How Will Massive Online Collaboration Impact the World of Translation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating Web Development Frameworks for Delphi

Evaluating Web Development Frameworks for Delphi Updates, links, and more embt.co/WebDev2019 #DelphiWebDev Disclaimer ❏ This content is mostly focused on 3rd party frameworks and libraries ❏ While a lot of time was spent researching, some of the information may be outdated or otherwise incorrect through an error during research ❏ Links are provided to the sources, and you are encouraged to double check all information and seek clarification ❏ Any exclusion is just an oversight or a result of limited time and space and was not an intentional indication of quality or suitability ❏ This information presented here is not intended to indicate superiority or inferiority of one library over another for any use cases ❏ Please consider this a good faith effort to represent these libraries and frameworks impartially and accurately ❏ I will reach out to the projects, companies, and developers to seek corrections and additional information. ❏ Erratas and updates will be published at embt.co/WebDev2019 Thanks! Delphi and FireMonkey: Winning Combination for Cross- Platform Development → Single Codebase → Easy-to-tailor platform specific UIs → One programming language to learn and support What about Web Apps? Delphi’s incredible productivity for building amazing apps also extends to the web! https://blog.hootsuite.com/simon-kemp-social-media/ https://blog.hootsuite.com/simon-kemp-social-media/ People spend a daily average of 6 hours & 42 minutes using the internet https://blog.hootsuite.com/simon-kemp-social-media/ ❏Different kinds of web development -

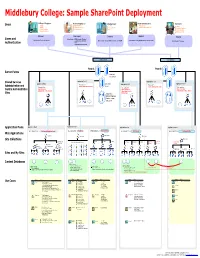

Visio-MIDD Sharepoint Architecture Design Sample.Vsd

College Colleagues Remote Employees Internal Users Farm Administrators Customers Trustees Work from Home Web Services Faculty Parents Alumni Affiliated Institutions Systems & Network Services Current Students Prospective Students External Professors Schools Abroad Staff Local Community Prospective Students Global Community Extranet Remotenet Intranet Adminet Internet Authentication = NTLM (Integrated Windows) Authentication = forms authentication using ISA Server 2006 SSO Authentication = Integrated Windows (Kerberos or NTLM) Authentication = Integrated Windows (Kerberos or NTLM) Authentication = Anonymous —or— Forms with an LDAP provider Application Pool 1 Application Pool 7 Application Pool 2 Application Pool 3 Application Pool 8 Web application: Web application: Central Administration Site Central Administration Site Web application: Web application: Web application: Shared Services Shared Services Shared Services Administration Site—Default Administration Site— Administration Site—Default PartnerWeb Application Pool 4 Application Pool 5 Application Pool 6 Application Pool 9 Web application: Intranet Applications Web application: My Sites Web application: Team Sites Web application: Intraweb Web application: Internet Site http://team <varies> http://my http://web http://www Team1 Team2 Team3 Delivered http://my/personal/<user> Handbook HR Policies Library Authoring Site Staging Site Production Site Content Collection Collection Collection HR Project from Events Management Banner, Registration Segue, etc Admissions Academics Athletics Database settings: Target size per database = TBD Database settings: Database settings: Database settings: Site size limits per site = TBD Target size per database = TBD Content Deployment Site level warning = 0 Site level warning = 0 Content Deployment Maximum number of sites = flexible Storage quota per site = TBD Maximum number of sites = 1 (one site collection per database). Maximum number of sites = 1 (one site collection per database). -

COLLABORATIVE KNOWLEDGE EVALUATION with a SEMANTIC WIKI Wikidesign

COLLABORATIVE KNOWLEDGE EVALUATION WITH A SEMANTIC WIKI WikiDesign Davy Monticolo1, Samuel Gomes2, Vincent Hilaire1 and Abder Koukam1 1SeT Laboratory, University of Technology UTBM, 90010 Belfort, France 2M3M Laboratory, University of Technology UTBM, 90010 Belfort, France Keywords: Semantic Wiki, Ontology, Knowledge Creation, Knowledge Evaluation, Multi-Agent System. Abstract: We will present in this paper how to ensure a knowledge evaluation and evolution in a knowledge management system by using a Semantic Wiki approach. We describe a Semantic Wiki called WikiDesign which is a component of a Knowledge Management system. Currently WikiDesign is use in engineering department of companies to emphasize technical knowledge. In this paper, we will explain how WikiDesign ensures the reliability of the knowledge base thanks to a knowledge evaluation process. After explaining the interest of the use of semantic wikis in knowledge management approach we describe the architecture of WikiDesign with its semantic functionalities. At the end of the paper, we prove the effectiveness of WikiDesign with a knowledge evaluation example for an industrial project. 1 INTRODUCTION in the wiki; It manages the collaborative editing i.e. if A wiki is a web site allows collaborative distant someone create a article, everybody can extend creation of information and editing of hypertext this article; content. Leuf (Leuf, 2001) was the first to propose a It proposes a strong linking, all the pages of the web site where people could create, modify, wiki are linked with each other using hyperlinks; transform and link pages all from within their browser and in a very simple way. Indeed Wikis be- It has a search function over the content of all come popular tools for collaboration on the web, and pages stored; many active online communities employ wikis to It allows the uploading of different content like exchange information. -

Enhancing the Development Process with Wikified Widgets Gary Gotchel Regis University

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Fall 2008 Enhancing the Development Process with Wikified Widgets Gary Gotchel Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gotchel, Gary, "Enhancing the Development Process with Wikified Widgets" (2008). All Regis University Theses. 146. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/146 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University College for Professional Studies Graduate Programs Final Project/Thesis Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. -

Knowledge Management Toolkit

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT TOOLKIT This Knowledge Management Toolkit has been created by the SDC Knowledge and Learning Processes Division in cooperation with Agridea Lindau. This toolkit is available in English only. Short versions in the form of a Vademecum are available in English, German, French, and Spanish. All texts are also available on the Internet www.daretoshare.ch For further information, please contact one of the members of the Department Knowledge and Learning Processes, [email protected] Published by Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) Federal of Foreign Affairs (FFA) www.deza.admin.ch Available from SDC Knowledge and Learning Processes Division Freiburgstrasse 130 CH-3003 Berne E-mail: [email protected] Tel. +4131 322 35 79 Fax +4131 324 13 47 Editors SDC, Knowledge and Learning Processes Division, 3003 Bern Ernst Bolliger, Agridea, 8315 Lindau Layout Annemarie Weishaupt, Nicole Moser (Cover) AGRIDEA, 8315 Lindau Photos Karina Muench, 8000 Zurich Copyright SDC 2009 ❑ We know that well proven ❑ methods and knowledge are With many other organisa- ➜ We want to available tions, we are connected and sum up the ➜ As publisher maintain a constructive and ❑ results and the We do have a lot of freedom of the present trusting relationship in organising our work experience of toolkit, the ❑ Reviews, evaluations and our activities, ❑ Only rarely (if ever) do we Knowledge studies help us to under- and to present ask our colleagues about and Learn- stand our activities and their them in a form their experience ing Processes -

Intranet Wikis

Intranet wikis Michel Buffa Mainline Group, I3S Laboratory, University of Nice currently visiting scientist with the Acacia Group, INRIA Sophia-Antipolis France 33 4 92 38 50 15 [email protected] ABSTRACT Very few academic papers addressed the intranet-wiki topic [4]. Historically, when business organizations realized that web In this paper we will first try to define the goals of a business technology could also be used internally, the development of organization intranet and see how the web technology and tools intra-webs took off rapidly. In 2002, several studies showed that helped or failed to reach these goals. 75% of web servers where running behind enterprise firewalls. Then we will present the wiki concept and try to understand why For years, the World Wide Web has been a de facto read only it has been such a phenomenon in the World Wide Web. We will media where anyone could browse and only a very few could show that its success relies on several social conditions that can publish. Similarly for intra-webs: the one webmaster syndrome not always been found in the business organization’s culture. killed in the egg the potential for collaboration and sharing. Finally, even when wikis have been adopted they are not a zero On the World Wide Web things have changed rapidly in the last defect solution to the knowledge sharing and collaboration two years with the emergence of Blogs and Wikis: the Web problem. They fill a gap but they may be improved. We will started to turn into a more writable media. -

Integrating External Sources in a Corporate Semantic Web Managed by a Multi-Agent System

From: AAAI Technical Report SS-03-01. Compilation copyright © 2003, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved. Integrating external sources in a corporate semantic web managed by a multi-agent system Tuan-Dung Cao, Fabien Gandon INRIA, ACACIA Team 2004, route des Lucioles, B.P. 93, 06902 Sophia Antipolis, FRANCE {Tuan-Dung.Cao | Fabien.Gandon}@sophia.inria.fr Abstract the adaptation of interactions to the user’s preferences, We first describe a multi-agent system managing a learning interest to build communities and collaborative corporate memory in the form of a corporate semantic web. filtering inside an organization. KnowWeb [Dzbor et al., We then focus on a newly introduced society of agents in 2000] relies on mobile agents to support dynamically charge of wrapping external HTML documents that are changing networked environment and exploits a domain relevant to the activities of the organization, by extracting model to extract concepts describing documents and use semantic Web annotations using tailored XSLT templates. them to answer queries. RICA [Aguirre et al., 2000] maintains a shared taxonomy in which nodes are attached to documents and uses it to push suggestions to interface Agents and corporate semantic webs agents according to user profiles. FRODO [Van Elst and Organizations are entities living in a world with a past, a Abecker, 2002] is dedicated to building and maintaining culture and inhabited by other actors; the pool of distributed organizational memories with an emphasis on knowledge they mobilize for their activities is not bounded the management of domain ontologies. Finally, our team neither by their walls nor by their organizational structures: participated to the European project CoMMA [CoMMA, organizational memories may include or refer to resources 2000], which aimed at implementing and testing a external to the company (catalogs of norms, stock-markets corporate memory management framework based on agent quotations, digital libraries, etc.). -

A Semantic Wiki to Support the Ideas Development and Knowledge Sharing in Innovation Activities

Wiki-I: A Semantic Wiki to Support the Ideas Development and Knowledge Sharing in Innovation Activities Knowledge is what places someone in the position to The Knowledge Persistent Layer is based on the Idea perform a particular task by selecting, interpreting and ontology proposed by Riedl [26] about the innovation domain evaluation information de-pending on the context [22] ,[31]. which defines a vocabulary and a semantic of the knowledge However a serious obstacle for the development of used in innovation ideas. The ontology is developed in Semantic Web applications is the lack of formal ontologies OWL-DL. This language is based on Description Logics and knowledge. Indeed, one of the main reasons of this is the (hence the suffix DL). Description Logics are a decidable rather high technical barrier for using Semantic Web fragment of First Order Logic and are therefore amenable to technologies that deters many domain experts from automated reasoning. It is therefore possible to automatically formalizing their knowledge. compute the classification hierarchy and check for In another hand, wiki systems are becoming more and inconsistencies in an ontology that conforms to OWL-DL. more popular as tools for content and information Consequently, the Idea ontology provides an integrated management. Much information is nowadays available in conceptual model for sharing information related to an systems like Wikipedia. Unfortunately, this vast information innovative idea. is not accessible for machines. If a small amount of this The Knowledge Persistent Layer is also composed by a information would be formalized to become knowledge, Query Processor which allows formulating queries to exploit wiki systems could provide improved interfaces and the knowledge based according to the structure of the advanced searching and navigation facilities. -

The Practice of Social Intranets

Report no: 7 April 2012 The practices of the social intranets Usage, benefits and sucess factors Lena Lundgren, Kicki Strandh & Catrin Johansson The Practice of Social Intranets Usage, Benefits and Success Factors Lena Lundgren, Kicki Strandh and Catrin Johansson Mid Sweden University 2012 2⏐ DEMICOM • CORE Authors: Lena Lundgren, Kicki Strandh & Catrin Johansson, Title: The practices of the social intranets – Usage, benefits and success factors Published by: DEMICOM, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, 2012 Editors: Catrin Johansson, Lars Nord & Ingela Wadbring Report series no. 7 ISBN 978-91-86694-86-9 The Practice of Social Intranets ⏐ 3 CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 Social media theories ..................................................................................................... 9 Social media, Web 2.0 and User Generated Content .................................... 9 Definitions of social media .............................................................................. 10 Intranets, Enterprise 2.0 and social intranets ................................................ 10 Definition of social intranet ............................................................................. 11 The users ............................................................................................................ -

Knowledge Management Toolkit

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT TOOLKIT This Knowledge Management Toolkit has been created by the SDC Knowledge and Learning Processes Division in cooperation with Agridea Lindau. This toolkit is available in English only. Short versions in the form of a Vademecum are available in English, German, French, and Spanish. All texts are also available on the Internet www-sdc.learningandnetworking.ch For further information, please contact one of the members of the Department Knowledge and Learning Processes, [email protected] Published by: Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) Federal of Foreign Affairs (FFA) www.deza.admin.ch Available from: SDC Knowledge and Learning Processes Division Freiburgstrasse 130 CH-3003 Berne E-mail: [email protected] Tel. +4131 322 35 79 Fax +4131 324 13 47 Editors: SDC, Knowledge and Learning Processes Division, 3003 Bern Ernst Bolliger, Agridea, 8315 Lindau Layout: Annemarie Weishaupt, Nicole Moser, Rita Konrad AGRIDEA, 8315 Lindau Photos: Karina Muench, Nicolas Merky Copyright: SDC 2009 Second Edition 2013 qq We know that well proven qq With many other organiza- H We want to methods and knowledge are tions, we are connected and sum up the available H As publisher maintain a constructive and results and the qq We do have a lot of freedom of the present trusting relationship experience of in organising our work toolkit, the qq Reviews, evaluations and our activities, qq Only rarely (if ever) do we Knowledge studies help us to under- and to present ask our colleagues about and Learn- stand our activities and -

Knowledge Management in Medium-Sized Software Consulting Companies

Knowledge Management in Medium-Sized Software Consulting Companies An investigation of Intranet-based Knowledge Management Tools for Knowledge Cartography and Knowledge Reposito- ries for Learning Software Organisations Torgeir Dingsøyr Knowledge Management in Medium-Sized Software Consulting Companies An Investigation of Intranet-based Knowledge Management Tools for Knowledge Cartography and Knowledge Repositories for Learning Software Organisations Submitted for the Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doktor Ingeniør Department of Computer and Information Science Faculty of Information Technology, Mathematics and Electrical Engineering Norwegian University of Science and Technology January, 2002 ©Unipub forlag and Torgeir Dingsøyr 2002 ISBN 82-7477-107-9 ISSN: 1502-1408 Information concerning this publication can be directed to: Phone: +47 22 85 30 30 Fax: +47 22 85 30 39 E-mail: [email protected] The book can also be purchased at www.gnist.no Cover: Askim Grafix AS Printed in Norway by: GCSM AS, Oslo 2002 Layout: Hanne Holmesland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without permission. Unipub forlag is a subsidiary company of Akademika AS, owned by Studentsamskipnaden i Oslo Abstract Companies that develop software have a pressure from customers to deliver better solutions, and to deliver solutions faster and cheaper. Many researchers have worked with suggestions on how to improve the devel- opment process; software process improvement. As software develop- ment is a very knowledge intensive task, both researchers and industry have recently turned their attention to knowledge management as a means to improve software development. This often involves developing technical tools, which many companies have spent resources on. -

Sweetwiki : Semantic Web Enabled Technologies in Wiki

SweetWiki : Semantic WEb Enabled Technologies in Wiki Michel Buffa 1,2 , Gaël Crova 3, Fabien Gandon 2, Claire Lecompte 3, Jeremy Passeron 3 1 Mainline Group, I3S Laboratory, University of Nice [email protected] 2 Acacia Group, INRIA Sophia-Antipolis, France [email protected] 3 University of Nice, France Abstract. Wikis are social web sites enabling a potentially large number of par- ticipants to modify any page or create a new page using their web browser. As they grow, wikis suffer from a number of problems (anarchical structure, large number of pages, aging navigation paths, etc.). We believe that semantic wikis can improve navigation and search. In SweetWiki we investigate the use of se- mantic web technologies to support and ease the lifecycle of the wiki. The very model of wikis was declaratively described: an OWL schema captures concepts such as WikiWord, wiki page, forward and backward link, author, etc. This on- tology is then exploited by an embedded semantic search engine (Corese). In addition, SweetWiki integrates a standard WYSIWYG editor (Kupu) that we extended to support semantic annotation following the "social tagging" ap- proach made popular by web sites such as flickr.com. When editing a page, the user can freely enter some keywords in an AJAX-powered textfield and an auto-completion mechanism proposes existing keywords by issuing SPARQL queries to identify existing concepts with compatible labels. Thus tagging is both easy (keyword-like) and motivating (real time display of the number of re- lated pages) and concepts are collected as in folksonomies. To maintain and re- engineer the folksonomy, we reused a web-based editor available in the under- lying semantic web server to edit semantic web ontologies and annotations.