Effect of Cooking Loss in the Assessment of Vitamin Intake for Epidemiological Data in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R Graphics Output

Dexamethasone sodium phosphate ( 0.339 ) Melengestrol acetate ( 0.282 ) 17beta−Trenbolone ( 0.252 ) 17alpha−Estradiol ( 0.24 ) 17alpha−Hydroxyprogesterone ( 0.238 ) Triamcinolone ( 0.233 ) Zearalenone ( 0.216 ) CP−634384 ( 0.21 ) 17alpha−Ethinylestradiol ( 0.203 ) Raloxifene hydrochloride ( 0.203 ) Volinanserin ( 0.2 ) Tiratricol ( 0.197 ) trans−Retinoic acid ( 0.192 ) Chlorpromazine hydrochloride ( 0.191 ) PharmaGSID_47315 ( 0.185 ) Apigenin ( 0.183 ) Diethylstilbestrol ( 0.178 ) 4−Dodecylphenol ( 0.161 ) 2,2',6,6'−Tetrachlorobisphenol A ( 0.156 ) o,p'−DDD ( 0.155 ) Progesterone ( 0.152 ) 4−Hydroxytamoxifen ( 0.151 ) SSR150106 ( 0.149 ) Equilin ( 0.3 ) 3,5,3'−Triiodothyronine ( 0.256 ) 17−Methyltestosterone ( 0.242 ) 17beta−Estradiol ( 0.24 ) 5alpha−Dihydrotestosterone ( 0.235 ) Mifepristone ( 0.218 ) Norethindrone ( 0.214 ) Spironolactone ( 0.204 ) Farglitazar ( 0.203 ) Testosterone propionate ( 0.202 ) meso−Hexestrol ( 0.199 ) Mestranol ( 0.196 ) Estriol ( 0.191 ) 2,2',4,4'−Tetrahydroxybenzophenone ( 0.185 ) 3,3,5,5−Tetraiodothyroacetic acid ( 0.183 ) Norgestrel ( 0.181 ) Cyproterone acetate ( 0.164 ) GSK232420A ( 0.161 ) N−Dodecanoyl−N−methylglycine ( 0.155 ) Pentachloroanisole ( 0.154 ) HPTE ( 0.151 ) Biochanin A ( 0.15 ) Dehydroepiandrosterone ( 0.149 ) PharmaCode_333941 ( 0.148 ) Prednisone ( 0.146 ) Nordihydroguaiaretic acid ( 0.145 ) p,p'−DDD ( 0.144 ) Diphenhydramine hydrochloride ( 0.142 ) Forskolin ( 0.141 ) Perfluorooctanoic acid ( 0.14 ) Oleyl sarcosine ( 0.139 ) Cyclohexylphenylketone ( 0.138 ) Pirinixic acid ( 0.137 ) -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2012/0202780 A1 Gavin Et Al

US 20120202780A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2012/0202780 A1 Gavin et al. (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 9, 2012 (54) CARRIER COMPOSITION Publication Classification (76) Inventors: Paul David Gavin, Chadstone (51) Int. Cl. (AU); Mahmoud El-Tamimy, A6II 47/24 (2006.01) Meadow Heights (AU); Jeremy A6II 3/196 (2006.01) James Cottrell, Caulfield South A6IP5/00 (2006.01) (AU); Giacinto Gaetano, South A 6LX 3/573 (2006.01) Melbourne (AU); Nicholas John A6IP 23/00 (2006.01) Kennedy, Boronia (AU) A6IP 29/00 (2006.01) A6II 3/167 (2006.01) (21) Appl. No.: 13/501,494 A63L/407 (2006.01) (22) PCT Fled: Dec. 22, 2010 (52) U.S. Cl. ......... 514/180: 514/785: 514/788: 514/772: 514/626; 514/567; 514/413: 514/179 (86) PCT NO.: S371 (c)(1), (57) ABSTRACT (2), (4) Date: Apr. 12, 2012 A carrier composition of the present invention comprises a phosphate compound of an electron transfer agent and a rela Related U.S. Application Data tively high concentration of a polar protic solvent. A biologi (60) Provisional application No. 61/289,507, filed on Dec. cally active compound may be formulated with a carrier com 23, 2009. position of the present invention to provide a formulation. Patent Application Publication Aug. 9, 2012 Sheet 1 of 5 US 2012/0202780 A1 - - if solvent E. -ie-20% solvent 3. ". S. .t E FGURE 1 Patent Application Publication Aug. 9, 2012 Sheet 2 of 5 US 2012/0202780 A1 -H 10 LC2 s -C- 20 ulcm2 . - a 30 ulcm2 t E re FIGURE 2A HO licm2 80i -o- 20 ul/cm2 'i -A-30 ul/cm2 140 EO 10 8 8 4) O O FIGURE 2B Patent Application Publication Aug. -

Vitamins a and E and Carotenoids

Fat-Soluble Vitamins & Micronutrients: Vitamins A and E and Carotenoids Vitamins A (retinol) and E (tocopherol) and the carotenoids are fat-soluble micronutrients that are found in many foods, including some vegetables, fruits, meats, and animal products. Fish-liver oils, liver, egg yolks, butter, and cream are known for their higher content of vitamin A. Nuts and seeds are particularly rich sources of vitamin E (Thomas 2006). At least 700 carotenoids—fat-soluble red and yellow pigments—are found in nature (Britton 2004). Americans consume 40–50 of these carotenoids, primarily in fruits and vegetables (Khachik 1992), and smaller amounts in poultry products, including egg yolks, and in seafoods (Boylston 2007). Six major carotenoids are found in human serum: alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, beta-cryptoxanthin, lutein, trans-lycopene, and zeaxanthin. Major carotene sources are orange-colored fruits and vegetables such as carrots, pumpkins, and mangos. Lutein and zeaxanthin are also found in dark green leafy vegetables, where any orange coloring is overshadowed by chlorophyll. Trans-Lycopene is obtained primarily from tomato and tomato products. For information on the carotenoid content of U.S. foods, see the 1998 carotenoid database created by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Nutrition Coordinating Center at the University of Minnesota (http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/car98/car98.html). Vitamin A, found in foods that come from animal sources, is called preformed vitamin A. Some carotenoids found in colorful fruits and vegetables are called provitamin A; they are metabolized in the body to vitamin A. Among the carotenoids, beta-carotene, a retinol dimer, has the most significant provitamin A activity. -

Biological and Biochemical Studies on the Effect of Vitamin a And

Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 5(4): 102-110, 2011 ISSN 1991-8178 Effect of Vitamin A and Iodine Status on Thyroid Gland Functions in Rats Zakia Mostafa Abdel-kader, Heba Barakat, Rasha Hamed Mahmoud and Nehad Naem Shosha Department of Biochemistry and Nutrition, Women's College, Ain Shams University Abstract: Vitamin A (VA) deficiency (VAD) and iodine deficiency (ID) disorders (IDD) are major global public health problems, mostly affecting women of reproductive age and young children. The present study aims to investigate the effect of iodine and VA (deficient, sufficient or supplement) alone and in combination on of thyroid gland functions in hypothyroid rat model. 60 weaning male albino rats were fed on VA and iodine deficient diet for 4 weeks to induce hypothyroidism. Then they were divided into six groups, 10 rats per group. Each group received different diet which differs in their content of iodine and VA for a consecutive 2 weeks. These groups were compared with 20 control rats. Serum TSH, TT4, FT4, TT3, and FT3 were measured to estimate the efficiency of each diet on treatment of hypothyroidism. Also, serum retinol was measured to determine the influence of VA in replenishing VA deficiency status. Moreover, hepatic and serum lipid profiles, serum glucose, and hepatic glycogen were estimated to detect the effect of thyroid gland functions on cardiovascular disease and carbohydrate metabolism. The results showed that, however VA alone was effective in improvement TSH level; it had no effect on thyroid gland function. Whereas, when VA was in combination with iodine in the sufficient diet, they significantly promoted the normalization of thyroid gland functions than iodine alone. -

Conversion Factors for Vitamin a and Carotenoids

NEW! CONVERSION FACTORS FOR VITAMIN A AND CAROTENOIDS Vitamin A and carotenoids can be quanti- fied in several different units, but it is preferable to use the International System of Units (SI) such as µmol: SI Units Commonly Used Units 1µmol retinol (vitamin A) = 286 µg retinol (vitamin A) 1µmol β-carotene = 537 µg β-carotene Supplements, food, and animal feed: 0.00349 µmol retinol (vitamin A) = 1µg retinol (vitamin A) 1.15 µg retinyl acetate 1.83 µg retinyl palmitate 3.33 IU (1 IU = 0.3 µg) For example, vitamin A in an oil supplement: 209 µmol retinol (vitamin A) = 200,000 IU 60,000 µg retinol (vitamin A) Retinol concentrations in: Serum: 1 µmol/L = 28.6 µg/dL Liver: 1 µmol/g = 286 µg/g Milk: 1 µmol/L = 28.6 µg/dL Fat: 1 µmol/g = 286 µg/g Unit conversion for commonly used cutoff values for serum retinol (vitamin A) concentration: 0.35 µmol/L = 10 µg/dL 0.70 µmol/L = 20 µg/dL 1.05 µmol/L = 30 µg/dL INTERNATIONAL VITAMIN A CONSULTATIVE GROUP (IVACG) RETINOL ACTIVITY EQUIVALENT The term “retinol activity equivalent” (RAE) was introduced by the U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM)1 to replace “retinol equivalent” (RE) used by FAO/ WHO2 to take into account new research on the vitamin A activity (bioefficacy) of carotenoids. The IOM deemed carotenoid bioefficacy in mixed foods eaten by healthy people in developed countries to be half the required amount set by FAO/WHO. Bioefficacy may, in fact, be even lower in popula- tions in developing countries.3 References: 1. -

Risk Assessment of Vitamin a (Retinol and Retinyl Esters) in Cosmetics

Risk assessment of vitamin A (retinol and retinyl esters) in cosmetics Opinion of the Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids, Materials in Contact with Food and Cosmetics of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety Date: 22.08.12 Doc. no.: 10-405-3 final ISBN: 978-82-8259-059-4 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) 10/405-3 final Risk assessment of vitamin A (retinol and retinyl esters) in cosmetics Ragna Bogen Hetland (Chair) Berit Granum Claus Lützow-Holm Jan Ludvig Lyche Jan Erik Paulsen Vibeke Thrane 2 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) 10/405-3 final Contributors Persons working for VKM, either as appointed members of the Committee or as ad hoc experts, do this by virtue of their scientific expertise, not as representatives for their employers. The Civil Services Act instructions on legal competence apply for all work prepared by VKM. Acknowledgements The Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (Vitenskapskomiteen for mattrygghet, VKM) has appointed a working group consisting of both VKM members and external experts to answer the request from the Norwegian Food Safety Authority. The members of the working group are acknowledged for their valuable work on this opinion. The members of the working group are: VKM members Ragna Bogen Hetland, Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids, Materials in Contact with Food and Cosmetics (Chair) Berit Granum, Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids, Materials in Contact with Food and Cosmetics Jan Ludvig -

Skinceuticals Retinol 0.3 “As an Expert in Facial Rejuvenation, Retinol Would Definitely Be at the Top of My List,” Says Dr

here are many different voices to turn to when seeking advice regarding anti-aging skincare, but some are undeniably more qualified than others. While we do love a good Reddit thread or Twitter chain for discovering new recommendations, they don’t carry quite the same weight as a medical professional’s informed input. To help sort through the clutter, we reached out to two plastic surgeons working closely with anti- aging for their top tips on which home products help most. Dr. Melissa Doft, M.D. and Konstantin Vasyukevich, M.D. shared their picks for which ingredients—and which products containing them—are most effective, even outside of the clinic. 1 Retinol: SkinCeuticals Retinol 0.3 “As an expert in facial rejuvenation, Retinol would definitely be at the top of my list,” says Dr. Vasyukevich, known to his patients as Dr. K. “It is one of the most effective ingredients for a sustainable skin rejuvenating effect. The only caveat being that it has to be applied on a regular basis for an extended period of time, otherwise it becomes ineffective.” He recommends SkinCeuticals Retinol 0.3 (seen above) for nighttime use, and MZ Skin’s Hydrate & Nourish Age Defence Retinol Day Moisturizer SPF30 ($149; net-a-porter.com) for use during the day. To buy: $67; dermstore.com. 2 Vitamin C: Timeless Skin Care 20% Vitamin C Serum + Vitamin E + Ferulic Acid Dr. Doft agrees that retinol is a critical ingredient in home care, but also recommends another popular antioxidant. “For anti-aging my two top ingredients are retinol and vitamin C. -

Retinol, Retinoids and Tretinoin: What's the Difference?

What You Need to Know About Retinol Products Retinol, Retinoids and Tretinoin: What's the Difference? Retinol (the entire vitamin A molecule) can be broken down into more potent compounds, which are referred to as retinoids. Although the terms vitamin A, retinol, and retinoid often are used interchangeably, each has its own distinctive actions and regulations. For example, some forms of retinol can be used freely in cosmetics, while others (retinoids) can be obtained only by prescription. A few points to help clarify it for you: Retinol is a cosmetic ingredient that any cosmetics company can include in its products. It does not require a prescription. Other effective forms of cosmetic-grade vitamin A that you'll see in cosmetics include retinyl acetate, retinyl palmitate, and retinaldehyde, among others. Retinol is effective because when absorbed into your skin, it is broken down and converted into retinoic acid. Retinoic acid is the compound that actually can affect skin cells and their behavior. Both the cosmetic forms and the prescription forms of vitamin A can cause irritation, but, as you would expect, the highest risk of irritation is with the prescription forms (retinoids). Prescription retinoids include retinoic acid also called Tretinoin, the active ingredient in Renova and Retin-A. Is Retinol the Best Anti-Aging Ingredient? Despite retinol's many benefits, it is important to remember that no single ingredient can take care of all of the skin's complex needs. For example, despite retinol's superstar status, it does not eliminate the need for a well-formulated sunscreen, for an alpha hydroxy (glycolic, malic, citric or lactic) acid or beta hydroxy (salicylic) acid product for exfoliation, for a gentle cleanser, or for a serum or moisturizer loaded with antioxidants. -

IAEA Factsheet: How the Retinol Isotope Dilution Test Can Help

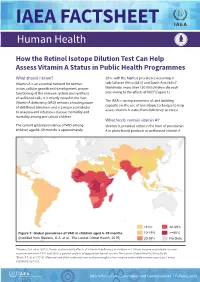

IAEA FACTSHEET Human Health How the Retinol Isotope Dilution Test Can Help Assess Vitamin A Status in Public Health Programmes What should I know? 29%, with the highest prevalence occurring in Vitamin A is an essential nutrient for normal sub-Saharan Africa (48%) and South Asia (44%)1. vision, cellular growth and development, proper Worldwide, more than 150 000 children die each functioning of the immune system and synthesis year owing to the effects of VAD2 [Figure 1]. of red blood cells. It is mostly stored in the liver. The IAEA is raising awareness of, and building Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) remains a leading cause capacity on, the use of an isotopic technique to help of childhood blindness and is a major contributor assess vitamin A status from deficiency to excess. to anaemia and infectious disease morbidity and mortality among pre-school children. What foods contain vitamin A? The current global prevalence of VAD among Vitamin A, provided either in the form of provitamin children aged 6–59 months is approximately A in plant-based products or preformed vitamin A <10% 40-59% Figure 1: Global prevalence of VAD in children aged 6–59 months 10-19% >=60% (modified from Stevens, G.A. et al., The Lancet Global Health, 2015) 20-39% No Data 1Stevens, G.A. et al. (2015). Trends and mortality effects of vitamin A deficiency in children in 138 low-income and middle-income countries between 1991 and 2013: a pooled analysis of population-based surveys. The Lancet Global Health 3(9):e528-36. 2Black, R.E. -

Simultaneous LC/MS Analysis of Carotenoids and Fat-Soluble Vitamins in Costa Rican Avocados (Persea Americana Mill.)

molecules Article Simultaneous LC/MS Analysis of Carotenoids and Fat-Soluble Vitamins in Costa Rican Avocados (Persea americana Mill.) Carolina Cortés-Herrera 1,*, Andrea Chacón 1, Graciela Artavia 1 and Fabio Granados-Chinchilla 2 1 Centro Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos, Universidad de Costa Rica, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, 11501-2060 San José, Costa Rica; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (G.A.) 2 Centro de Investigación en Nutrición Animal (CINA), Universidad de Costa Rica, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, 11501-2060 San José, Costa Rica; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +506-2511-7226 Academic Editor: Severina Pacifico Received: 26 August 2019; Accepted: 5 October 2019; Published: 10 December 2019 Abstract: Avocado (a fruit that represents a billion-dollar industry) has become a relevant crop in global trade. The benefits of eating avocados have also been thoroughly described as they contain important nutrients needed to ensure biological functions. For example, avocados contain considerable amounts of vitamins and other phytonutrients, such as carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene), which are fat-soluble. Hence, there is a need to assess accurately these types of compounds. Herein we describe a method that chromatographically separates commercial standard solutions containing both fat-soluble vitamins (vitamin A acetate and palmitate, Vitamin D2 and D3, vitamin K1, α-, δ-, and γ-vitamin E isomers) and carotenoids (β-cryptoxanthin, zeaxanthin, lutein, β-carotene, and lycopene) effectively (i.e., analytical recoveries ranging from 80.43% to 117.02%, for vitamins, and from 43.80% 1 to 108.63%). -

Retinol 4500 IU and Colecalciferol 450 IU

Braille Detail TOR Title: Retinol 4500 IU and Colecalciferol GENERICS r e t i n o l a n d 450 IU Capsules Retinol and Ref: RETCOL/TG/V1 Client: Tor Generics / Sabine De Swaaf c o l e c a l c i f e r o l Base Label 150 x 38mm Date: 18/04/16 Amended 10/02/17 Colecalciferol Item code: TBA TOR PRODUCT INFORMATION c a p s u l e , s o f t Excipients: Rened sunower oil, all-rac-α-Tocopherol, Gelatin, Size: 38mm x 150mm (Label Leaflet) GENERICS Glycerol, Puried Water. Each capsule provides: 2645 micrograms retinol palmitate (equivalent to 4500 IU vitamin A) and 11 capsule1 soft Retinol and micrograms colecalciferol (equivalent to 450 IU vitamin D3) Colours (label/leaflet) Non-Printed Emboss Read the package leaet before use. Colecalciferol For oral use. Swallow whole, do not chew. 4500 IU/450 IU Use as directed by your doctor. Process Process GUIDE BRAILLE This container is tted with a tamper evident top, if damaged CYAN Black Capsule, soft or missing do not use. Replace cap rmly after use. 84 Capsules Please store the capsules in the original pot. UPDATE o Do not store above 30 C. PL20491/0002 Tor Generics Ltd; DO NOT EXCEED THE STATED DAILY DOSE BN: EXP: Northwood HA6 2TH, UK Keep out of sight and reach of children. but do not remove here Peel Represents max text print area Leaflet sits here Page 2 - 140 x 38mm Page 3 - 140 x 38mm Page 4 - 140 x 38mm Page 5 - 140 x 38mm Page 6 - 140 x 38mm Page 7 - 140 x 38mm Page 8 - 140 x 38mm Package leaet: Information for the user - Keep this leaet. -

Skin-Lightening Agents: an Overview of Prescription, Office-Dispensed, and Over-The-Counter Products Chesahna Kindred, MD, MBA; Uchenna Okereke, MD; Valerie D

Review Skin-Lightening Agents: An Overview of Prescription, Office-Dispensed, and Over-the-counter Products Chesahna Kindred, MD, MBA; Uchenna Okereke, MD; Valerie D. Callender, MD Not so long ago, there was a limited number of skin-lightening agents, with hydroquinone (HQ) being the most efficacious. Currently, there are a plethora of agents, some as effective as HQ; some are avail- able over-the-counter (OTC) and others are physician dispensed. The purpose of this article is to provide physicians with an overview of available skin brighteners, including HQ, mequinol, topical retinoids, azelaic acid, arbutin and deoxyarbutin, kojic acid, licorice extract, ascorbic acid, soy, aleosin, niacinamide, and N-acetylglucosamine.COS DERM igmentation disorders can be an issue for hospital-based dermatology faculty practice revealed that all individuals, especially those with skin of dyschromia was among the 5 most common diagnoses Docolor.1,2 Although theNot natural pigmentation observed, Copy3 providing evidence that hyperpigmentation is in patients with skin of color provides many a major concern for darker-skinned racial ethnic groups. advantages such as sun protection and slowed Dermatologists and patients have a number of options Psigns of aging, it also increases susceptibility to hyper- when treating hyperpigmentation. Although some pigmentation, which can have a negative psychological patients may use prescription medications from derma- impact. A study assessing the most common diagnoses in tologists, others seek assistance from over-the-counter patients of various racial and ethnic groups treated at a (OTC) agents manufactured in the Unites States or abroad. Dermatologists face the following challenges: (1) how does one become familiar with the many OTC Dr.