The Fullness of Time: Christological Interventions Into Scientific Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Konturen VI (2014) 1

Konturen VI (2014) 1 Introduction: Defining the Human and the Animal Alexander Mathäs University of Oregon Foreword: First, I would like to thank the contributors to this special volume of Konturen: Defining the Human and the Animal. All the authors presented drafts of their manuscripts at a conference on this topic, which took place on May 2 and 3, 2013 at the University of Oregon. I am grateful to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the Oregon Humanities Center, the Journal of Comparative Literature, the Univeristy of Oregon’s College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Philosophy, Department of Comparative Literature, the German Studies Committee, and the Department of German and Scandinavian for their generous support. Without them both the conference and the ensuing publication would not have been possible. Special thanks go to my departmental colleagues, and foremost to my Department Head and Chair of the German Studies Committee, Jeffrey Librett, who gave me the opportunity to publish this volume. I am grateful for the support of Alexis Smith, Eva Hofmann, Stephanie Chapman, and Judith Lechner, who assisted me at various stages of the project. I am also indebted to the graduate students who participated in a class on Human-Animal borders that I taught in Winter 2013. Sarah Grew’s assistance with the web design is greatly appreciated. And I would like to thank our office staff, above all Barbara Ver West and Joshua Heath, who were of great help in organizing and advertising the conference. Introduction: In recent years the fairly new field of Animal Studies has received considerable attention (see bibliography). -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Convergent Recruitment of Proteins Into Animal Venoms

ANRV386-GG10-22 ARI 7 August 2009 8:22 The Toxicogenomic Multiverse: Convergent Recruitment of Proteins Into Animal Venoms Bryan G. Fry,1 Kim Roelants,2,∗,∗∗ Donald E. Champagne,3 Holger Scheib,4 Joel D.A. Tyndall,5 Glenn F. King,6 Timo J. Nevalainen,7 Janette A. Norman,8,∗∗ Richard J. Lewis,6 Raymond S. Norton,9,∗∗ Camila Renjifo,10 and Ricardo C. Rodrıguez´ de la Vega11 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bio21 Institute, University of Melbourne, Melbourne 3010 Australia; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2009. Key Words 10:483–511 toxin, phylogeny, evolution, convergence First published online as a Review in Advance on July 16, 2009 Abstract The Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics Throughout evolution, numerous proteins have been convergently is online at genom.annualreviews.org recruited into the venoms of various animals, including centipedes, This article’s doi: cephalopods, cone snails, fish, insects (several independent venom sys- 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164356 tems), platypus, scorpions, shrews, spiders, toxicoferan reptiles (lizards Copyright c 2009 by Annual Reviews. and snakes), and sea anemones. The protein scaffolds utilized con- by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 10/08/09. For personal use only. All rights reserved vergently have included AVIT/colipase/prokineticin, CAP, chitinase, 1527-8204/09/0922-0483$20.00 cystatin, defensins, hyaluronidase, Kunitz, lectin, lipocalin, natriuretic ∗ See page 511 for coauthor affiliations. peptide, peptidase S1, phospholipase A2, sphingomyelinase D, and Annu. Rev. Genom. Human Genet. 2009.10:483-511. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org SPRY. Many of these same venom protein types have also been con- vergently recruited for use in the hematophagous gland secretions of invertebrates (e.g., fleas, leeches, kissing bugs, mosquitoes, and ticks) and vertebrates (e.g., vampire bats). -

The Philosophical and Historical Roots of Evolutionary Tree Diagrams

Evo Edu Outreach (2011) 4:515–538 DOI 10.1007/s12052-011-0355-0 HISTORYAND PHILOSOPHY Depicting the Tree of Life: the Philosophical and Historical Roots of Evolutionary Tree Diagrams Nathalie Gontier Published online: 19 August 2011 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011 Abstract It is a popularly held view that Darwin was the were the result of this blend would, from the nineteenth first author to draw a phylogenetic tree diagram. However, century onward, also include the element of time. The as is the case with most popular beliefs, this one also does recognition of time would eventually lead to the recognition not hold true. Firstly, Darwin never called his diagram of of evolution as a fact of nature, and subsequently, tree common descent a tree. Secondly, even before Darwin, tree iconographies would come to represent exclusively the diagrams were used by a variety of philosophical, religious, evolutionary descent of species. and secular scholars to depict phenomena such as “logical relationships,”“affiliations,”“genealogical descent,”“af- Keywords Species classification . Evolutionary finity,” and “historical relatedness” between the elements iconography. Tree of life . Networks . Diagram . Phylogeny. portrayed on the tree. Moreover, historically, tree diagrams Genealogy. Pedigree . Stammbaum . Affinity. Natural themselves can be grouped into a larger class of diagrams selection that were drawn to depict natural and/or divine order in the world. In this paper, we trace the historical roots and cultural meanings of these tree diagrams. It will be Introduction demonstrated that tree diagrams as we know them are the outgrowth of ancient philosophical attempts to find the In this paper, we focus on the “why” of tree iconography. -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 History Systematics has its origins in two threads of biological science: classification and evolution. The organization of natural variation into sets, groups, and hierarchies traces its roots to Aristotle and evolution to Darwin. Put simply, systematization of nature can and has progressed in absence of causative theories relying on ideas of “plan of nature,” divine or otherwise. Evolutionists (Darwin, Wallace, and others) proposed a rationale for these patterns. This mixture is the foundation of modern systematics. Originally, systematics was natural history. Today we think of systematics as being a more inclusive term, encompassing field collection, empirical compar- ative biology, and theory. To begin with, however, taxonomy, now known as the process of naming species and higher taxa in a coherent, hypothesis-based, and regular way, and systematics were equivalent. Roman bust of Aristotle (384–322 BCE) 1.1 Aristotle Systematics as classification (or taxonomy) draws its Western origins from Aris- totle1. A student of Plato at the Academy and reputed teacher of Alexander the Great, Aristotle founded the Lyceum in Athens, writing on a broad variety of topics including what we now call biology. To Aristotle, living things (species) came from nature as did other physical classes (e.g. gold or lead). Today, we refer to his classification of living things (Aristotle, 350 BCE) that show simi- larities with the sorts of classifications we create now. In short, there are three featuresCOPYRIGHTED of his methodology that weMATERIAL recognize immediately: it was functional, binary, and empirical. Aristotle’s classification divided animals (his work on plants is lost) using Ibn Rushd (Averroes) functional features as opposed to those of habitat or anatomical differences: “Of (1126–1198) land animals some are furnished with wings, such as birds and bees.” Although he recognized these features as different in aspect, they are identical in use. -

Ernst Haeckel and the Morphology of Ethics Nolan Hele

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 19:41 Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Ernst Haeckel and the Morphology of Ethics Nolan Hele Volume 15, numéro 1, 2004 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/012066ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/012066ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) The Canadian Historical Association/La Société historique du Canada ISSN 0847-4478 (imprimé) 1712-6274 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Hele, N. (2004). Ernst Haeckel and the Morphology of Ethics. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, 15(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.7202/012066ar Tous droits réservés © The Canadian Historical Association/La Société Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des historique du Canada, 2004 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ chajournal2004.qxd 12/01/06 14:11 Page 1 Ernst Haeckel and the Morphology of Ethics NOLAN HEIE n 10 May 1907, Johannes Reinke,1 a Professor of botany at the University Oof Kiel and member of the Prussian upper chamber, the -

Joseph Krauskopf's Evolution and Judaism

The University of Manchester Research Joseph Krauskopf’s Evolution and Judaism: One Reform Rabbi’s Response to Scepticism and Materialism in Nineteenth-century North America DOI: 10.31826/9781463237141-012 Document Version Final published version Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Langton, D. (2015). Joseph Krauskopf’s Evolution and Judaism: One Reform Rabbi’s Response to Scepticism and Materialism in Nineteenth-century North America. Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies, 12, 122-130. https://doi.org/10.31826/9781463237141-012 Published in: Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:10. Oct. 2021 EDITOR Daniel R. Langton ASSISTANT EDITOR Simon Mayers Title: Joseph Krauskopf’s Evolution and Judaism: One Reform Rabbi’s Response to Scepticism and Materialism in Nineteenth-century North America Author(s): DANIEL R. -

Ernst Haeckel's Embryological Illustrations

Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud Ernst Haeckel’s Embryological Illustrations By Nick Hopwood* ABSTRACT Comparative illustrations of vertebrate embryos by the leading nineteenth-century Dar- winist Ernst Haeckel have been both highly contested and canonical. Though the target of repeated fraud charges since 1868, the pictures were widely reproduced in textbooks through the twentieth century. Concentrating on their first ten years, this essay uses the accusations to shed light on the novelty of Haeckel’s visual argumentation and to explore how images come to count as proper representations or illegitimate schematics as they cross between the esoteric and exoteric circles of science. It exploits previously unused manuscripts to reconstruct the drawing, printing, and publishing of the illustrations that attracted the first and most influential attack, compares these procedures to standard prac- tice, and highlights their originality. It then explains why, though Haeckel was soon ac- cused, controversy ignited only seven years later, after he aligned a disciplinary struggle over embryology with a major confrontation between liberal nationalism and Catholicism—and why the contested pictures nevertheless survived. INETEENTH-CENTURY IMAGES OF EVOLUTION powerfully and controversially N shape our view of the world. In 1997 a British developmental biologist accused the * Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge, Free School Lane, Cambridge CB2 3RH, United Kingdom. Research for this essay was supported by the Wellcome Trust and partly carried out in the departments of Lorraine Daston and Hans-Jo¨rg Rheinberger at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. My greatest debt is to the archivists of the Ernst-Haeckel-Haus, Jena: the late Erika Krauße gave generous help and invaluable advice over many years, and Thomas Bach, her successor as Kustos, provided much assistance with this project. -

Ernst Haeckel's Monistic Religon

ERNST HAECKEL'S MONISTIC RELIGION BY NILESR. HOLT For some of his contemporaries, the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) was the "nihilistic yet superstitious prophet of a new religion."' Others saw him as a vindicator who would confirm the triumph of science in its nineteenth-century warfare with religion. For still others, he was the "apostle of Darwinism," the major crusader on the European continent for the acceptance of Darwinism. Charles Darwin wrote that if one of Haeckel's works had appeared before his own The Descent of Man (1871), "I should probably never have com- pleted it. Almost all of the conclusions at which I have arrived I find confirmed by ... this naturalist, whose knowledge on many points is fuller than mine."2 Unlike some exponents of Darwinism, Haeckel's own consequential achievements in morphology and embryology pre- vented him from being dismissed as merely another of "Darwin's bull- dogs." From a position of scientific eminence, as professor of zoology at the University of Jena, Haeckel combined his activities to promote Darwinism with popularizations of his own "Monism." He presented Monism as a scientific movement which was based on Darwinism and 'This particular description is from "Popular Science in Germany," The Nation, DCXV (1879), 179-80. Haeckel's hopes to make of his Monism an international move- ment were heightened by interest in his Monistic system in the United States to the point that Paul Carus, editor of the Monist, attempted to distinguish between Haeckel's and that journal's "Monism." See the early correspondence between Carus and Haeckel, published as "Professor Haeckel's Monism and the Ideas of God and Im- mortality," Open Court, V (1891), 2957-58. -

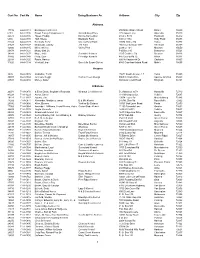

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

Teaching Gender with Libraries and Archives the Power of Information

Teaching Gender with Libraries and Archives The Power of Information i5 Libraries 00 book.indb 1 2013.10.04. 9:49 Titles in the Series: 1. Teaching with Memories. European Women’s Histories in International and Interdisciplinary Classrooms 2. Teaching Gender, Diversity and Urban Space. An Intersectional Approach between Gender Studies and Spatial Disciplines 3. Teaching Gender in Social Work 4. Teaching Subjectivity. Travelling Selves for Feminist Pedagogy 5. Teaching with the Third Wave. New Feminists’ Explorations of Teaching and Institutional Contexts 6. Teaching Visual Culture in an Interdisciplinary Classroom. Feminist (Re)Interpretations of the Field 7. Teaching Empires. Gender and Transnational Citizenship in Europe 8. Teaching Intersectionality. Putting Gender at the Centre 9. Teaching “Race” with a Gendered Edge 10. Teaching Gender with Libraries and Archives The Power of Information Title 1 is published by ATHENA2 and Women’s Studies Centre, National University of Ireland, Gal- way; Titles 2–8 are published by ATHENA3 Advanced Thematic Network in Women’s Studies in Europe, University of Utrecht and Centre for Gender Studies, Stockholm University; Title 9-10 are jointly published by ATGENDER, The European Association for Gender Research, Edu- cation and Documentation, Utrecht and Central European University Press, Budapest. i5 Libraries 00 book.indb 2 2013.10.04. 9:49 Edited by Sara de Jong and Sanne Koevoets Teaching Gender with Libraries and Archives The Power of Information Teaching with Gender. European Women’s Studies in International and Interdisciplinary Classrooms A book series by ATGENDER ATGENDER. The European Association for Gender Research, Education and Documentation Utrecht & Central European University Press Budapest–New York i5 Libraries 00 book.indb 3 2013.10.04. -

Hint Fiction: an Anthology of Stories in 25 Words Or Fewer / Edited by Robert Swartwood.—1St Ed

Further praise for Hint Fiction “The stories in Robert Swartwood’s Hint Fiction have some serious velocity. Some explode, some needle, some bleed, and some give the reader room to dream. They’re fun and addictive, like puzzles or haiku or candy. I’ve finished mine but I want more.” —Stewart O’Nan *hint fiction hint fiction An Anthology of Stories in 25 Words or Fewer Edited by Robert Swartwood W. W. NORTON & COMPANY * New York London “Before Perseus” by Ben White. First published in PicFic, October 30, 2009. “Claim” by Gwendolyn Joyce Mintz. First published in Sexy Stranger, February 2006, issue 4. “Corrections & Clarifications” by Robert Swartwood. First published in elimae, October 2008. “Found Wedged in the Side of a Desk Drawer in Paris, France, 23 December 1989” by Nick Mamatas. First published in Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, May 2003, issue 12. “Free Enterprise” by Kelly Spitzer. First published in elimae, December 2007. “The End or the Beginning” by James Frey © Big Jim Industries. “The Mall” by Robley Wilson © Blue Garage Co. “The Widow’s First Year” by Joyce Carol Oates © Ontario Review, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Robert Swartwood Individual contributions copyright © by the contributor All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hint fiction: an anthology of stories in 25 words or fewer / edited by Robert Swartwood.—1st ed. p. cm. ISBN: 978-0-393-34022-8 1. Short stories, American. 2. American fiction—21st century. I. Swartwood, Robert. PS648.S5H56 2010 813'.010806—dc22 2010016056 W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y.