Educating for Civic Reasoning and Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21St Century

An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. Robison Margaret Weigel Building the new field of digital media and learning The MacArthur Foundation launched its five-year, $50 million digital media and learning initiative in 2006 to help determine how digital technologies are changing the way young people learn, play, socialize, and participate in civic life.Answers are critical to developing educational and other social institutions that can meet the needs of this and future generations. The initiative is both marshaling what it is already known about the field and seeding innovation for continued growth. For more information, visit www.digitallearning.macfound.org.To engage in conversations about these projects and the field of digital learning, visit the Spotlight blog at spotlight.macfound.org. About the MacArthur Foundation The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private, independent grantmaking institution dedicated to helping groups and individuals foster lasting improvement in the human condition.With assets of $5.5 billion, the Foundation makes grants totaling approximately $200 million annually. For more information or to sign up for MacArthur’s monthly electronic newsletter, visit www.macfound.org. The MacArthur Foundation 140 South Dearborn Street, Suite 1200 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Tel.(312) 726-8000 www.digitallearning.macfound.org An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. -

MEDIA CONSUMPTION HABITS DURING the LOCKDOWN Impact Assessment of Media Usage During Quarantine - April 2020

MEDIA CONSUMPTION HABITS DURING THE LOCKDOWN Impact Assessment of Media Usage During Quarantine - April 2020 ©2020 IpsosKE_AUM_ Media Consumption Habits I April 2020 SNAPSHOT SUMMARY This report snapshot highlights the situational analysis on media access and consumption habits at a time when a significant proportion of the continent population is either in lockdown and for some, working from home due to the Covid-19 crisis. From our analysis, here are some interesting observations: Increased media time; high consumption of TV programing Increased levels of anxiety and Online activities Increased household Increased spend on food and expenditure; school going healthcare hence less saving. children are at home CRISIS • Media is awash with stories of job loses meaning budgetary Increased idle time for constraints at the family level family bonding • Reduced consumer purchase power With heavy media consumption by a hungry audience, therein SO WHAT? lies the opportunity for creative content development. ©2020 IpsosKE_AUM_ Media Consumption Habits I April 2020 METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLING Survey Demographic Profile Rift Valley 1 25% National survey achieved a total sample of Eastern 2 15% 2,049 respondents 1 Central 3 13% 2 8 Nyanza 4 13% The representative sample covered the 18+ 37% 6 URBAN 63% Nairobi 5 11% population across all regions of Kenya 4 3 RURAL Western 6 10% 5 Coast 7 9% The survey was conducted telephonically 7 N. Eastern 8 4% (CATI) from 9th to 19th April 2020 49% 51% MALE FEMALE AGE SOCIAL ECONOMIC CLASS Refused 2% 45yrs + 23% LSM -

The Effect of Media Literacy Training on the Self-Esteem and Body-Satisfaction

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2016 The ffecE t of Media Literacy Training on the Self- Esteem and Body-Satisfaction Among Fifth Grade Girls Holly Mathews Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Psychiatric and Mental Health Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Holly Mathews has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Hedy Dexter, Committee Chairperson, Psychology Faculty Dr. Brandon Cosley, Committee Member, Psychology Faculty Dr. Neal McBride, University Reviewer, Psychology Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2016 Abstract The Effect of Media Literacy Training on the Self-Esteem and Body-Satisfaction Among Fifth Grade Girls by Holly Mathews MS, Walden University, 2010 BS, The Pennsylvania State University, 2000 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Clinical Psychology Walden University December 2016 Abstract Repeated exposure to media images that portray women as sex objects can have negative long-term effects on self-esteem beginning in preadolescence. -

Bolivia: Presidential Resignation and Aftermath

INSIGHTi Bolivia: Presidential Resignation and Aftermath Clare Ribando Seelke Specialist in Latin American Affairs Updated November 14, 2019 On November 10, 2019, Bolivian President Evo Morales of the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party resigned and subsequently received asylum in Mexico. Bolivia’s military had recommended that Morales step down to prevent an escalation of violence after weeks of protests alleging fraud in the October 20, 2019, presidential election. While Morales has described his ouster as a “coup,” the opposition has described it as a “popular uprising” against an authoritarian leader. The three individuals in line to succeed Morales (the vice president and the presidents of the senate and the chamber of deputies) also resigned. Opposition Senator Jeanine Añez, formerly second vice president of the senate, declared herself senate president and then assumed the position of interim president on November 12, 2019; MAS legislators do not recognize her authority. The U.S. Department of State supported the findings of an Organization of American States (OAS) audit that found enough irregularities in the October elections to recommend a new election. President Trump praised Morales’s resignation. State Department officials have called for all parties to refrain from violence and issued a travel warning for Bolivia. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo applauded Añez for stepping up as interim president. Congressional concern about Bolivia has increased. S.Res. 35, approved in April 2019, expresses concern over Morales’s efforts to circumvent term limits in Bolivia. Morales Government (2006-2019) Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous leader, had governed since 2006 as head of the MAS party. -

Measuring the News and Its Impact on Democracy COLLOQUIUM PAPER Duncan J

Measuring the news and its impact on democracy COLLOQUIUM PAPER Duncan J. Wattsa,b,c,1, David M. Rothschildd, and Markus Mobiuse aDepartment of Computer and Information Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; bThe Annenberg School of Communication, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; cOperations, Information, and Decisions Department, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; dMicrosoft Research, New York, NY 10012; and eMicrosoft Research, Cambridge, MA 02142 Edited by Dietram A. Scheufele, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Susan T. Fiske February 21, 2021 (received for review November 8, 2019) Since the 2016 US presidential election, the deliberate spread of pro-Clinton articles.” In turn, they estimated that “if one fake misinformation online, and on social media in particular, has news article were about as persuasive as one TV campaign ad, generated extraordinary concern, in large part because of its the fake news in our database would have changed vote shares by potential effects on public opinion, political polarization, and an amount on the order of hundredths of a percentage point,” ultimately democratic decision making. Recently, however, a roughly two orders of magnitude less than needed to influence handful of papers have argued that both the prevalence and the election outcome. Subsequent studies have found similarly consumption of “fake news” per se is extremely low compared with other types of news and news-relevant content. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

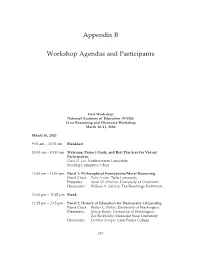

Appendix B Workshop Agendas and Participants

Appendix B Workshop Agendas and Participants First Workshop National Academy of Education (NAEd) Civic Reasoning and Discourse Workshop March 10–11, 2020 March 10, 2020 9:00 am – 10:00 am Breakfast 10:00 am – 10:30 am Welcome, Project Goals, and Best Practices for Virtual Participation Carol D. Lee, Northwestern University Steering Committee Chair 10:30 am – 12:00 pm Panel 1: Philosophical Foundations/Moral Reasoning Panel Chair: Peter Levine, Tufts University Presenter: Sarah M. Stitzlein, University of Cincinnati Discussant: William A. Galston, The Brookings Institution 12:00 pm – 12:45 pm Break 12:45 pm – 2:15 pm Panel 2: History of Education for Democratic Citizenship Panel Chair: Walter C. Parker, University of Washington Presenters: Nancy Beadie, University of Washington Zoë Burkholder, Montclair State University Discussant: Cristina Groeger, Lake Forest College 437 438 EDUCATING FOR CIVIC REASONING AND DISCOURSE 2:30 pm – 4:00 pm Panel 3: Learning Environments and School/Classroom Climate Panel Chair: Judith Torney-Purta, University of Maryland Presenters: Carolyn Barber, University of Missouri-Kansas City Christopher H. Clark, University of North Dakota Discussant: David Campbell, University of Notre Dame 4:15 pm – 5:45 pm Panel 4: Digital Literacy and the Health of Democratic Practice Panel Chair: Joseph Kahne, University of California, Riverside Presenters: Antero Godina Garcia, Stanford University Nicole Mirra, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Discussant: Donna Phillips, District of Columbia Public Schools 5:45 pm Meeting Adjourns for the Day March 11, 2020 9:00 am – 10:00 am Breakfast 10:00 am – 11:30 am Panel 5: Disciplinary Underpinnings and Psychological Foundation Panel Chairs: Carol D. -

THOMAS, OLIVER MELTON-CHRISTIAN, Ph.D. Toward a Pedagogy of Critical Liberative Theological Consciousness: Cultivating Students As Agents of Social Change

THOMAS, OLIVER MELTON-CHRISTIAN, Ph.D. Toward a Pedagogy of Critical Liberative Theological Consciousness: Cultivating Students as Agents of Social Change. (2020) Directed by Dr. Leila Villaverde. 233 pp. The central task of Toward a Pedagogy of Critical Liberative Theological Consciousness: Cultivating Students as Agents of Social Change is discovering pedagogical and theological wisdom for social transformation, through a dialogue with James H. Cone and Paulo Freire. Accordingly, it uncovers a deep concern with liberation, as a theological thrust countering oppressive ideologies, through curiosity, awareness, reflection, and response. I uncover this concern for liberation from dominant, oppressive ideologies by analyzing God of the Oppressed by James H. Cone and Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire. I do so by utilizing critical hermeneutics, historical criticism, and critical exegesis. By way of their seminal works, God of the Oppressed and Pedagogy of the Oppressed, I engage these theorists in an imaginative dialogue so as to lay a foundation Toward a Pedagogy of Critical Liberative Theological Consciousness. As I perceive it, liberation may manifest within various aspects of pedagogical and theological activity – among them are rereading history, critical inquiry, lived experience, resistance to oppression, and scriptural interpretation. Therefore, cultivating a critical liberative theological consciousness is a process of disentangling theological and social formations that are destructive, constructing new/different ways of -

Abolitionist Computer Science Teaching: Moving from Access to Justice

Abolitionist Computer Science Teaching: Moving from Access to Justice Allison Ivey Stephany RunningHawk Johnson Max Skorodinsky Jimmy Snyder Department of Education Studies Member of Oglala Lakota Nation Department of Education Studies Kickapoo Tribe of Kansas University of Oregon Department of Teaching and University of Oregon Department of Education Studies Eugene, USA Learning Eugene, USA University of Oregon [email protected] Washington State University [email protected] Eugene, USA Pullman, USA [email protected] [email protected] Joanna Goode Department of Education Studies University of Oregon Eugene, USA [email protected] Abstract —As high school computer science course offerings what takes place in the classroom beyond the initial level of have expanded over the past decade, gaps in race and gender have access. While this concern has been continually raised by remained. This study embraces the “All” in the “CS for All” scholars, [5, 6] much of the conversation, centered around the movement by shifting beyond access and toward abolitionist “CS for All” movement [7, 8] has been focused on notions of computer science teaching. Using data from professional equity in terms of access to, and participation in, existing development observations and interviews, we lift the voices of classes [9, 10], without taking into account the pedagogical BIPOC CS teachers and bring together tenets put forth by Love commitments being centered. (2019) for abolitionist teaching along with how these tenets map onto the work occurring in CS classrooms. Our findings indicate Given the current sociopolitical context, the importance of BIPOC teacher representation in CS classrooms reconceptualizing the field of CS to intentionally consider and ways abolitionist teaching tenets can inform educator’s efforts equity through understanding and dismantling racism is vital at moving beyond broadening participation and toward radical if we are to remedy the historical and persisting gaps in inclusion, educational freedom, and self-determination, for ALL. -

IHRC Submission on Bolivia

VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHT TO LIFE, RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, RIGHT TO ASSEMBLY & ASSOCIATION, AND OTHERS: ONGOING HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BOLIVIA Submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions from Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic Cc: Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers Special Rapporteur on the f reedom of opinion and expression Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism The International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) at Harvard Law School seeks to protect and promote human rights and internation-al humanitarian law through documentation; legal, factual, and stra-tegic analysis; litigation before national, regional, and internation-al bodies; treaty negotiations; and policy and advocacy initiatives. Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations to the U.N. Special Rapporteurs ........................................................................... 2 Facts ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Background on the Current Crisis ........................................................................................................ 3 State Violence Against Protesters -

Toward Abolitionist Transliteracies Ecologies and an Anti-Racist Translingual Pedagogy

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 6-2021 Beyond Authorization: Toward Abolitionist Transliteracies Ecologies and an Anti-Racist Translingual Pedagogy Lindsey Albracht The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4285 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BEYOND AUTHORIZATION: TOWARD ABOLITIONIST TRANSLITERACIES ECOLOGIES AND AN ANTI-RACIST TRANSLINGUAL PEDAGOGY by LINDSEY ALBRACHT A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 ©2021 LINDSEY ALBRACHT All Rights Reserved ii Beyond Authorization: Toward Abolitionist Transliteracies Ecologies and an Anti-Racist Translingual Pedagogy by Lindsey Albracht This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________ ______________________________________ Date Amy J. Wan Chair of Examining Committee _________________ _____________________________________ Date: Kandice Chuh Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Mark McBeth Jessica Yood THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Beyond Authorization: Toward Abolitionist Transliteracies Ecologies and an Anti-Racist Translingual Pedagogy by Lindsey Albracht Advisor: Amy J. Wan This project explores the recent paradigm shift within Writing Studies toward a translingual approach, situating many of the critiques of this approach as limitations produced by dominant liberal models of Writing Studies pedagogy. -

The Dreamwork of Transformation in Teacher Education

INTRODUCTION The Dreamwork of Transformation in Teacher Education KARYN SANDLOS University of Illinois at Chicago BRIAN CASEMORE George Washington University H. JAMES GARRETT University of Georgia HIS SPECIAL ISSUE ENGAGES THE LIMITS of the stories we tell ourselves in teacher T education through the idea/image/metaphor/vantage of dreams and dreaming. Ever since the publication of Freud’s (1900) Interpretation of Dreams, the status of dreams and dreaming has persisted in inquiry as a means to resist—through practices of analysis, interpretation, and social critique—our most taken for granted understandings of ourselves and others. Freud (1914/2001) argued that dreams act as “the guardian of sleep” (p. 38), allowing us to become conversant with parts of ourselves that are difficult to know or accept. Pinar’s (2004) reference to the contemporary landscape of educational reform as “the nightmare that is the present” inaugurates his book, What is Curriculum Theory? (p. 5). Ta-Nehisi Coates’ (2015) elaboration of “The Dream,” in Between the World and Me, identifies national mythologies of race as structuring the persistence of white supremacy. Following in this tradition of scholarship on dreams, the writers in this special issue demonstrate that dreamwork—as understood through psychoanalysis, social theory, and curriculum studies—complicates the subjective and social dimensions of teacher education, expanding the sphere of teaching and our sense of the teacher as subject. In this issue, we ask: What can we make of the various versions of dreaming if we use them to think anew about our work in the spaces of teacher education? A linear theory of learning predominates the structures and features of most teacher education programs.