 85 Barddhaman - Balgona.............................. 86 86 (ii) Sealdah(North/Main,Central,CCR) UP DN Sealdah - Krishnanagar City Jn.................. 87-116 117-146 Sealdah - Bangaon....................................147 -158 159-170 Barasat - Hasnabad..................................171 -173 174-176 Ranaghat - Gede......................................177 -179 180-182 Ranaghat - Shantipur- Krishnanagar City Jn .....183 184 Ranaghat - Bangaon....................................185 186 Sealdah - Dankuni.....................................187-188 189-190 (iii) Sealdah(South)/Circular Rly. DN UP Sealdah - Diamond Harbour.........................191 -209 210 -228 Sealdah - Lakshmikantapur- Namkhana........229 -233 234- 238 Sealdah - Canning.....................................239 -240 241-242 Sealdah -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Running on Time Domestic Work and Commuting in West Bengal, India Lauren Wilks PhD in Sociology The University of Edinburgh 2018 ii Declaration I hereby confirm that this thesis has been composed solely by myself and has not been submitted, in whole or in part, for any other degree or professional qualification. Except where stated otherwise by reference or acknowledgment, the work presented is entirely my own. Lauren Wilks Edinburgh, 5 December 2018 iii iv Table of Contents Abstract vii Lay Summary viii Acknowledgements xi List of Illustrations xiv List of Abbreviations xvi Glossary xvii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Locating Domestic Work 13 Chapter Three: Researching Domestic Work -

New Town Planning, Informality and the Geography of Disaster in Kolkata, India

THE CITY VULNERABLE: NEW TOWN PLANNING, INFORMALITY AND THE GEOGRAPHY OF DISASTER IN KOLKATA, INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Andrew Joseph Rumbach August 2011 © 2011 Andrew Joseph Rumbach THE CITY VULNERABLE: NEW TOWN PLANNING, INFORMALITY AND THE GEOGRAPHY OF DISASTER IN KOLKATA, INDIA Andrew Joseph Rumbach, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 Cities in the global South are increasingly at-risk from environmental hazards, but frameworks for understanding disaster vulnerability do not adequately explain urbanization or the role played by urban governance institutions in shaping disaster outcomes. Drawing on interview, archival, geospatial, and survey data, I argue that urbanization and the geographies of risk it produces are historically rooted and structured by political, economic, social, and institutional norms embedded in city environments. Disaster risk exists not just at multiple scales but also differentially across the city. As this dissertation demonstrates, individual and household vulnerabilities, and the norms and structural conditions that help shape them, are connected to a pattern of fractured urban development. My study is based in Kolkata and centers on new town developments, one of the most significant spatial components of urban growth in India post- Independence. In such contexts, planning is one of the central urban governance institutions and sets of practices that shape the growth of Indian cities. While planning may be spatially or temporally distant from disaster events, the trajectory of urban development that planning lays out and the settlement logic it employs are foundational in shaping future disaster events. -

Kolkata (Calcutta) 485

© Lonely Planet Publications 485 Kolkata Kolkata (Calcutta) (Calcutta) Simultaneously noble and squalid, cultured and desperate, Kolkata is a daily festival of human existence. And it’s all played out before your very eyes on teeming streets where not an inch of space is wasted. By its old spelling, Calcutta, India’s second-biggest city conjures up images of human suffering to most Westerners. But Bengalis have long been infuriated by one-sided depictions of their vibrant capital. Kolkata is locally regarded as the intellectual and cultural capital of the nation. Several of India’s great 19th- and 20th-century heroes were Kolkatans, including guru-philosopher Ramakrishna, Nobel Prize–winning poet Rabindranath Tagore and celebrated film director Satyajit Ray. Dozens of venues showcase Bengali dance, poetry, art, music, film and theatre. And while poverty certainly remains in-your-face, the dapper Bengali gentry continue to frequent grand old gentlemen’s clubs, back horses at the Calcutta Racetrack and play soothing rounds of golf at some of India’s finest courses. KOLKATA (CALCUTTA) As the former capital of British India, Kolkata retains a feast of dramatic colonial architecture, with more than a few fine buildings in photogenic states of semi-collapse. The city still has many slums but is also developing dynamic new-town suburbs, a rash of air-conditioned shopping malls and some of the best restaurants in India. This is a fabulous place to sample the mild, fruity tang of Bengali cuisine and share the city’s passion for sweets. Friendlier than India’s other mega-cities, Kolkata is really a city you ‘feel’ more than just visit.