Submitting Changes to Voter Registrations Online to Disrupt Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rptr Bryant Edtr Rosen Americans at Risk

1 RPTR BRYANT EDTR ROSEN AMERICANS AT RISK: MANIPULATION AND DECEPTION IN THE DIGITAL AGE WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 8, 2020 House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Washington, D.C. The subcommittee met, pursuant to call, at 10:32 a.m., in Room 2123, Rayburn House Office Building, Hon. Jan Schakowsky [chairwoman of the subcommittee] presiding. Present: Representatives Schakowsky, Castor, Veasey, Kelly, O'Halleran, Lujan, Cardenas, Blunt Rochester, Soto, Matsui, McNerney, Dingell, Pallone (ex officio), Rodgers, Burgess, Latta, Guthrie, Bucshon, Hudson, Carter, and Walden (ex officio). Staff Present: Jeff Carroll, Staff Director; Evan Gilbert, Deputy Press Secretary; Lisa Goldman, Senior Counsel; Waverly Gordon, Deputy Chief Counsel; Tiffany Guarascio, 2 Deputy Staff Director; Alex Hoehn-Saric, Chief Counsel, Communications and Consumer Protection; Zach Kahan, Outreach and Member Service Coordinator; Joe Orlando, Staff Assistant; Alivia Roberts, Press Assistant; Chloe Rodriguez, Policy Analyst; Sydney Terry, Policy Coordinator; Anna Yu Professional Staff Member; Mike Bloomquist, Minority Staff Director; S.K. Bowen, Minority Press Assistant; William Clutterbuck, Minority Staff Assistant; Jordan Davis, Minority Senior Advisor; Tyler Greenberg, Minority Staff Assistant; Peter Kielty, Minority General Counsel; Ryan Long, Minority Deputy Staff Director; Mary Martin, Minority Chief Counsel, Energy & Environment & Climate Change; Brandon Mooney, Minority Deputy Chief Counsel, Energy; Brannon Rains, Minority Legislative Clerk; Zack Roday, Minority Communications Director; and Peter Spencer, Minority Senior Professional Staff Member, Environment & Climate Change. 3 Ms. Schakowsky. Good morning, everyone. The Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce will now come to order. We will begin with member statements, and I will begin by recognizing myself for 5 minutes. -

Lahima (Light As Cotton), Prapti (Attainment of Whatever You Desire) Lshatwan .(Lordliness), and Vasitwam (Control Over Everything)

THE MEHER MESSAGE [Vol. II] December, 1930 [ No. 12] An Avatar Meher Baba Trust eBook July 2020 All words of Meher Baba copyright © Avatar Meher Baba Perpetual Public Charitable Trust Ahmednagar, India Source: The Meher Message THE MEHERASHRAM INSTITUTE ARANGAON AHMEDNAGAR Proprietor and Editor.—Kaikhushru Jamshedji Dastur M.A., LL.B. eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust's eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non-facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust's web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba's lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. They have been created through a process of scanning the original pages, running these scans through optical character recognition (OCR) software, reflowing the new text, and proofreading it. Except in rare cases where we specify otherwise, the texts that you will find here correspond, page for page, with those of the original publications: in other words, page citations reliably correspond to those of the source books. But in other respects-such as lineation and font- the page designs differ. Our purpose is to provide digital texts that are more readily downloadable and searchable than photo facsimile images of the originals would have been. Moreover, they are often much more readable, especially in the case of older books, whose discoloration and deteriorated condition often makes them partly illegible. -

American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat

American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat Jerome P. Bjelopera Specialist in Organized Crime and Terrorism January 23, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41416 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat Summary This report describes homegrown violent jihadists and the plots and attacks that have occurred since 9/11. For this report, “homegrown” describes terrorist activity or plots perpetrated within the United States or abroad by American citizens, legal permanent residents, or visitors radicalized largely within the United States. The term “jihadist” describes radicalized individuals using Islam as an ideological and/or religious justification for their belief in the establishment of a global caliphate, or jurisdiction governed by a Muslim civil and religious leader known as a caliph. The term “violent jihadist” characterizes jihadists who have made the jump to illegally supporting, plotting, or directly engaging in violent terrorist activity. The report also discusses the radicalization process and the forces driving violent extremist activity. It analyzes post-9/11 domestic jihadist terrorism and describes law enforcement and intelligence efforts to combat terrorism and the challenges associated with those efforts. Appendix A provides details about each of the post-9/11 homegrown jihadist terrorist plots and attacks. There is an “executive summary” at the beginning that summarizes the report’s findings. Congressional -

December 31, 2007 Justin Levitt Analysis of Alleged Fraud in Briefs

December 31, 2007 Justin Levitt 1 Analysis of Alleged Fraud in Briefs Supporting Crawford Respondents In briefing filed with the Supreme Court in the Crawford v. Marion County Election Board case, the State of Indiana and several of its allied amici again fail to justify Indiana’s photo ID law. They recite various examples of problems that the challenged law would not solve. They fail, however, to provide any evidence that in-person impersonation fraud — the only misconduct that photo ID rules could possibly prevent — is a problem, let alone one justifying the burdens of a restrictive photo ID rule. In these submissions, it is easy to get distracted by noise. The briefs — submitted by the State of Indiana, the U.S. Department of Justice, the Attorney Generals of nine states, a national political party, members of Congress, various election officials, and several nonprofit organizations — contain more than 250 citations to reports of election problems. But not one of the sources cited shows proof of a vote that Indiana’s law could prevent. That is, not one of the citations offered by Indiana or its allies refers to a proven example of a single vote cast at the polls in someone else’s name that could be stopped by a pollsite photo ID rule. Even including suspected but unproven reports of fraud, the State and its allies have uncovered remarkably little evidence of any misconduct that Indiana’s law could prevent. Out of almost 400 million votes cast in general elections alone since 2000,2 the briefs cite one attempt at impersonation that was thwarted without a photo ID requirement, and nine unresolved cases where impersonation fraud at the polls was suspected but not proven.3 Nine possible examples out of hundreds of millions — and these nine cases might just as well have been due to clerical error. -

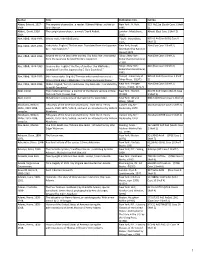

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

ENISA Threat Landscape Report 2017 15 Top Cyber-Threats and Trends

ENISA Threat Landscape Report 2017 15 Top Cyber-Threats and Trends FINAL VERSION 1.0 ETL 2017 JANUARY 2018 www.enisa.europa.eu European Union Agency For Network and Information Security ENISA Threat Landscape Report 2017 ETL 2017 | 1.0 | HSA | January 2018 About ENISA The European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA) is a centre of network and information security expertise for the EU, its member states, the private sector and Europe’s citizens. ENISA works with these groups to develop advice and recommendations on good practice in information security. It assists EU member states in implementing relevant EU legislation and works to improve the resilience of Europe’s critical information infrastructure and networks. ENISA seeks to enhance existing expertise in EU member states by supporting the development of cross-border communities committed to improving network and information security throughout the EU. More information about ENISA and its work can be found at www.enisa.europa.eu. Contact For queries on this paper, please use [email protected] For media enquiries about this paper, please use [email protected]. Acknowledgements ENISA would like to thank the members of the ENISA ETL Stakeholder group: Pierluigi Paganini, Chief Security Information Officer, IT, Paul Samwel, Banking, NL, Jason Finlayson, Consulting, IR, Stavros Lingris, CERT, EU, Jart Armin, Worldwide coalitions/Initiatives, International, Thomas Häberlen, Member State, DE, Neil Thacker, Consulting, UK, Shin Adachi, Security Analyst, US, R. Jane Ginn, Consulting, US, Andreas Sfakianakis, Industry, NL. The group has provided valuable input, has supported the ENISA threat analysis and has reviewed ENISA material. -

Complaints by Name Based on Attorney General Consumer Complaints

Complaints By Name Based on Attorney General Consumer Complaints BusinessName id 29595 101 Auto Body Shop LLC/Used & Seized 1 1&1 Internet Inc 9 1&1 Mail & Media Inc 2 11th Avenue Investment Properties 1 11th Avenue Investment Property LLC 2 16906 17th Ave 2 1-800-Flowers 5 1-800-Pack-Rat 2 1800Wheelchair.com 1 1880 Western Wear / Western by Design 9 1 Moore Ag LLC 2 1st Ave Auto Transport 2 1st Class Paving 1 1stdibs.com 2 1 Stop Bedrooms 2 1StopBedrooms.com 2 1 Stop Services Towing & Recovery 2 1st Security Bank of Washington 11 1st United Consultants/United We Stand A 1 Chance Page 1 of 242 10/01/2021 Complaints By Name Based on Attorney General Consumer Complaints Chance 206 Maids 2 2-10 Home Buyers Warranty 2 2-10 Home Buyers Warranty/HBW Warranty 6 Administration 21st Century Insurance 1 21st Mortgage Corp. 1 21st Mortgage Corporation 1 23andme 3 23andMe Inc 4 24/7 Locksmith 3 24/7 Locksmith Services 1 24/7 Locksmith / US 1 Locksmith 1 24/7 Seattle Locksmith 1 24 Hour Fitness 95 24 Hour Garage Doors & Gates Services 2 24 Hour Glass Services LLC 2 24 Hour Services 2 24 Pet Watch / Pethealth 1 2 Sons Plumbing 2 30 Minute Hit 2 311 Tactical Solutions Inc 1 Page 2 of 242 10/01/2021 Complaints By Name Based on Attorney General Consumer Complaints 3:16 Construction 3 321Loans dba Helping America Group 1 32 Pearls Dental Clinic 2 360 Auto Body 1 360 K9 Training 3 360 Mortgage Group LLC 2 360training.com 2 38th Street Service Center 2 3 Day Blinds LLC 2 3G Collect To Cell 1 3 Monkeys Digital Media fka Emerald Screens 4 3six0 Motorsports -

Famous Impostors

d FAMOUS IMPOSTORS . • « gUEKN KUXABKTII AS A VOL'NG WOMAN FAMOUS IMPOSTORS BY BRAM STOKER REMINISCENCES OP AUTHOR OF "DRAOTLA," " PERSONAL HENRY IRVING," ETC., ETC. ILLUSTRATED « • », IWcw Uorft STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY 1910 All rights reserved Copyright 1910 By BRAM STOKER Set up and electrotyped. Published November. 1910 T • • » • t . « . » • • * PREFACE The subject of imposture is always an interest- ing one, and impostors in one shape or another are likely to flourish as long as human nature remains what it is, and society shows itself ready to be gulled. The histories of famous cases of im- posture in this book have been grouped together to show that the art has been practised in many forms —impersonators, pretenders, swindlers, and hum- bugs of all kinds; those who have masqueraded in order to acquire wealth, position, or fame, and those who have done so merely for the love of the art. So numerous are instances, indeed, that the book cannot profess to exhaust a theme which might easily fill a dozen volumes; its purpose is simply to collect and record a number of the best known instances. The author, nevertheless, whose largest experience has lain in the field of fiction, has aimed at dealing with his material as with the material for a novel, except that all the facts given are real and authentic. He has made no attempt to treat the subject ethically; yet from a study of these impostors, the objects they had in view, the means they adopted, the risks they ran, and the punishments which attended exposure, any reader can draw his own conclusions.