Reconceiving the Motherhood Mandate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record 63 Independent Pilots Selected for the 12Th

Press Note – please find assets at the below links: Photos – https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B-lTENXjpYxaWmEtRTIzSVozcFU Trailers – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLIUPrhfxAzsCs0VylfwQ-PEtiGDoQIKOT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RECORD 63 INDEPENDENT PILOTS SELECTED FOR THE 12TH ANNUAL NEW YORK TELEVISION FESTIVAL *** As Official Artists, Creators will Enjoy Opportunities with Network, Digital, Agency and Studio execs at October TV Fest Independent Pilot Competition Official Selections to be Screened for the Public from October 24-29, Including 42 World Festival Premieres [NEW YORK, NY, August 15, 2016] – The NYTVF (www.nytvf.com) today announced the Official Selections for its flagship Independent Pilot Competition (IPC). A record-high 63 original television and digital pilots and series will be presented for industry executives and TV fans at the 12th Annual New York Television Festival, including 42 world festival premieres, October 24-29, 2016 at The Helen Mills Theater and Event Space, with additional Festival events at the Tribeca Three Sixty° and SVA Theatre. The slate of in-competition projects was selected from the NYTVF's largest pool of pilot submissions ever: up more than 42 percent from the previous high. Festival organizers also noted that the selections are representative of creative voices across diverse demographics, with 59 percent having a woman in a core creative role (creator, writer, director and/or executive producer) and 43 percent including one or more persons of color above the line (core creative team and/or lead actor). “We were blown away by the talent and creativity of this year's submissions – across the board it was a record-setting year and we had an extremely difficult task in identifying the competition slate. -

25 Days of Christmas

Saturday, December 6 Thursday, December 11 7 AM All I Want For Christmas 5 PM Jack Frost (1998) 9 PM A Dennis The Menace Christmas 7 PM Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation 11 AM Fred Claus 9 PM Scrooged 1:30 PM Frosty’s Winter Wonderland 12 AM The Mistle-tones 2 PM The Santa Clause 3: Escape Friday, December 12 Clause 4:30 PM Jack Frost (1979) 4 PM How The Grinch Stole Christmas 5:30 PM Scrooged 6:30 PM Toy Story 3 7:30 PM The Santa Clause Sunday, December 7 9:30 PM Miracle On 34th Street (1994) 7 AM Dennis The Menace Christmas 12 AM Holiday In Handcuffs 9 AM The Little Drummer Boy Saturday, December 13 9:30 AM Rudolph & Frosty’s Christmas In 7 AM Unlikely Angel July 9 AM The Mistle-tones Monday, December 1 11:30 AM Arthur Christmas 11 AM Home Alone 3 4 PM Jack Frost (1979) 1:30 PM Jack Frost (1998) 1 PM Prancer 5 PM Santa Claus Is Comin' To Town 3:30 PM The Santa Clause 3: The Escape 3 PM Miracle On 34th Street (1994) 6 PM Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation Clause 5:30 PM Mickey’s Christmas Carol 8 PM Elf 5:30 PM Toy Story 3 6 PM The Santa Clause 10 PM The Santa Clause 8 PM Toy Story That Time Forgot 8 PM Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation Tuesday, December 2 8:30 PM Elf 10 PM Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town 4 PM Rudolph & Frosty’s Christmas In July Monday, December 8 Sunday, December 14 6 PM Elf 5 PM The Year Without Santa Claus 7 AM Miracle On 34th Street (1994) 8 PM The Santa Clause 6 PM Elf 9:30 AM Disney’s A Christmas Carol 10 PM The Santa Clause 3: The Escape Clause 8 PM The Fosters 11:30 AM Jack Frost (1998) 12 AM Prancer 9 PM Switched At Birth 1:30 -

ROSE ABDOO Theatrical Resume

ROSE ABDOO Page 1 of 3 ROSE ABDOO MOW MEDDLING MOM Hallmark Dir: Patricia Cardoso FILM YELLOW DAY Independent Dir: Carl Lauten THE GUILT TRIP Paramount Studios Dir: Anne Fletcher BAD TEACHER Columbia Pictures Dir: Jake Kasdan GOOD NIGHT & GOOD LUCK Warner Independent Dir: George Clooney LEGALLY BLONDE 3 MGM Dir: Savage Steve Holland RELATIVE STRANGERS Independent Dir: Greg Glienna 40 YEAR OLD VIRGIN Universal Dir: Judd Apatow SOMEONE TO EAT CHEESE WITH Independent Dir: Jeff Garlin MY BEST FRIEND'S WEDDING Touchstone Dir: P.J. Hogan UNCONDITIONAL LOVE New Line Cinema Dir: P.J. Hogan U.S. MARSHALL Warner Bros. Dir: Stuart Baird VANILLA CITY Independent Dir: Reid Brody TELEVISION The Mentalist Guest Star CBS Baby Daddy Guest Star ABC Family FAMILY TOOLS Co-Star ABC SHAMELESS Guest Star Showtime PARENTHOOD Guest Star NBC PSYCH Guest Star USA BUNHEADS Recurring Guest Star ABC Family TWO BROKE GIRLS Guest Star CBS PRETTY LITTLE LIARS Guest Star ABC Family THE DAMN THORPES Recurring CW Pilot GOOD LUCK CHARLIE Guest Star Disney Channel BROTHERS & SISTERS Guest Star ABC CSI: NY Guest Star CBS CURB YOUR ENTHUSIASM Guest Star HBO WITHOUT A TRACE Guest Star CBS MONK Guest Star USA WIZARDS OF WAVERLY PLACE Guest Star Disney Channel GILMORE GIRLS Recurring CW THAT'S SO RAVEN Recurring Disney Channel THE RETURN OF JEZEBEL JAMES Recurring FOX Pilot NURSES Recurring FOX Pilot THE WAR AT HOME Guest Star FOX IN CASE OF EMERGENCY Guest Star ABC INCONCEIVABLE Guest Star NBC GRAND UNION Recurring NBC Pilot MALCOM IN THE MIDDLE Guest Star FOX DR. VEGAS Guest -

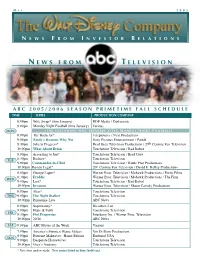

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

Baby Daddy: a Family Business

SEPTEMBER 2013 Baby Daddy: A Family Business . (ABC FAMILY/ANDREW ECCLES) ED V RESER RIGHTS LL . A NC , I NTERPRISES E ISNEY © 2012 D ABC Family’s Baby Daddy stars Chelsea Kane as Riley, Derek Theler as Danny, Jean-Luc Bilodeau as Ben, twins Ali and Susanne Hartman as Emma, Melissa Peterman as Bonnie and Tahj Mowry as Tucker. By Marissa Berlin 5:00 PM — It’s a Friday evening, and a line What Baby Daddy shares with such revered clan means they also have a lot of love for of smiling fans shuffles in to Stage 20. Most comedies as Seinfeld, Will & Grace, and The the Baby Daddy Family as a whole. think they’re here to simply see a show, but Mary Tyler Moore Show goes beyond its multi- those colored wristbands they’re wearing camera format (or where it’s shot!). In its Created by Executive Producer Dan have just made them an integral part of the respective decade, each of these shows Berendsen (The Nine Lives of Chloe King, larger Baby Daddy “Family” – a dedicated became a hit because it reflected America Sabrina the Teenage Witch) and directed by group of people who all contribute to the through the antics of its on-screen family. Michael Lembeck (Friends, Mad About You) success of the show. And that’s not all: in Whether it was a group of friends, a herd of Baby Daddy is the story of Ben Wheeler (Jean- laughing along with a live taping here at workplace colleagues, or an actual family… Luc Bilodeau) becoming a surprise father CBS Radford, this audience will also join the on-screen cast was only a part of that to a baby girl left on his doorstep by an ex- a continuum of sitcom families among the larger Family. -

Terry O'bright

Various Sound Credits 2005 - 2014 Our teams of sound designers and editors have won more Emmys (16), Golden Reels (35) and other recognition for quality than any other sound company! 2014 Whitney (Cable Movie - Lifetime/A&E) - Full sound & mixing package 2014 Person of Interest (TV series - CBC) - Mixing package 2014 Flash (TV series - CW) - Mixing package 2014 NCIS (TV Series - CBS) - Full sound & mixing package 2014 NCIS: New Orleans (TV Series - CBS) - Full sound & mixing package 2014 Cosmos (TV Series - Fox) - Full sound & mixing package *2014 EMMY winner - best Sound Effects Editorial 2014 Scorpion (TV series - CBC) - Mixing package 2014 Tyrant (TV series - FX) - Mixing package & M&E package 2014 Perception (TV series - ABC) - ADR & Mixing package 2014 Drum Line (Cable Movie - VH1) - Full sound & mixing package 2014 Crossbones (TV Series - NBC) - Full sound & mixing package 2014 The Divide (TV Series - WE TV) - Full sound & mixing package 2014 Petals on the Wind (Cable Movie) - Full sound & mixing package 2014 Return to Zero (Cable Movie - Lifetime) - Full sound & mixing package 2011-14 Falling Skies (Cable series - TNT/Dreamworks) Full sound & mixing package 2009-14 Modern Family (TV series - Fox for ABC) - Full sound & mixing package *2010 & 2012 EMMY winner - best Mixing / 2014 CAS award - Best Mixing 2008-14 Sons of Anarchy (Cable series - FX/Fox) – Full sound & mixing package *2014 Golden Reel Award - best Sound Editorial 2010-14 The Good Wife (TV series - Fox) – Mixing package 2008-14 Bones (TV series - Fox) – Mixing package -

About the Mcdonaldscruelty.Com Celebrity TV Ad

About the Celebrity Cast − Emily Deschanel (Bones) McDonaldsCruelty.com − James Cromwell (Jurassic World, L.A. Confidential, Babe) − Daisy Fuentes (Model, TV Host) Celebrity TV Ad − John Salley (NBA Basketball Champion) − Moby (Musician, DJ) − Alison Pill (Star Trek, The Newsroom, Vice) − Daniella Monet (Victorious, Baby Daddy, Ariana Grande: Thank U, Next) − Matt Lauria (Friday Night Lights, Kingdom, Parenthood) Days before McDonald’s annual shareholder meeting on May − Kimberly Elise (John Q, The Manchurian Candidate, Star) 23, a cast of 25 celebrities are urging the company in a new TV − Joshua Leonard (Unsane, Scorpion, The Blair Witch Project) ad to adopt a comprehensive chicken welfare policy. The cast − Emma Kenney (Shameless, The Connors) includes Moby, Emily Deschanel, James Cromwell, Kimberly − Alexandra Paul (Baywatch, Christine, Dragnet) Elise, Matt Lauria, Joanna Krupa, Daisy Fuentes, John Salley, − Devon Werkheiser (Ned’s Declassified School Guide, Crown Vic, Greek) and Alison Pill. (full list right) − Stephanie Corneliussen (Mr. Robot, Legion) − Rick Cosnett (The Flash, The Vampire Diaries, Quantico) Late last year, Alec Baldwin, Kristen Bell, Susan Sarandon, − James Kyson (Heroes, Walk to Vegas) Joaquin Phoenix, and more than 15 other celebrities also called − Allison Scagliotti (Stitchers, The Vampire Diaries, Warehouse 13) on McDonald’s to change its animal welfare standards. − Josh Zuckerman (90210, Desperate Housewives) − Mark Hapka (Days of Our Lives, Ghost Whisperer) The new TV ad, produced by Mercy For Animals, will air − Joanna Krupa (Dancing with the Stars, The Real Housewives of Miami) for two weeks in the Chicago media market (McDonald’s is − Kelley Jakle (Pitch Perfect, Pitch Perfect 2, Pitch Perfect 3) headquartered in Chicago). -

By % EPISODES DIRECTED by FEMALES & MINORITIES

2016 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by % EPISODES DIRECTED BY FEMALES & MINORITIES) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Male # Episodes Female Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Directed by Female Title Female + Caucasian Directed by Caucasian Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Minority % Female Female Minority % Minority % % Male Minority % Episodes Caucasian Caucasian Minority 11/22/63 9 0 0% 9 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% NS Pictures, Inc. Hulu Plus Almost There We're Out of Time DirecTV 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Productions Inc. Aquarius 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Next Step Productions LLC NBC Ash vs. Evil Dead 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Starz Evil Productions, LLC Starz! Baby Daddy 20 0 0% 20 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Prodco, Inc. ABC Family Baskets 9 0 0% 9 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Louie Zach Productions, Inc. FX Benders 8 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Blink TV, LLC IFC Berlin Station Paramount Overseas Epix 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Productions, Inc. Black Jesus 11 0 0% 11 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Triage Entertainment, LLC Cartoon Network Blunt Talk Right Here Right Now Starz! 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Productons, LLC Clipped Horizon Scripted Television TBS 9 0 0% 9 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Inc. CSI: Crime Scene CBS Broadcasting Inc. -

Wednesday Morning, Aug. 28

WEDNESDAY MORNING, AUG. 28 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Chuck Nice and Rachel Live! With Kelly and Michael (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Campos-Duffy. (cc) (TV14) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today (N) (cc) The Jeff Probst Show Rainn Wil- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) son; Yvette Nicole Brown. (TV14) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! Cin- Dinosaur Train Sesame Street The A Team. Big A Daniel Tiger’s Sid the Science WordWorld (TVY) Barney & Friends 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot derella. (TVY) (TVY) looks for members. (TVY) Neighborhood Kid (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Paid Better Summer beauty products; 12/KPTV 12 12 leather. (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible International Fel- Paid Paid Paid Paid Married. With Pay It Forward 22/KPXG 5 5 lowship Children (TVPG) ★★ (‘00) (2:02) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Joseph Prince This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Alive With Kong Against All Odds Pro-Claim Behind the Joyce Meyer Life Today With Today With Mari- 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (TVG) Scenes (cc) James Robison lyn & Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) The Steve Wilkos Show A woman The Bill Cunningham Show Cheat- Jerry Springer Couples have The Steve Wilkos Show A box con- 32/KRCW 3 3 accuses a man of rape. -

Casting Offices Audition/Called Me in (BOLD = Booked, Italic = PINNED, * = Callback Last Time I Saw Them BOOKED (Bold) / AVAIL (Italic)

Casting Offices Audition/Called me in (BOLD = Booked, Italic = PINNED, * = callback Last Time I Saw Them BOOKED (Bold) / AVAIL (Italic) FIRST TIER The Fincannons (ATL) 11 (H&F x3, H&F*, Red State Society, Ebb Tide, Duty, Nashville, FWD, DM, Six) Six audition 5/18/16 DEVIOUS MAIDS McCarthy/Abellera 10 (Mindy Project x3, Silicon Valley x4, ACS, Grinder, LOPEZ) Lopez booking 2/19/16 LOPEZ Feldstein/Paris (ATL) 10 (Fundamentals*, Atlanta x2, SURVIVOR'S REMORSE, Ozark, etc) Ozark audition 6/17/16 SURVIVOR'S REMORSE Dava Waite Peaslee 8 (Weeds, RAISING HOPE, The Millers x2, The Millers, Crowded x2, Good Fortune) Good Fortune audition 3/1/16 RAISING HOPE, The Millers Geraldine Leder Six (Assistance, DADS, Dads, Bad Judge x3) BAD JUDGE audition 10/16/14 Dads Alyson Silverberg Five (GEOGRAPHY CLUB, Baby Daddy, Faking It, Mystery Girls, Jane the Virgin) Jane the Virgin audition 2/11/16 GEOGRAPHY CLUB CFB Casting Five (NEWSREADERS, NEW GIRL, Ben & Kate X2, Trophy Wife) AK workshop 8/4/13 w/ Melanie NEWSREADERS, NEW GIRL Cara Chute Four (THE WHY, IMPRESSIONS, YPF x2) Youth Playwrights Festival audition 4/26/16 THE WHY (Play), IMPRESSIONS (Short) Josh Einsohn Four (DUTY, Marry Me x2, UNTITLED CHRIS CASE PILOT) UNTITLED CHRIS CASE pilot 3/7/16 Duty Wendy O'Brien Four (LEGIT, Family Tools, You're the Worst, ANGIE TRIBECA) Angie Tribeca booking 12/8/15 LEGIT, ANGIE TRIBECA Krisha Bullock Three (VICTORIOUS, Sam & Kat, Game Shakers) Game Shakers audition 6/14/16 VICTORIOUS Jeremy Gordon Three (My Synthesized Life, SONS OF THE DEVIL, Parental Advisory) Parental Advisory audition 10/25/15 SONS OF THE DEVIL (Short) Stiner/Block Three (Who's Your Monster?, Good Luck Charlie, Kirky Buckets) KIRBY BUCKETS audition 6/26/14 Good Luck Charlie Lindsay Chag Three (HOLLY'S HOLIDAY, AGVN The Movie, Naughty or Nice) AK Workshop 9/18/13 HOLLY'S HOLIDAY Mark Sikes Twice (DAWN OF THE CRESCENT MOON, Loyalty) BHP workshop 10/5/13 DAWN OF THE CRESCENT MOON Sitowitz/Pianko Twice (TruTV, INCREDIBLE CREW) BHP Workshop 6/9/13 INCREDIBLE CREW, TruTV (commercial) Angela M. -

City Court Hears Criminal Docket for August Cases

HHERALDING OOVER A CCENTURY OF NNEWS CCOVERAGE •• 1903-20131903-2013 LIFESTYLES INSIDE SPORTS JACKSON CASHWORD DEMONS SQUARE ARENA WINNERS BOXING SHARE $400 WIN! See Page 1B See Page 3A See Page 8A The Natchitoches Times And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free, John 8:32. Weekend Edition, August 31-September 1, 2013 Natchitoches, Louisiana • Since 1714 Seventy-Five Cents the Copy Letters to the Editor Let us know what you think, City court hears write a letter to the editor. See Page 4A for details. Natchitoches Times e-mail [email protected] criminal docket Visit our website at: www.natchitochestimes.com for August cases WEATHER The following cases came Schuyler Wayne Davis Jr., HIGH LOW before Judge Fred Gahagan in theft by shoplifting, reset Feb. 100 71 City Court Aug. 5: 10, diversion. Leah Admire, theft by Chasman Evans, aggravat- shoplifting, pleaded guilty, ed assault, BW failure to Area Deaths sentence of the court was, appear. confine 120 days in jail, credit Emily Firmin, theft by Gladys Marie Sims toward time served. shoplifting, remaining on Robert Earl Freeman Jr. Donivan Boast, theft by premises, pleaded not guilty, shoplifting, pleaded guilty, trial Sept. 9. Obituaries Page 2A sentence of the court was, Carnealus Gay, loud music The dedication of Caspari Hall and Student Services Center, at right, will be at 2 pm. confine 60 days in jail, 60 days amended disturbing the Wednesday, Sept. 4. in jail suspended, one year peace, cash bond forfeited. NPD to offer supervised probation, pay fine Jade Grayson, theft by and cost totaling $431, default shoplifting, reset Nov. -

2013 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By % of EPISODES DIRECTED by MINORITIES)

2013 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by % of EPISODES DIRECTED BY MINORITIES) Title Total # of # Episodes Minority # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Signatory Company Network Episodes Directed by % Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Minorities Male % Male % Female % Female % Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority After Lately 8 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% CP Entertainment Services, LLC E! Americans, The 12 0 0% 10 83% 0 0% 2 17% 0 0% TVM Productions, Inc. FX Bates Motel 10 0 0% 9 90% 0 0% 1 10% 0 0% NBC Studios LLC A&E Beauty & the Beast 20 0 0% 17 85% 0 0% 3 15% 0 0% BATB Productions Inc CW Big C, The 14 0 0% 9 64% 0 0% 5 36% 0 0% Remote Broadcasting, Inc. Showtime Boardwalk Empire 12 0 0% 11 92% 0 0% 1 8% 0 0% Home Box Office, Inc. HBO Breaking Bad 16 0 0% 12 75% 0 0% 4 25% 0 0% Topanga Productions, Inc. AMC Devious Maids 12 0 0% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% ABC Studios Lifetime Enlightened 8 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 1 13% 0 0% Home Box Office, Inc. HBO Exes, The 12 0 0% 12 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% King Street Productions Inc. TV Land Falling Skies 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Turner North Center Productions, Inc. TNT Friend Me 7 0 0% 6 86% 0 0% 1 14% 0 0% Eye Productions Inc.