25 the Land Capability Classification of Sabah Volume 4 the Interior Residency and Labuan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil, Gas & Energy Sector

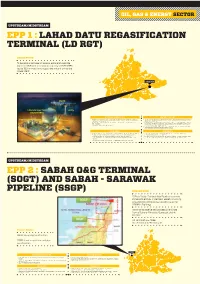

OIL, GAS & ENERGY SECTOR UPSTREAM/MIDSTREAM EPP 1 : LAHAD DATU REGASIFICATION TERMINAL (LD RGT) DESCRIPTION To develop a facilities to receive, store and vaporize imported LNG with a maximum capacity of 0.76 MTPA (up to 100 mmscfd) and supply the natural gas to the Power Plant lahad datu Berth LNG Storage Tank Jetty (0.76 MTPA) Key outcomes of the EPP / KPIs What needs to be done? Vaporization Station • Availability of natural gas supply at east coast of Sabah including Sandakan, Lahad Datu • Construction period of LNG Storage Tank which is the critical path of the project (normally and Tawau (also along the route) will take up to 24 months) • Transfer of technology and knowledge to local manpower and contractors who are involved • Front End phase of a project, where activities are mainly focused towards project planning with this project and contracting/bidding activities for the appointment of Frond End Engineering Design • Spurring the economy along the pipeline Consultant expected in mid-October 2011 • Evaluate and finalize the land lease of the reclaimed land of the proposed site with POIC. • Site Reclamation works is expected to start by Q1 2012 Key Challenges Mitigation Plan • Transporting major equipment and bulk materials from Sandakan to Lahad Datu (~200km) • Improvement of the road condition from Sandakan to Lahad Datu or consider for • Shortage of capable manpower due to simultaneous construction of LD power plant permanent/temporary jetty at Lahad Datu • Available manpower are lack of re-gas terminal construction skills (special) -

09 Lim Index.Indd 142 5/16/08 3:10:49 PM Index 143

INDEX 1982 Federal election, 82 Anwar Ibrahim, 66, 69, 109 1994 Sabah State elections, 81 Anti-Corruption Agency, 62 Asek bin Pintar, 96 A Assistant Residents, 21 ABC system, 84–86, 99–100, 120 Association for the Relief of A. G. Sahari, Datuk Haji, 106 Calamity, 36 Abell, Anthony (Sir), 57 Abdilah Hassan, 80 B Abdul Rahman (Tunku), see Tunku Bajau, 16 Abdul Rahman hostility with Kadazan-Dusun Abdul Razak (Tun), see Tun Abdul communities, 18 Razak Bank Islam Malaysia, 69 Aceh, 12 Bank Kerjasama Rakyat, 62 Adat rituals, 113 Banten, 12 Administration of Muslim Law Barisan Nasional, 1, 6, 53 Enactment, 109 constitutional amendments, 54 Advisory Council for Native Affairs expulsion of USNO from, 77–78 (ACNA), 31 Basel Church, 30 membership, 32, 34 BERJAYA administration, 63, 68 Affendi Stephen, Haji, 80 developmentalist approach to Ahmad Raffae, Pangiran Haji, 50 Islamization, 122 Alcock, Rutherford (Sir), 20, 39 economic transformation under, Aliuddin, A.K., 63 82–86 Amanah Saham Nasional, 120 failing to live up to multiracial Amanah Saham Rakyat Sabah, 89, pledges, 122 99 financial allocation for Islamic Amanah Saham Rakyat, 89 activities, 107 Amanah Saham Tun Hj Datu Islamization drive, 120 Mustapha, 88 political economy, 84–86 Angkatan Belia Islam (ABIM), 69 setting up of training courses, 94 142 09 Lim Index.indd 142 5/16/08 3:10:49 PM Index 143 BERJAYA Corporate Governance C institutional expansion of, Chartered Company Territory, 39 87–89 China BERJAYA party, 7, 56 education curriculum, 30 1981 State Elections, 78 China Borneo Company, -

Sabah REDD+ Roadmap Is a Guidance to Press Forward the REDD+ Implementation in the State, in Line with the National Development

Study on Economics of River Basin Management for Sustainable Development on Biodiversity and Ecosystems Conservation in Sabah (SDBEC) Final Report Contents P The roject for Develop for roject Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background of the Study .............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Study ................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Detailed Work Plan ...................................................................................................... 1 ing 1.4 Implementation Schedule ............................................................................................. 3 Inclusive 1.5 Expected Outputs ......................................................................................................... 4 Government for for Government Chapter 2 Rural Development and poverty in Sabah ........................................................... 5 2.1 Poverty in Sabah and Malaysia .................................................................................... 5 2.2 Policy and Institution for Rural Development and Poverty Eradication in Sabah ............................................................................................................................ 7 2.3 Issues in the Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation from Perspective of Bangladesh in Corporation City Biodiversity -

“Fractured Basement” Play in the Sabah Basin? – the Crocker and Kudat Formations As Hydrocarbon Reservoirs and Their Risk Factors Mazlan Madon1,*, Franz L

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Malaysia, Volume 69, May 2020, pp. 157 - 171 DOI: https://doi.org/10.7186/bgsm69202014 “Fractured basement” play in the Sabah Basin? – the Crocker and Kudat formations as hydrocarbon reservoirs and their risk factors Mazlan Madon1,*, Franz L. Kessler2, John Jong3, Mohd Khairil Azrafy Amin4 1 Advisor, Malaysian Continental Shelf Project, National Security Council, Malaysia 2 Goldbach Geoconsultants O&G and Lithium Exploration, Germany 3 A26-05, One Residences, 6 Jalan Satu, Chan Sow Lin, KL, Malaysia 4 Malaysia Petroleum Management, PETRONAS, Malaysia * Corresponding author email address: [email protected] Abstract: Exploration activities in the Sabah Basin, offshore western Sabah, had increased tremendously since the discovery of oil and gas fields in the deepwater area during the early 2000s. However, the discovery rates in the shelfal area have decreased over the years, indicating that the Inboard Belt of the Sabah Basin may be approaching exploration maturity. Thus, investigation of new play concepts is needed to spur new exploration activity on the Sabah shelf. The sedimentary formations below the Deep Regional Unconformity in the Sabah Basin are generally considered part of the economic basement which is seismically opaque in seismic sections. Stratigraphically, they are assigned to the offshore Sabah “Stages” I, II, and III which are believed to be the lateral equivalents of the pre-Middle Miocene clastic formations outcropping in western Sabah, such as the Crocker and Kudat formations and some surface hydrocarbon seeps have been reported from Klias and Kudat peninsulas. A number of wells in the inboard area have found hydrocarbons, indicating that these rocks are viable drilling targets if the charge and trapping mechanisms are properly understood. -

Landslide Factors and Susceptibility Mapping on Natural and Artificial

Sains Malaysiana 46(9)(2017): 1531–1540 http://dx.doi.org/10.17576/jsm-2017-4609-23 Landslide Factors and Susceptibility Mapping on Natural and Artificial Slopes in Kundasang, Sabah (Faktor Tanah Runtuh dan Pemetaan Kerentanan ke atas Cerun Semula Jadi dan Buatan di Kundasang, Sabah) KAMILIA SHARIR, RODEANO ROSLEE, LEE KHAI ERN & NORBERT SIMON* ABSTRACT This study was carried out on the hilly topographic area in Kundasang, Sabah. This area is known to be extremely prone to landslides that occurred either naturally or by human interference to natural slopes. Aerial photographs interpretation was conducted in order to identify landslide distributions across three assessment years (2012, 2009 and 1984). These datasets were classified into two landslides groups based on their occurrences; natural and artificial. A total of 362 naturally occurring landslides were identified and another 133 are artificial slope landslides. Physical parameters which include lithology, slope angle, slope aspect and soil series were analyzed with each landslide group to examine the different influence of these parameters on each of the group. From the analysis, the landslide density for the natural landslide group shows that more than 35° slope angle and slope aspect facing east and southwest are prone to landslides. In terms of geological materials, high landslide density is recorded in the phyllite, shale, siltstone and sandstone lithologies group and the Pinosuk, Kepayan and Trusmadi soil series. In contrast, for the artificial slope landslide, high landslide density is observed in the 25°-35° slope angle and similar density in every slope aspect classes. The geological materials however have similar landslide density across their factors’ classes. -

Day 1: KOTA KINABALU –APIN-APIN, KENINGAU- PAGANDADAN

Standard Itinerary Day 1: KOTA KINABALU –APIN-APIN, KENINGAU- PAGANDADAN RANGERS (Dinner) Meet your driver in the designated hotel and then will transfer to Kapayan Recreation Resources(KRR) where all climbers will gather before proceed to the starting point in Apin- Apin, Keningau. Upon arrival to Apin-Apin Keningau, continue to register and double check the climbing permit and attend to a short safety briefing before start heading to the starting point base camp lead by the mountain guide. Estimated time taken shall be around 3- 4 hours depends on your pace. Along the way, stop by at the captivating Trusmadi Waterfall. Dinner will be served at the camp site and later overnight stay at the camp. After dinner, join in with a short night walk in search of nocturnal animal before proceed to rest in the tent provided. (Timing and places all depend on your schedule of arrival) Day 2: CAMPSITE – WATERFALL VISIT (Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner) Wake up around 06:00 hrs to prepare for a trek to the Kalawot Waterfall. The trek shall takes around 1 hour to 1 hour 30 minutes to arrive. Upon arrival, relax and enjoy the water. Later on, trek back to the base camp and proceed for lunch upon arrival to the camp site. Listen to a short briefing before heading to bed from the Leader Guide. Rest early for the night as you will be require to wake up early for the climb to the summit later on. Day 3: BASE CAMP - SUMMIT- PAGANDADAN RANGERS- KOTA KINABALU (Breakfast, Lunch) Wake up as early as 00:00 hrs to get ready for another 4-5 hours track. -

25 the Land Capability Classification of Sabah Volume 1 the Tawau Residency

25 The land capability classification of Sabah Volume 1 The Tawau Residency OdEXäxo] ßte©@x>a?®^ ®(^ Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued information available for consultation, following Fair Use Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the originators. For questions please contact [email protected] indicating the item reference number concerned. The land capability classification of Sabah Volume 1 The Tawau Residency T-i2>S Land Resources Division The land capability classification of Sabah Volume 1 The Tawau Residency (with an Introduction and Summary for Volumes 1—4) P Thomas, F K C Lo and A J Hepburn Land Resource Study 25 Land Resources Division, Ministry of Overseas Development Tolworth Tower, Surbiton, Surrey, England KT6 7DY 1976 THE LAND RESOURCES DIVISION The Land Resources Division of the Ministry of Overseas Development assists develop ing countries in mapping, investigating and assessing land resources, and makes recommendations on the use of these resources for the development of agriculture, livestock husbandry and forestry; it also gives advice on related subjects to overseas governments and organisations, makes scientific personnel available for appointment abroad and provides lectures and training courses in the basic techniques of resource appraisal. The Division works in close cooperation with government departments, research institutes, universities and international organisations concerned with land resource assessment and development planning. -

Supernatural Elements in Tangon and Their Connection with Ethnic Ranau Dusun Beliefs

SUPERNATURAL ELEMENTS IN TANGON AND THEIR CONNECTION WITH ETHNIC RANAU DUSUN BELIEFS (Unsur-unsur Keajaiban dalam Tangon dan Perkaitannya dengan Konteks Kepercayaan Etnik Dusun di Ranau) Steefi Yalim [email protected] *Low Kok On [email protected] Faculty of Humanities, Arts & Heritage, University Malaysia Sabah. Published online: 5 December 2019 To Cite: Steefi Yalim and Low Kok On. (2019). Supernatural Elements in Tangon and Their Connection with Ethnic Ranau Dusun Beliefs. Malay Literature, 32(2), 185-206. Abstract Storytelling (monusui) is an oral tradition handed down from generation to generation among the Dusun ethnic group in Sabah. In the past, the narration of tangon (folktales) was a form of entertainment and an informal medium of education for the Dusun ethnic. A total of 44 tangon were successfully collected during fieldworks conducted in the state of Ranau. On examining the 44 tangon, 13 were found to be stories that contain supernatural elements or elements of magic. Among these are phenomena such as “humans being resurrected”, “humans giving birth to animals”, “humans morphing into birds”, and many more. These elements in tangon are the result of its creator’s imagination and creativity. The issue here is that if these elements are not analysed and highlighted, we will not be able to comprehend the imagination, creativity, and beliefs of the previous generations. The result of the analysis by way of interpretation of these supernatural elements in tangon shows that the Ranau Dusun ethnic group had a rich imagination and a great deal of creativity in conceiving these © Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. 2019. -

Curriculum Vite

BIODATA Ejria Binti Saleh Senior Lecturer, Borneo Marine Research Institute, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia BIO SUMMARY - LIM AI YIM - MALAYSIA CURRICULUM VITE PERSONAL INFORMATION Name Name of Current Employer: Borneo Marine Research Institute Ejria Binti Saleh Universiti Malaysia Sabah Corresponding Address: E-mail: Borneo Marine Research Institute, [email protected]/[email protected] Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88999 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Malaysia Tel: 6088-320000 ext: 2594 Fax: 6088-320261 NRIC: 710201-12-5042 Nationality: Malaysian Date of Birth: 01 January 1971 Sex: Female ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION Diploma/Degree Name of University Year Major Doctor of Philosophy Universiti Malaysia 2007 Physical Oceanography Sabah, Malaysia. Master Science University of Liverpool, 1997 Recent Environmental United Kingdom. Change Bachelor of Fisheries Universiti Putra 1996 Marine science Sc. (Marine Sciences) Malaysia, Malaysia. 1 Diploma in Fisheries Universiti Putra 1993 Fisheries Malaysia, Malaysia. RESEARCH PROJECTS Project Project Title Role Year Funder Status No. B-08-0- Tidal effects on salinity Co- 2002-2003 FRGS Completed 12ER intrusion and suspended Researcher sediment discharged in Manggatal River Estuary, Sabah SCF0019- Study of the factors regulating Co- 2006 -2009 Science Completed AGR-2006 the bloom mechanisms of Researcher Fund harmful algal species in Sabah SCF0015- Coastal processes and Co- 2006 -2009 Science Completed ENV-2006 geomorphologic Researcher Fund characteristics of major coastal towns in East Sabah for assessment -

Evaluation of the Pl 480 Title Ii Program Country Report

EVALUATION OF THE PL 480 TITLE II PROGRAM COUNTRY REPORT: MALAYSIA Submitted to the U. S. Agency for International Development Washington, D. C. February 29, 1972 Checchi and Company 815 Connecticut Avenue, N. W. Washington, D. C. 20006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Section I Background and Setting of PL 480 Title II Programs in Malaysia 1 Section II Food for Peace in Malaysia: The Framework 5 A. Goals of Cooperating Parties 5 B. Project Purposes and Descriptions 6 Section III Title II Operations in Malaysia: Findings and Suggestions 17 A. Mother/Child Feeding and School Feeding 17 B. Economic and Community Development - Food-for-Work 20 C. Adult Institutional Feeding and Health Cases 27 Section IV Food for Peace Central Issues and Problems 29 A. Overall Program Evaluation 29 B. Program Planning and Management 29 SECTION I BACKGROUND AND SETTING OF PL 480 TITLE II PROGRAMS IN MALAYSIA This draft country Evaluation Report is an appraisal of the effec tiveness of the PL 480 Title II program in Malysia. It has been prepared for two purposes: (1) to provide descriptive and analytical material for the worldwide evaluation of Title II being conducted by Checchi and Com pany for the Agency for International Development; and (2) to provide the U. S. Embassy in Malaysia with the Evaluation Team's observations, findings and suggestions resulting from our three week visit to the country. The study is concerned with programming and management matters, and seeks to determine whether the best attainable results are being achieved through ultilization of Title II foods. Auditing matters are of concern only where they affect program implementation. -

Conservation Area Management Plan

FMU10: CAMP VER. 2 1. SITE CONSERVATION CONTEXT OF FOREST MANAGEMENT UNIT (FMU 10) 1.1 Objective of the FMU10: CAMP Ver. 2 Under the mid – term review as documented under the Revised Conservation Area Management Plan (CAMP) for FMU 10, which was approved by the Chief Conservator of Forests Sabah (formerly the Director of Forestry) in the year 2013, a new set of CAMP has to be prepared by the Management Planning Core Team (MPCT) including the Resource Persons Group (RPG) for FMU10 towards the end of 2016. This new document, also known as the Second Revised CAMP for FMU10, is referred to as FMU10: CAMP Ver. 2 (FMU10: CAMP Version 2). The rationale and management objectives of FMU10: CAMP Ver. 2 is as follows: 1.1.1 Area, Site’s Name and Location: The whole of the FMU 10 (Tambunan) is located in central Sabah, between longitude E 116o 21’ 13. 8” and E 117o 01’ and latitude N 5o 27’N and 5o 52’N. For management and identification purposes under this FMU10: CAMP Ver. 2, the area and the site’s name is known as the Forest Management Unit Number 10 or FMU10 (Tambunan). As of December 2016, the FMU10 consisted of the Nuluhon Trusmadi Forest Reserve with a total size of 74, 736 hectare (ha) and the Sg. Kiluyu Forest Reserve with a total area of 1, 068 ha. Both are Class 1 (Protection) Forest Reserves, with a total size of 75,804 ha. In late 2016, an area totalling 12,241 ha was excised out from the neighbouring Trusmadi Forest Reserve (FMU 5: Class II Forest Reserve) in Ranau. -

Sabah 90000 Tabika Kemas Kg

Bil Nama Alamat Daerah Dun Parlimen Bil. Kelas LOT 45 BATU 7 LORONG BELIANTAMAN RIMBA 1 KOMPLEKS TABIKA KEMAS TAMAN RIMBAWAN Sandakan Sungai SiBuga Libaran 11 JALAN LABUKSANDAKAN SABAH 90000 TABIKA KEMAS KG. KOBUSAKKAMPUNG KOBUSAK 2 TABIKA KEMAS KOBUSAK Penampang Kapayan Penampang 2 89507 PENAMPANG 3 TABIKA KEMAS KG AMAN JAYA (NKRA) KG AMAN JAYA 91308 SEMPORNA Semporna Senallang Semporna 1 TABIKA KEMAS KG. AMBOI WDT 09 89909 4 TABIKA KEMAS KG. AMBOI Tenom Kemabong Tenom 1 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TABIKA KEMAS KAMPUNG PULAU GAYA 88000 Putatan 5 TABIKA KEMAS KG. PULAU GAYA ( NKRA ) Tanjong Aru Putatan 2 KOTA KINABALU (Daerah Kecil) KAMPUNG KERITAN ULU PETI SURAT 1894 89008 6 TABIKA KEMAS ( NKRA ) KG KERITAN ULU Keningau Liawan Keningau 1 KENINGAU 7 TABIKA KEMAS ( NKRA ) KG MELIDANG TABIKA KEMAS KG MELIDANG 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 8 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG KUANGOH TABIKA KEMAS KG KUANGOH 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 9 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG MONGITOM JALAN APIN-APIN 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 TABIKA KEMAS KG. SINDUNGON WDT 09 89909 10 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG. SINDUNGON Tenom Kemabong Tenom 1 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TAMAN MUHIBBAH LORONG 3 LOT 75. 89008 11 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) TAMAN MUHIBBAH Keningau Liawan Keningau 1 KENINGAU 12 TABIKA KEMAS ABQORI KG TANJUNG BATU DARAT 91000 Tawau Tawau Tanjong Batu Kalabakan 1 FASA1.NO41 JALAN 1/2 PPMS AGROPOLITAN Banggi (Daerah 13 TABIKA KEMAS AGROPOLITAN Banggi Kudat 1 BANGGIPETI SURAT 89050 KUDAT SABAH 89050 Kecil) 14 TABIKA KEMAS APARTMENT INDAH JAYA BATU 4 TAMAN INDAH JAYA 90000 SANDAKAN Sandakan Elopura Sandakan 2 TABIKA KEMAS ARS LAGUD SEBRANG WDT 09 15 TABIKA KEMAS ARS (A) LAGUD SEBERANG Tenom Melalap Tenom 3 89909 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TABIKA KEMAS KG.