An Ode to the Zen Master: Phil Jackson's Spiritual Rhetoric As An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Cartwright

Bill Cartwright Bill Cartwright is a winner! He was in his basketball career, he is in his business career and he continues to be a winner in his family life. Cartwright was a 7’1” NBA center was a dominant physical presence for 3 teams. He was drafted in the 1st round of the 1979 NBA draft, #3 overall, by the New York Knicks. He made an All-Star Game appearance in his rookie season and was named to the All Rookie First Team. He was named team captain of the Knicks but 4 separate fractures to his foot began to slow him steps. Bill was traded to the Chicago Bulls in 1988 and it was here that he fully established himself as a presence. He was once again named team captain and led the Bulls to 3 consecutive NBA championships in 1991, 1992, and 1993. In 1994, he moved on as a free agent to the Seattle SuperSonics where he spent the final season of his 16 year playing career. In 1996, Bill rejoined the Chicago Bulls as an assistant coach and won two more NBA championships with the team in 1997 and 1998. In 2001, he took over the Bulls’ head coach where he remained until 2003, coaching a team that had been stripped of its best players. He moved on from Chicago to be an assistant coach with the New Jersey Nets and Phoenix Suns before spending the 2013 season coaching in Japan and 2014 as head coach of the Mexican National Team. Cartwright has firmly established himself in the business world as the owner of a car dealership and a restaurant and he recently divested himself from a successful security services firm. -

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

Getting Data with R

Getting Data with R Tony Yao-Jen Kuo How to get data with R I From web Overview I From files Overview I From files I From web Getting data from files Using read.csv() for CSV files I CSV stands for comma separated values file_url <- "https://storage.googleapis.com/ds_data_import/chicago_bulls_1995_1996.csv" df <- read.csv(file_url, stringsAsFactors = FALSE) # personal preference... dim(df) ## [1] 15 7 Using read.table() for general tabular text files file_url <- "https://storage.googleapis.com/ds_data_import/chicago_bulls_1995_1996.txt" df <- read.table(file_url, header = TRUE, sep = ";") ## Warning in scan(file = file, what = what, sep = sep, quote = quote, dec = ## dec, : EOF within quoted string dim(df) ## [1] 15 7 Using readxl package for Excel spreadsheets install.packages("readxl") library(readxl) file_path <- "/Users/kuoyaojen/Downloads/fav_nba_teams.xlsx" chicago_bulls <- read_excel(file_path) head(chicago_bulls) ## # A tibble: 6 x 7 ## No. Player Pos Ht Wt `Birth Date` College ## <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> ## 1 0 Randy Brown PG 6-2 190 May 22, 1968 University of H~ ## 2 30 Jud Buechler SF 6-6 220 June 19, 1968 University of A~ ## 3 35 Jason Caffey PF 6-8 255 June 12, 1973 University of A~ ## 4 53 James Edwards C 7-0 225 November 22, 1955 University of W~ ## 5 54 Jack Haley C 6-10 240 January 27, 1964 University of C~ ## 6 9 Ron Harper PG 6-6 185 January 20, 1964 Miami University Importing other sheets boston_celtics <- read_excel(file_path, sheet = "boston_celtics_2007_2008") head(boston_celtics) Reading specific cell -

June 24, 1996 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep June 1996 6-24-1996 Daily Eastern News: June 24, 1996 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1996_jun Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: June 24, 1996" (1996). June. 4. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1996_jun/4 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1996 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in June by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STORMS a high Hoops near 87 The assistant INSIDE Daily Eastern leaves, too Time to Kevin Mouton Eastern Illinois University accepts job at MONDAY Charleston, Ill. 61920 June 24, 1996 New relax Vol. 81, No. 155 Counseling center gives advice 8 pages Hampshire on relaxation techniques. News PAGE PAGE 5 “Tell the truth and don’t be afraid” 8 McBee resigns ilar situation Athletic director arose in 1993 when McBee’s leaves post after predecessor, Mike Ryan, left two years at helm the university to By MATT ERICKSON pursue other in- Managing editor terests. This time, an Bob McBee After an often-criticized two- acting director year stretch at the helm of East- of athletics will not be named in ern’s athletic department, Bob the same fashion as one was prev- McBee resigned the post of dir- iously. Upon Ryan’s resignation, ector of athletics on Thursday. John Craft McBee, however, will not be was named leaving the university just yet. acting ath- ■ Athletic depart- In a joint decision by McBee letics dir- ment looks to fill ector. -

The Inside Story of One Turbulent Season with Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls Pour Chaque Appareil

Pour Kindle The Jordan Rules: The Inside Story of One Turbulent Season with Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls Sam Smith’s seminal, New York Times bestselling “eye-opener” (The San Diego Union-Tribune) on Michael Jordan and the 1990-1991 Chicago Bulls team—perfect for fans of ESPN’s hit documentary series The Last Dance. This is the book that changed the way the world viewed Michael Jordan, while delivering nonstop excitement, tension, and thrills. The Jordan Rules chronicles the season that changed everything for Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. After losing in the playoffs to the “Bad Boys” Detroit Pistons for three consecutive years, the Bulls finally broke through and swept the Pistons in the 1991 Eastern Conference Finals, on the way to their first NBA championship. Celebrated sportswriter Sam Smith was there for the entire ride. He reveals a candid and provocative picture of Michael Jordan during the season in which his legacy began to be defined, and seeks to figure out what drove him. The Jordan Rules covers everything from his stormy relationships with his coaches and teammates and power struggles with management—including verbal attacks on general manager Jerry Krause and tantrums against coach Phil Jackson—to Jordan’s obsessions with becoming the leading scorer, and his refusal to pass the ball in the crucial minutes of big games. Jordan’s teammates also tell their side of the story, from Scottie Pippen, to Horace Grant, to Bill Cartwright. And Phil Jackson—the former flower child who blossomed into one of the NBA’s top motivators and finally found a way to coax Jordan and the Bulls to their first title—is studied up close. -

2007-08 MBB Section 1.Indd

The Galen Center Home of USC Basketball 2007-2008 • 1 • USC BASKETBALL Table of Contents The 2007-2008 Trojans Trojan Quick Facts/Table of Contents ......................2 2007-2008 Schedule ................................................3 TROJAN QUICK FACTS Galen Center Facts ...............................................4-7 Galen Center Records ...........................................8-9 This is USC Hoops ............................................10-21 Location ......................................................................................................... Los Angeles, Calif. 2007-2008 Season Outlook ............................ 22-24 Founded ................................................................................................................................ 1880 Head Coach Tim Floyd ................................... 25-29 Enrollment ................................................................................. 33,000 (16,500 undergraduates) Assistant Coach Gib Arnold ................................. 30 President ................................................................................................... Dr. Steven B. Sample Assistant Coach Bob Cantu................................. 31 Colors ................................................................................................................. Cardinal & Gold Strength & Conditioning Manager Rudy Hackett . 32 Nickname.......................................................................................................................... -

Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

SOT¯ O¯ ZEN An Introduction to Zazen SOT¯ O¯ ZEN: An Introduction to Zazen Edited by: S¯ot¯o Zen Buddhism International Center Published by: SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO 2-5-2, Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8544, Japan Tel: +81-3-3454-5411 Fax: +81-3-3454-5423 URL: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/ First printing: 2002 NinthFifteenth printing: printing: 20122017 © 2002 by SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan Contents Part I. Practice of Zazen....................................................7 1. A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the Practice of the Bodhisattva Way 9 2. How to Do Zazen 25 3. Manners in the Zend¯o 36 Part II. An Introduction to S¯ot¯o Zen .............................47 1. History and Teachings of S¯ot¯o Zen 49 2. Texts on Zazen 69 Fukan Zazengi 69 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Bend¯owa 72 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Zuimonki 81 Zazen Y¯ojinki 87 J¯uniji-h¯ogo 93 Appendixes.......................................................................99 Takkesa ge (Robe Verse) 101 Kaiky¯o ge (Sutra-Opening Verse) 101 Shigu seigan mon (Four Vows) 101 Hannya shingy¯o (Heart Sutra) 101 Fuek¯o (Universal Transference of Merit) 102 Part I Practice of Zazen A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the 1 Practice of the Bodhisattva Way Shohaku Okumura A Personal Reflection on Zazen Practice in Modern Times Problems we are facing The 20th century was scarred by two World Wars, a Cold War between powerful nations, and countless regional conflicts of great violence. Millions were killed, and millions more displaced from their homes. All the developed nations were involved in these wars and conflicts. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs

2013-14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs 60 Atlanta Hawks 10 Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs Gold 60 Atlanta Hawks 5 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs 88 Atlanta Hawks 325 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs Gold 88 Atlanta Hawks 25 Dennis Schroder Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 23 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys 25 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys Prime 25 Atlanta Hawks 25 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs 4 Atlanta Hawks 15 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs Prime 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink 56 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink Gold 56 Atlanta Hawks 5 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs 1 Atlanta Hawks 35 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 1 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs 4 Atlanta Hawks 25 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs Gold 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs 10 Atlanta Hawks 15 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs Prime 10 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink 23 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink Gold 23 Atlanta Hawks 5 Pero Antic Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 43 Atlanta Hawks 299 Spud Webb Main Exhibit Signatures 2 Atlanta Hawks 75 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs 3 Atlanta Hawks 199 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 3 Atlanta Hawks 25 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs 31 Atlanta Hawks 325 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs Gold 31 Atlanta Hawks 25 groupbreakchecklists.com 13/14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Bill Sharman Top-Notch Autographs -

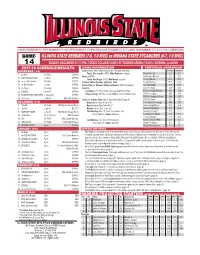

ILLINOIS STATE REDBIRDS (7-6, 1-0 MVC) Vs INDIANA STATE SYCAMORES (6-7, 1-0 MVC) 14 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 31 // 3 P.M

6 NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES // 13 NIT APPEARANCES // 5 MVC REGULAR SEASON TITLES // 4 MVC TOURNAMENT TITLES // 21 ALL-AMERICANS GAME: ILLINOIS STATE REDBIRDS (7-6, 1-0 MVC) vs INDIANA STATE SYCAMORES (6-7, 1-0 MVC) 14 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 31 // 3 P.M. // DOUG COLLINS COURT AT REDBIRD ARENA (10,200) // NORMAL, ILLINOIS 2017-18 SCHEDULE/RESULTS GAME INFORMATION STATISTICAL COMPARISON NOVEMBER (3-4) Listen: Illinois State Radio Network (93.7 FM and 1230 AM) IllState IndState Overall Record 7-6 6-7 5 LEWIS 1 W, 79-52 ESPN3 Talent: Dick Luedke (PBP), Mike Matthews (analyst) Watch: ESPN3 Conference Record 1-0 1-0 11 at Florida Gulf Coast L, 87-98 ESPN3 Talent: Kurt Pegler (PBP), Bob Morris (analyst) Scoring Offense 74.5 74.8 2 16 vs. South Carolina W, 69-65 ESPN2 In-Game Twitter Updates: @Redbird_MBB Scoring Defense 75.5 73.8 17 vs. Boise State 2 L, 64-82 ESPN2 Illinois State vs. Missouri Valley Conference: 394-315 (page 9) Scoring Margin -0.9 +0.9 19 vs. Tulsa 2 W, 84-68 ESPNU Coaches: FG Percentage .430 .427 22 QUINCY W, 86-57 ESPN3 Dan Muller (111-71) is in his sixth season at Illinois State. FG Percentage Defense .434 .434 3FG Percentage .363 .395 25 CHARLESTON SOUTHERN L, 62-64 (ot) ESPN3 Greg Lansing (126-115) is in his eighth season at Indiana State 3FG Percentage Defense .304 .330 29 at Nevada 3 L, 68-98 MWN On Stadium Series vs. Indiana State: Illinois State leads 63-55 (page 8) 3FG Per Game 9.8 9.3 DECEMBER (4-2) Home: Illinois State leads 39-15 Free Throw Percentage .684 .701 2 TULSA W, 65-58 NBC Sports Chicago Plus+ Road: Indiana State leads 37-21 Rebounding Offense 33.4 36.5 6 at BYU L, 68-80 BYU TV Neutral: Illinois State leads 3-2 Rebounding Margin -7.7 +0.4 9 MURRAY STATE L, 72-78 NBC Sports Chicago Plus+ First Meeting: Jan. -

An Aristotelian Interpretation of Bojo Jinul and an Enhanced Moral Grounding

religions Article An Aristotelian Interpretation of Bojo Jinul and an Enhanced Moral Grounding Song-Chong Lee Religious Studies and Philosophy, University of Findlay, Findlay, OH 45840, USA; lee@findlay.edu Received: 17 March 2020; Accepted: 13 April 2020; Published: 16 April 2020 Abstract: This paper explores the eclecticism of Bojo Jinul (1158–1210 CE), who is arguably the most influential historic figure in establishing and developing the Buddhist monastic institution of Korea. As a great harmonizer of the conflicting Buddhist trends in the late Goryeo period, Jinul not only shaped the foundation of the traditional monastic discipline balanced between theory and practice but also made Korean Buddhist thoughts known to a larger part of East Asia. I revisit the eclecticism of Bojo Jinul on harmonizing the two conflicting understandings of enlightenment represented by Seon (Cha’n) and Gyo (Hwaeom study) schools: the former stressing sudden enlightenment by sitting mediation and oral transmission of dharma and the latter stressing gradual cultivation by the formal training of textual and doctrinal understanding specifically on the Hwaeom Sutra. Utilizing the metaphysics of Aristotle, I confirm the logical validity of his eclecticism and address some of its moral implications. Keywords: Korean Buddhism; Jinul; sudden enlightenment; gradual cultivation; Korean Seon; Zen; potentiality and actuality; Aristotelian metaphysics 1. Introduction This paper explores the eclecticism of Bojo Jinul (1158–1210 CE), who is arguably the most influential historic figure in establishing and developing the Buddhist monastic institution of Korea. As a great harmonizer of the conflicting Buddhist trends in the late Goryeo period,1 Jinul not only shaped the foundation of the traditional monastic discipline balanced between theory and practice2 but also made Korean Buddhist thoughts known to a larger part of East Asia. -

Meet the Ucla Bruins

MMEETEET TTHEHE UUCLACLA BBRUINSRUINS MMEETEET TTHEHE UUCLACLA BBRUINSRUINS 2010-11 Jerime Anderson had surgery on July 1, 2010 JJERIMEERIME to repair a nasal fracture that he sustained in AANDERSONNDERSON a pick-up game during the summer. 2009-10 ##55 • JJUNIORUNIOR • GGUARDUARD • 66-2-2 • 118383 Anderson played in 29 games in 2009-10, AANAHEIM,NAHEIM, CCAA ((CANYONCANYON HHS)S) averaging 24.4 minutes per contest while making 14 starts at the point … he scored in all but three of the 29 games he played in, reaching double fi gures seven times, including a career-high 15 points in 26 minutes in a loss to California (Mar. 12) in the semifi nals of the Pac-10 Tournament … recorded an assist in 27 of the games he played, including a career-high seven assists to go with 12 points, four rebounds, one block and one steal in a win over Colorado State (Dec. 22) … averaged 5.8 points, 1.9 rebounds and 1.0 steals per game … fi nished second on the team in assists (100, 3.5 apg), which ranked seventh in the Pac-10 … was also second on the team in assist to turnover ratio at 1.56 (100 AST, 64 TO), which ranked fourth in the Pac-10 … scored 13 points and added a career-high-tying seven assists and one steal in a win over New Mexico State (Dec. 15) … tallied 11 points, four rebounds and two assists in the overtime win at California (Jan. 6) … registered four points, three rebounds, six assists and a career-high six steals in the win over Delaware State (Dec.