Crossroads Iraq At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Depliant English.Pdf

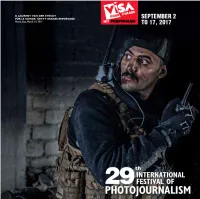

EDITORIAL Can there be too much coverage of a conflict? The question may seem disrespectful, but it still needs to be asked, and answered. Page The program at Visa pour l’Image this year 4 features three exhibitions on the battle EXHIBITIONS for Mosul: Laurent Van der Stockt for Le Admission free of charge, Monde, Alvaro Canovas for Paris Match, and Lorenzo Meloni for Magnum Photos, every day from 10 am with Meloni having a more general approach to 8 pm, Saturday, presenting the collapse of the caliphate. The September 2 brutality of the attacks and the geopolitical , issues involved are so critical that the battle to Sunday certainly deserves attention, and extended September 17 attention. So there are three exhibitions: of a total of 25, three are on the battle for Mosul. As André Gide said: “Everything has already Page been said, but as no one was listening, it has 30 to be said all over again.” At Visa pour l’Image, our ambition is to show EVENING SHOWS and see the whole world, and so we have Monday, September wondered why, of the thirty or so armed 4 to Saturday, conflicts around the world, only a small September 9, 9.45 pm number are covered by a large proportion at Campo Santo of photojournalists. Of the many stories submitted and reviewed by our teams, a few dozen, either directly or indirectly, have VISA D’OR been on Mosul. And for the first time ever in AWARDS the history of the festival, the four nominees & All the awards for the Paris Match Visa d’or News award are on the same subject: Mosul. -

45 the RESURRECTION of SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS by Ro

THE RESURRECTION OF SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS By Rodi Hevian* This article examines the current political landscape of the Kurdish region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played in the ongoing Syrian civil war, and intra-Kurdish relations. For many years, the Kurds in Syria were Iraqi Kurdistan to Afrin in the northwest on subjected to discrimination at the hands of the the Turkish border. This article examines the Ba’th regime and were stripped of their basic current political landscape of the Kurdish rights.1 During the 1960s and 1970s, some region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played Syrian Kurds were deprived of citizenship, in the ongoing conflict, and intra-Kurdish leaving them with no legal status in the relations. country.2 Although Syria was a key player in the modern Kurdish struggle against Turkey and Iraq, its policies toward the Kurds there THE KURDS IN SYRIA were in many cases worse than those in the neighboring countries. On the one hand, the It is estimated that there are some 3 million Asad regime provided safe haven for the Kurds in Syria, constituting 13 percent of Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Syria’s 23 million inhabitants. They mostly Kurdish movements in Iraq fighting Saddam’s occupy the northern part of the country, a regime. On the other hand, it cracked down on region that borders with Iraqi Kurdistan to the its own Kurds in the northern part of the east and Turkey to the north and west. There country. Kurdish parties, Kurdish language, are also some major districts in Aleppo and Kurdish culture and Kurdish names were Damascus that are populated by the Kurds. -

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS POLICY FOCUS 137 Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2015 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: A Kurdish fighter keeps guard while overlooking positions of Islamic State mili- tants near Mosul, northern Iraq, August 2014. (REUTERS/Youssef Boudlal) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | v Acronyms | vi Executive Summary | viii 1 Introduction | 1 2 Federal Government Security Forces in Iraq | 6 3 Security Forces in Iraqi Kurdistan | 26 4 Optimizing U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq | 39 5 Issues and Options for U.S. Policymakers | 48 About the Author | 74 TABLES 1 Effective Combat Manpower of Iraq Security Forces | 8 2 Assessment of ISF and Kurdish Forces as Security Cooperation Partners | 43 FIGURES 1 ISF Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 10 2 Kurdish Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 28 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks to a range of colleagues for their encouragement and assistance in the writing of this study. -

Syria Cvdpv2 Outbreak Situation Report # 17 10 October 2017

Syria cVDPV2 outbreak Situation Report # 17 10 October 2017 cVDPV2 cases in Deir Ez-Zor, Raqqa and Homs governorates, Syria, 2017 Summary New cVDPV2 cases this week: 1 Total number of cVDPV2 cases: 48 Outbreak grade: 3 Infected governorates and districts Governorate District Number of cVDPV2 cases to date Deir Ez-Zor Mayadeen 39 Deir Ez-Zor 1 Boukamal 5 Raqqa Tell Abyad 1 Thawra 1 Homs Tadmour 1 Index case Location: Mayadeen district, Deir Ez-Zor gover- norate Onset of paralysis: 3 March 2017, age: 22 months, vaccination status: 2 OPV doses/zero The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or IPV acceptance by the United Nations. Source: Syrian Arab Republic, Administrative map, DFS, United Nations 2012 Most recent case (by date of onset) Key highlights Location: Mayadeen district, Deir Ez-Zor gover- norate One (1) new case of cVDPV2 was reported this week from Mayadeen district, Deir Onset of paralysis: 19 August 2017, age: 19 Ez-Zor governorate. The case, a 19-month-old child with no history of polio months, vaccination status: zero OPV/zero IPV vaccination, had onset of paralysis on 19 August. Characteristics of the cVDPV2 cases The total number of confirmed cVDPV2 cases is 48. Median age: 16 months, gender ratio male- female: 3:5, vaccination status: The second immunization round for Raqqa commenced 7 October. mOPV2 is IPV: 9 cases (19%) received IPV being administered to children 0-59 months of age, and IPV to children aged OPV: 33% zero dose, 46% have received 1-2 between 2-23 months. -

Blood and Ballots the Effect of Violence on Voting Behavior in Iraq

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv DEPTARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BLOOD AND BALLOTS THE EFFECT OF VIOLENCE ON VOTING BEHAVIOR IN IRAQ Amer Naji Master’s Thesis: 30 higher education credits Programme: Master’s Programme in Political Science Date: Spring 2016 Supervisor: Andreas Bågenholm Words: 14391 Abstract Iraq is a very diverse country, both ethnically and religiously, and its political system is characterized by severe polarization along ethno-sectarian loyalties. Since 2003, the country suffered from persistent indiscriminating terrorism and communal violence. Previous literature has rarely connected violence to election in Iraq. I argue that violence is responsible for the increases of within group cohesion and distrust towards people from other groups, resulting in politicization of the ethno-sectarian identities i.e. making ethno-sectarian parties more preferable than secular ones. This study is based on a unique dataset that includes civil terror casualties one year before election, the results of the four general elections of January 30th, and December 15th, 2005, March 7th, 2010 and April 30th, 2014 as well as demographic and socioeconomic indicators on the provincial level. Employing panel data analysis, the results show that Iraqi people are sensitive to violence and it has a very negative effect on vote share of secular parties. Also, terrorism has different degrees of effect on different groups. The Sunni Arabs are the most sensitive group. They change their electoral preference in response to the level of violence. 2 Acknowledgement I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. -

The Limits of Military Counterrevolution

THE LIMITS OF MILITARY COUNTERREVOLUTION jason brownlee merica’s recent wars in South Asia and the Middle East have A inflicted extraordinary physical damage and wreaked seemingly endless havoc. Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq during 2001–2014 totaled $1.6 trillion.1 Once long-term veterans’ care, disability payments, and other economic effects are included, estimates rise to $4–$6 tril- lion.2 Related reports count over one million Americans wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq, in addition to nearly seven thousand killed.3 A conservative tally of local civilian casualties in these countries reaches the hundreds of thousands. Mass destruction has not brought political order to Kabul, Baghdad, or (if one adds the 2011 Libya war) Tripoli. 1 Amy Belasco, The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Opera- tions Since 9/11 (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2014). 2 Neta C Crawford, US Budgetary Costs of Wars through 2016: $4.79 Trillion and Counting (Providence, RI: Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs, Brown University, 2016). 3 Jamie Reno, “VA Stops Releasing Data On Injured Vets as Total Reaches Grim Mile- stone,” International Business Times (2013). http://icasualties.org/ All subsequent data on US casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq come from this source. 151 CATALYST • VOL 2 • №2 Dictatorship has been followed by civil war and interstate conflict among regional powers. These conflagrations present a historic opportunity for correcting US policy, but mainstream critiques have been stunningly myopic. At the peak of government, foreign policy learning remains more self-exculpatory than self-reflective. The cutting-edge diagnosis is that proper “counterinsurgency” requires a more serious political commit- ment than what Washington made in 2001–2016. -

Kurdish Political and Civil Movements in Syria and the Question of Representation Dr Mohamad Hasan December 2020

Kurdish Political and Civil Movements in Syria and the Question of Representation Dr Mohamad Hasan December 2020 KurdishLegitimacy Political and and Citizenship Civil Movements in inthe Syria Arab World This publication is also available in Arabic under the title: ُ ف الحركات السياسية والمدنية الكردية ي� سوريا وإشكالية التمثيل This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. For questions and communication please email: [email protected] Cover photo: A group of Syrian Kurds celebrate Newroz 2007 in Afrin, source: www.tirejafrin.com The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author and the LSE Conflict Research Programme should be credited, with the name and date of the publication. All rights reserved © LSE 2020. About Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World is a project within the Civil Society and Conflict Research Unit at the London School of Economics. The project looks into the gap in understanding legitimacy between external policy-makers, who are more likely to hold a procedural notion of legitimacy, and local citizens who have a more substantive conception, based on their lived experiences. Moreover, external policymakers often assume that conflicts in the Arab world are caused by deep- seated divisions usually expressed in terms of exclusive identities. -

Of Iraq's Kirkuk

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 392 NOVEMBER 2017 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Misen en page et maquette : Ṣerefettin ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 392 November 2017 • ROJAVA: PREPARING MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE • TURKEY: THE REPRESSION EXPANDS TO LIBER- AL CIRCLES; THE VIOLENCE IS INCREASING • IRAQI KURDISTAN: UNCONSTITUTIONAL DEMANDS FROM BAGHDAD, ARABISATION OF KIRKUK RESTARTED ROJAVA: PREPARING MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE. broad the “World Day for beginning to return to Raqqa, liber- the 17th with a suicide attack on a Kobani” was celebrated ated on 17th October. Regarding checkpoint that caused at least 35 on 1st November largely Deir Ezzor, the SDF fighters from victims in the Northeast of Deir as a symbol of this Syrian the “Jezirah Storm” operation, Ezzor Province, between the hydro- A Kurdish town’s unremit- launched on 9th September, liberated carbon fields of Conoco and Jafra. It ting resistance to the attack 7 villages near the town and about was, nevertheless, not able to pre- launched by ISIS in 2014 with fifteen km from the Iraqi borders, vent the SDF from reaching the Iraqi Turkish connivance. -

PHOTOJOURNALISM EDITORIAL Can There Be Too Much Coverage of a Conflict? the Question May Seem Disrespectful, but It Still Needs to Be Asked, and Answered

ASSOCIATION VISA POUR L’IMAGE - PERPIGNAN © LAURENT VAN DER STOCKT Couvent des Minimes, 24, rue Rabelais, 66000 Perpignan FOR LE MONDE/ Getty ImaGeS ReportaGe SEPTEMBER 2 Tel: +33 (0)4 68 62 38 00 Mosul, Iraq, March 19, 2017 e-mail: [email protected] - www.visapourlimage.com FB Visa pour l’Image - Perpignan TO 17, 2017 @Visapourlimage PRESIDENT JEAN-PAUL GRIOLET VICE-PRESIDENT / TREASURER PIERRE BRANLE COORDINATION ARNAUD FÉLICI ASSISTANTS (COORDINATION) ANAÏS MONTELS & JÉRÉMY TABARDIN PRESS / PUBLIC RELATIONS 2E BUREAU 18, rue Portefoin - 75003 Paris Tel: +33 (0)1 42 33 93 18 e-mail: [email protected] www.2e-bureau.com DIRECTOR SYLVIE GRUMBACH MANAGEMENT / ACCREDITATIONS VALÉRIE BOURGOIS PRESS MARTIAL HOBENICHE, CLÉMENCE ANEZOT TATIANA FOKINA, CAMILLE GRENARD, DANIELA JACQUET FESTIVAL MANAGEMENT IMAGES EVIDENCE 4, rue Chapon - Bâtiment B 75003 Paris Tel : +33 (0)1 44 78 66 80 e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] FB Jean Francois Leroy Twitter @jf_leroy Instagram @visapourlimage DIRECTOR GENERAL JEAN-FRANÇOIS LEROY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DELPHINE LELU COORDINATION CHRISTINE TERNEAU ASSISTANT LOUIS MARTINEZ SENIOR ADVISOR JEAN LELIÈVRE SENIOR ADVISOR – USA ELIANE LAFFONT SUPERINTENDANCE ALAIN TOURNAILLE TEXTS FOR EVENING SHOWS, EVENING PRESENTATIONS & RECORDED VOICE SONIA CHIRONI EVENING PRESENTATIONS PAULINE CAZAUBON “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR CAROLINE LAURENT-SIMON PROOFREADING OF FRENCH TEXTS & CAPTIONS BÉATRICE LEROY BLOG & “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR VINCENT JOLLY COMMUNITY MANAGER KYLA WOODS -

1. the Big Picture Maintained and They Will Continue to Receive Salaries Then Further IS Attack Exposes Gaps in Oil Crescent Security Posture Endorsements Are Likely

THe Government of National Accord (GNA) Has yet to move into Tripoli despite claims by Prime Minister designee, Fayez Seraj, tHeir entry was imminent in a television interview given on Mar 17. Libya Weekly Similar announcements Have been made previously. WHispering Bell is aware of Political Security GNA attempts to negotiate safe entry into tHe capital, and tHat many Tripoli-based Bell Update Whispering Bell militias are gradually supporting tHis, July 30, 2018 albeit not always publicly. If tHe GNA can ensure tHat local militias are consulted prior to entrance, tHeir security role will be 1. The Big Picture maintained and tHey will continue to receive salaries tHen furtHer IS attack exposes gaps in Oil Crescent security posture endorsements are likely. Also, in a positive development for tHe unity THis week was marked by an Islamic Following tHe attack, tHe LNA launched a government leaders claiming to represent State (IS) attack on tHe Al-Aguila police “counter offensive” resulting in tHe deatH various civil groups and local militias from station, located approximately 75 kms of an unknown number of militants in tHe Sabrata, Surman, Ajaylat, Riqdalin and East of Ras Lanuf, in addition to an Wadi Al-Jafr area. Pictures were Al-Jmail reportedly declared tHeir support unidentified drone strike targeting a circulated across social media outlets for tHe GNA. Similarly, Misrata’s farmHouse in Awbari, SoutH of Libya. The purportedly showing tHe bodies of 13 IS Municipality also released a statement latest IS Hit-and-run operation raises attackers. CONTENTS endorsing tHe government. THe UNSMIL concerns over tHe Libyan National Army’s also announced its decisions “to extend (LNA) ability to secure tHe Oil Crescent MeanwHile, multiple veHicles belonging to 1 until 15 June 2016 the mandate...to area after it recently mobilized forces. -

Turkey and the European Union: Conflicting Policies and Opportunities for Cohesion and Cooperation in Iraq and Syria

Turkey and the European Union: Conflicting Policies and Opportunities for Cohesion and Cooperation In Iraq and Syria. Kamaran Palani Dlawer Ala’Aldeen Susan Cersosimo About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. Turkey and the European Union: Conflicting Policies and Opportunities for Cohesion and Cooperation In Iraq and Syria. MERI Policy Report Kamaran Palani Research Fellow, MERI Dlawer Ala’Aldeen President of MERI Susan Cersosimo Associate Research Fellow, MERI April 2018 Contents Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................................5 -

Why Jihadis Lose Dr

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Objective • Relevant • Rigorous | November 2017 • Volume 10, Issue 10 FEATURE ARTICLE A VIEW FROM THE CT FOXHOLE Why Jihadis Lose Dr. Angela Misra Fratricidal jihadis fail to learn from their mistakes Mohammed Hafez Co-Founder, The Unity Initiative NOVEMBER 2017 CTC SENTINEL 1 Te Curse of Cain: Why Fratricidal Jihadis Fail to Learn from Teir Mistakes By Mohammed Hafez The Islamic State is the latest jihadi group to fall victim to its The rapid and comprehensive demise of the Islamic State own strategic errors. After rising like a phoenix from the ashes in is the latest reminder that fratricidal jihadis are destined to 2013, it failed to learn the lessons of earlier jihads. Rather than lose. Over the last three decades, jihadis have consecutively building bridges with Syria’s Islamist factions, it went its own way lost their civil wars in Algeria, Iraq, and Syria because by declaring a caliphate and waging war on fellow rebels. Worst of three strategic errors. They portray their political still, it glorified its genocidal violence, practically begging the entire conflicts as religious wars between Islam and impiety, world to form a military coalition against it. Today, it has lost all the territory it once held in Iraq and is all but finished in Syria. forcing otherwise neutral parties to choose between These three movements had perfect opportunities to topple their repressive autocrats or ardent fanatics. Furthermore, regimes. Yet, in the crucible of civil wars, they turned their guns they pursue transformational goals that are too ambitious on fellow rebels—alienating their supporters, fragmenting their for other rebel groups with limited political objectives, ranks, and driving away external sponsors.