Rob Ninkovich, Linebacker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Patriots at Philadelphia Game Notes

GAME NOTES AFC CHAMPIONSHIP GAME New England Patriots vs. Jacksonville Jaguars – January 21, 2018 TEAM NOTES Patriots extend record to 10th Super Bowl appearance. Second time reaching back-to-back Super Bowls. Kraft becomes third owner with 30 postseason wins. PATRIOTS EXTEND NFL-RECORD TO 10TH SUPER BOWL OVERALL; NINTH OF THE KRAFT ERA New England has advanced to its 10th Super Bowl in franchise history, a total that is the most in the NFL. The Patriots appearance in Super Bowl LII will be its ninth Super Bowl appearance since Robert Kraft purchased the team in 1994, a total that is the most in the league over that span (Pittsburgh and Denver are second with four). Kraft is the first owner in NFL history to have his team in nine Super Bowls. ALL-TIME SUPER BOWL BERTHS 10 New England 8 Dallas 8 Pittsburgh 8 Denver 6 San Francisco 5 Green Bay Packers 5 New York Giants 5 Washington Redskins 5 Oakland Raiders 5 Miami Dolphins PATRIOTS IN THE SUPER BOWL (5-4) Date Game Opponent W/L Score 01/26/86 XX Chicago L 10-46 01/26/97 XXXI Green Bay L 21-35 02/03/02 XXXVI St. Louis W 20-17 02/01/04 XXXVIII Carolina W 32-29 02/06/05 XXXIX Philadelphia W 24-21 02/03/08 XLII New York Giants L 14-17 02/05/12 XLVI New York Giants L 17-21- 02/01/15 XLIX Seattle W 28-24 02/05/17 LI Atlanta W 34-28 (OT) PATRIOTS WILL NOW HAVE A CHANCE TO TIE FOR MOST SUPER BOWL WINS The Patriots will have a chance to tie Pittsburgh for the NFL lead with six Super Bowl wins in franchise history. -

The Fifth Down

Members get half off on June 2006 Vol. 44, No. 2 Outland book Inside this issue coming in fall The Football Writers Association of President’s Column America is extremely excited about the publication of 60 Years of the Outland, Page 2 which is a compilation of stories on the 59 players who have won the Outland Tro- phy since the award’s inception in 1946. Long-time FWAA member Gene Duf- Tony Barnhart and Dennis fey worked on the book for two years, in- Dodd collect awards terviewing most of the living winners, spin- ning their individual tales and recording Page 3 their thoughts on winning major-college football’s third oldest individual award. The 270-page book is expected to go on-sale this fall online at www.fwaa.com. All-America team checklist Order forms also will be included in the Football Hall of Fame, and 33 are in the 2006-07 FWAA Directory, which will be College Football Hall of Fame. Dr. Outland Pages 4-5 mailed to members in late August. also has been inducted posthumously into As part of the celebration of 60 years the prestigious Hall, raising the number to 34 “Outland Trophy Family members” to of Outland Trophy winners, FWAA mem- bers will be able to purchase the book at be so honored . half the retail price of $25.00. Seven Outland Trophy winners have Nagurski Award watch list Ever since the late Dr. John Outland been No. 1 picks overall in NFL Drafts deeded the award to the FWAA shortly over the years, while others have domi- Page 6 before his death, the Outland Trophy has nated college football and pursued greater honored the best interior linemen in col- heights in other areas upon graduation. -

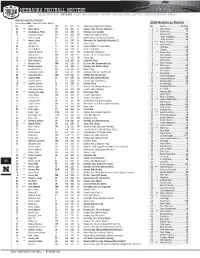

2009 Roster-Outlook.Indd

Nebraska football rosters | Coaching Staff | Outlook | Meet the Huskers | Review | Record Book | History | Administration | Media | 2009 Alphabetical Roster Lettermen in Bold; *-Indicates Letters Earned 2009 Numerical Roster No. Name Pos. Ht. Wt. Yr. Home town (High School/College) No. Name .......................... Position 95 ** Allen, Pierre DE 6-5 265 Jr. Denver, Colo. (Thomas Jefferson) 1 * Chris Brooks ...........................WR 21 ** Amukamara, Prince CB 6-1 200 Jr. Glendale, Ariz. (Apollo) 1 ** Adi Kunalic ..............................PK 70 Anderson, Kenny DE 6-2 250 RFr. Omaha, Neb. (Millard West) 2 Antonio Bell ...........................WR . 9 Ankrah, Jason DE 6-4 255 Fr. Gaithersburg, Md. (Quince Orchard) 2 Lazarri Middleton ....................DB 4 ** Asante, Larry S 6-1 215 Sr. Alexandria, Va. (Hayfield/Coffeyville CC) 3 Taylor Martinez .......................QB 3 *** Rickey Thenarse .........................S . 70 Ash, Nick OL 6-5 270 Fr. Keller, Texas 4 ** Larry Asante ...............................S 66 Barrett, Cruz OL 6-4 310 Jr. Daytona Beach, Fla. (Mainland) 4 Ty Kildow ...............................WR 91 Barry, Robert TE 6-8 220 Fr. Battle Creek, Neb. 5 Zac Lee ....................................QB 83 Bechtold, Damon TE 6-4 235 RFr. Omaha, Neb. (Westside) 5 ** Antony West ...........................CB 2 Bell, Antonio WR 6-2 180 Fr. Daytona Beach, Fla. (Mainland) 6 Khiry Cooper ..........................WR 39 Blatchford, Justin CB 6-1 195 RFr. Ponca, Neb. 7 Dejon Gomes ..........................CB 14 * Blue, Anthony CB 5-10 185 So. Cedar Hill, Texas 7 Kody Spano .............................QB 1 * Brooks, Chris WR 6-2 215 Sr. St. Louis, Mo. (Hazelwood East) 8 Austin Cassidy ............................S 72 ** Burkes, Jaivorio OL 6-5 295 Jr. Phoenix, Ariz. (Moon Valley) 8 ** Will Henry ..............................WR 22 Burkhead, Rex RB 5-11 200 Fr. -

2011 Topps Football 2011 Complete Set Hobby Edition

2011 TOPPS FOOTBALL 2011 COMPLETE SET HOBBY EDITION All 440 Base Cards including 110 Rookies from 2011 Topps Football BASE CARDS • 440 • Veterans: 262 NFL pros. • Rookies: 110 hopeful talents. • All-Pro: 2010 NFL First Team All-Pros. • Team Cards: 32 cards featuring each team in the league. • Rookie Premiere: 30 elite 2011 NFL Rookies pose for a HOBBY STORE BENEFITS team photo. • Appeals to Fans & Collectors! • Record Breakers: They made the record book in 2010. • Outstanding Value at a Great Price! • Super Bowl Champions: The Packers and the • Collectors Return Year After Year! Lombardi Trophy! • Ships September - The Start of the NFL Season! • League MVP: Tom Brady • 2010 Rookies Of The Year: Sam Bradford & Ndamukong Suh ® TM & © 2011 The Topps Company, Inc. Topps and Topps Football are trademarks of The Topps Company, Inc. All rights reserved. © 2011 NFL Properties, LLC. Team Names/Logos/Indicia are trademarks of the teams indicated. All other PLUS One 5-Card Pack of Hobby Exclusive NFL-related trademarks are trademarks of the National Football League. Officially Licensed Product of NFL PLAYERS | NFLPLAYERS.COM. Please note that you must obtain the approval of the National Football League Properties in promotional materials that incorporate any marks, designs, logos, etc. of the National Football League or any of its teams, unless the Numbered* Red Base Parallel Cards material is merely an exact depiction of the authorized product you purchase from us. Topps does not, in any manner, make any representations as to whether its cards will attain any future value. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PLUS ONE 5-CARD PACK OF HOBBY EXCLUSIVE NUMBERED RED BASE PARALLEL CARDS 2011 COMPLETE SET CHECKLIST 1 Aaron Rodgers 69 Tyron Smith 137 Team Card 205 John Kuhn 273 LeGarrette Blount 341 Braylon Edwards 409 D.J. -

Patriots at Philadelphia Game Notes

GAME NOTES New England Patriots at New York Giants - August 29, 2012 *Sebastian Vollmer made his 2012 preseason debut and was in the starting lineup at right tackle. Vollmer dressed for the Tampa Bay game but did not start. *QB Ryan Mallett made his second start of the preseason. He started in the Monday Night Football game against Philadelphia on Aug. 20 at Gillette Stadium. Mallett played through the first half before being relieved by Brian Hoyer. Mallett finished the game 8-of-15 for 40 yards. *Hoyer finished 9-of15 for 96 yards. The Patriots and Giants closed out the preseason for the eighth straight year. The Patriots lost to the Giants 6-3 and are now 2-6 in those games. *Of the seven 2012 draft picks, four were in the starting lineup against the Giants. Second-round pick Tavon Wilson started at safety, sixth-round pick Nate Ebner started at safety, seventh-round pick Alfonzo Dennard started at cornerback and seventh-round pick Jeremy Ebert started at wide receiver. *First round draft picks DL Chandler Jones and LB Dont’a Hightower did not start against the Giants after starting the first three preseason games. *DL Jermaine Cunningham had two sacks in the game. He registered a 14-yard sack of QB Eli Manning in the first quarter and a 7-yard sack of David Carr in the second quarter. Cunningham also had three hits on the quarterback and finished the preseason with six hits on the quarterback. *Rookie free agent RB Brandon Bolden started at running back and finished with 15 carries for 59 yards for a 3.9-yard average. -

Patriots at Philadelphia Game Notes

GAME NOTES New England Patriots at Buffalo Bills – September 29, 2019 TEAM NOTES • Patriots off to 4-0 record for ninth time in team history and fifth time under Belichick • Patriots have 26th undefeated month since 2000 • Patriots have now gone 19 straight seasons without being swept in AFC East play • Patriots return blocked punt for a TD for second time under Belichick • D. McCourty ties a team record with a pick in fourth straight game • J.C. Jackson has first NFL game with two interceptions PATRIOTS START 4-0 FOR NINTH TIME IN TEAM HISTORY; FIFTH TIME UNDER BELICHICK The Patriots are off to a 4-0 start for the ninth time in team history (1964, 1974, 1997, 1999, 2004, 2007, 2013, 2015 and 2019) and the fifth time under Bill Belichick. PATRIOTS HAVE NOW WON 18 STRAIGHT AGAINST A FIRST OR SECOND-YEAR QB The Patriots have now won 18 straight games against a first or second-year quarterback, the longest streak in NFL history. The New York Giants (1988-90) and the Los Angeles Rams (1973-79) have the second longest streak at 17 straight wins. PATRIOTS FINISH THE MONTH OF SEPTEMBER UNDEFEATED; 26TH UNDEFEATED MONTH INCE 2000 – TOPS IN NFL The Patriots finished the month of September with a 4-0 record and now have 26 undefeated months since 2000. It is the most undefeated months in the NFL over that span. Indianapolis is second with 16 undefeated months during that time. PATRIOTS UNDEFEATED MONTHS SINCE THE 2000 SEASON (EXCLUDING JANUARY) 2001 ............................................... December 2003 .............. October, November, December 2004 ........................... -

Mike Clay's 2020 NFL Projection Guide

Mike Clay's 2020 NFL Projection Guide Updated: 9/10/2020 Glossary: Page 2-33: Team Projections Page 34-44: QB, RB, WR and TE projections Page 45-48: Category Leader projections Page 49: Projected standings, playoff teams and 2021 draft order Page 50: Projected Strength of Schedule Page 51: Unit Grades Page 52-61: Positional Unit Ranks Understanding the graphics: *The numbers shown are projections for the 2020 NFL regular season (Weeks 1-17). *Some columns may not seem to be adding up correctly, but this is simply a product of rounding. The totals you see are correct. *Looking for sortable projections by position or category? Check out the projections tab inside the ESPN Fantasy game. *'Team stat rankings' is where each team is projected to finish in the category that is shown. *'Unit Grades' is not related to fantasy football and is an objective ranking of each team at 10 key positions. The overall grades are weighted based on positional importance. The scale is 4.0 (best) to 0.1 (worst). A full rundown of Unit Grades can be found on page 51. *'Strength of Schedule Ranking' is based on 2020 rosters (not 2019 team record). '1' is easiest and '32' hardest. See the full list on page 50. *Note that prior to the official release of the NFL schedule (generally late April/early May), the schedule shown includes the correct opponents, but the order is random *Have a question? Contact Mike Clay on Twitter @MikeClayNFL 2020 Arizona Cardinals Projections QUARTERBACK PASSING RUSHING PPR DEFENSE WEEKLY SCORE PROJECTIONS Player Gm Att Comp Yds TD INT -

New England Patriots Vs. Miami Dolphins Sunday, September 18, 2016 • 1:00 P.M

NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS VS. MIAMI DOLPHINS Sunday, September 18, 2016 • 1:00 p.m. • Gillette Stadium # NAME ................... POS # NAME .................. POS 3 Stephen Gostkowski ..... K 3 Andrew Franks ........... K 6 Ryan Allen ................... P PATRIOTS OFFENSE PATRIOTS DEFENSE 4 Matt Darr ................... P WR: 80 Danny Amendola 15 Chris Hogan 18 Matthew Slater 7 Jacoby Brissett ..........QB LE: 95 Chris Long 98 Trey Flowers 8 Matt Moore ..............QB 10 Jimmy Garoppolo .......QB LT: 77 Nate Solder 68 LaAdrian Waddle DT: 97 Alan Branch 96 Anthony Johnson 10 Kenny Stills ............. WR 11 Julian Edelman ......... WR LG: 69 Shaq Mason 62 Joe Thuney DT: 90 Malcom Brown 99 Vincent Valentine 11 DeVante Parker ....... WR 15 Chris Hogan ............. WR 14 Jarvis Landry ........... WR C: 60 David Andrews 75 Ted Karras RE: 93 Jabaal Sheard 98 Trey Flowers 18 Matthew Slater ......... WR 15 Justin Hunter ........... WR 19 Malcolm Mitchell ....... WR RG: 65 Jonathan Cooper 75 Ted Karras LB: 91 Jamie Collins 51 Barkevious Mingo 17 Ryan Tannehill ..........QB 21 Malcolm Butler ........... CB RT: 61 Marcus Cannon 71 Cameron Fleming LB: 54 Dont'a Hightower 52 Elandon Roberts 19 Jakeem Grant .......... WR 22 Justin Coleman ..........DB TE: 87 Rob Gronkowski 88 Martellus Bennett 81 Clay Harbor LB: 55 Jonathan Freeny 58 Shea McClellin 20 Reshad Jones ............. S 23 Patrick Chung .............. S 86 AJ Derby 21 Jordan Lucas ............ CB 24 Cyrus Jones ............... CB WR: 11 Julian Edelman 19 Malcolm Mitchell RCB: 26 Logan Ryan 24 Cyrus Jones 25 Eric Rowe 22 Isaiah Pead .............. RB 25 Eric Rowe ..................DB QB: 10 Jimmy Garoppolo 7 Jacoby Brissett LCB: 21 Malcolm Butler 22 Justin Coleman 31 Jonathan Jones 23 Jay Ajayi ................. -

Falcons Offense Falcons Specialists Falcons

vs. SUNDAY, September 29, 2013 - Georgia Dome 2 Matt Ryan ..................................... QB FALCONS OFFENSE FALCONS DEFENSE 3 Stephen Gostkowski ........................ K 3 Matt Bryant ...................................... K 6 Ryan Allen ....................................... P WR 11 Julio Jones 83 Harry Douglas 15 Kevin Cone RE 50 Osi Umenyiora 99 Stansly Maponga 4 Dominique Davis ........................... QB 11 Julian Edelman............................. WR LT 72 Sam Baker 73 Ryan Schraeder 65 Jeremy Trueblood DT 91 Corey Peters 94 Peria Jerry 5 Matt Bosher ..................................... P 12 Tom Brady .................................... QB LG 63 Justin Blalock 69 Harland Gunn DT 95 Jonathan Babineaux 92 Travian Robertson 11 Julio Jones .................................. WR 15 Ryan Mallett .................................. QB C 66 Peter Konz 61 Joe Hawley 15 Kevin Cone ................................... WR LE 96 Jonathan Massaquoi 98 Cliff Matthews 93 Malliciah Goodman 17 Aaron Dobson .............................. WR RG 75 Garrett Reynolds 69 Harland Gunn 19 Drew Davis .................................. WR OLB 59 Joplo Bartu 53 Omar Gaither 18 Matthew Slater ............................. WR RT 76 Lamar Holmes 73 Ryan Schraeder 65 Jeremy Trueblood 21 Desmond Trufant .......................... CB MLB 52 Akeem Dent 55 Paul Worrilow 22 Stevan Ridley ................................ RB TE 88 Tony Gonzalez 86 Chase Coffman 80 Levine Toilolo 22 Asante Samuel .............................. CB OLB 54 Stephen Nicholas 51 -

Final Rosters

Rosters 2001 Final Rosters Injury Statuses: (-) = OK; P = Probable; Q = Questionable; D = Doubtful; O = Out; IR = On IR. Baltimore Hownds Owner: Zack Wilz-Knutson PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. Houston Stallions Owner: Ian Wilz PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR Dave Brown QB ARI - Jake Plummer QB ARI - Tim Couch QB CLE - Duce Staley RB PHI - Ricky Watters RB SEA IR Ron Dayne RB NYG - Stanley Pritchett RB CHI - Zack Crockett RB OAK - Derrick Mason WR TEN - Johnnie Morton WR DET - Laveranues Coles WR NYJ - Willie Jackson WR NOR - Alge Crumpler TE ATL - Dave Moore TE TAM - Matt Stover K BAL - Paul Edinger K CHI - 2001 Final Rosters 1 Rosters Chicago Bears Defense CHI - Pittsburgh Steelers Defense PIT - Carolina Panthers Special Team CAR - Dallas Cowboys Special Team DAL - Dan Reeves Head Coach ATL - Dick Jauron Head Coach CHI - NYC Dark Force Owner: D.J. Wendell NFL ON PLAYER POSITION INJ STARTER RESERVE TEAM IR Aaron Brooks QB NOR - Daunte Culpepper QB MIN - Jeff Blake QB NOR - Bob Christian RB ATL - Emmitt Smith RB DAL - James Stewart RB DET - Jim Kleinsasser RB MIN - Warrick Dunn RB TAM - Cris Carter WR MIN - James Thrash WR PHI - Jerry Rice WR OAK - Travis Taylor WR BAL - Dwayne Carswell TE DEN - Jay Riemersma TE BUF - Jay Feely K ATL - Joe Nedney K TEN - San Francisco 49ers Defense SFO - Defense TAM - 2001 Final Rosters 2 Rosters Tampa Bay Buccaneers Minnesota Vikings Special Team MIN - Oakland Raiders Special Team OAK - Dick Vermeil Head Coach KAN - Steve Mariucci Head Coach SFO - Las Vegas Owner: ?? PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. -

Seminoles in the Nfl Draft

137 PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME All-time Florida State gridiron greats Walter Jones and Derrick Brooks are used to making history. The longtime NFL stars added an achievement that will without a doubt move to the top of their accolade-filled biographies when they were inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame inAugust, 2014. Jones and Brooks became the first pair of first-ballot Hall of Famers from the same class who attended the same college in over 40 years. The pair’s journey together started 20 years ago. Just as Brooks was wrapping up his All-America career at Florida State in 1994, Jones was joining the Seminoles out of Holmes Community College (Miss.) for the 1995 season. DERRICK BROOKS Linebacker 1991-94 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame WALTER JONES Offensive Tackle 1995-96 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame 138 PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME They never played on the same team at Florida State, but Jones distinctly remembers how excited he was to follow in the footsteps of the star linebacker whom he called the face of the Seminoles’ program. Jones and Brooks were the best at what they did for over a decade in the NFL. Brooks went to 11 Pro Bowls and never missed a game in 14 seasons (all with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers), while Jones became the NFL’s premier left tackle, going to nine Pro Bowls over 12 seasons with the Seattle Seahawks. Both retired in 2008, and, six years later, Jones and Brooks were teammates for the first time as first-ballot Hall of Famers.