Ebook Readers: User Satisfaction and Usability Issues John V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Kobo Ebook Downloads You Dont Have To

Free Kobo Ebook Downloads You Don't Have To ERROR_GETTING_IMAGES-1 Free Kobo Ebook Downloads You Don't Have To 1 / 3 2 / 3 Download Kobo Books and enjoy it on your iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch. ... Read thousands of free eBook previews or listen to audiobook samples to help you find your next ... The ONLY thing I don't like is the page turning process. ... I'm a fast reader, I can read at almost 500 words a min... if I can get to the correct page.. Download the Kobo app and browse from over 5 million free and affordable ... PLEASE NOTE: If you'd like to sync your Kobo eReader by .... If you do buy a KePub book it won't download to your PC and while it will appear on your Kobo reader (if you have the wi-fi turned on), it doesn't show up in ... FREE)” or “Adobe DRM EPUB” you are safe to buy and download as normal. ... if you make the mistake of buying a KePub ebook from Kobo (I got a .... Why don't we own the ebooks we purchase? ... Of course, if I own a Kindle or Kobo and I have downloaded content to ... They are free speech.. You can download eBooks and audioBooks directly to your tablet or smartphone using an app ... Download the OverDrive Media Console App (free) ... Sign up for an OverDrive Account (if you don't already have one, follow the prompts.. 9 sites with free Kobo books to download. Kobo Ebookstore. Free ebooks are not very well highlighted on Kobo (it's actually the problem with most ebookstores). -

Electronic Reading Devices: Are They Hurting Or Helping the Print Publishing Industry?

Electronic Reading Devices: Are They Hurting or Helping the Print Publishing Industry? by Savannah Nikkole Wesley B.A., Middle Tennessee State University, 2014 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Mass Communications Department of Mass Communications In the Graduate School Middle Tennessee State University March, 2014 DEDICATION I’d like to dedicate this paper to my son Jeremiah Eden Wesley. Jeremiah you are my inspiration and the reason I keep going and working hard to better myself. I hope that gaining my Master’s degree not only opens doors in my life, but in yours also. It is my sincerest hope that every moment spent away from you in writing this thesis only shows you how sacrifice and dedication to improving yourself can give you a brighter future. I love you my son. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank Dr. Reineke for hours of invaluable assistance during the arduous research and writing portion of this paper. Additionally I sincerely appreciate all of my committee members for taking the time to give me your insights and feedback throughout this process. Finally, I’d like to thank Howard Books for three years of invaluable work and insight into many aspects of the publishing industry, which ultimately inspired the topic of this research thesis. iii Abstract With ever-evolving and emerging technology making an impact on today’s society, examining how this technology affects mass media is essential. This study attempts to delve into an emerging media - electronic reading devices - and research how they are changing the publishing industry by looking into the arenas of newspaper, magazine, and book publishing as well as at consumers of print media on a larger scale. -

E-Books: Understanding the Basics June 2009 by Jane Lee, California Digital Library

E-books: Understanding the Basics June 2009 by Jane Lee, California Digital Library What exactly is an e-book anyway? Before we can talk about ebooks and the issues surrounding them, we must define what an e- book is. This is not as easy as one may think. Although e-books appear in headlines with regular frequency these days, there is still confusion about what exactly an e-book is that makes it difficult to focus on the real issues. For many people, especially in the last few years, an e-book is a handheld device whose main purpose is to look and act like a book. For others, an e-book is a book that one can read on one’s computer. And for a growing number of people, an e-book is something that you can read on your PDA, smartphone, iPod, etc. E-books made their first big splash on the market a decade ago, but they didn’t quite catch on with the general public. PDAs were taking a foothold, and companies began developing software that allowed people to read books on them. Subscription services for e-books – NetLibrary, for example – have been available to library patrons who have access to the required platform. The first dedicated, handheld electronic reading device, the Rocket ebook, made its appearance in 19981, but it wasn’t until the release of the Sony Reader and Amazon’s Kindle that e-book readers seemed commercially viable2. The arguments and questions about e-books – about their past, present, and future – that people formulate are shaped by how they define e-books for themselves. -

The Electronic Book As a Disruptive Technology." Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU History of the Book: Disrupting Society from Student Scholarship Tablet to Tablet 6-2015 Chapter 14 - The lecE tronic Book as a Disruptive Technology Janel Chandler Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/history_of_book Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Chandler, Janel. "The Electronic Book as a Disruptive Technology." Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet. 2015. CC BY-NC. This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of the Book: Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 14 The Electronic Book as a Disruptive Technology -Janel Chandler- In 2011, the United States made $90.3 million in the ebook market1. The electronic book, or ebook, is a book that is read on a computer or other electronic device2. Ebooks were invented in 1971 with Michael Hart’s “Project Gutenberg,” and Electronic books like the Nook and the Kindle have later took the world by storm in revolutionized the reading market1. 1998 with the invention of the ereader by Peanut Press2,3. Ebooks were originally just digital copies of books that someone typed up and put on the Internet. This new technology was a disruptive innovation because it granted instant availability, allowed for easier storage, was more convenient, and completely revolutionized the book market1. -

Compatible Ebook Devices

Current as of 5/1/2012. For the most up-to-date list, visit overdrive.com/eBookdevices. Library Compatible eBook Devices eBooks from your library’s ‘Virtual Branch’ website powered by OverDrive® are currently compatible with a variety of readers, computers and devices. eBook readers Amazon® Kindle Sony® Other devices (U.S. libraries only) • Kindle • Daily Edition • Aluratek LIBRE • Kindle 2 • Pocket Edition Air/Color/Touch • Kindle 3 • PRS-505 • En Tourage Pocket eDGe™ • Kindle DX • PRS-700 • iRiver Story HD • Kindle Touch • Touch Edition • Literati™ Reader • Kindle Keyboard • Wi-Fi PRS-T1 • Pandigital® Novel ® ™ • PocketBook Pro 602 Barnes & Noble Kobo • Skytex Primer • NOOK™ 3G+Wi-Fi • Kobo eReader The process to download • NOOK Wi-Fi • Kobo Touch or transfer eBooks to these • NOOKcolor™ devices may vary by device, most require Adobe • NOOK Touch™ Digital Editions. • NOOK Tablet Mobile devices ™ Get the FREE OverDrive Media Console app for: Other devices BlackBerry® iPad®, iPhone® & iPod touch® Android™ • Acer Iconia • Nextbook™ Next 2 ™ ® • Agasio Dropad • Pandigital Nova Windows ™ ™ Phone 7 • Archos Tablets • Samsung Galaxy Tab • ASUS® Transformer • Sony Tablet S • Coby Kyros • Sylvania Mini Tablet • Cruz™ Reader/Tablet • Toshiba Thrive™ • Dell Streak • ViewSonic gTablet • EnTourage eDGe™ • Kindle Fire ...or use the FREE Available in Mobihand™ Available in the Available in • Kobo Vox Kindle reading app on ™ SM & AppWorld App Store Android Market • Motorola® Xoom™ many of these devices. Computers Install the FREE Adobe Digital Editions software to download and read eBooks on your computer and transfer to eBook readers. Windows® XP, Vista or 7 Mac OS X v10.4.9 (or newer) OverDrive and your library are not affiliated with and do not endorse any of the devices or manufacturers listed above. -

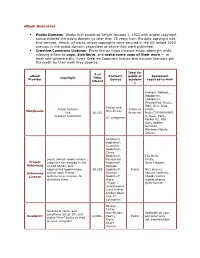

Ebook Resources Public Domain: Works First Published Before

eBook Resources Public Domain: Works first published before January 1, 1923 with proper copyright notice entered the public domain no later than 75 years from the date copyright was first secured. Hence, all works whose copyrights were secured in the US before 1923 are now in the public domain, regardless of where they were published. Creative Commons License: Every license helps creators retain copyright while allowing others to copy, distribute, and make some uses of their work — at least non-commercially. Every Creative Commons license also ensures licensors get the credit for their work they deserve. Ideal for # of eBook Content/ public or Equipment Copyright Titles Provider Genres academi required to view offered c Android, BeBook, Blackberry, eBookman, iPhone/iPod Touch, iPod, iRex, iLiad, Fiction and Public Domain Public or Kindle , Manybooks Non-Fiction and 26,021 Academic Nokia770/N800/N81 Creative Commons 0, Nook, Palm, 62 categories Pocket PC, PSP, Sony Reader, Symbian, Windows Mobile, Zaurus. Children's Bookshelf, Countries Bookshelf, Crime Bookshelf, The Nook, public domain books whose Periodicals Kindle, Project copyright has expired in the Bookshelf, Sony Ereader, Gutenberg United States, and Religion copyrighted books whose 30,000 Bookshelf, Public MP3 players, Gutenberg author gave Project Science gaming systems, License Gutenberg permission to Bookshelf, eBook readers, distribute them. Wars, mobile phones (Those 7 QiOO format. Subcategorie s are further broken down into 77 categories) Essays, Fiction, No area of terms and Non-Fiction, Readable on your conditions listed. Site just Readprint 8,000+ Poetry, Public computer only, states "Free" books to read Plays, not downloadable. on your computer. -

Die Neue Medialität Des Lesens: Ebooks Und Ebook- Reader“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die neue Medialität des Lesens: eBooks und eBook- Reader“ Verfasserin Daniela Drobna, Bakk.a phil Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im Februar 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 332 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Deutsche Philologie Betreuer: Assoz. Prof. Dr. Günther Stocker Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. Medientheoretische Einleitung ............................................................................................... 5 2.1. Definition Buch, eBook und eBook-Reader ...................................................................... 5 2.2. Medienevolution und Paradigmenwandel ....................................................................... 11 2.3. Medium und Medialität ................................................................................................... 18 2.4. Entwicklung von eBooks und eBook-Readern ............................................................... 22 2.5. Trends .............................................................................................................................. 26 3. Theorie der neuen Medialität des Lesens ............................................................................. 31 3.1. Paratexte .......................................................................................................................... 32 3.1.1. Typotopographie -

How to Cure Windows 10'S Worst Headaches These Tips and Tricks Can Help You Overcome Windows 10'S Niggling Hassles

How to cure Windows 10's worst headaches These tips and tricks can help you overcome Windows 10's niggling hassles. Ian Paul | @ianpaul Contributor, PCWorld Aug 26, 2015 3:30 AM After the Windows 8 disaster, upgrading to Windows 10 is almost palpably refreshing. Microsoft’s new operating system brings back PC-focused features it should never have lost and adds some helpful new integrations with Microsoft services. It’s not perfect, though. Despite the many highlights of Windows 10—Cortana, virtual desktops, windowed Windows Store apps, the revamped Start menu, DirectX 12, among others—there are still some annoyances with the new operating system. Windows 10 can reset your default browser if you upgrade; updates are now mandatory; and behind the scenes, the new OS is a file-sharing machine. Those are just a few of Windows 10’s notable headaches, but the good news is there are fixes for all these problems. Even better? Most are really easy to implement. Let’s dig in. Tame Windows 10’s forced updates Windows 10 home users are now pretty much required to accept and install updates at the time and choosing of Microsoft. This can be disastrous if you get a bad update that bricks your system or puts it in an endless reboot cycle, or if you have to download updates on a metered connection. Luckily, there are solutions for both. For the latter, all you have to do is set your Wi-Fi connection to metered—though note that Microsoft does not allow you to set ethernet connections as metered. -

Are E-Books Effective Tools for Learning? Reading Speed and Comprehension: Ipad®I Vs

South African Journal of Education, Volume 35, Number 4, November 2015 1 Art. # 1202, 14 pages, doi: 10.15700/saje.v35n4a1202 Are e-books effective tools for learning? Reading speed and comprehension: iPad®i vs. paper Suzanne Sackstein, Linda Spark and Amy Jenkins Information Systems, Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa [email protected] Recently, electronic books (e-books) have become prevalent amongst the general population, as well as students, owing to their advantages over traditional books. In South Africa, a number of schools have integrated tablets into the classroom with the promise of replacing traditional books. In order to realise the potential of e-books and their associated devices within an academic context, where reading speed and comprehension are critical for academic performance and personal growth, the effectiveness of reading from a tablet screen should be evaluated. To achieve this objective, a quasi-experimental within- subjects design was employed in order to compare the reading speed and comprehension performance of 68 students. The results of this study indicate the majority of participants read faster on an iPad, which is in contrast to previous studies that have found reading from tablets to be slower. It was also found that comprehension scores did not differ significantly between the two media. For students, these results provide evidence that tablets and e-books are suitable tools for reading and learning, and therefore, can be used for academic work. For educators, e-books can be introduced without concern that reading performance and comprehension will be hindered. -

Lectores De Documentos Electrónicos

Eloísa Monteoliva, Carlos Pérez-Ortiz y Rafael Repiso Lectores de documentos electrónicos Por Eloísa Monteoliva, Carlos Pérez-Ortiz y Rafael Repiso Resumen: Se repasa la evolu- ción histórica de los dispositivos lectores de documentos electró- nicos (EReaders), y se describen las tecnologías del llamado papel electrónico. Se analizan el Gyri- con, las pantallas electroforéti- cas y las que utilizan el principio de electrohumedecimiento. Se presenta la variedad de formatos de archivo compatibles con los distintos dispositivos, así como los problemas que generan. Se describen los principales mode- Eloísa Monteoliva-García, Carlos Pérez-Ortiz, es licen- Rafael Repiso-Caballero, los disponibles en el mercado y es licenciada en traducción ciado en traducción e inter- es licenciado en documen- sus prestaciones, y se invita a la e interpretación, especializa- pretación. Sus especialidades tación por la Universidad de reflexión sobre su uso y efectivi- da en la traducción jurídica, son la traducción de textos Granada. Becario del Grupo económica y comercial e in- científicos y técnicos, y sus EC3, ha participado en los dad, la difusión de documentos, terpretación de conferencias lenguas de trabajo el inglés proyectos In-Recs e In-Recj. Es así como sobre las expectativas en inglés, alemán y francés. y el francés. Es director del documentalista de la Escuela creadas por los e-lectores que, a Investiga la interpretación en departamento del Dpto. de Superior de Comunicación día de hoy, ya hacen posible la los servicios públicos. Es tra- Relaciones Externas de ESCO (ESCO), Granada. ductora, intérprete y profeso- desde 2004, así como traduc- lectura ágil y cómoda de docu- ra de inglés en ESCO. -

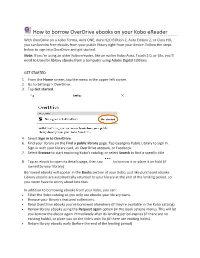

How to Borrow Overdrive Ebooks on Your Kobo Ereader

How to borrow OverDrive ebooks on your Kobo eReader With OverDrive on a Kobo Forma, Aura ONE, Aura H2O Edition 2, Aura Edition 2, or Clara HD, you can borrow free ebooks from your public library right from your device. Follow the steps below to sign into OverDrive and get started. Note: If you're using an older Kobo ereader, like an earlier Kobo Aura, Touch 2.0, or Glo, you'll need to transfer library ebooks from a computer using Adobe Digital Editions. GET STARTED 1. From the Home screen, tap the menu in the upper-left corner. 2. Go to Settings > OverDrive. 3. Tap Get started. 4. Select Sign in to OverDrive. 6. Find your library on the Find a public library page. Tap Georgina Public Library to sign in. Sign in with your library card, an OverDrive account, or Facebook. 7. Select Browse to start exploring Kobo's catalog, or select Search to find a specific title. 8. Tap an ebook to open its details page, then tap to borrow it or place it on hold (if owned by your library). Borrowed ebooks will appear in the Books section of your Kobo, just like purchased ebooks. Library ebooks are automatically returned to your library at the end of the lending period, so you never have to worry about late fees. In addition to borrowing ebooks from your Kobo, you can: Filter the Kobo catalog so you only see ebooks your library owns. Browse your library's featured collections. Read OverDrive ebooks you've borrowed elsewhere (if they're available in the Kobo catalog). -

The Evolution and Future of E-Books: a Major Shift in Technology

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Fall 11-2-2011 The volutE ion and Future of E-Books: A Major Shift nI Technology Sean F. O'Connor Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Fitzpatrick O'Connor Mr. Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation O'Connor, Sean F. and O'Connor, Fitzpatrick Mr., "The vE olution and Future of E-Books: A Major Shift nI Technology" (2011). Research Papers. Paper 184. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/184 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION AND FUTURE OF E-BOOKS: A MAJOR SHIFT IN TECHNOLOGY by Sean F. O’Connor BA, Carthage College, 2009 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts In the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale November 2011 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL THE EVOLUTION AND FUTURE OF E-BOOKS: A MAJOR SHIFT IN TECHNOLOGY By Sean F. O’Connor A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: Dr. Paul Torre, Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale 11-2-1 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Sean F.