From Locke to Materialism: Empiricism, the Brain and the Stirrings of Ontology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Denying a Dualism: Goodman's Repudiation of the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction

Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 28, 2004, 226-238. Denying a Dualism: Goodman’s Repudiation of the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction Catherine Z. Elgin The analytic synthetic/distinction forms the backbone of much modern Western philosophy. It underwrites a conception of the relation of representations to reality which affords an understanding of cognition. Its repudiation thus requires a fundamental reconception and perhaps a radical revision of philosophy. Many philosophers believe that the repudiation of the analytic/synthetic distinction and kindred dualisms constitutes a major loss, possibly even an irrecoverable loss, for philosophy. Nelson Goodman thinks otherwise. He believes that it liberates philosophy from unwarranted restrictions, creating opportunities for the development of powerful new approaches to and reconceptions of seemingly intractable problems. In this article I want to sketch some of the consequences of Goodman’s reconception. My focus is not on Goodman’s reasons for denying the dualism, but on some of the ways its absence affects his position. I do not contend that the Goodman obsessed over the issue. I have no reason to think that the repudiation of the distinction was a central factor in his intellectual life. But by considering the function that the analytic/synthetic distinction has performed in traditional philosophy, and appreciating what is lost and gained in repudiating it, we gain insight into Goodman’s contributions. I begin then by reviewing the distinction and the conception of philosophy it supports. The analytic/synthetic distinction is a distinction between truths that depend entirely on meaning and truths that depend on both meaning and fact. In the early modern period, it was cast as a distinction between relations of ideas and matters of fact. -

The Atheist's Bible: Diderot's 'Éléments De Physiologie'

The Atheist’s Bible Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie Caroline Warman In off ering the fi rst book-length study of the ‘Éléments de physiologie’, Warman raises the stakes high: she wants to show that, far from being a long-unknown draf , it is a powerful philosophical work whose hidden presence was visible in certain circles from the Revolut on on. And it works! Warman’s study is original and st mulat ng, a historical invest gat on that is both rigorous and fascinat ng. —François Pépin, École normale supérieure, Lyon This is high-quality intellectual and literary history, the erudit on and close argument suff used by a wit and humour Diderot himself would surely have appreciated. —Michael Moriarty, University of Cambridge In ‘The Atheist’s Bible’, Caroline Warman applies def , tenacious and of en wit y textual detect ve work to the case, as she explores the shadowy passage and infl uence of Diderot’s materialist writ ngs in manuscript samizdat-like form from the Revolut onary era through to the Restorat on. —Colin Jones, Queen Mary University of London ‘Love is harder to explain than hunger, for a piece of fruit does not feel the desire to be eaten’: Denis Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie presents a world in fl ux, turning on the rela� onship between man, ma� er and mind. In this late work, Diderot delves playfully into the rela� onship between bodily sensa� on, emo� on and percep� on, and asks his readers what it means to be human in the absence of a soul. -

Religious Worldviews*

RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEWS* SECULAR POLITICAL CHRISTIANITY ISLAM MARXISM HUMANISM CORRECTNESS Nietzsche/Rorty Sources Koran, Hadith Humanist Manifestos Marx/Engels/Lenin/Mao/ The Bible Foucault/Derrida, Frankfurt Sunnah I/II/ III Frankfurt School Subjects School Theism Theism Atheism Atheism Atheism THEOLOGY (Trinitarian) (Unitarian) PHILOSOPHY Correspondence/ Pragmatism/ Pluralism/ Faith/Reason Dialectical Materialism (truth) Faith/Reason Scientism Anti-Rationalism Moral Relativism Moral Absolutes Moral Absolutes Moral Relativism Proletariat Morality (foster victimhood & ETHICS (Individualism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) /Collectivism) Creationism Creationism Naturalism Naturalism Naturalism (Intelligence, Time, Matter, (Intelligence, Time Matter, ORIGIN SCIENCE (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) Energy) Energy) 1 Mind/Body Dualism Monism/self-actualization Socially constructed self Monism/behaviorism Mind/Body Dualism (fallen) PSYCHOLOGY (non fallen) (tabula rasa) Monism (tabula rasa) (tabula rasa) Traditional Family/Church/ Polygamy/Mosque & Nontraditional Family/statist Destroy Family, church and Classless Society/ SOCIOLOGY State State utopia Constitution Anti-patriarchy utopia Critical legal studies Proletariat law Divine/natural law Shari’a Positive law LAW (Positive law) (Positive law) Justice, freedom, order Global Islamic Theocracy Global Statism Atomization and/or Global & POLITICS Sovereign Spheres Ummah Progressivism Anarchy/social democracy Stateless Interventionism & Dirigisme Stewardship -

Philosophical Logic 2018 Course Description (Tentative) January 15, 2018

Philosophical Logic 2018 Course description (tentative) January 15, 2018 Valentin Goranko Introduction This 7.5 hp course is mainly intended for students in philosophy and is generally accessible to a broad audience with basic background on formal classical logic and general appreciation of philosophical aspects of logic. Practical information The course will be given in English. It will comprise 18 two-hour long sessions combining lectures and exercises, grouped in 2 sessions per week over 9 teaching weeks. The weekly pairs of 2-hour time slots (incl. short breaks) allocated for these sessions, will be on Mondays during 10.00-12.00 and 13.00-15.00, except for the first lecture. The course will begin on Wednesday, April 4, 2018 (Week 14) at 10.00 am in D220, S¨odra huset, hus D. Lecturer's info: Name: Valentin Goranko Email: [email protected] Homepage: http://www2.philosophy.su.se/goranko Course webpage: http://www2.philosophy.su.se/goranko/Courses2018/PhilLogic-2018.html Prerequisites The course will be accessible to a broad audience with introductory background on classical formal logic. Some basic knowledge of modal logics would be an advantage but not a prerequisite. Brief description Philosophical logic studies a variety of non-classical logical systems intended to formalise and reason about various philosophical concepts and ideas. They include a broad family of modal logics, as well as many- valued, intuitionistic, relevant, conditional, non-monotonic, para-consistent, etc. logics. Modal logics extend classical logic with additional intensional logical operators, reflecting different modes of truth, including alethic, epistemic, doxastic, temporal, deontic, agentive, etc. -

Introduction to Philosophy. Social Studies--Language Arts: 6414.16. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 086 604 SO 006 822 AUTHOR Norris, Jack A., Jr. TITLE Introduction to Philosophy. Social Studies--Language Arts: 6414.16. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 20p.; Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; Grade 10; Grade 11; Grade 12; *Language Arts; Learnin4 Activities; *Logic; Non Western Civilization; *Philosophy; Resource Guides; Secondary Grades; *Social Studies; *Social Studies Units; Western Civilization IDENTIFIERS *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT Western and non - western philosophers and their ideas are introduced to 10th through 12th grade students in this general social studies Quinmester course designed to be used as a preparation for in-depth study of the various schools of philosophical thought. By acquainting students with the questions and categories of philosophy, a point of departure for further study is developed. Through suggested learning activities the meaning of philosopky is defined. The Socratic, deductive, inductive, intuitive and eclectic approaches to philosophical thought are examined, as are three general areas of philosophy, metaphysics, epistemology,and axiology. Logical reasoning is applied to major philosophical questions. This course is arranged, as are other quinmester courses, with sections on broad goals, course content, activities, and materials. A related document is ED 071 937.(KSM) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY U S DEPARTMENT EDUCATION OF HEALTH. NAT10N41 -

WAS SUMAROKOV a LOCKEAN SENSUALIST? on Locke's Reception in Eighteenth-Century Russia

Part One. Sumarokov and the Literary Process of His Time 8 WAS SUMAROKOV A LOCKEAN SENSUALIST? On Locke’s Reception in Eighteenth-Century Russia Despite the fact that Locke occupied a central place in European En- lightenment thought, his works were little known in Russia. Locke is often listed among those important seventeenth-century figures including Ba- con, Spinoza, Gassendi, and Hobbes, whose ideas formed the intellectual background for the Petrine reforms; Prokopovich, Kantemir, Tatishchev and perhaps Peter himself were acquainted with Locke’s ideas, but for most Russians in the eighteenth century Locke was little more than an illustrious name. Locke’s one book that did have a palpable impact was his Some Thoughts Concerning Education, translated by Nikolai Popovskii from a French version, published in 1759 and reprinted in 1788.1 His draft of a textbook on natural science was also translated, in 1774.2 Yet though Locke as pedagogue was popular, his reception in Russia, as Marc Raeff has noted, was overshadowed by the then current “infatuation with Rousseau’s pedagogical ideas.”3 To- ward the end of the century some of Locke’s philosophical ideas also held an attraction for Russian Sentimentalists, with their new interest in subjective 1 The edition of 1760 was merely the 1759 printing with a new title page (a so- called “titul’noe izdanie”). See the Svodnyi katalog russkli knigi grazhdanskoi pechati, 5 vols. (Мoscow: Gos. biblioteka SSSR imeni V. I. Lenina, 1962–674), II, 161–2, no. 3720. 2 Elements of Natural Philosophy, translated from the French as Pervonachal’nyia osno va niia fiziki (Svodnyi katalog, II, 62, no. -

Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World

Reconciling Eros and Neuroscience: Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World by ANDREW J. PELLITIERI* Boston University Abstract Many people currently working in the sciences of the mind believe terms such as “love” will soon be rendered philosophically obsolete. This belief results from a common assumption that such terms are irreconcilable with the naturalistic worldview that most modern scientists might require. Some philosophers reject the meaning of the terms, claiming that as science progresses words like ‘love’ and ‘happiness’ will be replaced completely by language that is more descriptive of the material phenomena taking place. This paper attempts to defend these meaningful concepts in philosophy of mind without appealing to concepts a materialist could not accept. Introduction hilosophy engages the meaning of the word “love” in a myriad of complex discourses ranging from ancient musings on happiness, Pto modern work in the philosophy of mind. The eliminative and reductive forms of materialism threaten to reduce the importance of our everyday language and devalue the meaning we attach to words like “love,” in the name of scientific progress. Faced with this threat, some philosophers, such as Owen Flanagan, have attempted to defend meaningful words and concepts important to the contemporary philosopher, while simultaneously promoting widespread acceptance of materialism. While I believe that the available work is useful, I think * [email protected]. Received 1/2011, revised December 2011. © the author. Arché Undergraduate Journal of Philosophy, Volume V, Issue 1: Winter 2012. pp. 60-82 RECONCILING EROS AND NEUROSCIENCE 61 more needs to be said about the functional role of words like “love” in the script of progressing neuroscience, and further the important implications this yields for our current mode of practical reasoning. -

Hegel and Aristotle

This page intentionally left blank HEGEL AND ARISTOTLE Hegel is, arguably, the most difficult of all philosophers. To find a way through his thought, interpreters have usually approached him as though he were developing Kantian and Fichtean themes. This book is the first to demonstrate in a systematic way that it makes much more sense to view Hegel’s idealism in relation to the metaphysical and epis- temological tradition stemming from Aristotle. This book offers an account of Hegel’s idealism and in particular his notions of reason, subjectivity, and teleology, in light of Hegel’s inter- pretation, discussion, assimilation, and critique of Aristotle’s philoso- phy. It is the first systematic analysis comparing Hegelian and Aris- totelian views of system and history; being, metaphysics, logic, and truth; nature and subjectivity; spirit, knowledge, and self-knowledge; ethics and politics. In addition, Hegel’s conception of Aristotle’s phi- losophy is contrasted with alternative conceptions typical of his time and ours. No serious student of Hegel can afford to ignore this major new in- terpretation. Moreover, because it investigates with enormous erudi- tion the relation between two giants of the Western philosophical tra- dition, this book will speak to a wider community of readers in such fields as history of philosophy and history of Aristotelianism, meta- physics and logic, philosophy of nature, psychology, ethics, and politi- cal science. Alfredo Ferrarin is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Boston University. MODERN EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY General Editor Robert B. Pippin, University of Chicago Advisory Board Gary Gutting, University of Notre Dame Rolf-Peter Horstmann, Humboldt University, Berlin Mark Sacks, University of Essex This series contains a range of high-quality books on philosophers, top- ics, and schools of thought prominent in the Kantian and post-Kantian European tradition. -

Differentiating Neuroethics from Neurophilosophy

Differentiating Neuroethics From Neurophilosophy A review of Scientific and Philosophical Perspectives in Neuroethics by James J. Giordano and Bert Gordijn (Eds.) New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 388 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-70303-1. $50.00 Reviewed by Amir Raz Hillel Braude Neuroethics is about gaps: the gap between neuroscience and ethics, the one between science and philosophy, and, most of all, the “hard gap” between mind and brain. The hybrid term neuroethics, put into public circulation by the late William Safire (2002), attempts to address these lacunae through an emergent discipline that draws equally from neuroscience and philosophy. What, however, distinguishes neuroethics from its sister discipline—neurophilosophy? Contrary to traditional “armchair” philosophy, neurophilosophers such as Paul and Patricia Churchland argue that philosophy needs to take account of empirical neuroscience data regarding the mind–brain relation. Similarly, neuropsychologists and neuroscientists should be amenable to philosophical insights and the conceptual rigor of the philosophical method. Joshua Greene’s neuroimaging studies of participants making moral decisions provide a good example of this symbiotic relation between neuroscience and philosophy (Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001). A number of possible answers to the distinction between neuroethics and neurophilosophy emerge from Scientific and Philosophical Perspectives in Neuroethics, edited by James J. Giordano and Bert Gordijn. First, neuroethics emerges from the discipline of bioethics and, as such, specifically deals with ethical issues related to neuroscience. As Neil Levy says in his preface to the book, “Techniques and technologies stemming from the science of the mind raise . profound questions about what it means to be human, and pose greater challenges to moral thought” (p. -

Newton.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag

omslag Newton.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag. 1 e Dutch Republic proved ‘A new light on several to be extremely receptive to major gures involved in the groundbreaking ideas of Newton Isaac Newton (–). the reception of Newton’s Dutch scholars such as Willem work.’ and the Netherlands Jacob ’s Gravesande and Petrus Prof. Bert Theunissen, Newton the Netherlands and van Musschenbroek played a Utrecht University crucial role in the adaption and How Isaac Newton was Fashioned dissemination of Newton’s work, ‘is book provides an in the Dutch Republic not only in the Netherlands important contribution to but also in the rest of Europe. EDITED BY ERIC JORINK In the course of the eighteenth the study of the European AND AD MAAS century, Newton’s ideas (in Enlightenment with new dierent guises and interpre- insights in the circulation tations) became a veritable hype in Dutch society. In Newton of knowledge.’ and the Netherlands Newton’s Prof. Frans van Lunteren, sudden success is analyzed in Leiden University great depth and put into a new perspective. Ad Maas is curator at the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands. Eric Jorink is researcher at the Huygens Institute for Netherlands History (Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences). / www.lup.nl LUP Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 1 Newton and the Netherlands Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 2 Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. -

Leibniz's Ultimate Theory Soshichi Uchii Abstract

Leibniz’s Ultimate Theory Soshichi Uchii Abstract This is a short summary of my new interpretation of Leibniz’s philosophy, including metaphysics and dynamics. Monadology is the core of his philosophy, but according to my interpretation, this document must be read together with his works on dynamics and geometry Analysis Situs, among others. Monadology describes the reality, the world of monads. But in addition, it also contains a theory of information in terms of the state transition of monads, together with a sketch of how that information is transformed into the phenomena via coding. I will argue that Leibniz’s program has a surprisingly wide range, from classical physics to the theories of relativity (special and general) , and extending even to quantum mechanics. 1. How should we read Monadology? Among Leibniz’s papers he completed in his last years, the one that should be regarded as containing the core of his system of knowledge is Monadology (1714). It is a theory of metaphysics, but I take it that Leibniz thought that it is the foundation of dynamics, and he envisaged that dynamics should be combined with his new geometry, called Analysis Situs. There are two firm grounds for the preceding assertion. The first is that Leibniz sketched the relationship between his metaphysics and dynamics, in the two papers New System and Specimen Dynamicum (both published in 1695; English tr. in Ariew and Garber 1989). If we wish to figure out a reasonable interpretation of Monadology, this ground must be taken very seriously. The second ground is the amazing accomplishments shown in The Metaphysical Foundations of Mathematics (written around the same time as Monadology; English tr. -

Introduction to Philosophy

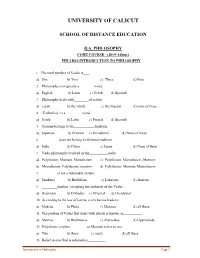

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION B.A. PHILOSOPHY CORE COURSE - (2019-Admn.) PHL1 B01-INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 1. The total number of Vedas is . a) One b) Two c) Three d) Four 2. Philosophy is originally a word. a) English b) Latin c) Greek d) Spanish 3. Philosophy deals with of reality. a) a part b) the whole c) the illusion d) none of these 4. ‘Esthetikos’ is a word. a) Greek b) Latin c) French d) Spanish 5. Taoism belongs to the tradition. a) Japanese b) Oriental c) Occidental d) None of these 6. does not belong to Oriental tradition. a) India b) China c) Japan d) None of these 7. Vedic philosophy evolved in the order. a) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism c) Polytheism, Monotheism, Monism b) Monotheism, Polytheism, monism d) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism 8. is not a heterodox system. a) Samkhya b) Buddhism c) Lokayata d) Jainism 9. implies ‘accepting the authority of the Vedas’. a) Heterodox b) Orthodox c) Oriental d) Occidental 10. According to the law of karma, every karma leads to . a) Moksha b) Phala c) Dharma d) all these 11. The portion of Vedas that deals with rituals is known as . a) Mantras b) Brahmanas c) Aranyakas d) Upanishads 12. Polytheism implies as Monism refers to one. a) Two b) three c) many d) all these 13. Belief in one God is referred as . Introduction to Philosophy Page 1 a) Henotheism b) Monotheism c) Monism d) Polytheism 14. Samkhya propounded . a) Dualism b) Monism c) Monotheism d) Polytheism 15. is an Oriental system.