Valuation of Salmar ASA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Equinor Pensjon Årsberetning Og Regnskap Annual Report and Accounts

2018 Equinor pensjon Årsberetning og regnskap Annual report and accounts EQUINOR PENSJON - 2018 ÅRSRAPPORT 1 NØKKELTALL BELØP I MILLIONER KR 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 Premieinntekter 1 864 1 688 1 289 2 445 3 060 Pensjonsutbetalinger 1 256 1 143 1 031 903 778 Totalresultat 215 729 348 291 543 Forvaltningskapital 67 346 69 623 65 103 66 746 65 964 Egenkapital 7 623 7 408 6 679 6 331 6 040 Verdijustert avkastning -1,8 % 7,8 % 3,7 % 4,3 % 7,6 % Antall pensjonister* 4 409 4 217 4 164 3 829 3 507 Aktive medlemmer * 4 589 4 992 5 102 5 797 19 515 Antall personer med fripoliser * 24 753 24 792 24 230 23 917 5 734 * Ansatte som hadde mer enn 15 år igjen til pensjonsalder ble 1.4.2015 overført til den nye innskuddspensjonsordningen. Det ble i forbindelse med overgangen utstedt fripoliser for opptjente rettigheter til ca 13.000 medlemmer. Pensjonsutbetalinger pr. kategori Aktive medlemmer mill NOK 1 200 20 000 1 000 15 000 800 600 10 000 400 5 000 200 0 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Alder Uføre Ektefelle Barn STYRE OG ADMINISTRASJON Styre Styret består av åtte representanter, alle med personlig vara. Fire av representantene er utnevnt av medlemsbedriftene, tre av representantene er valgt av medlemmene og i tillegg er det en uavhengig representant. Medlemsbedriftenes Uavhengig representanter: representant: Hans Henrik Klouman, Ove Christian Norheim 1 styrets leder Geir Johan Husøy Daglig leder Siv Solem Solveig Åsland Marit Lunde 3 4 Medlemmenes representanter: Stig Erling Sandvik Oddvar Karlsen Jorunn Birkeland Medlembedriftene Uavhengige Medlemmene Nøkkeltall 3 Aktuarberetning 33 Styre og administrasjon 3 Revisjonsberetning 34 Styrets årsberetning 4 English version 37 Årsregnskap 7 INNHOLD EQUINOR PENSJON - 2018 ÅRSRAPPORT 3 STYRETS ÅRSBERETNING 2018 Om virksomheten som godt forberedt til å møte det nye kravet. -

Plain Language in the Norwegian Financial Services

Plain Language Association International’s 11th conference Improving Customer Relationships September 21-23, 2017 University of Graz, Austria hosted by Klarsprache.at Copyright of this presentation belongs to the presenter www.plainlanguagenetwork.org Plain Language in the Norwegian financial sector Graz, 22nd September 2017 Gry Nergård, Consumer Policy Director www.finansnorge.no Introduction • Gry Nergård • Lawyer • Consumer Policy Director, Finance Norway • Former Norwegian Consumer Ombudsman www.finansnorge.no 3 Our members: • Finance Norway is the industry • Savings banks organisation for the financial • Commercial banks industry in Norway. • Life insurers • We represent about 240 financial • Non-life insurers companies with around 50,000 • Savings bank foundations employees. • Mortgage companies • Financial conglomerates • Other financial companies www.finansnorge.no Changes in the retirement pension system www.finansnorge.no The P-word www.finansnorge.no What is difficult? • Summer 2016: questionaire to 1000 consumers • Confirmed: • Economical terms are incomprehensible to most people. • In plain language: they are totaly not understandable! www.finansnorge.no Finance Norway’s Plain Language Project Main goals • Better information to consumers about retirement pension • Better choices – better pensions • Reduce capasity and costs in costumer relations • Better language culture in the companies • Reputation and trust www.finansnorge.no Working methode • Steering group • Working grpup • Bilateral cooperation between each company -

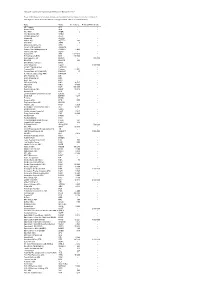

Asset Listing for the New York State Common Retirement Fund As Of

New York State Common Retirement Fund Asset Listing as of March 31, 2017 Domestic and International Equity 1 - 62 Commingled Stock Funds 63 Global Fixed Income 64 - 84 Mortgage Holdings 85 - 89 Real Estate Investments 90 - 92 Short-Term Investments 93 - 94 Alternative Investments Assets: Private Equity Investments 95 - 99 Private Equity Investments / Fund of Funds Listing 100 - 109 Absolute Return Strategy / Fund of Funds Listing 110 Opportunistic Funds 111 Real Assets 112 DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL EQUITY As of March 31, 2017 Security Description Shares Cost Fair Value 180 Degree Capital Corp. 960,396 $1,986,291 $1,392,574 1-800-Flowers.com, Inc. - Class A 22,800 222,660 232,560 1st Source Corp. 21,434 657,207 1,006,326 2U, Inc. 43,925 1,368,977 1,742,065 3D Systems Corp. 110,800 1,434,860 1,657,568 3M Company 1,705,000 120,381,155 326,217,650 77 Bank, Ltd./The 280,000 1,266,651 1,211,164 888 Holdings plc 30,937 103,808 103,289 8X8, Inc. 329,016 3,456,968 5,017,494 A10 Networks, Inc. 37,100 224,604 339,465 AA, Ltd. 2,603,082 11,942,240 8,645,343 AAC Holdings, Inc. 9,300 340,886 79,329 AAC Technologies Holdings, Inc. 1,578,900 13,719,169 18,477,894 AAON, Inc. 42,500 647,616 1,502,375 AAR Corp. 35,200 872,406 1,183,776 Aarons, Inc. - Class A 632,650 16,352,050 18,815,011 Abaxis, Inc. -

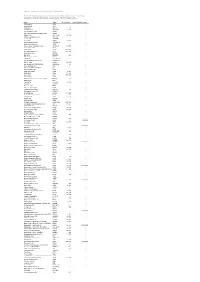

Positions in Financial Instruments As of February 2Nd 2017

Disclosure - positions in financial instruments as of February 2nd 2017 Please find below a list of positions in financial instruments held by employees of Arctic Securities AS with regard to Arctic Securities' research coverage universe. The list is updated monthly. Name Ticker No of shares Nominal NOK in bonds AF Gruppen AFG - - Akastor ASA AKA - - Aker ASA AKER 2 - Aker Solutions ASA AKSO - - Alcadon Group AB ALCA Aligera AB ALIRAB - - Asetek A/S ASETEK 291 - Atea ASA ATEA 3 - Atwood Oceanics, Inc. ATW - - Aurora LPG Holdings AURLPG - - Avance Gas Holdings Limited AVANCE 6 445 - Awilco LNG ASA ALNG - - Axactor AB AXA 1 027 846 - B2Holding AS (B2H) B2H 215 500 - Bulk Industrier AS BUIN01 - 500 000 BW LPG BWLPG 223 - BW Offshore Limited BWO - - Color Group AS COLG - 3 000 000 Corem Property Group CORE SS - - Cxense ASA Cxense 21 552 - Danske Bank A/S (DANSKE) DANSKE 27 - Det Norske Oljeselskap ASA DETNOR - - DHT Holdings, Inc. DHT - - Diana Shipping Inc DSX - - DistIT AB DIST - - DNB ASA (DNB) DNB 10 727 - DNO ASA DNO 17 500 - DOF ASA DOF 500 000 - Dolphin Group ASA DOLP 56 616 - Dorian LPG LPG - - Electromagnetic Geoservices ASA EMGS 15 - Entra ASA ENTRA 4 268 - Euronav EURN - - Europris ASA EPR 2 900 - Fingerprint Cards AB FING-B - - Frontline Ltd. FRO 5 050 - Gjensidige Forsikring ASA (GJF) GJF 12 787 - Golar LNG Ltd GLNG - - Golden Ocean Group Ltd. GOGL 7 027 - Grieg Seafood ASA GSF 18 000 - Havfisk ASA HFISK - - Havila Shipping HAVI - - Helgeland Sparebank (HELG) HELG 557 - Höegh LNG Holdings HLNG 538 - IB Bostad 18 AB IB BOSTAD - 500 000 Idex ASA IDEX 65 685 - Jinhui Shipping and Transportation Ltd. -

Valuation of Grieg Seafood ASA

Valuation of Grieg Seafood ASA Authors: Fabian Løke & Sondre Teige Supervisor: Edward Vali Master thesis, Copenhagen Business School, 15th of May 2018 Student nr: 106077 & 107534 Word count: 35,009 Characters: 219,870 Pages: 118 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (BUY) Key data 19.04.2018 Price (NOK) 86.00 Improved capacity utilization in 2018 Target price (NOK) 104,59 Grieg Seafood is equipping for organic growth with Upside 20% investments in surveillance technology and smolt facilities. These investments are essential to increase harvest volume NOK (000) and reduce costs. Investment in surveillance and monitoring Ticker OSE GSF Shares outstanding 111.662 technology seems to yield results as sea-lice levels decreases Market cap 9.602.932 in earlier troubled regions. One of the expected contributors NIBD 1.790.101 to the future EBIDTA margin is Grieg Seafood’s Credit rating BBB 500 improvement in operational efficiency. Share performance 400 Supply and demand 300 In the short term-supply is expected to grow as both smolt 200 release and standing biomasses are higher y-o-y. Increased 100 supply can expect to be met by a growing demand as health 0 trends and increased demand from European consumers are expected to strengthen demand. GSF OSEBX OBSFX Salmon price In the short-term we see salmon prices to remain above Target price estimates NOK 60 per kg. The company’s high exposure to the spot Danske Bank 110 market will be beneficial for the company as its sensitivity to Pareto 100 the spot price remain high. We see the salmon price to Nordea 100 stabilize close to NOK 60 per kg as supply and demand DNB 90 stabilizes. -

2019 Equinor Pensjon Årsberetning Og Regnskap Annual Report and Accounts

2019 Equinor Pensjon Årsberetning og regnskap Annual report and accounts EQUINOR PENSJON - 2019 ÅRSRAPPORT 1 NØKKELTALL BELØP I MILLIONER KR 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 Premieinntekter 2 053 1 864 1 688 1 289 2 445 Pensjonsutbetalinger 1384 1 256 1 143 1 031 903 Totalresultat 698 215 729 348 291 Forvaltningskapital 73 546 67 346 69 623 65 103 66 746 Egenkapital 8 320 7 623 7 408 6 679 6 331 Verdijustert avkastning 10,2 % -1,8 % 7,8 % 3,7 % 4,3 % Antall pensjonister* 4 630 4 409 4 217 4 164 3 829 Aktive medlemmer * 4 266 4 589 4 992 5 102 5 797 Antall personer med fripoliser * 24 731 24 753 24 792 24 230 23 917 * Ansatte som hadde mer enn 15 år igjen til pensjonsalder ble 1.4.2015 overført til den nye innskuddspensjonsordningen. Det ble i forbindelse med overgangen utstedt fripoliser for opptjente rettigheter til ca 13.000 medlemmer. Prinsippet for telling er endret. Pensjonsutbetalinger pr. kategori Aktive medlemmer mill NOK 1 400 8 000 1 200 6 000 1 000 800 4 000 600 400 2 000 200 0 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Alder Uføre Ektefelle Barn STYRE OG ADMINISTRASJON Styre Styret består av 8 representanter, alle med personlig vara. 4 av representantene er utnevnt av medlemsbedriftene, 3 av representantene er valgt av medlemmene og i tillegg er det 1 uavhengig representant. Medlemsbedriftenes Uavhengig representanter: representant: Hans Henrik Klouman, Ove Christian Norheim 1 styrets leder Geir Johan Husøy Daglig leder Siv Solem Solveig Åsland Marit Lunde 3 4 Medlemmenes representanter: Stig Erling Sandvik Oddvar Karlsen Jorunn Birkeland Medlembedriftene Uavhengige Medlemmene Nøkkeltall 3 Årsregnskap 7 Styre og administrasjon 3 Revisjonsberetning 36 Styrets årsberetning 4 English version 39 INNHOLD EQUINOR PENSJON - 2019 ÅRSRAPPORT 3 STYRETS ÅRSBERETNING 2019 Om virksomheten tilpasset til det nye kravet. -

Equinor Insurance AS Årsberetning Og Regnskap Annual Report and Accounts

2018 Equinor Insurance AS Årsberetning og regnskap Annual report and accounts EQUINOR FORSIKRING - 2018 ÅRSRAPPORT 1 2 EQUINOR FORSIKRING - 2018 ÅRSRAPPORT STYRETS ÅRSBERETNING 2018 Styret Forretningsfører Russell Alton, styreleder Lars Gaute Østebø Marit Lunde Anne-Margrethe Tostrup Smith Revisjon Mads Rømer Holm KPMG AS Lars Atle Kjøde Statsaut. revisorer Equinor Insurance AS. er et heleid datterselskap geografi og ulike verdipapirer. Equinor Insurance AS av Equinor ASA, lokalisert i Stavanger. Selskapet benytter også finansielle instrumenter (derivater) i er engasjert i skadeforsikring og bærer i det stedet for underliggende papirer (aksjer, obligasjoner vesentligste risiko for tingskade, avbruddstap og og sertifikater) hvis dette er mer hensiktsmessig og tredjemannsansvar i tilknytning til Equinorkonsernets kostnadseffektivt. Selskapet følger etiske retningslinjer virksomhet. for forvaltningen. Selskapet har ingen ansatte, men kjøper tjenester I forbindelse med endring i porteføljesammensetning fra morselskapet og av Gabler Triton. Styrets brukes det tidvis også børsnoterte futureskontrakter sammensetning ved årsslutt består av to kvinner og tre på aksjeindekser. Innenfor renteområdet brukes menn. rentefutures, fremtidige renteavtaler, rentebytteavtaler, gjenkjøpsavtaler og renteopsjoner for å forvalte Styret er ikke kjent med at selskapets virksomhet hensiktsmessig og kostnadseffektivt. I forbindelse med gjennom året har medført forurensing av det ytre miljø. styring av valutarisiko benyttes valutaswapper og valutaterminer. Styret -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 www.bakkafrost.com Faroese Company Registration No. 1724 BAKKAFROST 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Table of Contents Chairman’s Statement 4 PERFORMANCE 32 Statement by the Management Operational Review 33 and the Board of Directors 6 Financial Review 36 Who Are We? 8 Farming Segment 38 Key Figures 10 VAP Segment 40 Main Events 12 FOF Segment 42 Outlook 14 Business Review 46 STRATEGY 17 RISK 61 Business Objectives and Strategy 18 Risk and Risk Management 62 Business Model 19 Bakkafrost’s History 22 GOVERNANCE 67 The Value Chain 24 Corporate Governance 68 Group Structure 29 Health, Safety and the Environment 70 Operation Sites 30 Shareholder Information 72 Directors’ Profiles 73 Group Management’s Profiles 76 Other Managers’ Profiles 78 Statement by the Management and the Board of Directors on the Annual Report 80 Independent Auditor’s Report 81 BAKKAFROST 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CONTENS STATEMENTS AND NOTES 86 P/F BAKKAFROST - TABLE OF CONTENTS 144 Consolidated Income Statement 88 P/F BAKKAFROST - Income Statement 145 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 89 P/F BAKKAFROST - Statement of Financial Position 146 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 90 P/F BAKKAFROST - Statement of Financial Position 147 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 91 P/F BAKKAFROST - Cash Flow Statement 148 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 92 P/F BAKKAFROST - Statement of Changes in Equity 149 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 93 P/F BAKKAFROST - Notes to the Financial Statements 151 NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED APPENDIX 158 -

Monthly Report June 2021

Pareto Aksje Norge I Report date: 31 August 2021 Fund: Pareto Aksje Norge Category: equity fund Unit class I Inception date: 6 September 2001 Legal structure: UCITS NAV as at 31 Aug 2021: 10 725.48 Minimum investment: NOK 100 000 000 AUM: NOK 6.4 billion Domicile: Norway NAV currency: NOK ISIN: NO0010110968 Benchmark: Oslo Børs Mutual Fund Index Dealing days: all Norwegian business days Launch date: 6 September 2001 Bloomberg ticker: POAKTIV NO Norwegian equity fund focused on sectors where Investment criteria: Norwegian companies have global competitive . Sound balance sheets advantages . Strong historical returns on equity . Reasonable pricing Top ten holdings and sector allocation Lerøy Seafood Group ASA 8.8% Financials 24% Yara International ASA 8.2% SpareBank 1 SMN 5.6% Materials 22% Wilh. Wilhelmsen Holding ASA 5.4% Consumer staples 19% SpareBank 1 SR-Bank ASA 5.0% Industrials 16% Borregaard ASA 4.7% Energy 13% SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge 4.7% Elkem ASA 4.5% Consumer discretionary 5% SalMar ASA 4.5% Cash 0% Kid ASA 4.4% Key figures since inception* Risk figures since inception* Performance by periods Fund Index Fund Index Fund Index Accumulated returns973 % 547 % Standard deviation (annualised) 19.3% 21.0%Last month 0.6% 0.3% Annualised returns12.6 % 9.8 % Tracking error (annualised) 8.9% n.a.Year to date 19.8% 16.9% Information ratio 0.3 n.a.Last 12 months 38.6% 33.9% Sharpe ratio (SOL1X)** 0.5 0.35Three years (annualised) 8.1% 9.8% Beta 0.8 n.a.Five years (annualised) 15.2% 13.4% Ten years (annualised) 10.3% 12.1% **ST1X was used until -

2020 Equinor Pensjon Årsberetning Og Regnskap Annual Report and Accounts

2020 Equinor Pensjon Årsberetning og regnskap Annual report and accounts EQUINOR PENSJON - 2020 ÅRSRAPPORT 1 NØKKELTALL BELØP I MILLIONER KR 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 Premieinntekter 1 457 2 053 1 864 1 688 1 289 Pensjonsutbetalinger 1 478 1 384 1 256 1 143 1 031 Totalresultat 832 698 215 729 348 Forvaltningskapital 78 609 73 546 67 346 69 623 65 103 Egenkapital 9 152 8 320 7 623 7 408 6 679 Verdijustert avkastning 7,8 % 10,2 % -1,8 % 7,8 % 3,7 % Antall pensjonister* 4 939 4 630 4 409 4 217 4 164 Aktive medlemmer * 3 881 4 266 4 589 4 992 5 102 Antall personer med fripoliser * 24 634 24 731 24 753 24 792 24 230 * Ansatte som hadde mer enn 15 år igjen til pensjonsalder ble 1.4.2015 overført til den nye innskuddspensjonsordningen. Det ble i forbindelse med overgangen utstedt fripoliser for opptjente rettigheter til ca 13.000 medlemmer. Pensjonsutbetalinger pr. kategori Aktive medlemmer mill NOK 1 600 6 000 1 400 5 000 1 200 4 000 1 000 800 3 000 600 2 000 400 200 1 000 0 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Alder Uføre Ektefelle Barn STYRE OG ADMINISTRASJON Styre Styret består av 8 representanter, alle med personlig vara. 4 av representantene er utnevnt av medlemsbedriftene, 3 av representantene er valgt av medlemmene og i tillegg er det 1 uavhengig representant. Medlemsbedriftenes Uavhengig representanter: representant: Hans Henrik Klouman, Ove Christian Norheim 1 styrets leder Geir Johan Husøy Daglig leder Siv Solem Solveig Åsland Marit Lunde 3 4 Medlemmenes representanter: Stig Erling Sandvik Oddvar Karlsen Jorunn Birkeland Medlembedriftene Uavhengige Medlemmene Nøkkeltall 3 Årsregnskap 8 Styre og administrasjon 3 Revisjonsberetning 37 Styrets årsberetning 4 English version 39 INNHOLD EQUINOR PENSJON - 2020 ÅRSRAPPORT 3 STYRETS ÅRSBERETNING 2020 Om virksomheten forventninger til styring og kontroll. -

Stoxx® Europe Ex Eurozone Total Market Small Index

SIZE INDICES 1 STOXX® EUROPE EX EUROZONE TOTAL MARKET SMALL INDEX Stated objective Key facts STOXX calculates several ex region, ex country and ex sector indices. This means that from the main index a specific region, country or sector is excluded. The sector classification is based on ICB Classification (www.icbenchmark.com.)Some examples: a) Blue-chip ex sector: the EURO STOXX 50 ex Financial Indexexcludes all companies assigned to the ICB code 8000 b) Benchmark ex region: the STOXX Global 1800 ex Europe Index excludes all companies from Europe c) Benchmark ex country: the STOXX Europe 600 ex UK Index excludes companies from the United Kingdom d) Size ex sector: the STOXX Europe Large 200 ex Banks Index excludes all companies assigned to the ICB code 8300 Descriptive statistics Index Market cap (USD bn.) Components (USD bn.) Component weight (%) Turnover (%) Full Free-float Mean Median Largest Smallest Largest Smallest Last 12 months STOXX Europe ex Eurozone Total Market Small Index 571.4 470.4 1.8 1.6 5.8 0.2 1.2 0.0 11.9 STOXX Europe ex Eurozone Total Market Index 6,336.8 5,463.3 10.8 2.9 250.9 0.2 4.6 0.0 2.3 Supersector weighting (top 10) Country weighting Risk and return figures1 Index returns Return (%) Annualized return (%) Last month YTD 1Y 3Y 5Y Last month YTD 1Y 3Y 5Y STOXX Europe ex Eurozone Total Market Small Index 0.8 1.4 20.3 71.4 122.0 9.9 2.0 19.8 19.1 16.8 STOXX Europe ex Eurozone Total Market Index 0.8 4.7 18.7 50.7 82.7 9.8 7.0 18.3 14.3 12.4 Index volatility and risk Annualized volatility (%) Annualized Sharpe ratio2 -

Positions in Financial Instruments As of July 10Th 2017

Disclosure - positions in financial instruments as of July 10th 2017 Please find below a list of positions in financial instruments held by employees of Arctic Securities AS with regard to Arctic Securities' research coverage universe. The list is updated monthly. Name Ticker No of shares Nominal NOK in bonds AF Gruppen AFG - - Akastor ASA AKA - - Aker ASA AKER 2 - Aker BP ASA AKERBP 1 500 - Aker Solutions ASA AKSO - - American Shipping Company ASA AMSC - - Archer Ltd. ARCHER 33 400 - Ardmore Shipping Corp. ASC US - - Asetek A/S ASETEK - - Atea ASA ATEA 2 803 - Atlantic Sapphire AS ATLANTIC - - Atwood Oceanics, Inc. ATW - - Avance Gas Holdings Limited AVANCE 24 045 - Awilco LNG ASA ALNG - - Axactor AB AXA 877 846 - B2Holding AS (B2H) B2H 242 500 - BerGenBio ASA BGBIO - - BW LPG BWLPG 223 - BW Offshore Limited BWO - - Cherry AB CHER.B-SE - - Corem Property Group AB CORE SS - - Cxense ASA Cxense 20 332 - Danske Bank A/S (DANSKE) DANSKE 27 - DHT Holdings, Inc. DHT - - Diamond Offshore Drilling DO - - Diana Shipping Inc DSX - - DNB ASA (DNB) DNB 8 907 - DNO ASA DNO 17 500 - DOF ASA DOF 500 000 - Dorian LPG LPG - - Electromagnetic Geoservices ASA EMGS 15 - ENSCO plc ESV - - Entra ASA ENTRA 3 878 - Euronav EURN - - Europris ASA EPR - - Faroe Petroleum plc FPM - - Fastighets AB Balder BALDB 85 - Fingerprint Cards AB FING-B - - Flex LNG Ltd FLNG 19 000 - Fred. Olsen Energy ASA FOE 100 - Frontline Ltd. FRO 5 550 - Gaslog Ltd. GLOG - - Genmab A/S GEN - - Gentian Diagnostics GENT-ME 214 195 - Gjensidige Forsikring ASA (GJF) GJF 12 537 - Golar LNG Ltd GLNG - - Golden Ocean Group Ltd.