First Class Boys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J Class Fleet Destroyer

J CLASS FLEET DESTROYER FEATURE ARTICLE written by James Davies For KEY INFORMATION Country of Origin: Great Britain. Manufacturers: Hawthorn Leslie, John Brown, Denny, Fairfield, Swan Hunter, White, Yarrow Major Variants: J class, K class, N class, Q class, R class (new), S class (new), T class, U class, V class (new), W class (new), Z class, CA class, CH class, CO class, CR class, Weapon class Role: Fleet protection, reconnaissance, convoy escort Operated by: Royal Navy (Variants also Polish Navy, Royal Australian Navy, Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Netherlands Navy, Royal Norwegian Navy) First Laid Down: 26th August 1937 Last Completed: 12th September 1939 Units: HMS Jervis, HMS Jersey, HMS Jaguar, HMS Juno, HMS Jupiter, HMS Janus, HMS Jackal, HMS Javelin Released by ww2ships.com BRITISH DESTROYERS www.WW2Ships.com FEATURE ARTICLE J Class Fleet Destroyer © James Davies Contents CONTENTS J Class Fleet Destroyer............................................................................................................1 Key Information.......................................................................................................................1 Contents.....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction...............................................................................................................................3 Development.............................................................................................................................4 -

The Tidewater Confronts the Storm : Antisubmarine Warfare Off the Capes

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 1994 The idewT ater confronts the storm : antisubmarine warfare off the ac pes of Virginia during the first six months of 1942 Brett Leo olH land Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Holland, Brett Leo, "The ideT water confronts the storm : antisubmarine warfare off the capes of Virginia during the first six months of 1942" (1994). Master's Theses. 1178. http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses/1178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Thesis Title: The Tidewater Confronts the Storm: Antisubmarine Warf are off the Capes of Virginia during the First Six Months of 1942 Author: Brett Leo Holland Degree: Master of Arts in History School: University of Richmond Year Degree Awarded: May, 1994 Thesis Director: Dr. David Evans At the outbreak of the Second World War, Germany launched a devastating submarine campaign against the merchant marine traffic along the eastern seaboard of America. The antisubmarine defenses mounted by the United States were insufficient in the first months of 1942. This thesis examines how the United States Navy, in cooperation with the Army and the Coast Guard, began antisubmarine operations to protect the Chesapeake Bay and the surrounding area from the menace of Germany's U-boats during the first year of America's participation in World War II. -

HE Name "Mediterranean" Suggests the Importance of the Sea That T Bears It

CHAPTER 5 R.A.N. SHIPS OVERSEAS JUNE-DECEMBER 194 0 HE name "Mediterranean" suggests the importance of the sea that T bears it. Up to the last millennium B .C., it was the centre of th e known world ; a vast lake, washing the shores of three continents—Europe , Africa, and Asia—and both separating and linking the communities whic h grew and lived on its fringe . As such it became the main schoolhouse of navigation, of naval strategy, and naval tactics . On its surface, in the sea battles of the Persian, the Peloponnesian, and the Punic wars, the out - come of those wars was decided, and the fates of nations determined . With the expansion of the known world through exploration, the Mediterranean' s importance was enhanced as a main route to the East and as a highway for the trade on which were built the mercantile republics of Genoa and Venice. Over its surface sailed the fleets of the Crusaders ; it "has witnessed the clash of Christianity and Islam ; and its waters have been dyed with the blood of Goth and Vandal, Arab and Norman". Not until the ocean routes to the Far East and the Americas were opened in the fifteent h century was its monopoly destroyed . The largest of the world 's inland seas, it is some two thousand nautical miles long, by six hundred wide at its greatest width between the heel o f Italy and the southern shore of the Gulf of Sidra on the African coast. Its only oceanic opening is that at the western end to the Atlantic by th e Straits of Gibraltar, 8 miles in width . -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. ___X____ New Submission ________ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing World War II Shipwrecks along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) World War I U-boat Operations (28 July 1914 to 11 Nov. 1918) Interwar Period (1919-1939) World War II U-boat Operations Prior to U.S. Declaration of War (1 Sept.1939 – 8 Dec. 1941) Operation Drumbeat-Paukenschlag (1 Jan.-July 1942) U-Boat Battlefield Moves to Florida and the Gulf of Mexico (May 1942 – Feb. 1943) Final Years (April 1943 – May 1945) World War II Shipwrecks off the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico C. Form Prepared by: name/title Deborah Marx, Maritime Archaeologist and James Delgado, Ph.D, Director of Maritime Heritage organization NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries street & number 1305 East West Highway SSMC4 city or town Silver Spring state MD zip code 20910-3278 e-mail Deborah [email protected] telephone 781-545-8026 ex 214 date 4/26/2013 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. -

Introduction 1 the Royal Navy and the Home Fleet: Men, Material

Notes Introduction 1. P. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (London: Ashfield Press, 1995 revised paper back ed.), p. 306. 2. For a modern account informed by Italian language sources, see J. Greene and A. Massignani, The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940–1943 (Rochester, Kent: Chatham Publishing, 1998), pp. 63–81. 3. L. Kennedy, The Death of the Tirpitz (Boston: Little, Brown, 1979), p. 56 uses the term ‘much worry’; ‘bogeyman’ is from P. Kemp, Convoy! Drama in Arctic Waters (London: Arms Armour Press, 1993), p. 191; Rear Admiral W. H. Langenberg, USNR, in ‘The German Battleship Tirpitz: A Strategic Warship?’, Naval War College Review, 34 (4), p. 82, uses the term ‘concern’. See also T. Gallagher, The X-Craft Raid (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1969), chapter 2. 4. Langenberg, ‘The German Battleship Tirpitz’, p. 82. 1 The Royal Navy and the Home Fleet: Men, Material, Strategy 1919–39 1. This process is described in detail by P. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, pp. 205–37. However, the conventional view of naval policy ca 1900–14 has recently come under critical review; see, for example, J. T. Sumida, In Defence of Naval Supremacy (London: Routledge, 1993), N. Lambert, Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution (Columbia, SC: South Carolina University Press, 1999). Certainly, it was a cost-saving measure. But whether Britain employed a Dreadnought fleet or ‘flotilla defence’, it became clear between 1906 and 1912 that most of the Fleet would be needed in Home Waters if war with Germany erupted. -

NEWSFLASH April 2021

NEWSFLASH April 2021 Hello Swamp Foxes, welcome to the April 2021 Newsletter Into April we go....... another month has come and gone...... It is hard to figure just what 2021 has in store for Us, One Model at a Time I guess........... 9th April 2021 saw another Royal Navy Veteran Pass away, Prince Philip, The Duke of Edinburgh who had a very active service, passed away peacefully in his sleep aged 99, Fair Winds and Following Seas Sir..... Some great builds and works in progress by our members can be seen in members models, Stay Safe, Hang in there and .............. Keep on Building From the Front Office… Howdy, all! The April Zoom meeting will be held on 21 April: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81633790135?pwd=S1UwTVlaaU9tejEzZmNOZElza2FSdz09 Mike Roof will present a demonstration on rigging for us this month. Speaking with the library, they still have not opened up meeting rooms or re-started programs. I will continue to keep checking in with them from month to month to see when we might actually begin to meet in person again. I will also ask them if we might be able to hold a “tailgate meeting” in the front corner of their parking lot—as long as we do not cause traffic issues, I think it might be an alternative to the meeting room. I will let you know how that goes. Granted, with the famously hot Columbia summers getting big in the window, we won’t be able to do this every month, but it is a possibility. **** **** **** **** **** **** As far as the June show goes, everything is still progressing towards that date. -

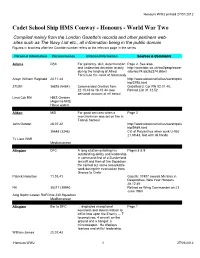

Cadet School Ship HMS Conway

Honours WW2 printed 27/01/2012 Cadet School Ship HMS Conway - Honours - World War Two Compiled mainly from the London Gazette's records and other pertinent web- sites such as The Navy List etc., all information being in the public domain Figures in brackets after the Gazette number refers to the relevant page in the series Personal Information Circumstances Citation/Information Sources & Comments Adams DSC For gallantry, skill, determination Page 2, See also: and undaunted devotion to duty http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar during the landing of Allied /stories/74/a5262374.shtml Forces on the coast of Normandy Alwyn William Reginald 24.11.44 http://www.uboat.net/allies/warships/s hip/3795.html 27/29? 36815 (5454) Commanded Orestes from Gazetted Lt Cdr RN 02.01.40, 22.10.43 to 16.10.44 (see Retired List 31.12.52 personal account at ref below) Lieut Cdr RN HMS Orestes (Algerine M/S) Home waters Aitken MiD For good services when a Page 2 merchantman was set on fire in Tobruk harbour John Gordon 28.07.42 http://www.uboat.net/allies/warships/s hip/5489.html 35648 (3346) CO of Polyanthus when sunk U-952 21.09.43, lost with all hands Ty Lieut RNR Mediterranean Alington DFC A long citation extolling his Pages 8 & 9 outstanding ability and leadership in command first of a Sunderland aircraft and then of the Squadron. He carried out some remarkable work during the evacuation from Greece to Crete Patrick Hamilton 11.08.41 Gazette 37407 awards Mention in Despatches, New Year Honours 28.12.45 NK 35217 (39940 Retired as Wing Commander on 23 June 1963 Actg Sqdrn Leader RAFONo 230 Squadron Mediterranean Alington Bar to DFC .