1 Did Goethe and Schelling Endorse Species Evolution?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embodied Empiricism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PhilPapers Embodied Empiricism CHARLES T. WOLFE OFER GAL It was in 1660s England, according to the received view, in the meetings of the Royal Society of London, that science acquired the form of empirical enquiry that we recognize as our own: an open, collaborative experimental practice, mediated by specially-designed instruments, supported by civil, critical discourse, stressing accuracy and replicability. Guided by the philosophy of Francis Bacon, by Protestant ideas of this-worldly benevolence, by gentlemanly codes of decorum and integrity and by a dominant interest in mechanics and a conviction in the mechanical structure of the universe, the members of the Royal Society created a novel experimental practice that superseded all former modes of empirical inquiry– from Aristotelian observations to alchemical experimentation. It is enlightening to consider that this view is imparted by both the gentlemen of the Royal Society, in their official self-presentations, and by much of the most iconoclastic historiography of our time. Lines like ―Boyle‘s example … was mobilized to give legitimacy to the experimental philosophy,‖1 are strongly reminiscent of Bishop Sprat‘s 1667 eulogy of the ―Lord Bacon in whose Books there are everywhere scattered the best arguments for the defence of experimental philosophy; and the best directions, needful to promote it.‖2 One reason for the surprising agreement is that this picture of openness, benevolence and civility does capture some of the moral-epistemological mores of the empiricism of the New Science, but this very agreement of historians and apologists also harbors a paradox. -

Why Was There No Controversy Over Life in the Scientific Revolution? *

Why was there no controversy over Life in the Scientific Revolution? * Charles T. Wolfe Unit for History and Philosophy of Science University of Sydney Well prior to the invention of the term ‗biology‘ in the early 1800s by Lamarck and Treviranus, and also prior to the appearance of terms such as ‗organism‘ under the pen of Leibniz in the early 1700s, the question of ‗Life‘, that is, the status of living organisms within the broader physico-mechanical universe, agitated different corners of the European intellectual scene. From modern Epicureanism to medical Newtonianism, from Stahlian animism to the discourse on the ‗animal economy‘ in vitalist medicine, models of living being were constructed in opposition to ‗merely anatomical‘, structural, mechanical models. It is therefore curious to turn to the ‗passion play‘ of the Scientific Revolution – whether in its early, canonical definitions or its more recent, hybridized, reconstructed and expanded versions: from Koyré to Biagioli, from Merton to Shapin – and find there a conspicuous absence of worry over what status to grant living beings in a newly physicalized universe. Neither Harvey, nor Boyle, nor Locke (to name some likely candidates, the latter having studied with Willis and collaborated with Sydenham) ever ask what makes organisms unique, or conversely, what does not. In this paper I seek to establish how ‗Life‘ became a source of contention in early modern thought, and how the Scientific Revolution missed the controversy. ―Of all natural forces, vitality is the incommunicable one.‖ (Fitzgerald 1945: 74) Introduction To ask why there was no controversy over Life – that is, debates specifically focusing on the status of living beings, their mode of functioning, their internal mechanisms and above all their ‗uniqueness‘ within the physical universe as a whole – in the Scientific Revolution is to simultaneously run the risk of extreme narrowness of detail and/or of excessive breadth in scope. -

Foucault's Darwinian Genealogy

genealogy Article Foucault’s Darwinian Genealogy Marco Solinas Political Philosophy, University of Florence and Deutsches Institut Florenz, Via dei Pecori 1, 50123 Florence, Italy; [email protected] Academic Editor: Philip Kretsedemas Received: 10 March 2017; Accepted: 16 May 2017; Published: 23 May 2017 Abstract: This paper outlines Darwin’s theory of descent with modification in order to show that it is genealogical in a narrow sense, and that from this point of view, it can be understood as one of the basic models and sources—also indirectly via Nietzsche—of Foucault’s conception of genealogy. Therefore, this essay aims to overcome the impression of a strong opposition to Darwin that arises from Foucault’s critique of the “evolutionistic” research of “origin”—understood as Ursprung and not as Entstehung. By highlighting Darwin’s interpretation of the principles of extinction, divergence of character, and of the many complex contingencies and slight modifications in the becoming of species, this essay shows how his genealogical framework demonstrates an affinity, even if only partially, with Foucault’s genealogy. Keywords: Darwin; Foucault; genealogy; natural genealogies; teleology; evolution; extinction; origin; Entstehung; rudimentary organs “Our classifications will come to be, as far as they can be so made, genealogies; and will then truly give what may be called the plan of creation. The rules for classifying will no doubt become simpler when we have a definite object in view. We possess no pedigrees or armorial bearings; and we have to discover and trace the many diverging lines of descent in our natural genealogies, by characters of any kind which have long been inherited. -

Handlungsspielräume Von Frauen in Weimar-Jena Um 1800. Sophie Mereau, Johanna Schopenhauer, Henriette Von Egloffstein

Handlungsspielräume von Frauen in Weimar-Jena um 1800. Sophie Mereau, Johanna Schopenhauer, Henriette von Egloffstein Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt dem Rat der Philosophischen Fakultät der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena von Julia Frindte geboren am 15. Juni 1976 in Erfurt Gutachter 1. Prof . Dr. Siegrid Westphal 2. Prof. Dr. Georg Schmidt 3. ....................................................................... Tag des Kolloquiums: 12.12.2005 Inhalt 1. EINLEITUNG ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 FRAGESTELLUNG................................................................................................. 3 1.2 UNTERSUCHUNGSGEGENSTAND .......................................................................... 6 1.3 FORSCHUNGSSTAND ............................................................................................10 1.4 QUELLENGRUNDLAGE .........................................................................................17 1.5 VORGEHENSWEISE...............................................................................................25 2. DAS KONZEPT ‚HANDLUNGSSPIELRAUM’...........................................................28 2.1 HANDLUNGSSPIELRAUM IN ALLTAGSSPRACHE UND FORSCHUNG .......................29 2.2 DAS KONZEPT ‚HANDLUNGSSPIELRAUM’ ...........................................................38 2.2.1 Begriffsverwendung............................................................................38 -

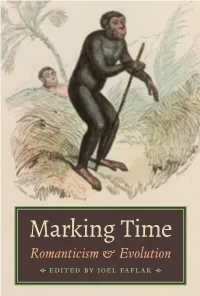

Faflak 5379 6208 0448F Final Pass.Indd

Marking Time Romanticism & Evolution EditEd by JoEl FaFlak MARKING TIME Romanticism and Evolution EDITED BY JOEL FAFLAK Marking Time Romanticism and Evolution UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2017 Toronto Buffalo London www.utorontopress.com ISBN 978-1-4426-4430-4 (cloth) Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Marking time : Romanticism and evolution / edited by Joel Faflak. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4430-4 (hardcover) 1. Romanticism. 2. Evolution (Biology) in literature. 3. Literature and science. I. Faflak, Joel, 1959–, editor PN603.M37 2017 809'.933609034 C2017-905010-9 CC-BY-NC-ND This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivative License. For permission to publish commercial versions please contact University of Tor onto Press. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario. Funded by the Financé par le Government gouvernement of Canada du Canada Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction – Marking Time: Romanticism and Evolution 3 joel faflak Part One: Romanticism’s Darwin 1 Plants, Analogy, and Perfection: Loose and Strict Analogies 29 gillian beer 2 Darwin and the Mobility of Species 45 alan bewell 3 Darwin’s Ideas 68 matthew rowlinson Part Two: Romantic Temporalities 4 Deep Time in the South Pacifi c: Scientifi c Voyaging and the Ancient/Primitive Analogy 95 noah heringman 5 Malthus Our Contemporary? Toward a Political Economy of Sex 122 maureen n. -

Presidential Address

Empowering Philosophy Christia Mercer COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Presidential Address delivered at the one hundred sixteenth Eastern Division meeting of the American Philosophical Association in Philadelphia, PA, on January 10, 2020. The main goal of my presidential address in January 2020 was to show that philosophy’s past offers a means to empower its present. I hoped to encourage colleagues to make the philosophy we teach and practice more inclusive (both textually and topically) and to adopt a more public- facing engagement with our discipline. As I add these introductory remarks to my January lecture, it is June 2020 and the need to empower philosophy has never seemed more urgent. We’ve witnessed both the tragic death of George Floyd and the popular uprising of a diverse group of Americans in response to the ongoing violence against Black lives. Many white Americans—and many philosophers—have begun to realize that their inattentiveness to matters of diversity and inclusivity must now be seen as more than mere negligence. Recent demonstrations frequently contain signs that make the point succinctly: “Silence is violence.” A central claim of my January lecture was that philosophy’s status quo is no longer tenable. Even before the pandemic slashed university budgets and staff, our employers were cutting philosophy programs, enrollments were shrinking, and jobs were increasingly hard to find. Despite energetic attempts on the part of many of our colleagues to promote a more inclusive approach to our research and teaching, the depressing truth remains: -

Montesquieu Charles-Louis De Secondat

EBSCOhost Page 1 of 5 Record: 1 Title: Montesquieu, Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de. Authors: Robert Shackleton Source: Britannica Biographies; 2008, p1, 2p Document Type: Biography Abstract: (born January 18, 1689, Château La Brède, near Bordeaux, France— died February 10, 1755, Paris) French political philosopher whose major work, The Spirit of Laws, was a major contribution to political theory. [ABSTRACT FROM PUBLISHER] Copyright of Britannica Biographies is the property of Encyclopedia Britannica and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. This abstract may be abridged. No warranty is given about the accuracy of the copy. Users should refer to the original published version of the material for the full abstract. (Copyright applies to all abstracts.) Lexile: 1240 Full Text Word Count:2611 Accession Number: 32418468 Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition Montesquieu, Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de (born January 18, 1689, Château La Brède, near Bordeaux, France—died February 10, 1755, Paris) French political philosopher whose major work, The Spirit of Laws, was a major contribution to political theory. Early life and career. His father, Jacques de Secondat, belonged to an old military family of modest wealth that had been ennobled in the 16th century for services to the crown, while his mother, Marie- Françoise de Pesnel, was a pious lady of partial English extraction. She brought to her husband a great increase in wealth in the valuable wine-producing property of La Brède. -

Konturen VI (2014) 1

Konturen VI (2014) 1 Introduction: Defining the Human and the Animal Alexander Mathäs University of Oregon Foreword: First, I would like to thank the contributors to this special volume of Konturen: Defining the Human and the Animal. All the authors presented drafts of their manuscripts at a conference on this topic, which took place on May 2 and 3, 2013 at the University of Oregon. I am grateful to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the Oregon Humanities Center, the Journal of Comparative Literature, the Univeristy of Oregon’s College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Philosophy, Department of Comparative Literature, the German Studies Committee, and the Department of German and Scandinavian for their generous support. Without them both the conference and the ensuing publication would not have been possible. Special thanks go to my departmental colleagues, and foremost to my Department Head and Chair of the German Studies Committee, Jeffrey Librett, who gave me the opportunity to publish this volume. I am grateful for the support of Alexis Smith, Eva Hofmann, Stephanie Chapman, and Judith Lechner, who assisted me at various stages of the project. I am also indebted to the graduate students who participated in a class on Human-Animal borders that I taught in Winter 2013. Sarah Grew’s assistance with the web design is greatly appreciated. And I would like to thank our office staff, above all Barbara Ver West and Joshua Heath, who were of great help in organizing and advertising the conference. Introduction: In recent years the fairly new field of Animal Studies has received considerable attention (see bibliography). -

Oil Sketches and Paintings 1660 - 1930 Recent Acquisitions

Oil Sketches and Paintings 1660 - 1930 Recent Acquisitions 2013 Kunsthandel Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com My special thanks go to Sabine Ratzenberger, Simone Brenner and Diek Groenewald, for their research and their work on the text. I am also grateful to them for so expertly supervising the production of the catalogue. We are much indebted to all those whose scholarship and expertise have helped in the preparation of this catalogue. In particular, our thanks go to: Sandrine Balan, Alexandra Bouillot-Chartier, Corinne Chorier, Sue Cubitt, Roland Dorn, Jürgen Ecker, Jean-Jacques Fernier, Matthias Fischer, Silke Francksen-Mansfeld, Claus Grimm, Jean- François Heim, Sigmar Holsten, Saskia Hüneke, Mathias Ary Jan, Gerhard Kehlenbeck, Michael Koch, Wolfgang Krug, Marit Lange, Thomas le Claire, Angelika and Bruce Livie, Mechthild Lucke, Verena Marschall, Wolfram Morath-Vogel, Claudia Nordhoff, Elisabeth Nüdling, Johan Olssen, Max Pinnau, Herbert Rott, John Schlichte Bergen, Eva Schmidbauer, Gerd Spitzer, Andreas Stolzenburg, Jesper Svenningsen, Rudolf Theilmann, Wolf Zech. his catalogue, Oil Sketches and Paintings nser diesjähriger Katalog 'Oil Sketches and Paintings 2013' erreicht T2013, will be with you in time for TEFAF, USie pünktlich zur TEFAF, the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht. 14. - 24. März 2013. TEFAF runs from 14-24 March 2013. Die in dem Katalog veröffentlichten Gemälde geben Ihnen einen The selection of paintings in this catalogue is Einblick in das aktuelle Angebot der Galerie. Ohne ein reiches Netzwerk an designed to provide insights into the current Beziehungen zu Sammlern, Wissenschaftlern, Museen, Kollegen, Käufern und focus of the gallery’s activities. -

Readingsample

Evolutionary Theory and the Creation Controversy Bearbeitet von Olivier Rieppel 1st Edition. 2010. Buch. x, 204 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 642 14895 8 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 1060 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Chemie, Biowissenschaften, Agrarwissenschaften > Biowissenschaften allgemein > Evolutionsbiologie Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Chapter 2 The Problem of Change An evolving world is a world of change. A created world does not change. It just is. Or if it seems to change, the change is only apparent, as it is preconceived and preordained by the blueprint of Creation. Change is paradoxical: how can something change and yet remain the same? How much remodeling can be done to a house before we no longer call it the same house, but a new and different one? Some Ancient Greek philosophers solved the ‘problem of change’ through the concept of dynamic permanence: planets are in constant motion, continuously changing their position relative to other heavenly bodies, but they travel in immutable, eternal orbits. These orbits can be described in terms of universal laws of nature, which in turn can be expressed in the timeless language of mathematics. The concept of dynamic permanence is less easily applied to organisms. The developing chicken appears to change continuously, but here, organs such as the heart, the brain, and the limbs seem to come into existence without having been apparent before. -

The Philosophical and Historical Roots of Evolutionary Tree Diagrams

Evo Edu Outreach (2011) 4:515–538 DOI 10.1007/s12052-011-0355-0 HISTORYAND PHILOSOPHY Depicting the Tree of Life: the Philosophical and Historical Roots of Evolutionary Tree Diagrams Nathalie Gontier Published online: 19 August 2011 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011 Abstract It is a popularly held view that Darwin was the were the result of this blend would, from the nineteenth first author to draw a phylogenetic tree diagram. However, century onward, also include the element of time. The as is the case with most popular beliefs, this one also does recognition of time would eventually lead to the recognition not hold true. Firstly, Darwin never called his diagram of of evolution as a fact of nature, and subsequently, tree common descent a tree. Secondly, even before Darwin, tree iconographies would come to represent exclusively the diagrams were used by a variety of philosophical, religious, evolutionary descent of species. and secular scholars to depict phenomena such as “logical relationships,”“affiliations,”“genealogical descent,”“af- Keywords Species classification . Evolutionary finity,” and “historical relatedness” between the elements iconography. Tree of life . Networks . Diagram . Phylogeny. portrayed on the tree. Moreover, historically, tree diagrams Genealogy. Pedigree . Stammbaum . Affinity. Natural themselves can be grouped into a larger class of diagrams selection that were drawn to depict natural and/or divine order in the world. In this paper, we trace the historical roots and cultural meanings of these tree diagrams. It will be Introduction demonstrated that tree diagrams as we know them are the outgrowth of ancient philosophical attempts to find the In this paper, we focus on the “why” of tree iconography. -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 History Systematics has its origins in two threads of biological science: classification and evolution. The organization of natural variation into sets, groups, and hierarchies traces its roots to Aristotle and evolution to Darwin. Put simply, systematization of nature can and has progressed in absence of causative theories relying on ideas of “plan of nature,” divine or otherwise. Evolutionists (Darwin, Wallace, and others) proposed a rationale for these patterns. This mixture is the foundation of modern systematics. Originally, systematics was natural history. Today we think of systematics as being a more inclusive term, encompassing field collection, empirical compar- ative biology, and theory. To begin with, however, taxonomy, now known as the process of naming species and higher taxa in a coherent, hypothesis-based, and regular way, and systematics were equivalent. Roman bust of Aristotle (384–322 BCE) 1.1 Aristotle Systematics as classification (or taxonomy) draws its Western origins from Aris- totle1. A student of Plato at the Academy and reputed teacher of Alexander the Great, Aristotle founded the Lyceum in Athens, writing on a broad variety of topics including what we now call biology. To Aristotle, living things (species) came from nature as did other physical classes (e.g. gold or lead). Today, we refer to his classification of living things (Aristotle, 350 BCE) that show simi- larities with the sorts of classifications we create now. In short, there are three featuresCOPYRIGHTED of his methodology that weMATERIAL recognize immediately: it was functional, binary, and empirical. Aristotle’s classification divided animals (his work on plants is lost) using Ibn Rushd (Averroes) functional features as opposed to those of habitat or anatomical differences: “Of (1126–1198) land animals some are furnished with wings, such as birds and bees.” Although he recognized these features as different in aspect, they are identical in use.