Distribution and Economic Importance K.Evansandf.A.Rowe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOURNAL of NEMATOLOGY Description of Heterodera

JOURNAL OF NEMATOLOGY Article | DOI: 10.21307/jofnem-2020-097 e2020-97 | Vol. 52 Description of Heterodera microulae sp. n. (Nematoda: Heteroderinae) from China a new cyst nematode in the Goettingiana group Wenhao Li1, Huixia Li1,*, Chunhui Ni1, Deliang Peng2, Yonggang Liu3, Ning Luo1 and Abstract 1 Xuefen Xu A new cyst-forming nematode, Heterodera microulae sp. n., was 1College of Plant Protection, Gansu isolated from the roots and rhizosphere soil of Microula sikkimensis Agricultural University/Biocontrol in China. Morphologically, the new species is characterized by Engineering Laboratory of Crop lemon-shaped body with an extruded neck and obtuse vulval cone. Diseases and Pests of Gansu The vulval cone of the new species appeared to be ambifenestrate Province, Lanzhou, 730070, without bullae and a weak underbridge. The second-stage juveniles Gansu Province, China. have a longer body length with four lateral lines, strong stylets with rounded and flat stylet knobs, tail with a comparatively longer hyaline 2 State Key Laboratory for Biology area, and a sharp terminus. The phylogenetic analyses based on of Plant Diseases and Insect ITS-rDNA, D2-D3 of 28S rDNA, and COI sequences revealed that the Pests, Institute of Plant Protection, new species formed a separate clade from other Heterodera species Chinese Academy of Agricultural in Goettingiana group, which further support the unique status of Sciences, Beijing, 100193, China. H. microulae sp. n. Therefore, it is described herein as a new species 3Institute of Plant Protection, Gansu of genus Heterodera; additionally, the present study provided the first Academy of Agricultural Sciences, record of Goettingiana group in Gansu Province, China. -

Abacca Mosaic Virus

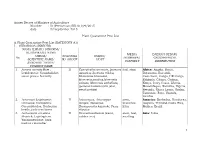

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Universidade Federal Do Ceará Centro De Ciências Agrárias Departamento De Fitotecnia Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Agronomia/Fitotecnia

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS AGRÁRIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE FITOTECNIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM AGRONOMIA/FITOTECNIA FRANCISCO BRUNO DA SILVA CAFÉ ASPECTOS BIOLÓGICOS DO NEMATOIDE DO CISTO DAS CACTÁCEAS, Cactodera cacti, EM PITAIA FORTALEZA 2019 FRANCISCO BRUNO DA SILVA CAFÉ ASPECTOS BIOLÓGICOS DO NEMATOIDE DO CISTO DAS CACTÁCEAS, Cactodera cacti, EM PITAIA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Agronomia/Fitotecnia da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Agronomia/Fitotecnia. Área de concentração: Fitossanidade. Orientadora: Profª. Dra. Carmem Dolores Gonzaga Santos . FORTALEZA 2019 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação Universidade Federal do Ceará Biblioteca Universitária Gerada automaticamente pelo módulo Catalog, mediante os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) C132a Café, Francisco Bruno da Silva. Aspectos biológicos do nematoide do cisto das cactáceas, Cactodera cacti, em pitaia / Francisco Bruno da Silva Café. – 2019. 84 f. : il. color. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Centro de Ciências Agrárias, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Agronomia (Fitotecnia), Fortaleza, 2019. Orientação: Profa. Dra. Carmem Dolores Gonzaga Santos. 1. Heteroderidae. 2. Fitonematoides. 3. Hylocereus. I. Título. CDD 630 FRANCISCO BRUNO DA SILVA CAFÉ ASPECTOS BIOLÓGICOS DO NEMATOIDE DO CISTO DAS CACTÁCEAS, Cactodera cacti, EM PITAIA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Agronomia/Fitotecnia da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Agronomia/Fitotecnia. Área de concentração: Fitossanidade. Aprovada em: ___/___/______. BANCA EXAMINADORA ___________________________________________________ Profª. Dra. Carmem Dolores Gonzaga Santos (Orientadora) Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Dr. Dagoberto Saunders de Oliveira Agência de Defesa Agropecuária do Estado do Ceará (ADAGRI) ________________________________________ Dr. -

Proteomic Responses of Uninfected Tissues of Pea Plants Infected by Root-Knot Nematode, Fusarium and Downy Mildew Pathogens Al-S

PROTEOMIC RESPONSES OF UNINFECTED TISSUES OF PEA PLANTS INFECTED BY ROOT-KNOT NEMATODE, FUSARIUM AND DOWNY MILDEW PATHOGENS AL-SADEK MOHAMED SALEM GHAZALA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Applied Sciences, University of the West of England, Bristol. December 2012 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. Al-Sadek Mohamed Salem Ghazala December 2012 Abstract Peas suffer from several diseases, and there is a need for accurate, rapid in-field diagnosis. This study used proteomics to investigate the response of pea plants to infection by the root knot nematode Meloidogyne hapla, the root rot fungus Fusarium solani and the downy mildew oomycete Peronospora viciae, and to identify potential biomarkers for diagnostic kits. A key step was to develop suitable protein extraction methods. For roots, the Amey method (Chuisseu Wandji et al., 2007), was chosen as the best method. The protein content of roots from plants with shoot infections by P. viciae was less than from non-infected plants. Specific proteins that had decreased in abundance were (1->3)-beta-glucanase, alcohol dehydrogenase 1, isoflavone reductase, malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit alpha, eukaryotic translation inhibition factor, and superoxide dismutase. No proteins increased in abundance in the roots of infected plants. For extraction of proteins from leaves, the Giavalisco method (Giavalisco et al., 2003) was best. The amount of protein in pea leaves decreased by age, and also following root infection by F. -

Plant-Parasitic Nematodes and Their Management: a Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X (Online) Vol.8, No.1, 2018 Plant-Parasitic Nematodes and Their Management: A Review Misgana Mitiku Department of Plant Pathology, Southern Agricultural Research Institute, Jinka, Agricultural Research Center, Jinka, Ethiopia Abstract Nowhere will the need to sustainably increase agricultural productivity in line with increasing demand be more pertinent than in resource poor areas of the world, especially Africa, where populations are most rapidly expanding. Although a 35% population increase is projected by 2050. Significant improvements are consequently necessary in terms of resource use efficiency. In moving crop yields towards an efficiency frontier, optimal pest and disease management will be essential, especially as the proportional production of some commodities steadily shifts. With this in mind, it is essential that the full spectrums of crop production limitations are considered appropriately, including the often overlooked nematode constraints about half of all nematode species are marine nematodes, 25% are free-living, soil inhabiting nematodes, I5% are animal and human parasites and l0% are plant parasites. Today, even with modern technology, 5-l0% of crop production is lost due to nematodes in developed countries. So, the aim of this work was to review some agricultural nematodes genera, species they contain and their management methods. In this review work the species, feeding habit, morphology, host and symptoms they show on the effected plant and management of eleven nematode genera was reviewed. -

Management Strategies for Control of Soybean Cyst Nematode and Their Effect on Nematode Community

Management Strategies for Control of Soybean Cyst Nematode and Their Effect on Nematode Community A Thesis SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Zane Grabau IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Dr. Senyu Chen June 2013 © Zane Grabau 2013 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my committee members John Lamb, Robert Blanchette, and advisor Senyu Chen for their helpful feedback and input on my research and thesis. Additionally, I would like to thank my advisor Senyu Chen for giving me the opportunity to conduct research on nematodes and, in many ways, for making the research possible. Additionally, technicians Cathy Johnson and Wayne Gottschalk at the Southern Research and Outreach Center (SROC) at Waseca deserve much credit for the hours of technical work they devoted to these experiments without which they would not be possible. I thank Yong Bao for his patient in initially helping to train me to identify free-living nematodes and his assistance during the first year of the field project. Similarly, I thank Eyob Kidane, who, along with Senyu Chen, trained me in the methods for identification of fungal parasites of nematodes. Jeff Vetsch from SROC deserves credit for helping set up the field project and advising on all things dealing with fertilizers and soil nutrients. I want to acknowledge a number of people for helping acquire the amendments for the greenhouse study: Russ Gesch of ARS in Morris, MN; SROC swine unit; and Don Wyse of the University of Minnesota. Thanks to the University of Minnesota Plant Disease Clinic for contributing information for the literature review. -

Root-Parasitic Nematodes of Rice

Articlebibliographique ROOT-PARASITIC NEMATODES OF RICE Renaud FORTUNERand Georges MERNY ORSTOM, Laboratoire de Nématologie, B.P. TT 51, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire and ORSTOM, Laboratoire de Biologie des Sols, 70-74 route d’Aulnay, 93140 Bondy, France Geographicaldistribution of nematodes Hirschmanniella of which several species have associated with rice been observed associated with rice. H. oryzae is the most frequently encountered inal1 countries whererice is grown, except Europe. Another More than one hundred species of nematodes species, H. spinicaudata, iscommon inWest have been reported from upland and paddyrice Africa andhas been observed once inSouth in many countries (Tab. 1).Their frequency and America. In WestAfrica a geographical gradient importance are very variable and, in mostcases is observed in the distribution of both species : the existence of a parasitic relationship withrice H. spinicaudata is highly prevalent in the humid is probable but has not been demonstrated. countries ,like Ivory Coast whereas H. oryzae is Manyspecies of rootnematodes have been foundmostly in the Sahelian regions (North observed both in dry and irrigatedfields but very Senegal) ; a balanced mixture of both species is few species are found in both situations. Several observed in intermediategeographical areas surveys made by the authors in WestAfrica have (Gambia). shown that a relatively low number of species Ten recognizedspecies of Pratylenchus have are adapted to permanently flooded conditions. been identified parasitizing rice. The most fre- When the field is only temporarily flooded, the quent is P. brachyurus, rather common in Afri- number of species present is higherand the can upland rice fields, which has been observed nematode fauna tends to ressemble that observedonce in South America ; P. -

Medit Cereal Cyst Nem Circ221

Nematology Circular No. 221 Fl. Dept. Agriculture & Cons. Svcs. November 2002 Division of Plant Industry The Mediterranean Cereal Cyst Nematode, Heterodera latipons: a Menace to Cool Season Cereals of the United States1 N. Greco2, N. Vovlas2, A. Troccoli2 and R.N. Inserra3 INTRODUCTION: Cool season cereals, such as hard and bread wheat, oats and barley, are among the major staple crops of economic importance worldwide. These monocots are parasitized by many pathogens and pests including plant parasitic nematodes. Among nematodes, cyst-forming nematodes (Heterodera spp.) are considered to be very damaging because of crop losses they induce and their worldwide distribution. The most economically important cereal cyst nematode species damaging winter cereals are: Heterodera avenae Wollenweber, which occurs in the United States and is the most widespread and damaging on a world basis; H. filipjevi (Madzhidov) Stelter, found in Europe and Mediterranean areas and most often confused with H. avenae; and H. hordecalis Andersson, which seems to be confined to central and north European countries. In the 1950s and early 1960s, a cyst nematode was detected in the Mediterranean region (Israel and Libya) on the roots of stunted wheat plants (Fig. 1 A,B). It was described as a new species and named H. latipons based on morphological characteristics of the Israel population (Franklin 1969). Subsequently, damage by H. latipons was reported on cereals in other Mediterranean countries (Fig. 1). MORPHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND DIAGNOSIS: Heterodera latipons cysts are typically ovoid to lemon-shaped as those of H. avenae. They belong to the H. avenae group be- cause they have short vulva slits (< 16 µm) (Figs. -

JOURNAL of NEMATOLOGY Morphological And

JOURNAL OF NEMATOLOGY Article | DOI: 10.21307/jofnem-2020-098 e2020-98 | Vol. 52 Morphological and molecular characterization of Heterodera dunensis n. sp. (Nematoda: Heteroderidae) from Gran Canaria, Canary Islands Phougeishangbam Rolish Singh1,2,*, Gerrit Karssen1, 2, Marjolein Couvreur1 and Wim Bert1 Abstract 1Nematology Research Unit, Heterodera dunensis n. sp. from the coastal dunes of Gran Canaria, Department of Biology, Ghent Canary Islands, is described. This new species belongs to the University, K.L. Ledeganckstraat Schachtii group of Heterodera with ambifenestrate fenestration, 35, 9000, Ghent, Belgium. presence of prominent bullae, and a strong underbridge of cysts. It is characterized by vermiform second-stage juveniles having a slightly 2National Plant Protection offset, dome-shaped labial region with three annuli, four lateral lines, Organization, Wageningen a relatively long stylet (27-31 µm), short tail (35-45 µm), and 46 to 51% Nematode Collection, P.O. Box of tail as hyaline portion. Males were not found in the type population. 9102, 6700, HC, Wageningen, Phylogenetic trees inferred from D2-D3 of 28S, partial ITS, and 18S The Netherlands. of ribosomal DNA and COI of mitochondrial DNA sequences indicate *E-mail: PhougeishangbamRolish. a position in the ‘Schachtii clade’. [email protected] This paper was edited by Keywords Zafar Ahmad Handoo. 18S, 28S, Canary Islands, COI, Cyst nematode, ITS, Gran Canaria, Heterodera dunensis, Plant-parasitic nematodes, Schachtii, Received for publication Systematics, Taxonomy. September -

"Structure, Function and Evolution of the Nematode Genome"

Structure, Function and Advanced article Evolution of The Article Contents . Introduction Nematode Genome . Main Text Online posting date: 15th February 2013 Christian Ro¨delsperger, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Adrian Streit, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Ralf J Sommer, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany In the past few years, an increasing number of draft gen- numerous variations. In some instances, multiple alter- ome sequences of multiple free-living and parasitic native forms for particular developmental stages exist, nematodes have been published. Although nematode most notably dauer juveniles, an alternative third juvenile genomes vary in size within an order of magnitude, com- stage capable of surviving long periods of starvation and other adverse conditions. Some or all stages can be para- pared with mammalian genomes, they are all very small. sitic (Anderson, 2000; Community; Eckert et al., 2005; Nevertheless, nematodes possess only marginally fewer Riddle et al., 1997). The minimal generation times and the genes than mammals do. Nematode genomes are very life expectancies vary greatly among nematodes and range compact and therefore form a highly attractive system for from a few days to several years. comparative studies of genome structure and evolution. Among the nematodes, numerous parasites of plants and Strikingly, approximately one-third of the genes in every animals, including man are of great medical and economic sequenced nematode genome has no recognisable importance (Lee, 2002). From phylogenetic analyses, it can homologues outside their genus. One observes high rates be concluded that parasitic life styles evolved at least seven of gene losses and gains, among them numerous examples times independently within the nematodes (four times with of gene acquisition by horizontal gene transfer. -

DNA Barcoding Evidence for the North American Presence of Alfalfa Cyst Nematode, Heterodera Medicaginis Tom Powers

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Plant Pathology Plant Pathology Department 8-4-2018 DNA barcoding evidence for the North American presence of alfalfa cyst nematode, Heterodera medicaginis Tom Powers Andrea Skantar Timothy Harris Rebecca Higgins Peter Mullin See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/plantpathpapers Part of the Other Plant Sciences Commons, Plant Biology Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant Pathology Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Plant Pathology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Tom Powers, Andrea Skantar, Timothy Harris, Rebecca Higgins, Peter Mullin, Saad Hafez, Zafar Handoo, Tim Todd, and Kirsten S. Powers JOURNAL OF NEMATOLOGY Article | DOI: 10.21307/jofnem-2019-016 e2019-16 | Vol. 51 DNA barcoding evidence for the North American presence of alfalfa cyst nematode, Heterodera medicaginis Thomas Powers1,*, Andrea Skantar2, Tim Harris1, Rebecca Higgins1, Peter Mullin1, Saad Hafez3, Abstract 2 4 Zafar Handoo , Tim Todd & Specimens of Heterodera have been collected from alfalfa fields 1 Kirsten Powers in Kearny County, Kansas and Carbon County, Montana. DNA 1University of Nebraska-Lincoln, barcoding with the COI mitochondrial gene indicate that the species is Lincoln NE 68583-0722. not Heterodera glycines, soybean cyst nematode, H. schachtii, sugar beet cyst nematode, or H. trifolii, clover cyst nematode. Maximum 2 Mycology and Nematology Genetic likelihood phylogenetic trees show that the alfalfa specimens form a Diversity and Biology Laboratory sister clade most closely related to H. -

Inventory and Review of Quantitative Models for Spread of Plant Pests for Use in Pest Risk Assessment for the EU Territory1

EFSA supporting publication 2015:EN-795 EXTERNAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT Inventory and review of quantitative models for spread of plant pests for use in pest risk assessment for the EU territory1 NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology 2 Maclean Building, Benson Lane, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford, OX10 8BB, UK ABSTRACT This report considers the prospects for increasing the use of quantitative models for plant pest spread and dispersal in EFSA Plant Health risk assessments. The agreed major aims were to provide an overview of current modelling approaches and their strengths and weaknesses for risk assessment, and to develop and test a system for risk assessors to select appropriate models for application. First, we conducted an extensive literature review, based on protocols developed for systematic reviews. The review located 468 models for plant pest spread and dispersal and these were entered into a searchable and secure Electronic Model Inventory database. A cluster analysis on how these models were formulated allowed us to identify eight distinct major modelling strategies that were differentiated by the types of pests they were used for and the ways in which they were parameterised and analysed. These strategies varied in their strengths and weaknesses, meaning that no single approach was the most useful for all elements of risk assessment. Therefore we developed a Decision Support Scheme (DSS) to guide model selection. The DSS identifies the most appropriate strategies by weighing up the goals of risk assessment and constraints imposed by lack of data or expertise. Searching and filtering the Electronic Model Inventory then allows the assessor to locate specific models within those strategies that can be applied.