David Roberts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formal Meeting Minutes

CYNGOR CYMUNED GORSLAS COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minutes of the meeting of the Gorslas Community Council held at Ysgol Cefneithin C.P. School on Monday, 11th July, 2016, at 7.00.p.m. 48.0. Item 1: Record of those Present/Apologies Members Present: Cllrs: Wyn Edwards (Chair), Clive Green, Darren Price, Janice Price, Huw Davies, Nia Lewis, Simon Martin, Terry Jones, Brian Kirby, and Aled Owen. Cllr T Davies joined the meeting at 7.50p.m. Others: Llew Thomas Clerk to the Council and Mr Hefin Jones, Translator. Apologies for absence: Cllrs Ellis Davies, Tina Jukes 48.1. Welcome The Chair welcomed everyone to the meeting and thanked them for their attendance. Members were sorry to learn that Cllr Tina Jukes had suffered a family bereavement and wished to extend their sympathy to her and her Family. It was resolved unanimously that a letter of sympathy be sent by the Clerk to Cllr Jukes. 49.0. Item 2 Declaration of Interest. No declarations of interest were made at this point When discussing Item 10 a declaration of interest was made by Cllr T Davies. 50.0. Item 3 Consider the Minutes of the Meeting held on the 13th June, 2016. Under the direction of the Chair members proceeded to examine and consider each page of the minutes of the meeting for accuracy. Resolved: Proposed by Cllr J Price and seconded by Cllr C. Green and agreed by all present that the minutes were a true and accurate record of proceedings and decisions. 51.0. Item 4 Park and General Matters 51.1. -

PD July 2006 Master

Pobl Dewi Menter Esgobaeth Tyddewi . An initiative of the Diocese of St David Gorffenaf / July 2006 N o w i s t h e NowNowNow isisis thethethe TTTimeimeime forforfor ActionActionAction Bishop’s Call to Venturing Parishes by John Holdsworth S Mission Action Plans were presented to three special services, ABishop Carl Cooper told delegates that the time for talking was over. “The Church is great at bureaucracy,” he said, “but now is the time for action.” He stressed again the importance of the key elements of the Venturing in Mission direction, and defended planning as a Christian enterprise. Drawing a parallel from his experience as a member of the Broadcasting Council for Wales, he said that we must have ways of judging success. Broadcasters judge programmes by their quality, the number of people who are attracted to them, and by their ability to make a difference. The Church has something to learn from this. Around 700 people attended branches. Delegates at the St the three services, on behalf of all David’s service in Tenby placed the parishes in the diocese. Each a stone to add to a cairn. This was service was locally devised, and meant to speak not only of the each drew on different symbols to sense of place and the living interpret the significance of the stones Bible image, but also of the occasion. The Cardigan service, idea that travellers add to a cairn held in Lampeter, concentrated as they pass through: their small on the theme of light. The contribution adding to something Carmarthen archdeaconry service that future generations will find held in Carmarthen town used the a beacon and landmark, Bishop Carl said “there is something deeply humbling about receiving plans with the words, we are Biblical image of the vine and the explained the archdeacon. -

Mynyddcerrig, Llanelli, SA15 5BL LIVING ROOM 23'10" X 13'11" (7.27M X 4.25M) CLOAKROOM 5'4" X 4'10" (1.65M X 1.49M) Low Level W.C

Tanygraig Mynyddcerrig, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA15 5BL Guide price £400,000 A Choice smallholding of 10 acres or thereabouts set in scenic location a short distance from village commanding fine views over its own traditional courtyard and land towards the Black Mountain The property comprises PERIOD STONE FARMHOUSE with many ORIGINAL features together with fine adjoining stone range with conversion potential and additional stone built former Cowshed with ancillary buildings. The accommodation provides: Reception Hall, Kitchen/Breakfast Room; Sitting/Dining Room with Rayburn range and open fireplace; Cloakroom; Conservatory style porch; 3 Bedrooms; Bathroom. Oil fired central heating; Double Glazing. Adjoining stone range with Inglenook fireplace and mezzanine. Sweeping drive to courtyard with versatile range buildings. Productive pasture paddocks and attractive Oak woodland. To auction at an early date unless previously sold. Idyllic - book a viewing today Mynyddcerrig, Llanelli, SA15 5BL LIVING ROOM 23'10" x 13'11" (7.27m x 4.25m) CLOAKROOM 5'4" x 4'10" (1.65m x 1.49m) Low level W.C. Hand basin on vanity with mixer tap. Ceramic tiled floor. Radiator. REAR CONSERVATORY PORCH 10'5" x 4'4" (3.18m x 1.34m) Rayburn solid fuel range in deep tiled recess. Open fireplace. Exposed ceiling beams. Stairs to first floor. 2 Radiators. ANOTHER ROOM ASPECT French doors to front and rear. Quarry tiled floor. Radiator. FIRST FLOOR LANDING Built in Airing Cupboard with linen shelves and radiator. BEDROOM 14'0" x 10'11" (4.27m x 3.34m) Pointed stone wall. Access to attic via pull down ladder. Radiator. BEDROOM 12'10" x 11'1" (3.92m x 3.39m) KITCHEN/BREAKFAST ROOM 18'11" x 5'2" (5.78m x 1.58m) Wall lights. -

Deposit - Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 – 2033

Deposit - Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 – 2033 Draft for Reporting Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Foreword To be inserted Deposit Draft – Version for Reporting i Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Contents: Page No: Policy Index iii How to View and Comment on the Deposit Revised LDP vi 1. Introduction 1 2. What is the Deposit Plan? 3 3. Influences on the Plan 7 4. Carmarthenshire - Strategic Context 12 5. Issues Identification 25 6. A Vision for ‘One Carmarthenshire’ 28 7. Strategic Objectives 30 8. Strategic Growth and Spatial Options 36 9. A New Strategy 50 10. The Clusters 62 11. Policies 69 12. Monitoring and Implementation 237 13. Glossary 253 Appendices: Appendix 1: Context – Legislative and National Planning Policy Guidance Appendix 2: Regional and Local Strategic Context Appendix 3: Supplementary Planning Guidance Appendix 4: Minerals Sites Appendix 5: Active Travel Routes Appendix 6: Policy Assessment Appendix 7: Housing Trajectory Appendix 8: Waste Management Facilities Deposit Draft – Version for Reporting ii Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Policy Index Page No. Strategic Policy – SP1: Strategic Growth 70 • SG1: Regeneration and Mixed Use Sites 72 • SG2: Reserve Sites 73 • SG3: Pembrey Peninsula 75 Strategic Policy – SP2: Retail and Town Centres 76 • RTC1: Carmarthen Town Centre 82 • RTC2: Protection of Local Shops and Facilities 84 • RTC3: Retail in Rural Areas 85 Strategic Policy – SP3: A Sustainable Approach to Providing New -

Tafod Twrog Rhif/No 78 August/Awst September/Medi October/Hydref 2019

Tafod Twrog Rhif/No 78 August/Awst September/Medi October/Hydref 2019 Ficer/Vicar Canon D Roberts (from 3 September 2019) 01267 275504 Darllenydd Lleyg / Lay Reader Mrs Jean Voyle Williams M.B.E., B.Ed. 01267 275222 www.eglwysllanddarog.org / www.llanddarogchurch.org Dear Friends I look forward to being in your midst as I begin a new chapter of my ministry with you in September. My spouse Debbie is from the Isle of Wight and we have been married for over thirty years. Debbie is a faithful member of the ‘Mothers Union’ and will be attending the General Conference in Portsmouth this year. Our two sons live and work in Bristol and our daughter lives with us and has recently been working with people with special needs. I was born in Llanddewi Brefi and began my ministry at the age of 23. I spent part of my ministry in the diocese of Bangor where I was ordained, but for the past seventeen years have ministered in this diocese, in the parish of Newcastle Emlyn. As a couple we enjoy the countryside and look forward to living near the Botanic Gardens. In my experience, walking amidst the natural melodies of the countryside and its sweet aromas is a great help to unwind and to reflective meditation; as is listening to classical music. I derive special inspiration from listening to the religious and classical music of Arvo Pärt. Last year I had the privilege of being ‘Director of Ordinands’ for the diocese. Undertaking this role has opened up a new perspective for me on ministry within the diocese and it is inspiring to be involved in supporting and encouraging new candidates for ministry. -

Deposit-Ldp-Combined-En.Pdf

Deposit Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Foreword The LDP identifies the level and distribution of growth and development needed in accordance with the diverse character of our As Executive Board Member whose remit is Strategic Planning, I am County’s communities. The LDP also contains a range of policies pleased to present the deposit documents for the Revised and land use allocations, including provision for new homes and Carmarthenshire County Council Local Development Plan (LDP) employment across Carmarthenshire up to 2033. which were approved for public consultation at the meeting of the County Council on the 13th November 2019. My thoughts now turn to the formal consultation on the deposit LDP and I would encourage as many of you as possible to submit your Since the Council resolved to commence work on a Revised LDP in comments. All duly made comments will be reported back to a January 2019, we have been listening to the views of a wide range meeting of the full County Council. It is important that we hear all of of stakeholders and partners. Whilst I remain confident that parts of your views if we are to achieve our goal of formulating a land use the Current / Adopted LDP are fit for purpose, I felt it was important plan that can assist in delivering our Vision for “One that the Council tried to gain an understanding of those elements of Carmarthenshire” - whether it be in urban or rural areas of our the Current / Adopted LDP that need to be looked at again as part of County. -

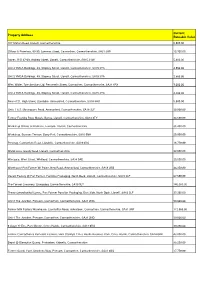

Empty NDR Properties @ 21 May 09

Current Property Address Rateable Value 107 Station Road, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire 5,500.00 Offices & Premises, 89-90, Lammas Street, Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, SA31 3AP 15,750.00 Stores, R/O 47-69, Andrew Street, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA15 3YW 5,400.00 Unit 4 YMCA Buildings, 49, Stepney Street, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA15 3YA 4,550.00 Unit 2 YMCA Buildings, 49, Stepney Street, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA15 3YA 2,800.00 West Wales Tyre Services Ltd, Pentrefelin Street, Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, SA31 1RX 7,000.00 Unit 3 YMCA Buildings, 49, Stepney Street, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA15 3YA 4,300.00 Rear of 21, High Street, Llandybie, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3HX 5,500.00 Units 1 & 5, Maesquarre Road, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 2LF 20,000.00 Former Foundry Rees Metals, Bynea, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA14 9TY 24,500.00 Workshop Offices & Premises, Furnace, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire 35,250.00 Workshop, Burrows Terrace, Burry Port, Carmarthenshire, SA16 0NH 20,000.00 Pencrug, Carmarthen Road, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, SA19 6RS 18,750.00 Warehouse, Sandy Road, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire 22,000.00 Westgate, West Street, Whitland, Carmarthenshire, SA34 0AE 20,500.00 Warehouse Part Former Wf Paine, New Road, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3BD 44,250.00 Vacant Factory @ Part Former, Pontrilas Packaging, North Dock, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA15 2LF 67,500.00 The Former Creamery, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire, SA19 9LY 146,000.00 Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru, Part Former Pontrilas Packaging, East Side, North Dock, -

Written-Statement-En.Pdf

Foreword Foreword As Executive Board Member for Regeneration and Leisure, I am pleased to present the Carmarthenshire County Council Local Development Plan (LDP) as adopted by the County Council on December 10 2014. Whilst taking account of national plans, policies and programmes, the Carmarthenshire LDP provides a locally distinctive means of shaping the future use of land within our County. As such, the Plan takes account of our County’s unique characteristics and qualities and it gives me pleasure to see the emphasis placed on sustainable development as a central principle. I am also pleased to note the close working relationship that the Plan demonstrates with the Integrated Community Strategy. In noting that the LDP is one of only two plans that the Authority is statutorily obliged to produce, I consider that this Plan provides a robust mechanism for delivering the Council’s ambitions over the coming years. I particularly welcome the Plan’s recognition of the importance of promoting a sustainable distribution of growth and regeneration within the context of approaches in regional working. The LDP considers a wide range of issues and presents a vision for the future of the County. The Plan’s Strategy will help realise this vision by identifying the level and distribution of growth and development needed in accordance with the diverse character of the County’s communities. The Plan will deliver its Strategy via the implementation of a range of policies and land use allocations, including provision for new homes and employment over the plan period. I also note that the Sustainability Appraisal (SA) and Habitats Regulations Assessment (HRA) have both provided important roles within the Plan making process and that all regulatory requirements have been adhered to. -

November 2020 Meeting of Llanddarog Community Council Held Online on the 11/11/2020 at 19.00

CYNGOR CYMUNED LLANDDAROG COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minutes of the November 2020 meeting of Llanddarog Community Council held online on the 11/11/2020 at 19.00. 136/2020-2021 Present: Councillors: M Rees (Chair), R Jones, J Youens, H Jones, W Evans, J Williams O.B.E, S Herridge, T Evans, E Davies, R Owen, R Newell. County Councillor A Davies. Clerk 137/2020-2021 Apologies. None. 138/2020-2021 Declarations of Personal Interest. None. 139/2020-2021 Opportunity for the Public to Address the Council on Agenda Items. None. 140/2020-2021 Policing and Road Safety Matters. Cllr J Williams expressed concern in the October meeting 121/2020-2021 that Crosshands Police Station was being closed and moved to Ammanford. Cllr R Jones enquired if notification had been received regarding the closure. The Clerk informed the members that no notification had been received. The Clerk contacted Dyfed Powys Police and a letter of response was received from Chief Constable Mark Collins QPM and forwarded to all members on 04/11/2020. The letter stated “I can confirm that there are no plans to close Cross Hands. That said we are in consultation with the local health board about co-locating within the new Cross Hands Health Centre”. The Clerk also informed the members that he had received a telephone call from Crosshands Police Station stating that more officers would be visible in the Crosshands area after 01/01/2021 and that they were still policing the issue of speeding vehicles in Porthyrhyd. Resolved to note. 141/2020-2021 County Council Matters - County Cllr A Davies. -

December 2020 Meeting of Llanddarog Community Council Held Online on the 09/12/2020 at 19.00

CYNGOR CYMUNED LLANDDAROG COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minutes of the December 2020 meeting of Llanddarog Community Council held online on the 09/12/2020 at 19.00. 156/2020-2021 Present: Councillors: M Rees (Chair), R Jones, J Youens, H Jones, W Evans, J Williams O.B.E, R Owen. County Councillor A Davies. Clerk 157/2020-2021 Apologies. Councillors: S Herridge, R Newell, E Davies 158/2020-2021 Declarations of Personal Interest. None. 159/2020-2021 Opportunity for the Public to Address the Council on Agenda Items. None. 160/2020-2021 Policing and Road Safety Matters. Cllr J Youens reported that residents from Mynyddcerrig had complained about the amount of gravel accumulating on the side of the road and the potential damage to vehicles since the resurfacing was done in September 2020. Resolved for Clerk to contact relevant department. Cllr W Evans joined the meeting at 19.06. Cllr M Rees reported that the road was subsiding in the centre and a number of culverts/drains were blocked between Rose Villa and Cwm Coch Farm in Cwmisfael. Resolved for Clerk to contact relevant department. 161/2020-2021 County Council Matters - County Cllr A Davies. County Cllr A Davies began her report by saying “First of all, may I thank everyone for all the support during 2020. May I wish you all a Merry and peaceful Christmas and a better year for 2021” Shelter Cymru has advertised that Carmarthenshire County Council has not built any social housing in 2019 and wanted to know why these are the figures that are being posted on the website. -

Role and Function Jan 2020 (6MB, Pdf)

1. Introduction 1.4 The above “audit” will allow the Paper to provide a wider “scene Purpose of this Paper setting” exercise in terms of role and function, and proceeds to frame a wider discussion as to the most appropriate method of classifying a 1.1 This paper is the second iteration of the Role and Function Paper settlement’s potential contribution within the revised LDP. which was first published as background evidence to the Pre-Deposit Preferred Strategy in December 2018. This paper seeks to elaborate on 1.5 In considering a settlement hierarchy for the revised LDP, this paper previous evidence and informs the considerations of spatial framework and considers the rationale of adopting a character area / cluster approach growth distribution. In this respect, this paper should be read in conjunction rather than what has traditionally been considered through a ‘top down’ with the Housing Distribution Paper approach based on key services and facilities. 1.2 The first part of this paper provides an overview of the background 1.6 A character area / cluster approach seeks to acknowledge evidence, including the LDP monitoring reports, and other Corporate or contrasting spatial features and the respective contributions of individual external strategies, which has allowed the Local Authority to understand settlements within these areas. Achieving a consensus in relation to such the role and function that settlements make within the county. Itidentifies matters would provide a strong foundation for engendering local ownership those settlements that are not delivering their intended levels of growth of the Plan which supports the development of the Preferred Strategy. -

The Council's Proposed Changes Recommended by the Inspector

Carmarthenshire LDP Inspector’s Report: Appendix A Appendix A: The Council’s proposed changes recommended by the Inspector – Written Statement, Addendum 1 and Addendum 2 Change Policy: Paragraph: Proposed Change: Ref No. MAC1 Revise Chapter 1: Introduction. See Appendix 1 of this schedule for the revisions to the Introduction. MAC2 2.3.1 & 2.3.2 Delete paragraph 2.3.1 and 2.3.2. South West Wales Regional Waste Plan First Review (Recommended Draft) – March 2008 2.3.1 The Regional Waste Plan (RWP) for South West Wales provides a land use planning framework for the management of all types of waste. In accordance with TAN 21: Waste, each of the three Regions in Wales (South West, South East and North) are required to produce a RWP, showing how that area will deal with its waste in the future. It is the responsibility of each constituent local planning authority to implement the framework through their LDP. MAC3 Insert the following paragraphs within section 2.3: Swansea Bay City Region The Swansea Bay City Region encompasses the Local Authority areas of Pembrokeshire, Carmarthenshire, City and County of Swansea and Neath Port Talbot. It brings together business, local government and a range of other partners, working towards creating economic prosperity for the people who live and work in our City Region. The Swansea Bay City Region Economic Regeneration Strategy 2013 – 2030 sets out the strategic framework for the region aimed at supporting the areas development over the coming decades. The LDP in recognising the role of Carmarthenshire makes provision through its policies and proposals for employment development with the economy an important component of the Plan’s strategy.