Nostalgia, Retroscapes, and the Dungeon Crawl Classics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lewis Carroll: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND by Lewis Carroll with fourty-two illustrations by John Tenniel This book is in public domain. No rigths reserved. Free for copy and distribution. This PDF book is designed and published by PDFREEBOOKS.ORG Contents Poem. All in the golden afternoon ...................................... 3 I Down the Rabbit-Hole .......................................... 4 II The Pool of Tears ............................................... 9 III A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale .................................. 14 IV The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill ................................. 19 V Advice from a Caterpillar ........................................ 25 VI Pig and Pepper ................................................. 32 VII A Mad Tea-Party ............................................... 39 VIII The Queen’s Croquet-Ground .................................... 46 IX The Mock Turtle’s Story ......................................... 53 X The Lobster Quadrille ........................................... 59 XI Who Stole the Tarts? ............................................ 65 XII Alice’s Evidence ................................................ 70 1 Poem All in the golden afternoon Of wonders wild and new, Full leisurely we glide; In friendly chat with bird or beast – For both our oars, with little skill, And half believe it true. By little arms are plied, And ever, as the story drained While little hands make vain pretence The wells of fancy dry, Our wanderings to guide. And faintly strove that weary one Ah, cruel Three! In such an hour, To put the subject by, Beneath such dreamy weather, “The rest next time –” “It is next time!” To beg a tale of breath too weak The happy voices cry. To stir the tiniest feather! Thus grew the tale of Wonderland: Yet what can one poor voice avail Thus slowly, one by one, Against three tongues together? Its quaint events were hammered out – Imperious Prima flashes forth And now the tale is done, Her edict ‘to begin it’ – And home we steer, a merry crew, In gentler tone Secunda hopes Beneath the setting sun. -

MAY 19Th 2018

5z May 19th We love you, Archivist! MAY 19th 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Dragon Magazine #151

Issue #151 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Vol. XIV, No. 6 Into the Eastern Realms: November 1989 11 Adventure is adventure, no matter which side of the ocean you’re on. Publisher The Ecology of the Kappa David R. Knowles Jim Ward 14 Kappa are strange, but youd be wise not to laugh at them. Editor Soldiers of the Law Dan Salas Roger E. Moore 18 The next ninja you meet might actually work for the police. Fiction editor Earn Those Heirlooms! Jay Ouzts Barbara G. Young 22Only your best behavior will win your family’s prize katana. Assistant editors The Dragons Bestiary Sylvia Li Anne Brown Dale Donovan 28The wang-liang are dying out — and they’d like to take a few humans with them. Art director Paul Hanchette The Ecology of the Yuan-ti David Wellman 32To call them the degenerate Spawn of a mad god may be the only nice Production staff thing to say. Kathleen C. MacDonald Gaye OKeefe Angelika Lukotz OTHER FEATURES Subscriptions The Beastie Knows Best Janet L. Winters — Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser 36 What are the best computer games of 1989? You’ll find them all here. U.S. advertising Role-playing Reviews Sheila Gailloreto Tammy Volp Jim Bambra 38Did you ever think that undead might be . helpful? U.K. correspondent The Role of Books John C. Bunnell and U.K. advertising 46 New twists on an old tale, and other unusual fantasies. Sue Lilley The Role of Computers — Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser 52 Fly a Thunderchief in Vietnam — or a Silpheed in outer space. -

Fantasy Adventure Game Expert Rulebook

TABLE OF CONTENTS Reference Charts from D&D® Basic X2 Character Attacks X26 PART 1: INTRODUCTION X3 Monster Attacks X26 How to Use This Book X3 PART 6: MONSTERS X27 The Scope of the Rules X3 MONSTER LIST: Animals to Wyvern . X28 Standard Terms Used in This Book X3 PART 7: TREASURE X43 Assisting A Novice Player X3 Treasure Types X43 The Wilderness Campaign X3 Magic Items X44 High and Low Level Characters X4 Explanations X45 Using D&D® Expert Rules With an Early Swords X45 Edition of the D&D® Basic Rules X4 Weapons and Armor X48 PART 2: PLAYER CHARACTER INFORMATION X5 Potions X48 Charts and Tables X5 Scrolls X48 Character Classes X7 Rings X49 CLERICS X7 Wands, Staves and Rods X49 DWARVES X7 Miscellaneous Magic Items X50 ELVES X7 PART 8: DUNGEON MASTER INFORMATION X51 FIGHTERS X7 Handling Player Characters X51 HALFLINGS X7 Magical Research and Production X51 MAGIC-USERS X7 Castles, Strongholds and Hideouts X52 THIEVES X8 Designing a Dungeon (recap) X52 Levels Beyond Those Listed X8 Creating an NPC Party X52 Cost of Weapons and Equipment X9 NPC Magic Items X52 Explanation of Equipment X9 Designing a Wilderness X54 PART 3: SPELLS Xll Wandering Monsters X55 CLERICAL SPELLS Xll Travelling In the Wilderness X56 First Level Clerical Spells Xll Becoming Lost X56 Second Level Clerical Spells X12 Wilderness Encounters X57 Third Level Clerical Spells X12 Wilderness Encounter Tables X57 Fourth Level Clerical Spells X13 Castle Encounters X59 Fifth Level Clerical Spells X13 Dungeon Mastering as a Fine Art X59 MAGIC-USER AND ELF SPELLS X14 Sample Wilderness Key and Maps X60 First Level Magic-User and Elf Spells SampleX14 fileHuman Lands X60 Second Level Magic-User and Elf Spells X14 Non-Humans '. -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

CR174 GOODMAN.Qxd

GAMES IN FOCUS Dungeon Crawl Classics Use DCC World to build a module business by our years after the release of Dungeon gorgeously illustrated poster-sized world maps which notate the locations of every Dungeon Joseph Crawl Classics #1: Idylls of the Rat F King, the Dungeon Crawl Classics line Crawl Classics module in the series. The Goodman remains one of the industry’s best-recognized boxed set includes three defined adventure President, brands of d20 System adventure modules. paths that show a Dungeon Master how to Goodman With the imminent publication of #35 in the link these adventures together. Of course, all Games series — a milestone for any role-playing of the modules must be purchased separately. game line, especially a d20 line past the boom So the Dungeon Master who buys the boxed — publisher Goodman Games announced set will be back in your store two weeks later, plans to make the 35th DCC a deluxe boxed purchasing the other Dungeon Crawl Clas- set. This $69.99 MSRP product is a complete sics modules he needs to set up his cam- campaign setting that also presents a unique paign! From a opportunity for retailers — not only will it This placement within a larger line is a very make for a profitable sale on a single product, important trait to consider. Selling a role-play- retailer’s it can also be used to sell an entire line of ing game product with an MSRP higher than perspective, products. $40 is always difficult, and it becomes more DCC #35 Dungeon Crawl Classics #35: Gazetteer difficult the higher the price goes. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Dragon Magazine

May 1980 The Dragon feature a module, a special inclusion, or some other out-of-the- ordinary ingredient. It’s still a bargain when you stop to think that a regular commercial module, purchased separately, would cost even more than that—and for your three bucks, you’re getting a whole lot of magazine besides. It should be pointed out that subscribers can still get a year’s worth of TD for only $2 per issue. Hint, hint . And now, on to the good news. This month’s kaleidoscopic cover comes to us from the talented Darlene Pekul, and serves as your p, up and away in May! That’s the catch-phrase for first look at Jasmine, Darlene’s fantasy adventure strip, which issue #37 of The Dragon. In addition to going up in makes its debut in this issue. The story she’s unfolding promises to quality and content with still more new features this be a good one; stay tuned. month, TD has gone up in another way: the price. As observant subscribers, or those of you who bought Holding down the middle of the magazine is The Pit of The this issue in a store, will have already noticed, we’re now asking $3 Oracle, an AD&D game module created by Stephen Sullivan. It for TD. From now on, the magazine will cost that much whenever we was the second-place winner in the first International Dungeon Design Competition, and after looking it over and playing through it, we think you’ll understand why it placed so high. -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

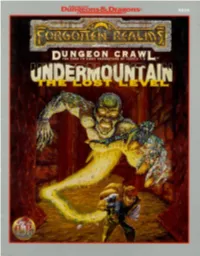

Undermountain: the Lost Level by Steven E

Undermountain: The Lost Level by Steven E. Schend Table of Contents Credits Introduction . 2 Design: Steven E. Schend Hidden Stories . 2 Editing: Bill Olmesdahl Ways In and Out . 3 Cover Art: Alan Pollack Interior Art: Earl Geier Rumors Of Undermountain . 4 Cartography: Dennis Kauth Notes On The Lost Level . .4 Typography: Tracey L. Isler The Lost Level . .6-28 Art Coordination: Robert J. Galica Entry Portal: Room #1 . .6 Melairest: Rooms #2-#17 . .6-19 A DVANCE DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, AD&D, FORGOTTEN Sargauth Falls: Room #18 . 19 REALMS and DUNGEON MASTER are registered trademarks The Prison: Rooms #19#24 . .20-22 owned by TSR, Inc. DUNGEON CRAWL, MONSTROUS MANUAL, The Hunters Lair: Rooms #25--#28 . .22-26 and the TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Egress Perilous: Rooms #29 & #30 . 26-28 Lost NPCs and Magic . .29-32 Random House and its affiliate companies have worldwide dis- tribution rights in the book trade for English-language products of TSR, Inc. Distributed to the book and hobby trade in the United Kingdom by TSR Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. ©1996 TSR, Inc. All rights reserved. Made in the U.S.A. TSR, Inc. TSR Ltd. 201 Sheridan Springs Rd. 120 Church End Lake Geneva Cherry Hinton WI 53147 Cambridge CB1 3LB U.S.A. United Kingdom ISBN 0-7869-0399-6 9519 Introduction elcome to the first official DUNGEON CRAWLS™ adventure module, where we return to the timeless depths of the Realms’ oldest and greatest dungeon: Un- dermountain! DUNGEON CRAWL adventures are created as stand-alone quests, but can easily be adapted to existing campaigns. -

Folha De Rosto ICS.Cdr

“For when established identities become outworn or unfinished ones threaten to remain incomplete, special crises compel men to wage holy wars, by the cruellest means, against those who seem to question or threaten their unsafe ideological bases.” Erik Erikson (1956), “The Problem of Ego Identity”, p. 114 “In games it’s very difficult to portray complex human relationships. Likewise, in movies you often flit between action in various scenes. That’s very difficult to do in games, as you generally play a single character: if you switch, it breaks immersion. The fact that most games are first-person shooters today makes that clear. Stories in which the player doesn’t inhabit the main character are difficult for games to handle.” Hideo Kojima Simon Parkin (2014), “Hideo Kojima: ‘Metal Gear questions US dominance of the world”, The Guardian iii AGRADECIMENTOS Por começar quero desde já agradecer o constante e imprescindível apoio, compreensão, atenção e orientação dos Professores Jean Rabot e Clara Simães, sem os quais este trabalho não teria a fruição completa e correta. Um enorme obrigado pelos meses de trabalho, reuniões, telefonemas, emails, conversas e oportunidades. Quero agradecer o apoio de família e amigos, em especial, Tia Bela, João, Teté, Ângela, Verxka, Elma, Silvana, Noëmie, Kalashnikov, Madrinha, Gaivota, Chacal, Rita, Lina, Tri, Bia, Quelinha, Fi, TS, Cinco de Sete, Daniel, Catarina, Professor Albertino, Professora Marques e Professora Abranches, tanto pelas forças de apoio moral e psicológico, pelas recomendações e conselhos de vida, e principalmente pela amizade e memórias ao longo desta batalha. Por último, mas não menos importante, quero agradecer a incessante confiança, companhia e aceitação do bom e do mau pela minha Twin, Safira, que nunca me abandonou em todo o processo desta investigação, do meu caminho académico e da conquista da vida e sonhos. -

Dungeon Crawl Classics #63: the Warbringer's

TABLE OF CONTENTS Official Tournament Results ......................................................................8 Introduction ........................................................................................................9 Adventure Summary ...........................................................................................9 Game Masters Section .....................................................................................10 Round One: Background Story .................................................................11 Round One Encounter Table ......................................................................11 Player Beginning ................................................................................................13 Round Two: Consulting the Oracle ......................................................35 Round Two Encounter Table .....................................................................35 Player Beginning ................................................................................................35 Round Three: The Island Shrine ..............................................................60 Round Three Encounter Table ..................................................................61 Player Beginning ...............................................................................................62 Appendix A: New Monsters.............................................................................78 Appendix B: New Items ......................................................................................79