Dr. SATAN´S ECHO CHAMBER: REGGAE, TECHNOLOGY and the DIASPORA PROCESS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

Media and Advertising Information Why Advertise on Bigup Radio? Ranked in the Top 50,000 of All Sites According to Amazon’S Alexa Service

Media and Advertising Information Why Advertise on BigUp Radio? Ranked in the top 50,000 of all sites according to Amazon’s Alexa service Audience 16-34 year-old trend-setters and early adopters of new products. Our visitors purchase an average of $40–$50 each time they buy music on bigupradio.com and more than 30% of those consumers are repeat customers. Typical Traffic More than 1,000,000 unique page views per month Audience & Traffic 1.5 million tune-ins to the BigUp Radio stations Site Quick Facts Over 75,000 pod-cast downloads each month of BigUp Radio shows Our Stations Exclusive DJ Shows A Strong Image in the Industry Our Media Player BigUp Radio is in touch with the biggest artists on the scene as well as the Advertising Opportunities hottest upcoming new artists. Our A/R Dept listens to every CD that comes in selecting the very best tracks for airplay on our 7 stations. Among artists that Supporting Artists’ Rights have been on BigUp Radio for interviews and special guest appearances are: Rate Card Beenie Man Tanya Stephens Anthony B Contact Information: Lil Jon I Wayne TOK Kyle Russell Buju Banton Gyptian Luciano (617) 771.5119 Bushman Collie Buddz Tami Chynn [email protected] Cutty Ranks Mr. Vegas Delly Ranx Damian Marley Kevin Lyttle Gentleman Richie Spice Yami Bolo Sasha Da’Ville Twinkle Brothers Matisyahu Ziggi Freddie McGregor Jr. Reid Worldwide Reggae Music Available to anyone with an Internet connection. 7 Reggae Internet Radio Stations Dancehall, Roots, Dub, Ska, Lovers Rock, Soca and Reggaeton. -

Read Or Download

afrique.q 7/15/02 12:36 PM Page 2 The tree of life that is reggae music in all its forms is deeply spreading its roots back into Afri- ca, idealized, championed and longed for in so many reggae anthems. African dancehall artists may very well represent the most exciting (and least- r e c o g n i z e d ) m o vement happening in dancehall today. Africa is so huge, culturally rich and diverse that it is difficult to generalize about the musical happenings. Yet a recent musical sampling of the continent shows that dancehall is begin- ning to emerge as a powerful African musical form in its own right. FromFrom thethe MotherlandMotherland....Danc....Danc By Lisa Poliak daara-j Coming primarily out of West Africa, artists such as Gambia’s Rebellion D’Recaller, Dancehall Masters and Senegal’s Daara-J, Pee GAMBIA Froiss and V.I.B. are creating their own sounds growing from a fertile musical and cultural Gambia is Africa’s cross-pollination that blends elements of hip- dancehall hot spot. hop, reggae and African rhythms such as Out of Gambia, Rebel- Senegalese mbalax, for instance. Most of lion D’Recaller and these artists have not yet spread their wings Dancehall Masters are on the international scene, especially in the creating music that is U.S., but all have the musical and lyrical skills less rap-influenced to explode globally. Chanting down Babylon, than what is coming these African artists are inspired by their out of Senegal. In Jamaican predecessors while making music Gambia, they’re basi- that is uniquely their own, praising Jah, Allah cally heavier on the and historical spiritual leaders. -

Shilliam, Robbie. "Dread Love: Reggae, Rastafari, Redemption." the Black Pacific: Anti- Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "Dread Love: Reggae, RasTafari, Redemption." The Black Pacific: Anti- Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 109–130. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 23 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 23 September 2021, 11:28 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Dread Love: Reggae, RasTafari, Redemption Introduction Over the last 40 years roots reggae music has been the key medium for the dissemination of the RasTafari message from Jamaica to the world. Aotearoa NZ is no exception to this trend wherein the direct action message that Bob Marley preached to ‘get up stand up’ supported the radical engagements in the public sphere prompted by Black Power.1 In many ways, Marley’s message and demeanour vindicated the radical oppositional strategies that activists had deployed against the Babylon system in contradistinction to the Te Aute Old Boy tradition of tactful engagement. No surprise, then, that roots reggae was sometimes met with consternation by elders, although much of the issue revolved specifically around the smoking of Marijuana, the wisdom weed.2 Yet some activists and gang members paid closer attention to the trans- mission, through the music, of a faith cultivated in the Caribbean, which professed Ethiopia as the root and Haile Selassie I as the agent of redemption. And they decided to make it their faith too. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

A Music Genre That Originated in Jamaica in the 1960'S. Roots Reggae

Music Year 2 In this unit of work children will learn a song entitled, ‘Zoo Time’. Children will explore elements of the song such as, pulse, rhythm and pitch. The song is the Reggae style of music and children will explore this genre and it’s key indicators. In this unit children will: Key Vocabulary • Listen and appraise the song Zoo Time. Reggae: A music genre that originated in • Learn and perform Zoo Time. • Learn about the Reggae style of music and where Jamaica in the 1960’s. it come from. Roots Reggae: Music that deals with • Learn about the key indicators of Reggae. social and racial issues and brings • Learn about key Reggae artists such as Bob in elements of Rastafari. Marley, UB40, Aswad, Donald Jay Fagen, Marcia Foreground: What can be mostly heard/more prominently in a piece of Griffiths, Jimmy Cliff. • Listen to Reggae songs, e.g. Kingston Town. music. • Look at where Reggae fits in the historical Lyrics: The words to a song. context of music. Rastafarian: A person who follows a set • Played untuned percussion instruments. of beliefs/a religion developed in Jamaica in the 1930’s. Off-beat: If a piece of music has 4 Prior Learning EYFS: Develops preferences for forms of expression, creates beats in a bar i.e. 1 2 3 4, to movement in response to music, makes up rhythms, clap on the off-beat you would clap captures experiences and responses with music, represents on beats 2 and 4 not 1 and 3. thoughts and feelings of music. Children sing songs, make Backing vocal: Singers who provide a music and experiment with ways of changing them. -

Various Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends Country: UK Released: 1990 Style: Roots Reggae, Dub, Rocksteady MP3 version RAR size: 1668 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1377 mb WMA version RAR size: 1298 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 963 Other Formats: AIFF AC3 AUD AAC MP3 MPC FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits My Conversation A1 –Slim Smith And The Uniques Written-By – K. Smith* 100,000 Dollars A2 –The Success All Stars Written-By – Rupie Edwards Doctor Come Quick A3 –Hugh Roy Junior* Written-By – Hugh Roy Jnr.* Half Way Tree Pressure A4 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson Mi Nuh Matta A5 –El Cisco Delgado Written-By – Delgado* Tribute To Slim Smith A6 –Tyrone Downie Written-By – Downie* Doctor Satan Echo Chamber A7 –The Success All Stars Written-By – Rupie Edwards Yamaha Skank A8 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson Riding With Mr. Lee B1 –Earl "Chinna" Smith Written-By – Earl "China" Smith* President A Mash Up The Resident B2 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson President Rock B3 –Joe White Written-By – J. White* Dew Of Herman B4 –Bongo Herman & Les* Written-By – Bongo Herman, Les* Give Me The Right B5 –The Heptones Written-By – Unknown Artist Underworld Way B6 –Shorty The President Written-By – Rupie Edwards Christmas Rock B7 –Rupie Edwards Written-By – Rupie Edwards Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Trojan Records Copyright (c) – Trojan Records Marketed By – Trojan Sales Ltd. Pressed By – Adrenalin Mastered At – PRT Studios Credits Design – Steve Barrow, Steve Lane Liner Notes – Steve Barrow Producer – Rupie Edwards (tracks: A2 - A8, B1 - B7) Producer [uncredited] – Bunny Lee (tracks: A1) Remastered By – Malcolm Davies Notes Digitally remastered issue of "Yamaha Skank" with additional tracks. -

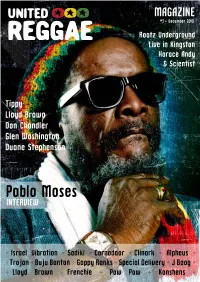

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

Dr. SATAN´S ECHO CHAMBER: RAGGAE, TECHNOLGY and the DIASPORA PROCESS

The Journal of Kitsch, Camp and Mas Culture The Journal of Kitsch, Camp and Mass Culture Volume 1 / 2018 Dr. SATAN´S ECHO CHAMBER: RAGGAE, TECHNOLGY AND THE DIASPORA PROCESS Louis Chude-Sokei Boston University, [email protected] Louis Chude-Sokei Dr. SATAN´S ECHO CHAMBER: RAGGAE, TECHNOLOGY AND THE DIASPORA PROCESS1 Louis Chude-Sokei Author’s Note. At this point I’m proud to have forgotten how many times this essay has appeared. It was ini- tially presented as the inaugural “Bob Marley Lecture” for the opening of the Institute of Car- ibbean Studies’ Reggae Studies Unit at the University of the West Indies, in Kingston Jamaica in 1997 but has taken on a life of its own as many of its insights and declarations have been found to be continually valid as electronic music has grown and sound studies has itself be- come a formal discipline. I’m unable to read it now due to my personal history with the piece and its immediate responses, but it did serve as the primary inspiration for my more recent book, The Sound of Culture: Diaspora and Black Technopoetics (Wesleyan University Press, 2015). It will also be the titular essay in a forthcoming collection, “Dr. Satan’s Echo Chamber” and Other Essays also contracted with Wesleyan for publication in 2020. I’m incredibly pleased and honored that Popular Inquiry has seen fit to imbue it with continued life and rele- vance. Louis Chude-Sokei. Boston, Massachusetts, 2018. Let me humbly begin with the history of the Universe. Western science has provided us with a myth of origins in the "Big Bang" theory, which locates the beginning of all things in a primal explosion from which the stars, moons, planets, universes and even humanity are birthed. -

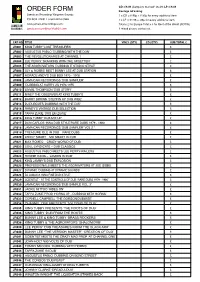

Order Form Order Form

CD: £9.49 (Samplers marked* £6.49) LP: £9.49 ORDER FORM Postage &Packing: Jamaican Recording/ Kingston Sounds 1 x CD = 0.95p + 0.35p for every additional item PO BOX 32691 London W14 OWH 1 x LP = £1.95 + .85p for every additional item JAMAICAN www.jamaicanrecordings.com Total x 2 for Europe Total x 3 for Rest of the World (ROTW) RECORDINGS [email protected] If mixed please contact us. CAT NO. TITLE VINLY (QTY) CD (QTY) SUB TOTAL £ JR001 KING TUBBY 'LOST TREASURES' £ JR002 AUGUSTUS PABLO 'DUBBING WITH THE DON' £ JR003 THE REVOLUTIONARIES AT CHANNEL 1 £ JR004 LEE PERRY 'SKANKING WITH THE UPSETTER' £ JR005 THE AGGROVATORS 'DUBBING IT STUDIO STYLE' £ JR006 SLY & ROBBIE MEET BUNNY LEE AT DUB STATION £ JR007 HORACE ANDY'S DUB BOX 1973 - 1976 £ JR008 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS 'DUB SAMPLER' £ JR009 'DUBBING AT HARRY J'S 1970-1975 £ JR010 LINVAL THOMPSON 'DUB STORY' £ JR011 NINEY THE OBSERVER AT KING TUBBY'S £ JR012 BARRY BROWN 'STEPPIN UP DUB WISE' £ JR013 DJ DUBCUTS 'DUBBING WITH THE DJS' £ JR014 RANDY’S VINTAGE DUB SELECTION £ JR015 TAPPA ZUKIE ‘DUB EM ZUKIE’ £ JR016 KING TUBBY ‘DUB MIX UP’ £ JR017 DON CARLOS ‘INNA DUB STYLE’RARE DUBS 1979 - 1980 £ JR018 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS 'DUB SAMPLER' VOL 2 * £ JR019 TREASURE ISLE IN DUB – RARE DUBS £ JR020 LEROY SMART – MR SMART IN DUB £ JR021 MAX ROMEO – CRAZY WORLD OF DUB £ JR022 SOUL SYNDICATE – DUB CLASSICS £ JR023 AUGUSTUS PABLO MEETS LEE PERRY/WAILERS £ JR024 RONNIE DAVIS – ‘JAMMIN IN DUB’ £ JR025 KING JAMMY’S DUB EXPLOSION £ JR026 PROFESSIONALS MEETS THE AGGRAVATORS AT JOE GIBBS £ JR027 DYNAMIC ‘DUBBING AT DYNAMIC SOUNDS’ £ JR028 DJ JAMAICA ‘INNA FINE DUB STYLE’ £ JR029 SCIENTIST - AT THE CONTROLS OF DUB ‘RARE DUBS 1979 - 1980’ £ JR030 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS ‘DUB SAMPLE VOL. -

The Seven Voyages of Captain Sinbad Mp3, Flac, Wma

Captain Sinbad The Seven Voyages Of Captain Sinbad mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: The Seven Voyages Of Captain Sinbad Country: UK Released: 2007 Style: Roots Reggae, Dancehall MP3 version RAR size: 1692 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1278 mb WMA version RAR size: 1762 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 527 Other Formats: MMF MPC MP2 RA DXD XM ADX Tracklist A1 Bam Salute A2 All Over Me A3 Wa-Dat A4 Girls Girls A5 Sugar Ray B1 Sinbad And The Eye Of The Tiger B2 Construction Plan B3 Fisherman B4 Morning Teacher B5 Mary Moore Credits Artwork By [Cover] – Tony McDermott Backing Band – Roots Radics* Engineer – Soldgie Engineer, Mixed By – Scientist Producer – Henry 'Junjo' Lawes* Notes Recorded and mixed at Channel One. p 1982 c 2007 Greensleeves Records Ltd. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 601811103418 Other: LC 05923 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Seven Voyages Of Captain Greensleeves GREL 34 Captain Sinbad (LP, GREL 34 UK 1982 Sinbad Records Album) The Seven Voyages Of Captain none Captain Sinbad (LP, Bad 2000 Music none Jamaica Unknown Sinbad Album, RP) The Seven Voyages Of Captain Captain Sinbad (LP, Greensleeves none none UK 2007 Sinbad Album, Promo, RE, Records W/Lbl) Greensleeves The Seven Voyages Of Captain Records, GREL 34 Captain Sinbad (LP, GREL 34 US 1982 Sinbad Shanachie Records Album) Corp. The Seven Voyages Of Captain Greensleeves GREWCD34 Captain Sinbad (CD, GREWCD34 UK 2007 Sinbad Records Album, RE, RM) Related Music albums to The Seven Voyages Of Captain Sinbad by Captain Sinbad Sugar Minott - Hard Time Pressure Basil Rathbone - Sinbad The Sailor John McLean / Captain Sinbad - Came Into The Dance Geoff Hughes - Sinbad Captain Sinbad - 51 Storm Captain Simbad / Ashanti Waugh - Sister Mircle / Funny Love Captain Sinbad - Progress A The Best / Progress Dub Turbo Belly / Daddy Screw - Needle Eye / Ring Ticky Ting Ting.