Dr. SATAN´S ECHO CHAMBER: RAGGAE, TECHNOLGY and the DIASPORA PROCESS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

Dennis Brown ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The

DATE March 27, 2003 e TO Vartan/Um Creative Services/Meire Murakami FROM Beth Stempel EXTENSION 5-6323 SUBJECT Dennis Brown COPIES Alice Bestler; Althea Ffrench; Amy Gardner; Andy McKaie; Andy Street; Anthony Hayes; Barry Korkin; Bill Levenson; Bob Croucher; Brian Alley; Bridgette Marasigan; Bruce Resnikoff; Calvin Smith; Carol Hendricks; Caroline Fisher; Cecilia Lopez; Charlie Katz; Cliff Feiman; Dana Licata; Dana Smart; Dawn Reynolds; [email protected]; Elliot Kendall; Elyssa Perez; Frank Dattoma; Frank Perez; Fumiko Wakabayashi; Giancarlo Sciama; Guillevermo Vega; Harry Weinger; Helena Riordan; Jane Komarov; Jason Pastori; Jeffrey Glixman; Jerry Stine; Jessica Connor; Jim Dobbe; JoAnn Frederick; Joe Black; John Gruhler; Jyl Forgey; Karen Sherlock; Kelly Martinez; Kerri Sullivan; Kim Henck; Kristen Burke; Laura Weigand; Lee Lodyga; Leonard Kunicki; Lori Froeling; Lorie Slater; Maggie Agard; Marcie Turner; Margaret Goldfarb; Mark Glithero; Mark Loewinger; Martin Wada; Melanie Crowe; Michael Kachko; Michelle Debique; Nancy Jangaard; Norma Wilder; Olly Lester; Patte Medina; Paul Reidy; Pete Hill; Ramon Galbert; Randy Williams; Robin Kirby; Ryan Gamsby; Ryan Null; Sarah Norris; Scott Ravine; Shelin Wing; Silvia Montello; Simon Edwards; Stacy Darrow; Stan Roche; Steve Heldt; Sujata Murthy; Todd Douglas; Todd Nakamine; Tracey Hoskin; Wendy Bolger; Wendy Tinder; Werner Wiens ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The Complete A&M Years CD #: B0000348-02 UPC #: 6 069 493 683-2 CD Logo: A&M Records & Chronicles Attached please find all necessary liner notes and credits for this package. Beth Dennis Brown – Complete A&M Years B0000348-02 1 12/01/19 11:49 AM Dennis Brown The Complete A&M Years (CD Booklet) Original liner notes from The Prophet Rides Again This album is dedicated to the Prophet Gad (Dr. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

The Funky Diaspora

The Funky Diaspora: The Diffusion of Soul and Funk Music across The Caribbean and Latin America Thomas Fawcett XXVII Annual ILLASA Student Conference Feb. 1-3, 2007 Introduction In 1972, a British band made up of nine West Indian immigrants recorded a funk song infused with Caribbean percussion called “The Message.” The band was Cymande, whose members were born in Jamaica, Guyana, and St. Vincent before moving to England between 1958 and 1970.1 In 1973, a year after Cymande recorded “The Message,” the song was reworked by a Panamanian funk band called Los Fabulosos Festivales. The Festivales titled their fuzzed-out, guitar-heavy version “El Mensaje.” A year later the song was covered again, this time slowed down to a crawl and set to a reggae beat and performed by Jamaican singer Tinga Stewart. This example places soul and funk music in a global context and shows that songs were remade, reworked and reinvented across the African diaspora. It also raises issues of migration, language and the power of music to connect distinct communities of the African diaspora. Soul and funk music of the 1960s and 1970s is widely seen as belonging strictly in a U.S. context. This paper will argue that soul and funk music was actually a transnational and multilingual phenomenon that disseminated across Latin America, the Caribbean and beyond. Soul and funk was copied and reinvented in a wide array of Latin American and Caribbean countries including Brazil, Panama, Jamaica, Belize, Peru and the Bahamas. This paper will focus on the music of the U.S., Brazil, Panama and Jamaica while highlighting the political consciousness of soul and funk music. -

Various Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends Country: UK Released: 1990 Style: Roots Reggae, Dub, Rocksteady MP3 version RAR size: 1668 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1377 mb WMA version RAR size: 1298 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 963 Other Formats: AIFF AC3 AUD AAC MP3 MPC FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits My Conversation A1 –Slim Smith And The Uniques Written-By – K. Smith* 100,000 Dollars A2 –The Success All Stars Written-By – Rupie Edwards Doctor Come Quick A3 –Hugh Roy Junior* Written-By – Hugh Roy Jnr.* Half Way Tree Pressure A4 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson Mi Nuh Matta A5 –El Cisco Delgado Written-By – Delgado* Tribute To Slim Smith A6 –Tyrone Downie Written-By – Downie* Doctor Satan Echo Chamber A7 –The Success All Stars Written-By – Rupie Edwards Yamaha Skank A8 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson Riding With Mr. Lee B1 –Earl "Chinna" Smith Written-By – Earl "China" Smith* President A Mash Up The Resident B2 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson President Rock B3 –Joe White Written-By – J. White* Dew Of Herman B4 –Bongo Herman & Les* Written-By – Bongo Herman, Les* Give Me The Right B5 –The Heptones Written-By – Unknown Artist Underworld Way B6 –Shorty The President Written-By – Rupie Edwards Christmas Rock B7 –Rupie Edwards Written-By – Rupie Edwards Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Trojan Records Copyright (c) – Trojan Records Marketed By – Trojan Sales Ltd. Pressed By – Adrenalin Mastered At – PRT Studios Credits Design – Steve Barrow, Steve Lane Liner Notes – Steve Barrow Producer – Rupie Edwards (tracks: A2 - A8, B1 - B7) Producer [uncredited] – Bunny Lee (tracks: A1) Remastered By – Malcolm Davies Notes Digitally remastered issue of "Yamaha Skank" with additional tracks. -

14,99€ 9,99€ 17,99€ 20,99€ 21,99€ 19,99€

IRIE RECORDS GMBH IRIE RECORDS GMBH NEW RELEASE CATALOGUE NO. 398 RINSCHEWEG 26 (CD/LP/10"&12"/7") 48159 MUENSTER (23.08.2015 - 12.09.2015) GERMANY TEL. +49-(0)251-45106 HOMEPAGE: www.irie-records.de MANAGING DIRECTOR: K.E. WEISS EMAIL: [email protected] REG. OFFICE: MUENSTER/HRB 3638 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ IRIE RECORDS GMBH: DISTRIBUTION - WHOLESALE - RETAIL - MAIL ORDER - SHOP - YOUR SPECIALIST IN REGGAE & SKA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- OPENING HOURS: MONDAY/TUESDAY/WEDNESDAY/THURSDAY/FRIDAY 13 – 19; SATURDAY 12 – 16 CD CD CD JAPAN IMPORT CD 2CD CD 9,99€ 17,99€ 18,99€ 16,99€ 1)19,99€ 17,99€ 1) 16,99€ 14,99€ 1) 16,99€ CD CD CD CD CD CD 14,99€ 9,99€ 17,99€ 20,99€ 21,99€ 19,99€ 1) PLEASE NOTE: SPECIAL SALE PRICE ONLY VALID FOR ORDERS RECEIVED UNTIL OCTOBER 15th 2015! IRIE RECORDS GMBH NEW RELEASE-CATALOGUE 09/2015 PAGE 2 *** CDs *** CD CD CD CD CD CD 11,99€ 18,99€ 16,99€ 19,99€ 20,99€ 18,99€ ALDUBB............................ A TIMESCALE OF CREATION....... ONE DROP....... (GER) (15/15). 14.99EUR ALDUBB............................ ADVANCED PHYSICS.............. ONE DROP....... (GER) (08/08).. 9.99EUR ERROL BELLOT...................... KNOW JAH (11 VOC & 5 DUBS).... REALITY SHOCK.. (GBR) (11/12). 17.99EUR BLAAK LUNG (feat. BATCH/LUTAN FYAH/RAS ATTITUDE/MALIKA MADREMANA/MAHAD MAHAN).....(@ sale price now!)... ASPIRE (V.I. ROOTS)........... GREEN SPHERE... (USA) (08/08).. 9.99EUR BLACK HEAT DUB.................... GREATEST DUB HITS............. GOLDENLANE..... (GER) (--/11). 17.99EUR RICHIE CAMPBELL................... IN THE 876.................... BRIDGETOWN..... (POR) (15/15). 17.99EUR DON FE............................ I-VOLUTION.................... ORGANIC ROOTS. -

Tony Chin Earl Zero Derrick Lara Papa Michigan Johnny Dread Anthony John Fully Fulwood Mellow Movement Iriemag.Com

DEC 2015 CA 01.04 T R A X ROOTS / ROCK / REGGAE / RESPECT featuring HOUSE OF SHEM ARMY RAS D Z-MAN TONY CHIN EARL ZERO DERRICK LARA PAPA MICHIGAN JOHNNY DREAD ANTHONY JOHN FULLY FULWOOD MELLOW MOVEMENT IRIEMAG.COM CA ISSUE #01.04 / DECEMBER 2015 “ If you haven’t confidence in self, you are twice defeated in the race of life. With confidence, you have won even before you have started.” - Marcus Garvey Nicholas ‘Nico’ Da Silva Founder/Publisher & Editor in Chief IRIEMAG.COM MERCH. The Official ‘Rockers’ Tee from Irie Magazine Available in T-Shirts & Hoodies for Men/Women Two styles to choose from: Jamaica or Ethiopia IRIEMAG.COM House of Shem Derrick Lara Papa Michigan Ras D New Zealand Jamaica Jamaica Jamaica Army Fully Fulwood Tony Chin Johnny Dread U.S. Virgin Islands Jamaica Jamaica United States Earl Zero Anthony John Mellow Movement Z-Man United States Jamaica United States United States NZL HOUSE OF SHEM IRIEMAG.COM REGGAE HOUSE OF SHEM House Of Shem is an Aotearoa (New Zealand) based harmony trio comprised of Carl Perkins and his FOLLOW two sons, Te Omeka Perkins and Isaiah Perkins, who are each multi-instrumentalist and producers. House of Shem Formed 2005 in the rural area of Whanganui, the band embodies elements of roots reggae, pacific reggae and traditional maori music with relatable song-writing that connects powerfully with not only New Zealand and Australia audiences, but reggae listeners globally attracting fans from all Featured Album areas of the world. Since bursting onto the music scene with their debut album ‘Keep Rising’ in 2008, House of Shem has released three very successful Albums and built a rapidly growing loyal fan base. -

Rupie Edwards Ire Feelings (Skanga) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Rupie Edwards Ire Feelings (Skanga) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Ire Feelings (Skanga) Country: UK Released: 1974 Style: Dub MP3 version RAR size: 1341 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1176 mb WMA version RAR size: 1168 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 609 Other Formats: AU RA DMF AAC AIFF MP4 FLAC Tracklist A –Rupie Edwards Ire Feelings (Skanga) B –Rupie Edwards All Stars Feeling High Credits Producer – Rupie Edwards Written-By – R. Edwards* Notes White labels with black print, CACTUS at the top in a sans serif typeface, without Cactus label logo. This is a label variation and not a promo. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Ire Feelings (7", CT 38 Rupie Edwards Cactus CT 38 UK 1974 Single) Ire Feelings (Skanga) 13791 Rupie Edwards Eurodisc 13791 France 1975 (7") 6C 006-96250 Rupie Edwards Ire Feelings (7") EMI 6C 006-96250 Denmark 1974 none Rupie Edwards Ire Feeling (7") Success none Jamaica Unknown Ire Feelings (Skanga) CT 38 Rupie Edwards Cactus CT 38 UK 1974 (7", Single) Related Music albums to Ire Feelings (Skanga) by Rupie Edwards Rupie Edwards All Stars / Joe White - My Piano And I / Tell Me Rupie Edwards, The Virtues / The Virtues - Falling In Love / Sweet Nanny Rupie Edwards - Rupies Gems Chapter II Dobby Dobson - Endlessly Rupie Edwards - Sweet Gospel Volume Four Various - Reggae Chartbusters 75 Various - Rupie's Scorchers Shorty The President / Rupie Edwards All Stars - Yamaha Way (Yamaha Skank) / I A No Want Stall Version Rupie Edwards All Stars - Music Alone Shall Live Rupie Edwards / Noel Bailey - Oh Black People / It's Time To Be Free The African Brothers / Rupie Edwards - Mystry Of Nature / I'm Gonna Live Some Life tommy edwards -. -

Various Listen Up! Rocksteady Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Listen Up! Rocksteady mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Listen Up! Rocksteady Country: UK Released: 2012 Style: Rocksteady MP3 version RAR size: 1329 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1792 mb WMA version RAR size: 1783 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 439 Other Formats: TTA AUD MPC APE MIDI VQF VOC Tracklist A1 –The Uniques People Rocksteady A2 –Roy Shirley & Glen Adams Musical Train A3 –The Uniques My Conversation A4 –The Sensations Long Time Me No See You Girl A5 –Pat Kelly Daddy's Home A6 –Dawn Penn I'll Get You A7 –The Uniques The Beatitude B1 –Slim Smith Love & Devotion B2 –Delroy Wilson Till I Die B3 –Roy Shirley Dance Arena B4 –Glen Adams Run Come Dance B5 –Winston Samuels It's Been So Long B6 –Ann Reid Remember When B7 –Roy Shirley Touch Them (Never Let Them Go) Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year KSCD033 Various Listen Up! Rocksteady (CD, Comp) Kingston Sounds KSCD033 UK 2012 Related Music albums to Listen Up! Rocksteady by Various The Uniques - Golden Hits Slim Smith - My Conversation Various - Studio One Rocksteady (Rocksteady, Soul And Early Reggae At Studio One) Glen Adams / Peter Tosh - Cat Woman / Selassie Serenade Roy Shirley - I'm The Winner Delroy Wilson - Dancing Mood Various - Reggae Going International 1967-1976: 22 Hits From Bunny 'Striker' Lee The Uniques - Every Now And Then (I Cry) / Love Is A Precious Thing Slim Smith - Womans Love / Give Me A Love The Uniques / Slim Smith - Girl Of My Dreams / Love Power The Uniques - Uniquely Yours Roy Shirley, Stranger Cole, Ken Parker - Rock Steady Greats (Get In The Groove). -

7” SINGLES SALE LIST No.1

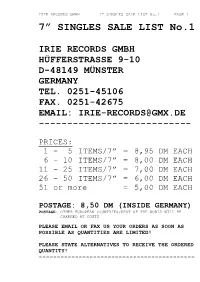

IRIE RECORDS GMBH 7“ SINGLES SALE LIST No.1 PAGE 1 7” SINGLES SALE LIST No.1 IRIE RECORDS GMBH HÜFFERSTRASSE 9-10 D-48149 MÜNSTER GERMANY TEL. 0251-45106 FAX. 0251-42675 EMAIL: [email protected] --------------------------- PRICES: 1 - 5 ITEMS/7” = 8,95 DM EACH 6 - 10 ITEMS/7” = 8,00 DM EACH 11 - 25 ITEMS/7” = 7,00 DM EACH 26 - 50 ITEMS/7” = 6,00 DM EACH 51 or more = 5,00 DM EACH POSTAGE: 8,50 DM (INSIDE GERMANY) POSTAGE: OTHER EUROPEAN COUNTRIES/REST OF THE WORLD WILL BE CHARGED AT COSTS PLEASE EMAIL OR FAX US YOUR ORDERS AS SOON AS POSSIBLE AS QUANTITIES ARE LIMITED! PLEASE STATE ALTERNATIVES TO RECEIVE THE ORDERED QUANTITY! ------------------------------------------- IRIE RECORDS GMBH 7“ SINGLES SALE LIST No.1 PAGE 2 ABUI PRODUCTION NEW PRODUCT – SHOULD I/TREMOR VERSION MAJOR STONE – MASH THEM CORN/TREMOR VERSION MEEKIE MELODY – STRANGE/DISNEY WORLD VERSION CLIVE MEDIA – SORRY FI HAR/VIBES VERSION CLIVE MEDIA – MAN A KILL MAN/VISION VERSION AFC U-4-I-A – UNTIL I GET YOU BACK/GET YOU BACK MIX 2 AFRICAN MUSEUM TONY BREVETT – BRIGHT STAR/SHOOT ON SIGHT E.Q. – BE WITH YOU/VERSION JAH GUAYA – KEEP THE SABATH HOLY/VERSION MELODIANS – BRIGHT STAR/VERSION AFRICAN STAR MIKAL ASHER – ORIGINAL BINGIE/VERSION GRANTY ROOTS – MAMA OMEGA/VERSION MAGANOE – WHAT’S ANOTHER DAY/VERSION AFRO DEZIAC DETERMINE/J. KELLY – HANDS IN DI AIR/HOW COME, HOW LONG AKSHON HOUSE CALLALOO MAN – MAMA FIRST BORN/VERSION COLONEL LLOYDIE – DEM-A-CRY/VERSION GONZALIS – NAH NYAM/VERSION STEVE MACHETE – WOLF/VERSION ALSENCERE – BABYLON WORLD/VERSION ALFOMEGA PRINCE THEO – -

IRIE RECORDS New Release Catalogue 06-10

IRIE RECORDS GMBH IRIE RECORDS GMBH BANKVERBINDUNG: EINZELHANDEL NEUHEITEN-KATALOG NR. 289 RINSCHEWEG 26 IRIE RECORDS GMBH (CD/LP/10"&12"/7") 48159 MÜNSTER KONTO NR. 35 60 55, (VOM 01.06.2010 BIS 25.06.2010) GERMANY BLZ 400 501 50 TEL. 0251-45106 SPARKASSE MÜNSTERLAND OST SCHUTZGEBÜHR: 0,50 EUR (+ PORTO) EMAIL: [email protected] HOMEPAGE: www.irie-records.de GESCHÄFTSFÜHRER: K.E. WEISS/SITZ: MÜNSTER/HRB 3638 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ IRIE RECORDS GMBH: DISTRIBUTION - WHOLESALE - RETAIL - MAIL ORDER - SHOP - YOUR SPECIALIST IN REGGAE & SKA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- GESCHÄFTSZEITEN: MONTAG/DIENSTAG/MITTWOCH/DONNERSTAG/FREITAG 13 – 19 UHR; SAMSTAG 12 – 16 UHR ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CD CD CD CD CD CD 1) 1) CD CD CD CD CD CD 1) PLEASE NOTE: SPECIAL SALE PRICE ONLY VALID FOR ORDERS RECEIVED UNTIL 05.07.2010! IRIE RECORDS GMBH NEW RELEASE-CATALOGUE 06/2010 SEITE 2 *** CDs *** YASUS AFARI....................... REVOLUTION CHAPTER 1.......... SENYA-CUM...... (JAM) (07/07). 17.99EUR HORACE ANDY....................... SERIOUS TIMES (15 NEW TRAX!).. MINOR 7 FLAT 5. (GER) (10/10). 16.99EUR CAPLETON.......................... I-TERNAL FIRE (15 NEW TRAX!).. VP/CAPLETON MUS (USA) (10/10). 16.99EUR CLINTON FEARON.................... MI DEH YAH.................... MAKASOUND/MAKAF (FRA) (10/10). 17.49EUR FLEXATONES (feat. EARL 16/MOLARA/NICO WILLIS & PAPA ZAI/MOMO CAT & HOSNI/NATTY FRUITS/PUPPA J/ MOMO CAT/NATTY KAUKA/HOSNI)...... ORIGINALS (+ 7 DUBS).......... FAT BELT....... (FIN) (07/07). 18.99EUR GENTLEMAN (feat. SUGAR MINOTT/PATRICE/ TANYA STEPHENS/JACK RADICS & LUCIANO/CHRISTOPHER MARTIN/ REBELLION THE RECALLER/ANTHONY RED ROSE/CASSANDRA STEEN/ PROFESSOR/MILLION STYLEZ)........ DIVERSITY (2CD DELUXE EDITION) ISLAND......... (GER) (10/10). 19.99EUR 2CD MATO.............................