Joe Orton's 'Until She Screams,' Oh! Calcutta! and the Permisive 1960S Saunders, Graham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audience Enrichment Guide

KEY ART: EXTENDED BACKGROUND Girl From the North Country | Study Guide Part One 1 Is created by cropping the layered extended background file. FILE NAME: GFTNC_EXT_COLORADJUST_ LAYERS_8.7.19_V3 ARTS EDUCATION AND ACTIVATION CREATED IN COLLABORATION WITH TDF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT 4 Girl From the North Country | Study Guide Part One 2 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This guide is intentionally designed to be a flexible teaching tool for teachers and facilitators focusing on different aspects of Girl From The North Country, with the option to further explore and activate knowledge. The guide is broken up into three sections: I. Getting to know the show, Conor McPherson story II. The Great Depression and historical context III. Bob Dylan and his music Activations are meant to take students from the realm of knowing a thing or fact into the realm of thinking and feeling. Activations can be very sophisticated, or simple, depending on the depth of exploration teachers and facilitators want to do with their students, or the age group they are working with. Girl From the North Country | Study Guide Part One 3 CONOR MCPHERSON ON BEING INSPIRED BY BOB DYLAN’S MUSIC ELYSA GARDNER for Broadwaydirect.com OCTOBER 1, 2019 For the celebrated Irish playwright Conor songs up; by setting it in the ‘30s, we could McPherson, Girl From the North Country rep- do them another way. I knew I wanted a lot of resents a number of firsts: his first musical, his vocals and a lot of choral harmonies.” first work set in the United States, and, oh yes, A guitarist himself, McPherson had always his first project commissioned by Bob Dylan been interested in Dylan’s music, but he — the first theater piece ever commissioned admits, “I was not one of those people who by the iconic Nobel Prize–winning singer/ could cover every decade of his career. -

The Byrds' Mcguinn at Joe College by Kent Hoover Rock in That Era

OUTSIDE WEATHER Temperatures in the 70s Baseball team loses to for Joe College Weekend, The Chronicle li ttle chance of rain today. Duke University Volume 72, Number 135 Friday, April 15,1977 Durham, North Carolina Search reopened for Trinity dean By George Strong to his discipline," Turner observed. The University is again searching for a "There is a real sense in which a staff replacement for David Clayborne, the as position is a detour for someone who is sistant dean of Trinity College who re getting started." signed last summer. In late March, Wright informed John George Wright, the history graduate Fein, dean of Trinity College, of Ken student hired several months ago to be an tucky's offer. "I felt obliged — though assistant dean beginning this fall, has ac regretful — to release him from his ob cepted a faculty position at the University ligation to Duke," Fein said. of Kentucky, his alma mater. "I don't know whether I expected this or His decision leaves Trinity College once not," commented Richard Wells, associate again without a black academic dean. dean of Trinity College. 1 thought maybe Wright maintained that neither qualms it would work out But good people are about the Duke administration nor finan always in demand" cial considerations had entered his de Wells is heading up the screening com cision. mittee for applicants to the vacated posi Couldn't refuse tion. Fein and Gerald Wison, coordinator 1 knew I would eventually move into for the dean's staff, join Wells on the com "What kind of kids eat Armour hot dogs?" Harris Asbeil, Joe College chef, my academic field," he said, "and once the mittee. -

Joe Orton: the Oscar Wilde of the Welfare State

JOE ORTON: THE OSCAR WILDE OF THE WELFARE STATE by KAREN JANICE LEVINSON B.A. (Honours), University College, London, 1972 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of English) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1977 (c) Karen Janice Levinson, 1977 ii In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of English The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 30 April 1977 ABSTRACT This thesis has a dual purpose: firstly, to create an awareness and appreciation of Joe Orton's plays; moreover to establish Orton as a focal point in modern English drama, as a playwright whose work greatly influenced and aided in the definition of a form of drama which came to be known as Black Comedy. Orton's flamboyant life, and the equally startling method of his death, distracted critical attention from his plays for a long time. In the last few years there has been a revival of interest in Orton; but most critics have only noted his linguistic ingenuity, his accurate ear for the humour inherent in the language of everyday life which led Ronald Bryden to dub him "the Oscar Wilde of Welfare State gentility." This thesis demonstrates Orton's treatment of social matters: he is concerned with the plight of the individual in society; he satirises various elements of modern life, particularly those institutions which wield authority (like the Church and the Police), and thus control men. -

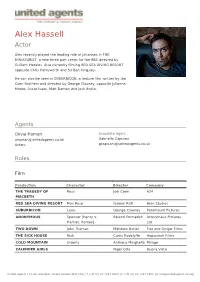

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

Still on the Road 1990 Us Fall Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 1990 US FALL TOUR OCTOBER 11 Brookville, New York Tilles Center, C.W. Post College 12 Springfield, Massachusetts Paramount Performing Arts Center 13 West Point, New York Eisenhower Hall Theater 15 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 16 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 17 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 18 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 19 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 21 Richmond, Virginia Richmond Mosque 22 Pittsburg, Pennsylvania Syria Mosque 23 Charleston, West Virginia Municipal Auditorium 25 Oxford, Mississippi Ted Smith Coliseum, University of Mississippi 26 Tuscaloosa, Alabama Coleman Coliseum 27 Nashville, Tennessee Memorial Hall, Vanderbilt University 28 Athens, Georgia Coliseum, University of Georgia 30 Boone, North Carolina Appalachian State College, Varsity Gymnasium 31 Charlotte, North Carolina Ovens Auditorium NOVEMBER 2 Lexington, Kentucky Memorial Coliseum 3 Carbondale, Illinois SIU Arena 4 St. Louis, Missouri Fox Theater 6 DeKalb, Illinois Chick Evans Fieldhouse, University of Northern Illinois 8 Iowa City, Iowa Carver-Hawkeye Auditorium 9 Chicago, Illinois Fox Theater 10 Milwaukee, Wisconsin Riverside Theater 12 East Lansing, Michigan Wharton Center, University of Michigan 13 Dayton, Ohio University of Dayton Arena 14 Normal, Illinois Brayden Auditorium 16 Columbus, Ohio Palace Theater 17 Cleveland, Ohio Music Hall 18 Detroit, Michigan The Fox Theater Bob Dylan 1990: US Fall Tour 11530 Rose And Gilbert Tilles Performing Arts Center C.W. Post College, Long Island University Brookville, New York 11 October 1990 1. Marines' Hymn (Jacques Offenbach) 2. Masters Of War 3. Tomorrow Is A Long Time 4. -

South Coast Repertory Is a Professional Resident Theatre Founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson

IN BRIEF FOUNDING South Coast Repertory is a professional resident theatre founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson. VISION Creating the finest theatre in America. LEADERSHIP SCR is led by Artistic Director David Ivers and Managing Director Paula Tomei. Its 33-member Board of Trustees is made up of community leaders from business, civic and arts backgrounds. In addition, hundreds of volunteers assist the theatre in reaching its goals, and about 2,000 individuals and businesses contribute each year to SCR’s annual and endowment funds. MISSION South Coast Repertory was founded in the belief that theatre is an art form with a unique power to illuminate the human experience. We commit ourselves to exploring urgent human and social issues of our time, and to merging literature, design, and performance in ways that test the bounds of theatre’s artistic possibilities. We undertake to advance the art of theatre in the service of our community, and aim to extend that service through educational, intercultural, and community engagement programs that harmonize with our artistic mission. FACILITY/ The David Emmes/Martin Benson Theatre Center is a three-theatre complex. Prior to the pandemic, there were six SEASON annual productions on the 507-seat Segerstrom Stage, four on the 336-seat Julianne Argyros Stage, with numerous workshops and theatre conservatory performances held in the 94-seat Nicholas Studio. In addition, the three-play family series, “Theatre for Young Audiences,” produced on the Julianne Argyros Stage. The 20-21 season includes two virtual offerings and a new outdoors initiative, OUTSIDE SCR, which will feature two productions in rotating rep at the Mission San Juan Capistrano in July 2021. -

Australian Academy Announces Feature Length Documentary Nominees for 4Th AACTA Awards

MEDIA RELEASE Strictly embargoed until Wednesday 10th September, 2014 Australian Academy Announces Feature Length Documentary Nominees for 4th AACTA Awards The Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) today announced feature length documentary nominees for the 4th AACTA Awards, marking Australia’s finest documentaries of the last year. In an exceptional year for Australian documentary, this year’s nominees have captured audiences and critics at home and abroad with gripping storytelling, subjects and subject matter. ‘The Outsiders’ feature alongside the ‘glitterati,’ with sex, drugs, rock n’ roll, jailed subjects, jailed filmmakers, murder and a feminist uprising confidently competing alongside scenes from the deepest reach of the sea. NOMINEES FOR BEST FEATURE LENGTH DOCUMENTARY All This Mayhem. George Pank, Eddie Martin, James Gay-Rees DEEPSEA CHALLENGE 3D. Andrew Wight, Brett Popplewell The Last Impresario. Nicole O'Donohue Ukraine Is Not A Brothel. Kitty Green, Jonathan auf der Heide, Michael Latham The Best Feature Length Documentary nominees will screen along with all Feature Films In Competition and all Short Film nominees at the AACTA Awards Screenings in Sydney and Melbourne during October, and online via AACTA TV. Screenings and AACTA TV are accessible to members of AACTA (accredited screen professionals) and AFI members (members of the public). The Best Feature Length Documentary winner will be announced at the 4th AACTA Awards, Australia’s preeminent film and television Awards, in Sydney, home of the AACTA Awards, in January 2015. ABOUT THE BEST FEATURE LENGTH DOCUMENTARY NOMINEES All This Mayhem captures the fractured lives of two former champion pro skaters, brothers Tas and Ben Pappas, whose technical skill took the skating world by storm, but whose personal lives tragically spiralled into a dangerous world of drugs, jail, murder, depression and death. -

And Dylan's Romanticism

“Isis” and Dylan’s Romanticism --John Hinchey I want to talk mainly about “Isis,” a song Dylan co-wrote with Off Broadway director Jacques Levy.1 “Isis” was the first of several songs that Dylan wrote with Levy during the summer of 1975, and this fruitful col- laboration yielded seven of the nine songs released at the end of that year on Desire. I’ve chosen “Isis” mainly because it’s an interesting and entertaining song in its own right, but also because it offers a useful vantage point for considering Dylan’s Romanticism, an abiding element in his artistic tem- perament that doesn’t get nearly as much attention as you’d think it would. Adventure, mystery, discovery, renewal, the vista of inexhaustible pos- sibility--these are the hallmarks of Romance. Its essence is an aspiration for a world without bounds, a vision of a life of unlimited possibility. “Forever Young” is a quintessentially Romantic idea, as is the popular conception of Heaven. Romanticism, you could say, is the impulse to find Heaven on Earth. It can sound ridiculous when you state it flat out this way, but al- 1 This is a slightly revised version of a paper presented at “A Series of Interpretations of Bob Dylan's Lyrical Works,” a conference hosted by the Dartmouth College English Department, August 11-13, 2006. Quotations of Dylan's lyrics are from the original official recordings, unless otherwise noted. When quoting lines extensively, I revert to the principle I used in Like a Complete Unknown (Ann Arbor: Stealing Home Press, 2002): “I’ve had to determine the ‘spaces between words’ for myself. -

If a Thing's Worth Doing, It's Worth Doing on Public Television–Joe Orton's

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Charlton, James Martin ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9066-4705 (2014) If a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth doing on public television – Joe Orton’s plays on television. In: Theatre and Television: Adaptation, Production, Performance, 19-20 Feb 2015, Alexandra Palace. [Conference or Workshop Item] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/18929/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. -

N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd”

Platform , Vol. 3, No. 1 N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd” Neema Parvini (Royal Holloway, University of London) In 1958, in the Observer , Kenneth Tynan wrote of “a dazzling new playwright,” with his inimitable enthusiasm he declared: “I am ready to burn my boats and promise [that] N.F. Simpson [is] the most gifted comic writer the English stage has discovered since the war” (Tynan 210). Now, in 2008, despite a recent West End revival, 1 few critics would cite Simpson at all and debates regarding the “most gifted comic writer” of the English stage would invariably be centred on Tom Stoppard, Joe Orton, Samuel Beckett or, for those with a more morose sense of humour, Harold Pinter. Part of the reason for Simpson’s critical decline can be put down to protracted periods of silence; after his run of critically and commercially successful plays with The English Stage Company, 2 Simpson only produced two further full length plays: The Cresta Run (1965) and Was He Anyone? (1972). Of these, the former was poorly received and the latter only reached the fringe theatre. 3 As Stephen Pile recently put it, “in 1983, Simpson himself vanished” with no apparent fixed address. The other reason that may be cited is that, more than any other British writer of his time, Simpson was associated with “The Theatre of the Absurd.” As the vogue for the style died out in London, Simpson’s brand of Absurdism simply went out of fashion. John Russell Taylor offers perhaps the most scathing version of that argument: “whether one likes or dislikes N.F. -

Still on the Road Early 1976 Sessions

STILL ON THE ROAD EARLY 1976 SESSIONS JANUARY 22 Los Angeles, California Instrumental Rentals Studio, Rehearsals 23 Los Angeles, California Instrumental Rentals Studio, Rehearsals 23 Los Angeles, California The Troubadour 25 Houston, Texas Houston Astro drome, Night Of The Hurricane 2 27 Austin, Texas Municipal Auditorium MARCH 30 Malibu, California Shangri -La Studios Malibu, California Shangri -La Studios Still On The Road: 1976 Early sessions 3240 Instrumental Rentals Studio Los Angeles, California 22 January 1976 Rehearsals for the second Hurricane Carter Benefit concert. 1. You Ain't Goin' Nowhere 2. One More Cup Of Coffee (Valley Below) 3. Oh, Sister (Bob Dylan –Jacques Levy/Bob Dylan) 4. Sara 5. Mozambique (Bob Dylan –Jacques Levy/Bob Dylan) Bob Dylan (guitar & vocal), Bob Neuwirth (guitar), Scarlet Rivera (violin), T-bone J. Henry Burnett (guitar), Roger McGuinn (guitar), Mick Ronson (guitar), Rob Stoner (bass), Steven Soles (guitar), David Mansfield (steel guitar, mandolin, violin, dobro), Howie Wyeth (drums). Note. 1 is only a fragment. Bootlegs Days before the Hurricane (Come One! Come All!) . No Label 93-BD-023. Going Going Guam . White Bear / wb05/06/07/08. Reference. Les Kokay: Songs of the Underground. Rolling Thunder Revue . Private publication 2000, page 67. Stereo studio recording, 20 minutes. Still On The Road: 1976 Early sessions 3245 Instrumental Rentals Studio Los Angeles, California 23 January 1976 Rehearsals for the second Hurricane Carter Benefit concert. 1. Just Like A Woman 2. Just Like A Woman 3. Just Like A Woman 4. Just Like A Woman 5. Just Like A Woman 6. Just Like A Woman 7. Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever (Don Hunter/Stevie Wonder) 8.